Why Louisiana’s Ten Commandments law is a broken moral compass

Originally published at THE HILL.COM on 07/13/2024

When Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry (R) signed a law in June requiring the display of the Ten Commandments in every public school classroom in the state, it reignited the longstanding debate over the separation of church and state.

Opponents are pleading with federal judges to block the mandate before the school year begins in August. The American Civil Liberties Union and the Freedom From Religion Foundation are actively seeking to challenge the law in court, arguing it is “blatantly unconstitutional.”

From my perspective as a social scientist, a law requiring the Ten Commandments to be hung over every classroom across the state is flawed for reasons that go beyond its constitutionality. I see it as a fundamentally ineffective mandate, because heaps of research say so. And did I mention it would be a waste of tax dollars?

In the extensive research on human dishonesty, one clear finding emerges: Passive reminders of ethical conduct, like displaying the Ten Commandments, do not significantly influence behavior. To instill moral values and ethical behavior, active engagement and a sense of relevance are crucial. Simply hanging up a poster of the Ten Commandments on a classroom wall would not foster the active, lived experience of ethical principles.

Consider the Hippocratic Oath taken by physicians. Properly invoked, the Hippocratic Oath inspires students of medicine and practitioners alike to actively engage with its ethical calling and think about its principles at important moments, not just because it has been deeply ingrained in the fabric of the medical community. Unlike passive displays, active engagement creates a sense of commitment to ethical principles, which opens the door to more ethical behavior.

Louisiana’s new law exemplifies bureaucracy at its worst — it imposes a mandate based on a principle that extensive research has shown to be ineffective. It’s not just controversial; it will make schools feel as if they have dealt with the problem of ethics, when in fact they will not have.

Moreover, the assumption that the Ten Commandments can serve as a universal moral code is increasingly out of touch with contemporary American society. Over the past few decades, the relationship of the average American with religion has become more diffuse, and the influence of traditional religious codes has decreased.

Research conducted over the past decades on moral reminders concludes that active engagement with the moral reminder — such as the Ten Commandments — can decrease dishonesty. But, given Americans’ waning religiosity, that effect is diminished.

For the Ten Commandments to have an impact on thought or behavior, people have to first buy into the idea that the Ten Commandments are a meaningful set of moral rules. Displaying a moral code that doesn’t carry meaning is the equivalent of hanging a poster written in a foreign language.

Together, these two points mean that if someone wants to increase the ethics of our schools and the ethical behavior of our students, the first thing they need to ensure is that the set of moral principles has very deep and broad buy-in.

Next, the engagement with this set of ethical reminders has to be active and intentional. Of course, such programs are much more complex to carry out than simply hanging the Ten Commandments in different corners of schools — but they have the advantage that they might also work to have an impact.

Finally, the trend of setting up rules that are designed to make a political splash and maybe get some headlines but are not thoughtfully designed for efficacy further erodes our trust in politicians and institutions at large — government, corporations and even academia.

As these institutions lose their authority, there is a collective rejection of standard norms of behavior, which I believe are at play in our so-called “culture wars” and other societal trends that have upended American society in recent years.

The breakdown of trust in government and moral codes that historically guided Americans poses a critical question for our democracy: Can we still function effectively without a shared belief system? As we head into another election year, this question becomes even more pressing. Yet its implications extend far beyond politics.

Without a sense of mutual agreement on our ethical principles and without trust that the people leading us are truly interested in our long-term well-being, any efforts to improve behavior — whether through passive or active means — are doomed to fail.

Link to original publication: https://thehill.com/opinion/education/4768231-louisiana-ten-commandments-law/

Introducing – The Center for Advanced Bureaucracy

I’m not sure about you, but in the last few years, I have felt the creep of increased bureaucracy. In general, I think about bureaucracy as having two components. The first is positive, where we’re trying to make things structured, procedural, easier, and less time-consuming. The second is the negative one. This part is about the development of a bureaucratic sub-organization that often has different goals than the overall organization. This bureaucratic sub-organization often ends up serving itself rather than the organization as a whole. This is the kind of bureaucracy that I’m noticing more and more of, and it is deeply troubling me.

