Avoiding Typing – An App for That!

I have a hard time typing because of my injuries. I have tried all kinds of things over the last few years. I asked Ray to help me by writing a piece of software that helps me to record voice notes and send them over e-mail – Either as original e-mail, or as responses to e-mail.

I find it incredible useful! It’s called Vail and we just made the software available online. Note that it only works for Apple Mail on a Mac.

If you want to see it in action, look at the video in this link. Instructions for how to download the software are in the notes under the video. I hope you will find it as useful as I do.

Discussing Irrationality on the C20 Podcast

Ask Ariely: On Deconstructing Dieting, Advising Advantages, and Judging Jokes

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My diet goal is to stop eating so many sweets and start eating more vegetables. Would it be easier for me to focus on avoiding what I don’t want to eat or on eating more of what I should?

—Charlotte

Whether you focus on the positive goal or the negative one, the key thing to keep in mind is what social scientists call the principle of “friction”: People tend to follow the course of action that requires the least effort.

What this means is that you should arrange your environment to make it easier to achieve your goals. Place vegetables in a visible spot in your refrigerator and make sure that you serve them first at mealtimes, so you will have to expend minimal effort to eat them. Do the opposite with sweets—place them out of sight or on the highest shelf in the pantry, making them harder to reach.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

At my company, management is encouraging employees to seek advice and feedback from one another to improve our performance. But in my experience, it’s really hard to get people to give you useful, honest feedback, because they are afraid of giving offense. Is there any way to make this process work, or is it going to be a waste of time?

—Patricia

You’re right that people are unlikely to give accurate and honest feedback to their co-workers; there is a lot of social pressure against offering criticism, and people who receive it are likely to take offense.

But while it’s often hard to change our behavior in response to feedback, it turns out that giving advice can be more useful than receiving it. A recent study published in the journal Psychological Science shows that people who gave advice were more motivated when it came to challenges like controlling their tempers, saving money and finding jobs. In a follow-up study, high-school students who gave advice earned higher grades than those who received it.

This research suggests that giving advice can be a powerful confidence-booster—so your company’s initiative might be useful overall, even if people don’t act on the advice they receive.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve noticed that jokes that are meant to be funny sometimes come across as painful or offensive. Is there a way to know whether a joke is going to hurt people’s feelings?

—Pete

According to the behavioral scientist Peter McGraw of the University of Colorado, Boulder, jokes are funny when they involve “benign violations”: They transgress a social norm but not so much that they become objectionable. The trick is to hit the sweet spot between amusing and offensive.

For example, The Onion recently ran the headline “Harvard Officials Say $8.9 Million Donation From Jeffrey Epstein Was From Brief Recovery Period When He Wasn’t A Pedophile.” When I asked my friends how funny they found this headline, the ones from Harvard found it much less funny.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Cutting Cola, Loving Labor, and Engaging Investments

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been drinking soda for the past 15 years, and I’m trying to stop. I’ve tried phasing it out by switching to water some of the time and having a soda here and there, but I usually cave in to temptation by the end of the day. Is there a better strategy?

—Andrew

Getting off soda gradually isn’t going to be easy. Every time you resist having one, you expend some of your willpower. If you’re asking yourself whether you should have a soda whenever you’re thirsty, you’ll probably give in a lot and gulp one down.

So how can you break a habit without exposing yourself to so much temptation and depending on constant self-control to save you? Reuven Dar of Tel Aviv University and his colleagues did a clever study on this question in 2005. They compared the craving for cigarettes of Orthodox Jewish smokers on weekdays with their craving on the Sabbath, when religious law forbids them to start fires or smoke.

Intriguingly, their irritability and yearning for a smoke were lower on the Sabbath than during the week—seemingly because the demands of Sabbath observance were so ingrained that forgoing smoking felt meaningful. By contrast, not smoking on, say, Tuesday took much more willpower.

The lesson? Try making a concrete rule against drinking soda, and try to tie it to something you care deeply about—like your health or your family.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been living with a roommate for six months, and we divide up the household responsibilities pretty evenly, from paying the bills to grocery shopping. He says, however, that he feels taken for granted—that I don’t acknowledge his hard work. How can I fix this?

—C.J.

This is a pretty common problem. If you take married couples, put the spouses in separate rooms, and ask each of them what percentage of the total family work they do, the answers you get almost always add up to more than 100%.

This isn’t just because we overestimate our own efforts. It’s also because we don’t see the details of the work that the other person puts in. We tell ourselves, “I take out the trash, which is a complex task that requires expertise, finesse and an eye for detail. My spouse, on the other hand, just takes care of the bills, which is one relatively simple thing to do.”

