https://goo.gl/fkKyNj

Our Kickstarter campaign ends very soon.

This might be your last chance to get the game:)

And if you participated already, thanks, and we are looking forward to the next steps.

Dan

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

We recently invited two couples to spend the weekend with us at our cabin. We have two guest bedrooms, one larger and more comfortable than the other. When the first couple showed up, we suggested that they wait until the other couple arrived to discuss who would get which room or perhaps to toss a coin. But the first couple said that, since they had arrived first, they deserved the better room. I disagreed but didn’t want to argue, so they ended up taking the larger bedroom. Were they right to argue that taking the better room was fair?

—Shimon

The first couple demonstrated what’s commonly known as “motivated reasoning.” There are many possible rules of fairness: first-come-first-served, weighing needs, flipping a coin and so on. For self-serving reasons, this couple adopted the first-come-first-served approach, and instead of simply admitting that they wanted the larger room, they justified their selfishness by advocating a fairness rule that happened to lead to their preferred outcome.

But you didn’t announce the first-come-first-served rule in advance, so it isn’t fair to use it: The other couple didn’t know that they were in a competition. Because both couples are your friends, I wouldn’t have used any fairness rule that depended on human judgment about who’s more deserving. Better just to toss a coin. Next time, it would be better to announce in advance the fairness rule that you want to use.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been struggling recently to understand why childbirth is so painful. In principle, I suspect, nature could have made childbirth painless—so why did it “choose” to make it agonizing? Your research shows that the more labor we put into things, the more we love them. Could that explain why nature choose this approach—simply to make mothers value their children more?

—Tom

I’ll leave the evolutionary biology to others, but my research group’s findings are indeed consistent with your interpretation: The more one is involved with creating something and the more difficult and complex the task, the more we end up loving it. We call this the IKEA effect, because of people’s increased pride in furniture they’ve put together from a kit. But Mother Nature seems not to have fully read our work: We found that just a bit of involvement would achieve the IKEA effect, so much less pain at childbirth would have sufficed.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My son just turned 13, and he and his friends are starting to dare each other to do all kinds of stupid things. Some dares involve eating very spicy or disgusting foods; others involve jumping from high places; some involve asking girls out. I don’t get it. Why would someone suddenly be willing to do something just because the word “dare” is invoked?

—Manny

Let’s consider two different types of dare. The first type is meant to help the person carrying it out. Imagine, for example, that your son has a crush on a girl but is too shy to tell her. If his friends dared him to ask her out, the social embarrassment would decline, and your son might be prodded into getting a fun date.

But there is a second type of dare—for instance, goading someone to eat jalapeño peppers or to jump off a wall. This category isn’t about the immediate well-being of the person doing the dare; it is about his or her place in a social hierarchy. The more impressive the dare, the higher their social status rises.

I hope that this helps you to see some of the beauty of dares—and maybe even to try out a double-dare yourself.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

On a recent trip, the car-rental agency offered me insurance that cost almost as much as the rental itself. I ended up taking it, but when I got the credit-card bill, I couldn’t understand what I’d been thinking. Why do we buy these things?

—Benjamin

It has to do with counterfactual thinking and regret. Imagine that you take the same route home from work every day. One day, along the usual route, a tree falls and totals your car. Naturally, you’d feel bad about the loss of the car—but you’d feel much worse if, on that particular day, you had tried a shortcut and, with the same bad luck, come across the car-wrecking tree. In the first case, you’d be upset, but in the shortcut case, you’d also feel regret about taking that different route.

The same principle applies to car rentals. When a rental agent offers us pricey insurance, we start imagining how stupid and regretful we’d feel if we skipped it and (God forbid) had an accident. Our desire to avoid feeling this way makes us much more interested in the insurance.

Now, it probably is OK to pay a bit more to avoid remorse from time to time—but when the price tag gets large, we should start looking for ways to cope more directly with our feelings of regret.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m wondering what you make of gun control. Obviously, it is in everyone’s best interest to have a safer country where you’re less likely to be shot in public. But since the massacre in Oregon, gun sales have only gone up. Is there anything we can do to reduce gun violence?