One of the challenges is that it is natural for the bureaucratic sub-organization to try and influence the organization as a whole to do less, take less risks, innovate less, and in doing so make the life of the people at the bureaucratic sub-organization easier. It is also tempting for the bureaucratic sub-organization to try and grow by making up new functions, new jobs, and hire more and more people that are part of the bureaucratic sub-organization. And finally, there are the impacts of bureaucracy on the way employees are being treated.

To examine this more carefully, I recently opened a website called the Center for Advanced Bureaucracy (https://centerforbureaucracy.com). Here, I detailed my reflections this way of thinking and share some warning. Check my video on “The Bureaucracy of a Red Sofa.”

Please follow the link (https://centerforbureaucracy.com), have a look, and let me know what you think.

In Defense of Mistakes

In a world that is hyper-brutal and punishing of mistakes, offenses, and missteps – small or large – on both social media and in real life, it might seem odd for me to promote making more mistakes. Yet, I want to make the case for making more and better mistakes.

I am an expert on mistakes. Not just in the purely theoretical or academic sense, but in the real-life sense. When I was nearly 18, an accident disfigured over 70% of my body with burns, removing nearly all functionality from my hands. I spent the next three years in a hospital missing out on many of the normal experiences of young adulthood. It could have filled me with rage, depression, or regret. Instead, it inspired my life’s work studying human behavior and trying to figure out what we can do to make our lives better. (It also inspired my signature half-beard.)

In my professional life, I have conducted countless studies that just didn’t work out the way I assumed they would. I have left positions under complicated circumstances. I had startups that failed. I’ve had interactions with colleagues that I wish had gone differently. Each of these experiences, while very painful at the time, were opportunities for observing myself and human nature. They became experiences of personal and professional growth.

I have also spent the better part of the past three years reliving a set of decisions I made and actions I took over a decade ago, around a now-infamous study of human behavior using car insurance data. Working in partnership with trusted colleagues, I did what was expected and right at the time. When the findings of the original study were called into question years later, we re-tested our assumptions, publishing results that put doubt on the original findings. When issues with the original data set were uncovered, we retracted the paper. Later we re-examined and replicated the findings, and in early 2024 published two papers that show that the effects of signing first matter (links to the papers are at the bottom of this post), but also that they matter in a more nuanced and complex way. Such is the scientific process. (See link to my official statement about this event).

As I was trying to understand what went wrong with the 2012 paper, people were very quick to criticize and question my professional judgment, casting a shadow over my life’s work. “Where did it all go wrong?” I have asked myself many times a day for the last few years. I have looked long and hard, but given that so much time has passed, I have come up empty-handed, and I simply don’t know for sure what went wrong. “Should I have done things differently?” Evidently. But as I examine all my decisions, I feel that I did the best I could at the time. And I’m okay with that.

Do I wish I did not make these mistakes? Of course. And, not at all. I obviously wish I did not make these specific mistakes, but in general, I accept these circumstances and continue to believe wholeheartedly that mistakes are essential to growth and evolution. Which brings me to my argument: We should all be making more and better mistakes.

What do I mean by that? To start, there is no reward without risk. Think about venture capitalists or investors in the stock market. As they approach their portfolios, they know that getting higher returns necessarily means taking greater risk. Risk, in the context of investing, is about investing in both sure things and in long shots.

Sometimes we also take risks to invest in ourselves or try something new – moments in our lives where we take a leap of faith and hope that things will work out. There is an expectation and understanding that some things will work out and some won’t, but overall, we know that we will be better off for having tried. Succeed or fail, the secret to success is charging forward boldly in new directions.

As a professor, I teach students about the logic, or lack thereof, in taking risks. We do case studies on Amazon’s fail-fast approach. We openly analyze past mistakes to learn from them. We talk about fostering cultures that will help us avoid another O-ring disaster.

There are mountains of self-help books and countless life coaches in the world, each telling us in their own ways that it is imperative to live in service of our desires, free of judgments of others and with more forgiveness for our shortcomings. “It’s okay to fall down. You just have to get back up.”

But the case for mistakes does not end here. It is not just about trying more and accepting more mistakes as the price of learning and success.