The particulars of our own chores are clear to us, but we tend to view our partners’ labors only in terms of the outcomes. We discount their contributions because we understand them only superficially.

To deal with your roommate’s complaint, you could try changing roles from time to time to ensure that you both fully understand how much effort all the different chores entail. You also could try a simpler approach: Ask him to tell you more about everything he does for the household so that you can grasp all the components and better appreciate his work.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Is it useful to think about marriage as an investment?

—Aya

No, because the two things are profoundly different. You never want to fall in love with an investment because at some point you will want to get out of it. With a marriage, you hope never to get out of it and always to be in love.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Momentary Meaning, Hurried Health, and Poetic Practice

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why is it that the things that make me happy—such as watching basketball or going drinking—don’t give me a lasting feeling of contentment, while the things that feel deeply meaningful to me—such as my career or the book I’m writing—don’t give me much daily happiness? How should I divide my time between the things that make me happy and those that give me meaning?

—Vasini

Happiness comes in two varieties. The first is the simple type, when we get immediate pleasure from activities such as playing a sport, eating a good meal and so on. When you reflect on these things, you have no trouble telling yourself, “This was a good evening, and I’m happy.”

The second type of happiness is more complex and elusive. It comes from a feeling of fulfillment that might not be connected with daily happiness but is more lastingly gratifying. We experience it from such things as running a marathon, starting a new company, demonstrating for a righteous cause and so on.

Consider a marathon. An alien who arrived on Earth just in time to witness one might think, “These people are being tortured while everyone else watches. They must have done something terrible, and this is their punishment.” But we know better. Even if the individual moments of the race are painful, the overall experience can give people a more durable feeling of happiness, rooted in a sense of accomplishment, meaning and achievement.

The social psychologist Roy Baumeister and his colleagues distinguish between happiness and meaning. They see the first as satisfying our needs and wishes in the here-and-now, the latter as thinking beyond the present to express our deepest values and sense of self. Their research found, unsurprisingly, that pursuing meaning is often associated with increased stress and anxiety.

So be it. Simply pursuing the first type of happiness isn’t the way to live; we should aim to bring more of the second type of happiness into our lives, even if it won’t be as much fun every day.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently had my annual checkup, and my doctor spent maybe three minutes total with me during the visit. I know that physicians are busy, but are these quick visits the right way to go?

—James

Sadly, doctors increasingly feel pushed to move patients along as quickly as possible, like a production line. Research has shown that this approach hurts the doctor-patient relationship, which has important health implications.

Consider a 2014 study of patients who received electrical stimulation for chronic back pain, conducted by Jorge Fuentes of the University of Alberta and colleagues. They had medical professionals interact in one of two ways with their patients. Some were asked to keep their interactions short, while others were urged to ask deep questions, show empathy and speak supportively. Patients who received the rushed conversations reported higher levels of pain than those who got the deeper ones.

In other words, empathetic discussions are important for our health. Sadly, as physicians and other medical professionals become ever busier, we are shortchanging this vital part of healing.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Every year, my husband gets me a nice birthday card, but he never writes a personal note inside. Why?

—Ann

I suspect your husband overestimates the sentimental value of the words printed on the card, not realizing that they sound generic to you. Don’t judge him too harshly for this. Instead, buy one of those magnetic poetry sets and let him practice expressing himself on the fridge. Small steps.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Life (and the Pursuit of Happiness)– But for How Long?

Confronting our mortality is not an easy task for most people. However, there are many reasons people should consider just how long they might live.

In the case of retirement planning, life expectancy is important in relation to the benefits like Medicare and Social Security that people earn during their working years. According to the Pew Research Center, use of these government benefits programs is “virtually universal (97%) among those ages 65 and older—the age at which most adults qualify for Social Security and Medicare benefits.”

Differences in life expectancy between the rich and the poor can mean that more affluent Americans receive hundreds of thousands of dollars more in benefits that those who are less well off. In addition to the economic considerations, there is a psychological and perhaps even moral factor that comes into play when thinking about how long we might expect to live in relation to our financial status.

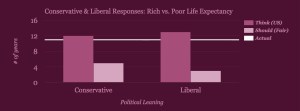

Topic 3 in Fair Game? asked users to think about exactly this question and to estimate how income is related to life expectancy and what that relationship should be in a fair world.

“It will surprise nobody to learn that life expectancy increases with income.”— Michael Specter, 4/16/16, The New Yorker

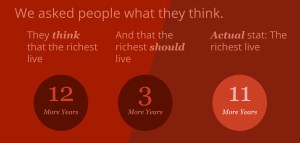

On the whole, our users estimated that the richest 10% of society would have a life expectancy 12 years longer than the poorest 10%. In reality, the difference is 11 years (12 additional years for men and 10.1 additional years for women).