—Skyler

This all strikes me as a case of over-optimism. When we hear about gun violence, we tell ourselves, “If I didn’t have a gun, I might get attacked—but if I had a gun, I could protect myself.” We can imagine the benefits of gun ownership, but we can’t imagine the stress or panic we’d feel while being attacked. (In wartime, in fact, many guns never get fired because of the stress felt by people under fire.) We also can’t imagine ourselves as hotheaded attackers or imagine our new gun being used by people in our household to attack others.

After all, we’re such good, reasonable people, and those surrounding us are similarly upstanding and calm. So people buy guns, often with good intentions—but these guns make it easy for someone having a moment of anger, hate or weakness to do something truly devastating.

Since humanity will keep having emotional outbursts, what can we do to lessen gun violence? One approach would be to try to make it less likely that we will make mistakes under the influence of emotions. When we set rules for driving, we’re very clear about when and how cars can be used, which involves heeding the speed limit, obeying traffic rules and so on. Maybe we should also set up strict rules for guns that will make it clear when and under what conditions guns can be carried and used. And we could require gun owners to get licenses and training—again, on the model of car safety—with penalties for breaking the rules.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When my chore-hating kids visit their friends, they clear their dishes and help in the kitchen. How can I get them to do that at home?

—Jon

Like many of us, kids are motivated by the impressions they make on people they care about. Clearly (and sadly), you aren’t on that list. Maybe you can get one of those home cameras, connect it to your kids’ Facebook feeds and observe the power of impression management as they try to impress their friends.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

You may have heard about the recent Volkswagen scandal involving a cheat to pass emissions tests in VW diesel vehicles.

I’d like to get your opinions about this event, so I’ve added a questionnaire to my survey app called “(sample) size matters.”

If you would like to participate in the study (as well as other studies that you’ll find in the app), simply download the app on iOS or Android and share your opinions.

Irrationally Yours,

Dan Ariely

The day has finally come!

We’ve just launched the Irrational Game Kickstarter campaign, which means you can now get the game and some other rewards here.

The Irrational Game – We hope it will be a thought provoking, engaging and fun way to incorporate social sciences and human behavior into a challenging and strategic game.

It should also give you a way to reflect on your behavior and what you might want to change

If you consider supporting the project, please do it on the first day. A first day boost will give us great momentum for the entire campaign!

Thank you so much for all of your support. We can’t wait to get you the game.

Irrationally yours,

Dan

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Recently, our babysitter asked to borrow my car—then had a minor accident that cost about $1,000 to fix. Should I charge her for the repairs?

—Neta

You shouldn’t, for two reasons. To view this problem through a more general mindset, let’s assume that the culprit wasn’t your babysitter and that the object in question wasn’t your car—instead, let’s imagine you’d loaned your neighbor your electric drill and it broke while he hanging a picture. He might offer to pay for the drill, but if he didn’t, would you ask him to pay for it? Probably not. You’d understand that wear and tear happens, that the breakage probably wasn’t your neighbor’s fault and that the drill would have broken anyway. In contrast, when someone has a car accident, we’re quick to blame them—but from time to time, accidents just happen through no fault of the driver’s. Maybe this is a good opportunity to accept the accident as part of wear and tear on the car.

Another reason why you shouldn’t ask the babysitter to pay: They’re your babysitter, and while they might be a very trustworthy teenager, you were the one who decided to lend them your car. Best to own up to that responsibility.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m planning to hire a professional clothing stylist to study my body type and style and advise me on which clothes to keep and which to give away. I’m considering two options: first, asking her to take all the clothes she doesn’t approve of out of my closet, and second, to first take everything out and then put back the things she thinks pass muster. Which approach would you recommend?

—Maria

You’re right to suspect that the two methods will probably result in different outcomes. The reason is the “status quo bias”—the tendency to leave things as they are. If you start with all the clothes in the closet, the effort required to keep items there is lower than the effort required to take them out, which means that fewer clothes will end up being given away. On the other hand, if you start with all your clothes out of the closet, the lower-effort course involves leaving clothes where they are, which means more things will end up being given away.