I am also advocating for better mistakes. What do I mean by better mistakes? We need to do the wrong thing the right way in order to maximize our learning. Specifically, we should aim to make more mistakes from bold action and fewer mistakes from inaction.

Popular wisdom says that when we look at our life in general, we will feel the most regret over the things we didn’t do. And yet, asymmetrical fear of regret leads us to fear mistakes from bold action more than mistakes from inaction, making us less likely to try new things – and more likely to do nothing.

When it comes to making the case for better mistakes, it means that we should be bolder and a little more fearless, by making a particular effort to make more mistakes from action. Taking calculated risks with a clear objective and having the courage to dust ourselves off if these risks don’t pan out. And try again.

Take, for example, the recent testimony of the three university presidents in front of Congress and the rest of the world. There is no question that this was a tragic performance that set academia back years, at a cost of public opinion that will take decades to rebuild. My sense is that these three university presidents should have dusted themselves off and worked even harder to tackle head-on the violence and hatred on their campus. This of course is a tall ask, and some of their efforts, particularly the more novel and creative ones, might have backfired. Yet, they should have taken more risks and tried different and novel approaches that might have contributed to their universities and to our understanding of how to help people to live in peace and civility with each other.

Sadly, the reactions to their testimonies prompted universities to do the exact opposite. Instead, universities now seem to be working hard to do as little as possible in order to fly under the radar. They seem to be largely motivated by a hope that students, faculty, trustees, and donors will soon forget about this particular war, and maybe even stop paying attention to anything that happens in the world altogether.

If we did more of the opposite of doing nothing and instead took bolder risks, would we more frequently experience the pain of erring, hit ourselves over the head, and say, “Why did I do this?” Sure, we would. But by accepting the downsides of bold action, we also increase the chance that we will learn something useful about how to move forward. If universities took bolder risks, maybe they would have lived up to their social mission and helped all of us better understand how to reduce hate, improve dialogue, and more.

At the end of the day, the progress of society and the success of any individual is made based on the totality of actions. And the biggest enemy of progress is fearing mistakes so much that we end up doing nothing.

To be sure, society can’t function without rules, boundaries, and consequences, but they should be proportionate. We must change the way we judge one another, to allow room for rehabilitation, reconciliation, or recompense. We must promote safer environments for failure, growth, and learning. Otherwise, we will motivate subterfuge among those who try and fail, and instill fear among those who might’ve tried but couldn’t stomach the potential aftermath.

For my part, I am planning on many more years of mistakes. I don’t intend to let fear and regret drive my decisions. I want to keep learning and growing. I intend to continue to make my own mistakes, and I even hope to normalize making more of them. I am optimistic enough to believe that as a culture, we can find a way forward that encourages people to take risks, fall down, and then get back up.

In the words of the famous philosopher, Yoda: “Pass on what you have learned. Strength. Mastery. But weakness, folly, failure also. Yes, failure most of all. The greatest teacher, failure is.”

LIVE AND LEARN.

Irrationally yours,

Dan

Links to the papers

Link to the paper “How Pledges Reduce Dishonesty: The Role of Involvement and Identification“: https://tinyurl.com/ycpumrtk

Link to the paper “I Solemnly Swear I’m Up To Good: A Megastudy Investigating the Effectiveness of Honesty Oaths on Curbing Dishonesty“: https://tinyurl.com/53mbn5ws and see also a link to a discussion about this paper: https://youtu.be/AjQ58irCZGg

Predictably Irrational is 16 years old

Predictably Irrational was published on this day (Feb 19th), 16 years ago — 2008. This was just the beginning of the financial crisis of 2008, when we were all trying to understand what went wrong and what are the limits of human irrationality. Predictably Irrational came out at a good timing to help us rethink human irrationality.

I suspect that the crisis of misinformation and polarization that we are facing these days is even more severe and with consequences that are even more dire. Although the damage that we have caused ourselves in this misinformation and polarization crisis (not with bad intention, just by not understanding our human nature) is much slower-moving and not as clearly observable. Which translates into a relatively calm nonchalant approach, where we are not yet in the panic mode we should be in. This time too, I just wrote a book about these topics – Misbelief.

I know that it might seem that my books predict important breaking points in society, but this is not true. I had a few books in between these two that did not coincide with any large-scale crisis.

