Ask Ariely: On Keepsake Conundrums and Proxy Practicality

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m planning a family reunion where relatives will be asked to bring photos and keepsakes. One side of the family, however, hasn’t been able to hold on to many physical memories, and I’m concerned that the lack of memorabilia will bring down the mood of the event. What’s the best way to handle this situation?

—Selena

Memories make us happier than we expect, even sad or seemingly mundane memories—and even memories that aren’t our own.

One study asked college students to write their favorite college memories on notecards. A month later the students read either their own memories or those of another student. Both groups reported boosts in happiness after writing and reading memories, even when the memories were about things that could be considered sad. The study was replicated in nursing homes in New Jersey: The residents who read memories, even ones that weren’t their own, reported feeling less lonely, more connected and happier.

These findings suggest that everyone at the reunion will be better off after looking at photos and scrapbooks. The reunion is also a great opportunity for family members to write down memories and stories that aren’t otherwise recorded, which could be a good start for enjoying memories at the next reunion.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently divorced after many years of marriage. Splitting our assets and accounts was a long and difficult process. Now I’ve discovered that my advance medical directive still has my ex-wife listed as my healthcare proxy. Should the situation arise, she can decide whether to keep me alive or disconnect me from life support. Should I find somebody else to take over this role or wait a bit, so as not to ruffle already hurt feelings or cause further practical headaches? What if I die in the meantime?

—Alec

You should certainly keep your ex-wife as your healthcare proxy, and not simply out of convenience or a desire to avoid giving offense.

As the doctor and medical writer Jerome Groopman has observed in one of his New Yorker Columns “Sometimes, however, a doctor’s impulse to protect a patient he likes or admires can adversely affect his judgment.” Dr Groopman then continues to describe one of his own cases: “I was furious with myself. Because I liked Brad, I hadn’t wanted to add to his discomfort and had cut the examination short. Perhaps I hoped unconsciously that the cause of his fever was trivial and that I would not find evidence of an infection on his body. This tendency to make decisions based on what we wish were true is what Croskerry calls an “affective error.” In medicine, this type of error can have potentially fatal consequences.”

My interpretation of Groopman’s observation is that it is often better for doctors not to have special feelings for their patients. Why? Because as lots of research has shown that it is difficult to be objective in making decisions for people we are attached to. We make more judicious decisions regarding people we care about less.

In your case, your ex-wife doesn’t care much about you these days. And because of that, should you sustain a serious injury or illness, the odds are in your favor that she will make more rational decisions on your behalf than she would have done during the days when she loved you deeply. Even if you do end up getting remarried, keep her as your healthcare proxy. There is no substitute for the rational coldness that comes from having your ex-wife make decisions for you.

This being said, don’t tempt her too much: Make sure she is not one of the beneficiaries of your will or life insurance.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

The (un-)expected link between the human and the artificial mind

Understanding the human mind is key to the better design of artificial minds.

A short report based on a paper by Darius-Aurel Frank, Polymeros Chrysochou, Panagiotis Mitkidis, and Dan Ariely

Technology around us is becoming smarter. Much smarter. And with this increased smartness come a lot of benefits for individuals and society. Specifically, smarter technology means that we can let technology make better decisions for us and let us enjoy the outcome of good decisions without having to make the effort. All of this sounds amazing – better decisions with less effort. However, one of the challenges is that decisions sometimes include moral tradeoffs and, in these cases, we have to ask ourselves if we are willing to allocate these moral decisions to a non-human system.

One of the clearest cases for such moral decisions involves autonomous vehicles. Autonomous vehicles have to make decisions about what lane to drive in or who to give way at a busy intersection. But they also have to make much more morally complex decisions – such as choosing whether to disregard traffic regulations when asked to rush to the hospital or to select whose safety to prioritize in the event of an inevitable car accident. With these questions in mind it is clear that assigning the ability to make decisions for us is not that easy and that it requires that we have a good model of our own morality, if we want autonomous vehicles to make decisions for us.

This brings us to the main question of this paper: how should we design artificial minds in terms of their underlying ethical principles? What guiding principle should we use for these artificial machines? For example, should the principals guiding these machines be to protect their owners above others? Or should they view all living creatures as equals? Which autonomous vehicles would you like to have and which autonomous vehicles would you like your neighbor to have?