How many more years of life do they think the wealthy should expect in a fair world? 3 more years (a 75% reduction from their estimate of what is true).

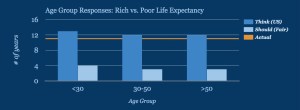

Estimates for the current difference in life expectancy were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair. Preferences for a fair difference were also similar. There may be hints of a difference between younger and older adults, with a possible explanation simply being ‘mortality salience’, or how much longer users themselves’ expect to live.

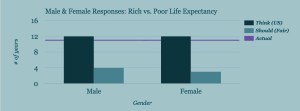

What about gender? Both males and females estimate 12 more years of life for the top 10%. But they differ slightly in what they think a fair amount of additional years would be — 4 vs. 3, respectively.

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal only differed by 1 year in terms of what they believed the life expectancy gain from wealth to be, and 2 years in what they thought it should be in a fair world. Conservatives estimate the gain to be 12 years, while liberals put it at 13 years. In terms of what they think would happen in a fair society, conservatives consider 5 years and liberals consider 3 years to be a fair number of years gained with wealth. Despite these small differences, the presumed improvement (from what is thought to what it should be) ends up being 7 years for conservatives vs. 10 years for liberals.

Together, the data reported here suggest that estimations of the present gap in life expectancy are fairly accurate. And that small differences in life expectancy (3-5 years) are considered fair (or perhaps tolerable) by most people. Has the wealth-based life expectancy gap always been this large? According to a Brookings report, it has actually grown from 4.5 years (for the cohort of seniors born in 1920) to 11 years (for the cohort born in 1940). It is likely that multiple factors, including differential access to quality medical care, and higher rates of smoking and obesity, contribute to the growth of this gap. On top of all of this, wealthier people typically retire later and can delay receiving social security payments, thereby increasing income inequality in the older population.

Unfortunately, public benefits that were originally intended to be progressive seem to be becoming (unintentionally) regressive over time. Perhaps there are some solutions that might help to keep more Americans living long, happy, and healthy lives?

What do you think? Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

Ask Ariely: On Ingesting Insects, Tracking Troubles, and Making Matches

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Many insects are edible, nutritious and even tasty, and they are consumed by millions of people world-wide. But when I try to eat one, I cannot get past the idea that bugs are, well, gross. Why?

—Zach

For many in the West, thinking about insects, not to mention eating one, evokes a powerful feeling of disgust. Psychologists often think about disgust as a sort of mental immune system, a deeply ingrained emotion that we have developed for evolutionary purposes to help us avoid pathogens, poisons and other pitfalls. You can even observe disgust in babies when they narrow their nostrils, constrict their lips and close their mouths while trying to expel or reduce contact with a potential contaminant.

So how could you get over your revulsion here? One option would be intensive immersion with insects. You could perhaps spend a week surrounded by pictures of them and then spend the next week locked in a room with nothing to eat but bugs.

Another less extreme option: Buy some insect powder and ask a friend to sprinkle it randomly into your meals, without your knowledge, and only tell you the next day which ones contained insects. Once you realize that the food still tasted good, your disgust should decrease.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that for many young adults, using a personal monitoring device may not help them lose weight. Should I stop using my Fitbit?

—Nati

When people start an exercise regimen, they often gain weight. The main reason: After we work out, we feel that we deserve a reward, such as a few scoops of ice cream. These extra calories can exceed those that we burn during our workout. I suspect that a similar phenomenon occurs when we wear tracking devices: We see that we’ve walked 10,000 steps or stood up 12 times during the day, and we feel justified in celebrating our amazing achievements. And of course, when we fail, we don’t feel that we need to deprive ourselves—so either way, it’s easy to wind up putting on pounds.

Still, you shouldn’t stop tracking your behavior. It is important to your health to understand when and how you become more or less active. Measurement can motivate you to become more active. And at the same time, you can work to discipline yourself not to expect a “reward” for hitting your daily targets.

You might also change the way that you measure success. What if, for example, you defined success not by making it to the gym on a particular day but by making it there on at least 80% of the days in a month—and only reward yourself when you clear that bar? If you move to such a system, I predict that tracking your health will work for you.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Like many of my friends, I love Tinder. The dating app provides a slideshow of potential romantic partners, and if two people “like” each other, Tinder tells them that they matched. How can such a simple app with so little information be so effective?

—Denise

When we think that we’re compatible with someone, we behave accordingly. A few years ago, the dating site OkCupid told users who had been rated only a 30% match for each other by the site’s algorithms that they were actually 90% matches—and these users ended up liking each other more. In Tinderland, when both people learn that they “like” one another, their expectations change, the match seems more appealing, and the power of self-fulfilling prophecy takes over.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Sanitation Solutions, Neighbor Needs, and Popular Politics

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I was recently at a barbecue restaurant where the toilets were private but the sinks were out in the open, in a common space. Would moving sinks to public areas get more people to wash their hands? Would you recommend this setup for all public bathrooms?