The Irrational, Episode #1: The Pilot

The Irrational is a TV show on NBC that is loosely based on my life and my research (very loosely). See a link to the show HERE.

Each episode is based on some basic psychological forces, and here I will elaborate on the psychology that is part of the action in Episode 1: The Pilot.

The main theme of this episode is: False Memories

The main psychological principle in this episode is memory; specifically, false memory. As Elizabeth Loftus has shown, we tend to think that our memory represents our experience in a perfect way. That it works like a camera and that it records events exactly as they took place. But, in fact, our memory includes not only things that happened to us, but also things we imagined, things that other people told us happened, and things we learned about in other ways – and all of these can become mixed with the things that happened to us.

In this episode Alec says one of my favorite sentences: “Memory is the great con man of human nature.” This sums up the idea that we overestimate our memory’s accuracy despite its unreliability.

For more information about False Memories see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Loftus

The main social science terms used in this episode are:

The cocktail party effect

The cocktail party effect takes place when the brain zeroes in on a specific stimulus, typically auditory, while disregarding other stimuli. The standard case is when a partygoer engrossed in one conversation amidst a lot of chitchat can suddenly hear their name (or the word fire, or sex) when it comes from a discussion that they are presumably not hearing.

Surprisingly, the cocktail party effect suggests that this selective attention takes place after the meaning of the auditory signal is processed which means that at some level we hear the words, but actively suppress them before they arrive at our full consciousness.

For more about the cocktail party effect see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cocktail_party_effect

Guilt

Guilt is an emotion that takes place when a person feels badly about compromising their own standards of conduct. It is an outcome of first internalizing the standards of society (don’t litter, don’t lie, etc.). Next, we judge ourselves relative to these social standards, and finally we feel bad — guilty — when our own behavior falls short relative to these social standards.

It is also interesting to contrast guilt and shame. The main difference is that shame takes place only when someone else is watching (or might be watching), and the shame comes from the feeling of being judged by another person. Guilt on the other hand is independent from anyone watching, which means that guilt means that a person is their own judge. From this view, we can think about guilt as a more evolved and more desirable emotion, where a person internalizes the values of society and judges themselves relative to those standards independent of anyone else watching or not watching.

For more about Guilt see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guilt_(emotion)

The identifiable victim effect

The identifiable victim effect is the tendency of individuals to offer more help when a specific, identifiable person (“victim”) is in need of help, as opposed to a large, vaguely defined group with the same need.

This idea is captured by quotes from both Mother Teresa and one attributed to Joseph Stalin.

“If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.” ― Mother Teresa

“A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths are a statistic.” ― Joseph Stalin (possibly)

The identifiable victim effect is based on two components. The first is that people are more inclined to help an identified victim than an unidentified one. The second is that people are more inclined to help a single identified victim than a group of identified victims.

Although helping an identified victim is commendable, the identifiable victim effect is considered a bias, because it causes us to take less action when we don’t know much about the person in need, and because it causes us to act less as the number of people affected by a tragedy increases.

For more about The identifiable victim effect see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Identifiable_victim_effect

Memory

Memory is often thought of as an information storage and retrieval system. But we should think about it more like an informational processing system with explicit and implicit functioning consisting of a sensory processor, short-term (or working) memory, and long-term memory. Importantly, while we often place a lot of trust in the accuracy and validity of our memory, the reality is that memory is an imperfect repository of information, and its constructive processes change memories over time. In short, memory is less reliable than we think it is. Of course, with the increase of Alzheimer’s disease diagnoses, we are made more aware of the importance of a good functioning memory. We also worry more about losing this very important part of ourselves – a part that is at the core of who we are.

Paradoxical persuasion

Paradoxical persuasion starts with the very simple observation that convincing anyone of anything is incredibly difficult. Just think about the last five years and ask yourself how many people have you been able to convince during that time? Similarly, ask yourself how many times over the last five years somebody else has convinced you that you were completely wrong about something? The reality is that when we engage in an argument we start counterarguing even before the other person has finished their sentence (they of course do the same thing), which is why at the end of a conversation in which two people try to change the other’s opinion, they are often even more steadfast in their own opinion because instead of listening, they have been engaged in arguing for their opinion. Paradoxical persuasion approaches arguments differently by asking people to think about the minute details of their argument. With this approach people often realize that they have not thought carefully about their own opinions. While the person that has considered their position more carefully doesn’t become convinced that they were completely wrong, they often realize that they shouldn’t be as committed to their original opinion as they were before.