To start examining these kinds of questions, we followed an experimental approach and mapped the decisions of many to uncover the common denominators and potential biases of the human minds. In our experiments, we followed the Moral Machine project and used a variant of the classical trolley dilemma – a thought experiment, in which people are asked to choose between undesirable outcomes under different framing. In our dilemmas, decision-makers were asked to choose who should an autonomous vehicle sacrifice in the case of an inevitable accident: the passengers of the vehicle or pedestrians in the street. The results are published under open-access license and are available for everyone to read for free at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-49411-7.

In short, what we find are two biases that influence whether people prefer that the autonomous vehicle sacrifices the pedestrians or the passengers. The first bias is related to the speed with which the moral decision was made. We find that quick, intuitive moral decisions favor killing the passengers – regardless of the specific composition of the dilemma. While in deliberate, thoughtful decisions, people tend to prefer sacrificing the pedestrians more often. The second bias is related to the initial perspective of the person making the judgment. Those who started by caring more about the passengers in the dilemma ended up sacrificing the pedestrians more often, and vice versa. Interestingly overall and across conditions people prefer to save the passengers over the pedestrians.

What we take away from these experiments, and the Moral Machine, is that we have some decisions to make. Do we want our autonomous vehicles to reflect our own morality, biases and all or do we want their moral outlook to be like that of Data from Star Track? And if we want these machines to mimic our own morality, do we want that to be the morality as it is expressed in our immediate gut feelings or the ones that show up after we have considered a moral dilemma for a while?

These questions might seem like academic philosophical debates that almost no one should really care about, but the speed in which autonomous vehicles are approaching suggests that these questions are both important and urgent for designing our joint future with technology.

Ask Ariely: On Discussing Delays, Remembering Regret, and Valuing Veracity

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m one of the backers on Kickstarter of the Irrational Game, the social-science-driven card game that you developed to help us improve our “ability to predict how events might unfold.” You were late to deliver, but it came out great.

Usually, when I back something on Kickstarter, I forget about it until the product is delivered. But your team sent updates about the delays in design, testing and more. I know you intended to keep your backers informed, but the reports on these hiccups left me with the impression that you had poor foresight and management skills. Are such negative updates a bad idea?

—Lucian

You’re right on two counts. First, my planning and administrative skills need work. Second, there are real disadvantages to keeping people posted on problems with a project.

Once people decide to support a Kickstarter venture, they usually don’t think much more about it. They re-evaluate their decision only when they are reminded of it, and if the reminders are bad, they probably take an increasingly dim view of the project. So our approach turned out to be unhelpful. We often judge satisfaction by contrasting what we expect with what we get. When our backers were reminded of the game, the news was usually bad, which prompted some to sour on a pretty good project.

This would be different if the project were a big, focal undertaking for investors. In that case, they would think about it all the time anyway—which means that there would be little harm in informing them of snags that were on their minds anyway.

I must admit that, before your question, I hadn’t thought about this problem of negative reminders. I will try to be quieter next time.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I vividly remember thinking about buying Amazon stock when I was 12. I bought several stocks in my youth, but not Amazon—a mistake that has colored my entire financial future. I feel terrible regret. How do I get over it?

—Josh

Regret is a powerful motivator. We experience it when we see one thing and envisage a better, alternative reality. In your case, the contrast in realities is clear, and the thought of those imagined lost riches is making you very unhappy. Unfortunately, unless you move to some island with no internet access, you will probably keep on experiencing some of this regret with each new mention of Amazon.

The only partial cure I can suggest is trying to think about your decisions in a holistic way, paying some heed to your good decisions rather than obsessing over your bad ones. Ideally, you would take one of those wise calls and condition yourself to think about it every time you are ruing your Amazon miss.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Do ideologues, who by definition care a lot about something, lie more for their causes?

—Paula

Absolutely. Lying is always a trade-off between different values. When ideologues face a trade-off between the truth and the focus of their political passion (the idea, say, that the U.S. is an evil imperialist power or that Obamacare is a socialist plot to destroy America), they tend to be more willing to sacrifice the truth if they think it will help them to convince the idiots on the other side to do the right thing. Unfortunately, the last election suggests that more Americans have become ideologues.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

In the Home of the Free, Why Are So Many People in Prison?