—Brian

Absolutely, and here’s why.

Sometimes, to show the extent of our irrationality, I will ask a large group, “In the past month, how many of you have eaten more than you think you should?” Almost everyone raises their hands. “In the past month, how many of you have exercised less than you think you should?” Again, everyone raises their hands. “In the past month, how many of you have texted while driving?” Almost everyone raises their hands.

Then I ask, “In the past month, how many of you have left the bathroom without washing your hands?” The result: almost perfect silence, no hands raised and, after a few embarrassed seconds, a bit of nervous laughter.

Obviously, they are lying—but why won’t people who have just confessed to something as reckless and stupid as texting while driving admit that they sometimes don’t wash their hands? I suspect that it is because we care pretty intensely about not being disgusting to others. As such, putting the sinks somewhere public and visible should encourage more hygienic behavior—ideally, with our friends and relatives watching over us to be extra-sure we do the right thing.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I hear the phrase “keeping up with the Joneses” a lot. But is there good evidence that we really care about what our neighbors have or that we change our behavior accordingly?

—Michelle

Yes and yes: There is good evidence of our tendency to try to keep up with those around us. In one recent paper, the economists Sumit Agarwal, Vyacheslav Mikhed and Barry Scholnick looked at the neighbors of lottery winners and discovered that they tended to buy more cars and other clearly visible assets. These “signaling purchases,” the study suggests, were influenced by the presence of suddenly rich neighbors, but the researchers found no increase in the savings or other invisible assets of the less lucky neighbors. Depressingly, those living near lottery winners were more likely to suffer financial distress and even bankruptcy.

These results show that our decisions aren’t just influenced by what we desire but also by our social drive to keep up with those around us. So it makes sense for us to spend a bit more time thinking about who we want to befriend and live next to. If we are going to try to keep up with the Joneses, we should pick the right Joneses.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

The polling averages now show Hillary Clinton with a significant lead over Donald Trump. Will these favorable polls help or hurt her?

—Josh

The forces here point in both directions. On the one hand, you can imagine that people who support the front-runner could say something like, “My candidate is going to win anyway, so I can stay home”—which obviously hurts their candidate. On the other hand, a candidate’s popularity could well reinforce itself and create a herding effect, which would help whoever is up in the polls.

Which of these two forces is more powerful? The evidence points to the herding effect: For better or worse, we just seem to like to follow.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Work as Play, Volunteer Value, and Shower Scheduling

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Any tips for encouraging kids to view their homework as play?

—Gordon

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I no longer enjoy my job, and I am considering quitting and volunteering for a few years at a local organization that does great work. Will my self-worth drop if I no longer have a job?

—Sabrina

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Is it better to shower at night or in the morning?

—Rachael

No question about it: at night. We get dirtier more quickly when we interact with the outside world, so showering first thing in the morning means that we will spend the rest of the day and all night in a grimy state. But if you shower at night, you will be clean while you sleep and thus maximize the number of cleanliness-hours per shower—clearly a better approach.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Fair Friends, Channel Choosing, and a Heartbreak Diet

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m organizing a long weekend of skiing with 10 friends who have very different financial situations. I’d like everyone to be able to pay what that they’re comfortable with, and I also want to avoid creating an awkward social dynamic. I considered charging everyone a low base amount and then asking the wealthier friends to pay extra, but that doesn’t seem quite right. What’s the best way to divide up the cost?

—Zach

Dear Dan,

Why do I still listen to the radio and watch live TV when I have access to all the same content from different streaming services, which lets me skip what I don’t like and more easily change my experience?

—Colin

One possibility is that you are listening to the radio and watching live TV because you don’t want to have the ability to switch. When you just experience something that cannot be changed, you are more likely to get into the flow and fully enjoy it. By contrast, when you are continuously monitoring the experience and asking yourself how happy you are, it can be exhausting, ultimately taking away from the sense of immersion. Sometimes the freedom to choose among options isn’t a recipe for happiness.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently experienced some turbulent emotional times, and I realized that I was eating a lot of chocolate and gaining weight. I am now wondering if chocolate really has mood-improving powers, as many people seem to think, or if I just gained weight for no good reason.

—Mia

Some research has found that chocolate can in fact boost your mood—perhaps due to compounds found in cocoa. Interestingly, women seem to be more likely than men to eat chocolate to try to boost their moods. That could mean that experiencing some heartbreak is a good diet for men but not for women.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like