For more about Paradoxical persuasion see: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1407055111

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a disorder that develops in some people who have experienced a shocking, scary, or dangerous event. While it is natural for people to feel afraid during and after a traumatic situation, PTSD is a disorder where the “fight-or-flight” response that was evoked during the initial traumatic event keeps on appearing in the person’s life a long time after the event has passed. People with PTSD have intense, disturbing thoughts and feelings related to their experience through flashbacks or nightmares and they continue to experience a version of the trauma and are unable to put the traumatic event behind them.

For more about PTSD see: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd

Reciprocity

Reciprocity is a fundamental driver of human behavior. It is the idea that individuals tend to respond to the actions of others in a manner that mirrors the positive or negative nature of those actions. When other people are nice to us, we feel a need to be nice to them back. When other people are mean to us, we feel the need to act in kind. Reciprocity is also a social norm, meaning that beyond our need to reciprocate, we also feel a kind of social pressure to reciprocate.

What reciprocity means is that in our daily lives we are frequently much nicer and much more cooperative than the self-interested view of human nature would predict.

For more about Reciprocity see: https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/psychology/reciprocity#

Sense of control

How much control do you feel you have over your life? You may feel we have a lot of control, or you may feel you have very little. Having the right amount of feeling of control is what helps keep us balanced. Feeling that we have no control can lead to anxiety, depression, and learned helplessness. And, as I argued in Misbelief, feeling out of control is a main driver that leads us to seek out stories that blame someone else for our problems as a way to help us make sense of our situations.

For more about Sense of control and its damaging effects see: https://misbeliefbook.com (Chapters 3 and 4)

My favorite quote from this episode: “Memory is the great con man of human nature.”

My favorite psychological advice from this episode: When we have a negative experience that stays in our memory and we just can’t shake it out, one approach is to try and replace it with something else. We can try to imagine that something else – something specific – happened and do this every day for 100 days. Eventually, the bad memory will fade and be replaced by the better one.

And for fun, here are a few pictures from the set.

I just made up a term — Anachronistic Prejudice

Anachronistic Prejudice is a term I recently made up to describe a situation where we use current norms to judge something that happened long ago or to judge someone who lived long ago. The other element of Anachronistic Prejudice is that while we use the wrong norms, we don’t fully realize that we are doing so.

In my mind, this is one of the worst biases of our time in terms of its negative impact on society and on individuals.

How might we fight such a bias? Here is one way: When you find yourself judging people for something that happened five or more years ago, stop and think about how you behaved during that timeframe. For example, think about your sense of humor 15 years ago. Then think about how likely you would have been, in the same timeframe, to make the same mistake as you are judging them on. Next, add a 50% chance because you are likely to have an overly positive opinion about yourself.

Now go ahead and judge.

Inherent Goodness or Badness: A Reflection

An ancient question has been whether human nature is inherently good or inherently bad. From as early as I can remember, I thought that the right view is that human nature is inherently good. Over the years, my professional experience in social science gave me further support for that view. Why? Because if you consider that the main lesson from social science — that the environment matters! — you have to also believe in a deep disconnect between the potential of people and their ultimate behavior. You put people in one environment and they behave as angels, but put them in another environment and the same people can act in much much worse ways.

What this means is that behavior, good and bad is not a direct reflection on the goodness or badness of human nature and instead, it is to a large degree an outcome of the environment.

As someone who has internalized social science into everything I do, including my basic beliefs and approach to life, my conclusion was ended up being that people are inherently good and with the right environment this goodness can come out. Everything we see that is not great is an outcome of mistakes, bad information, a bad environment, and so on.

Recently, however, the images and stories from the brutal attacks of Hamas on Israel forced me to stop, think, and reflect, and that’s precisely what I have been doing. Should I change my belief about the basics of human nature? Should I update it?