But you’re unlikely to apply the status quo bias evenly to your whole wardrobe: The clothes that are clearly great will probably stay with you regardless of your method, and the clothes that are just awful will probably be given away either way too. The difference will come from the “Goldilocks clothes”—the ones that rest somewhere between those two clear categories. The real question is how many of these Goldilocks clothes you want to keep.

Two more points: If you don’t fully trust the stylist, you might start with the “all clothes in” approach, take fewer risks and keep more of the Goldilocks clothes. Also, some clothes will have sentimental value even if someone else thinks they look awful on you – so keep these. After all, we dress for ourselves, not just for other people.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What is the best example of human irrationality?

—Bill

I must admit I’ve never understood why the most important medical center in the world, the Mayo Clinic, is conveniently located in balmy Rochester, Minn. I’ve benefited enormously from their care—but it’s a long trip.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My boyfriend and I recently broke up, and the anguish and depression have been hard to bear. How can I cope with the feeling that my life has come to a halt?

—Inbal

In general, when we experience a strong emotion—whether it is anger, joy or grief—we tend to believe that it will stay with us for a very long time. In fact, time dulls the sensation far faster than we expect. The end of a relationship can be a terribly difficult life event, but studies show that people expect the pain of a broken heart to last much longer than it actually does.

One way to make things easier on yourself, while the agony subsides, is to change as many of your life patterns as possible so that you don’t constantly run into painful reminders of your ex.

Go to different restaurants and meet new people. If you can, take a trip to a place you’ve never visited before.

Breakups are one of the great universal human experiences. I wish that I had a simple silver-bullet solution for the pain they cause, but I don’t.

Personally, I think that enduring a difficult separation is an experience that we can learn from—and a way to increase our chances for doing better the next time around.

Maybe it would help to look at the pain as a byproduct of learning.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

People today are far more aware of the dangers of obesity—we even hear about a public war on it. But we keep eating and eating. I certainly do, and I don’t know how to change. What’s our problem?

—Dror

We aren’t focusing on the right things. We’re fighting the obesity epidemic by providing people with education and nutritional information—based on the assumption that knowledge will encourage us to make better decisions. But that’s not how people behave.