I went over all kinds of evidence in the news and in social media — information that is impossible to reconcile with the idea that people are inherently good. But, even though I struggled with lots of evidence, at the end of the day, I decided that I’m not yet ready to accept that human nature is evil, and I am going to keep on holding onto the belief that people are inherently good.

Yes, it’s true that the evidence for people being inherently evil is much more powerful than I had imagined, and every day I see more and more examples of unbelievable brutality. But, I’m not yet ready to make this shift. Much like Jean Piaget’s approach to child development and their stages, I think that for me too, the evidence is there, but I’m not yet ready to move to a different developmental stage and to admit that maybe people are not as good as I once believed.

Or, maybe I just need to hold on to the goodness view for the sake of my own motivation. I know that we will all keep on revisiting this question over and over in the near future and I hope that in time we will find more reasons to view the world and the people in it in a more hopeful and positive way.

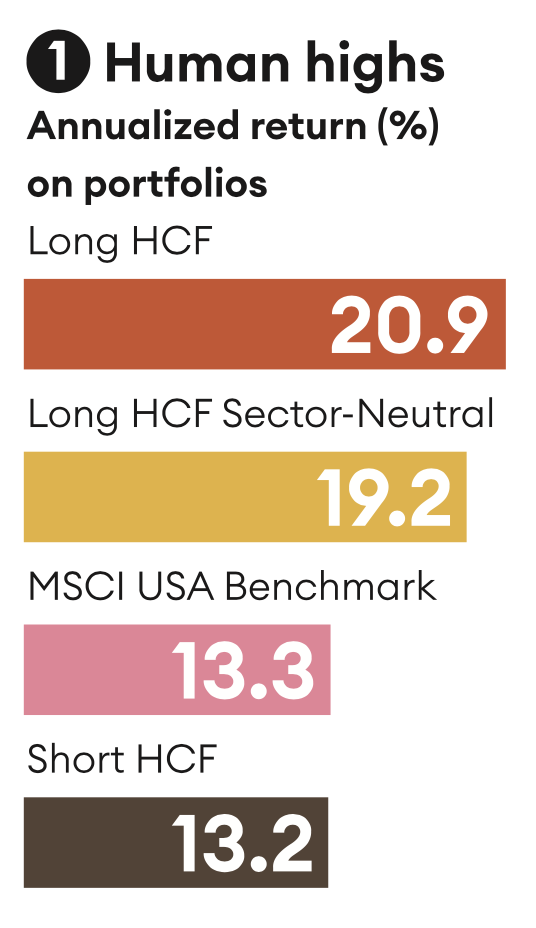

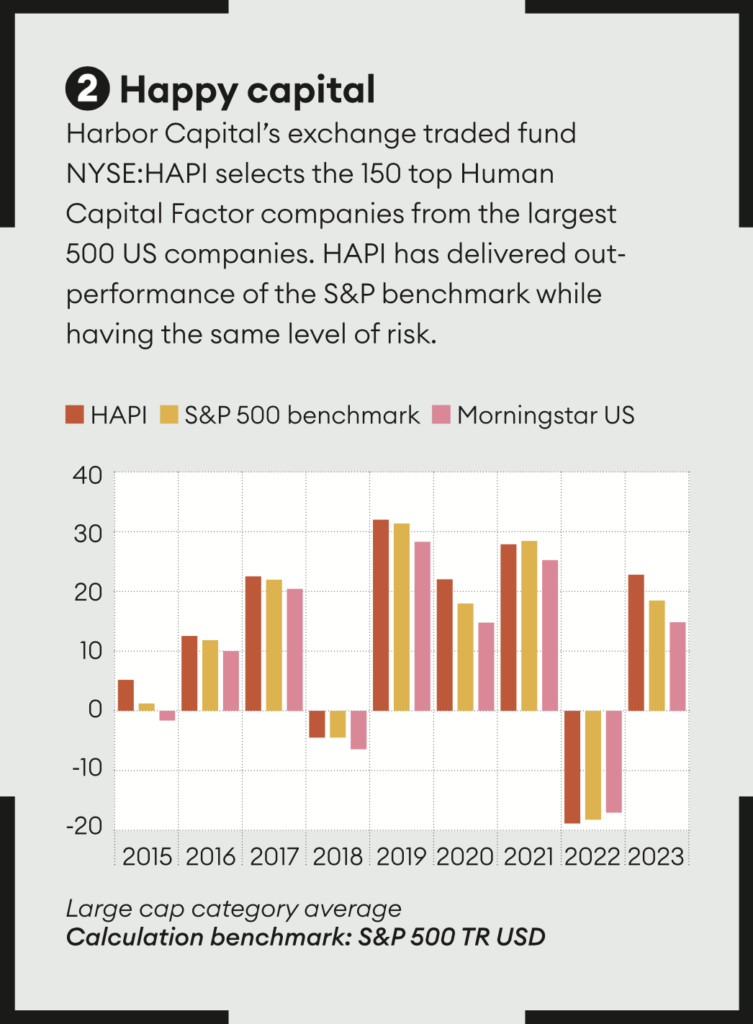

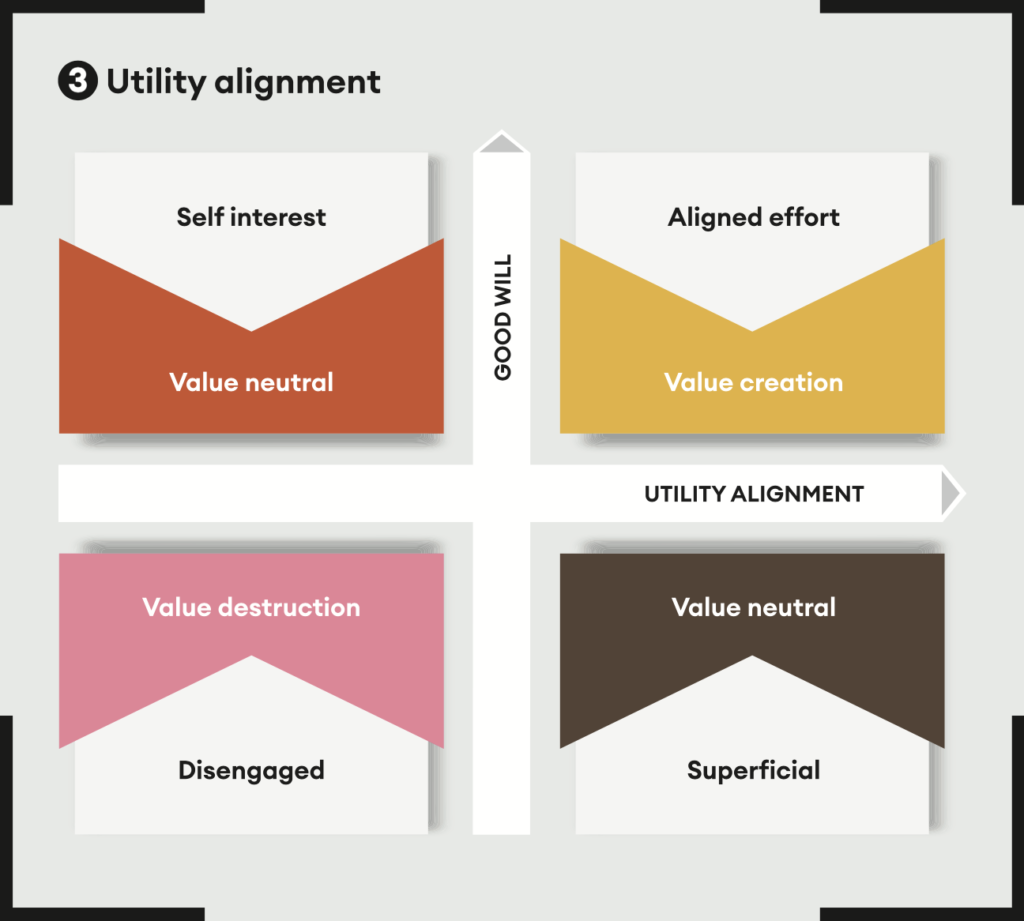

The human catalyst

A strong Human Capital Factor ignites growth.

“I only want to invest in fundamentals.” Such is a common statement from financiers. Yet these self-proclaimed ‘fundamental investors’ are people who regularly ignore a key aspect of a successful business.