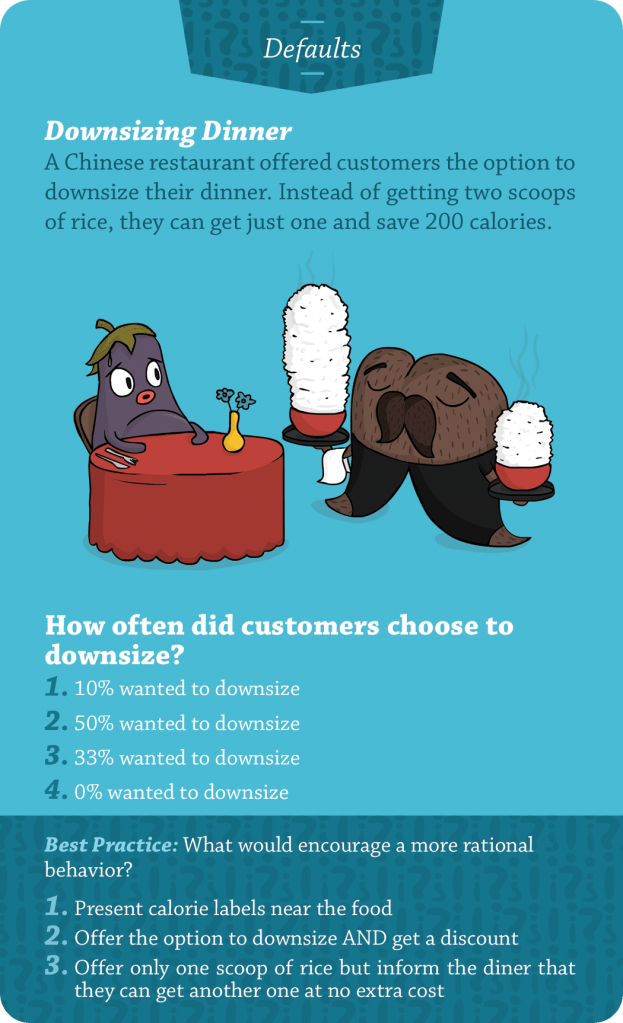

In an experiment led by my former Duke University colleague Janet Schwartz, our team went to a Chinese fast-food restaurant to try to see what effect providing nutritional information and calorie counts would have on diners. Some days, we placed that information next to each dish; other days we hid it.

The effect? Nothing. The knowledge that some dishes were much less healthy than others made no difference whatsoever on customers.

The British chef Jamie Oliver recently made a similar point. He showed children all the gross bird parts used to make their beloved chicken nuggets—bones, tendons, skin and worse—then ground the disgusting mix into a paste and fried it in breadcrumbs. When he took the nuggets out of the pan, the kids still all wanted to eat them.

If we forget what we’re eating so quickly, what hope does health education have?

The upshot, I’d argue, is that if we want to change eating behavior, we need to ditch the failed educational approach.

For example, instead of allowing people to buy a 64 oz. soda while providing them with calorie information that we hope will make them decide on a healthier option, why not simply limit the size from the start?

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Volkswagen recently admitted to cheating on emissions tests in its diesel-powered cars. What’s your take?

—Maya

As the owner of a VW Golf myself (not diesel), I’m deeply offended by the company’s emissions fixing, and I haven’t been able to look at my car in the same way since. Time will tell whether we can patch up our relationship.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently saw an episode of “How I Met Your Mother” in which one of the characters says, “Nothing good ever happens after 2 a.m.” I totally agree. But why? Does the dark make us misbehave, or is it something else? How can we stay safe and responsible in the wee hours?

—Aaron

You’re probably right that bad things are more likely to happen after 2 a.m. During the day, we face many temptations, and we overpower them with self-control.

But that control is like a muscle, and it gets tired from repeated use—not physical exhaustion but a mental fatigue that comes from making responsible, restrained choices over and over.

So when night falls, we can simply be too tired to keep being good and restrained—leaving us ready to fail.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m a high-school science teacher and a dean. We’ve had to discipline a number of students for cheating or plagiarism. Under our “two strikes and you’re out” policy, this puts them on the verge of getting kicked out of school after one infraction. The students were remorseful and confident that they would never again find themselves ripping off documents or copying papers—but then many of them cheated again. How can we better equip them to avoid such pitfalls?

—Morgan

It turns out that the fear of being caught doesn’t do much to deter crime in general. Even states that have the death penalty don’t report any noticeable difference in crime rates compared with those that don’t, according to a 2012 report by the National Research Council of the National Academies.

California’s “three strikes and you’re out” law was designed to take repeat criminals off the streets and deter offenders from repeated crimes. The theory was that if you knew that a third strike carried an especially harsh penalty, you would be deterred from further crimes.

But “three strikes and you’re out” didn’t seem to have a big effect on crime rates, according to a March 2000 study by James Austin and colleagues. And if “three strikes” didn’t work for crime, it’s unlikely to work for academic misdeeds.

We need to look for more effective approaches. Ultimately, what often stops us isn’t the fear of punishment but our own sense of right and wrong.

So you need to develop your students’ moral compasses. Maybe you should spend as much time on ethics as you do on math and history. After all, when they leave school, they’ll start applying their morals (whatever they are) to the world we share.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

On a recent business trip to San Francisco, I showed up early for a meeting, so I went to wait in a coffee shop. A cup of coffee was $8, and it was full of young people. Don’t they have anything better to do with their money? Don’t they have jobs? Don’t they find it morally reprehensible to spend more than the hourly minimum wage on a cup of coffee?

—Maria

I feel the same way. Still, it is all relative: If the liquid in question was wine, at just $8 a glass, we might not feel so offended. Maybe we need to be a bit less prejudiced against coffee.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like