Originally posted on December 1st 2023 here https://dialoguereview.com/the-human-catalyst/

Corrosive information, Shibboleth, Ramaswamy and my new book: MISBELIEF

A few weeks ago, David French wrote a very compelling and troubling OpEd in the New York Times, under the title: “The Articulate Ignorance of Vivek Ramaswamy.”

The main point focused on a response that Vivek Ramaswamy gave during the Republican debate to the question of whether Mike Pence did the right thing by certifying the presidential election on Jan. 6, 2021. Ramaswamy’s response was that if he was in Pence’s shoes, he would have “pushed for a new federal law to mandate single-day voting, paper ballots and voter identification.”

French then goes on to explain that this is “a crazy, illegal, unworkable idea on every level,” which of course it is. French then continues to wonder how can anyone make such an impractical and impossible statement. This is where French, and I suspect most people, miss an important shift in the current political communication landscape – a shift toward shibboleth.

What is shibboleth? As I explain in my new book MISBELIEF, the modern term shibboleth is based on a biblical story where two tribes, the Ephraimites and the Gileadites, pronounced the word shibboleth differently. After a bloody war between them, when someone tried to cross the river, they asked them to pronounce shibboleth and if the pronunciation was different from their own pronunciation, they person in question was killed. The way that social scientists use the term shibboleth is as a kind of linguistic password that identifies people’s belongingness to a group. This is also the key to better understanding our modern political discourse, and within it also understanding Ramaswamy and his comment.

My guess is that when Ramaswamy proposed his new federal law, he did not really mean it as a real solution to the question. Nor was he adding facts to the discussion. No — he was signaling. Imagine that Ramaswamy would have said something of the republican-run-of-the-mill category. Maybe he would have said that he would have gathered the Republican leadership to discuss the issue. Or maybe that he would have made sure to publicly register his protest. Any such more modest statements would not portray him as a real true Republican leader. They would just portray him as a standard Republican. In contrast, by saying something impossible and outlandish he is using shibboleth and marking himself as a person with the qualities of a true Republican leader.

This is where French was wrong in his analysis because he mistakenly assumed that the goal of Ramaswamy’s response was to communicate a true opinion and not to signal his loyalty and identity and suitability to Republican leadership.

While I hope that this analysis of the role of shibboleth in the current political discourse, this perspective should not give us any comfort and instead it should make us even more worried. In standard communication we expect people to say what they mean, to say the truth and to add facts to the discourse. Especially when the communication is public on well accepted media channels. When shibboleth takes the center stage and these basic assumptions no longer hold, the risk of false narrative increases dramatically.

The challenge with this analysis is that it doesn’t help us figure how to deal with a discussion that pretends to be about real information but is in fact a shibboleth kind of communication. What we need is to approach this problem in two ways: First, we need to understand this shibboleth strategy and figure out how to take some of the things that politicians say and treat them as loyalty statements, and not as informative speech. Second, we need to demand more from our politicians. We need to start having agreed upon standards for political discussions and it is best to set these clearly and before we get too deep into the election season, and ideally before the next debate.

P.S. Obviously, the problem of shibboleth is only limited to US politicians, and in other countries (Israel, UK, Brazil to name just a few) people, politicians, and social media are immune from this problem, but even so, it is useful to understand shibboleth and think about it as we go about consuming and producing information.

–Dan

If you would like to read my new book MISBELIEF, this page includes an option to order a copy for yourself + a copy to be donated to an educator. The book can also be found at Amazon, Bookshop.org, Audible, BAM, or Barnes & Noble.

Happy Birthday to MISBELIEF

Hello to All!

Today I am celebrating the release of my new book MISBELIEF: What Makes Rational People Believe Irrational Things. I hope you will find this topic as interesting as I have, and get a book, and learn about what I describe as a psychological machine that influences people’s beliefs and changes them, sometimes in a way that is very difficult to understand. If you are curious about this book, you can learn more about it here and here.

If you decide you want to read the book, this page includes an option to order a copy for yourself + a copy to be donated to an educator. The book can also be found at Amazon, Bookshop.org, Audible, BAM, or Barnes & Noble.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like