The high rate of incarceration in the United States is fraught with social and economic costs. Relatively recent increases in our incarceration rate make us an international outlier and carry a price tag of more than $80 billion annually (more than quadruple the 1980 corrections expenditures). This is despite an overall reduction in crime rates between 1990 and 2012.

In addition to the overall incarceration rate, there is a staggering gap between the incarceration rates of black Americans and white Americans. The gap is most clearly seen between black and white males. Based on 2001 incarceration rates, nearly 1 in 3 (32.2%) black males will will be sentenced to prison during their lifetimes, whereas the rate for white males is 5.9%.

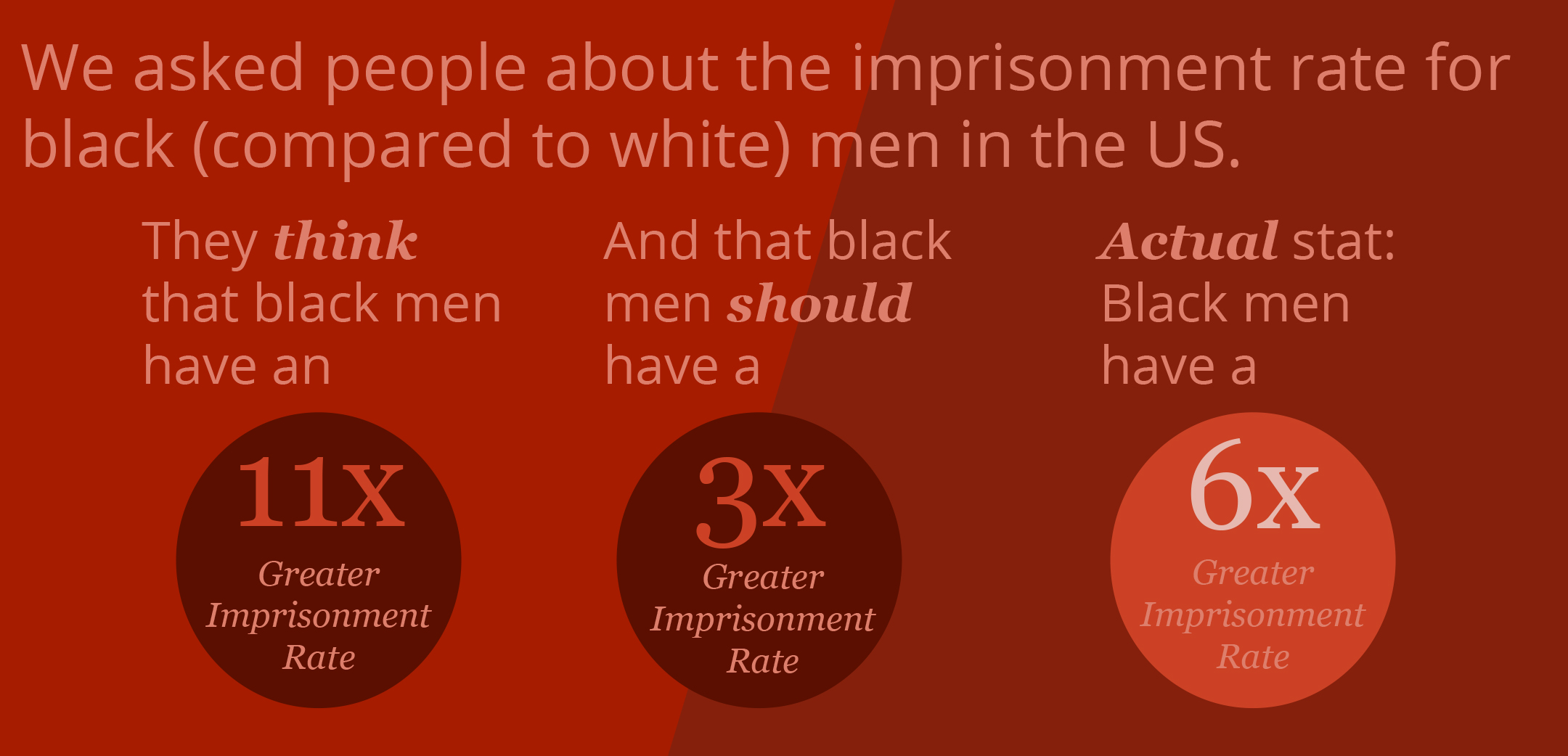

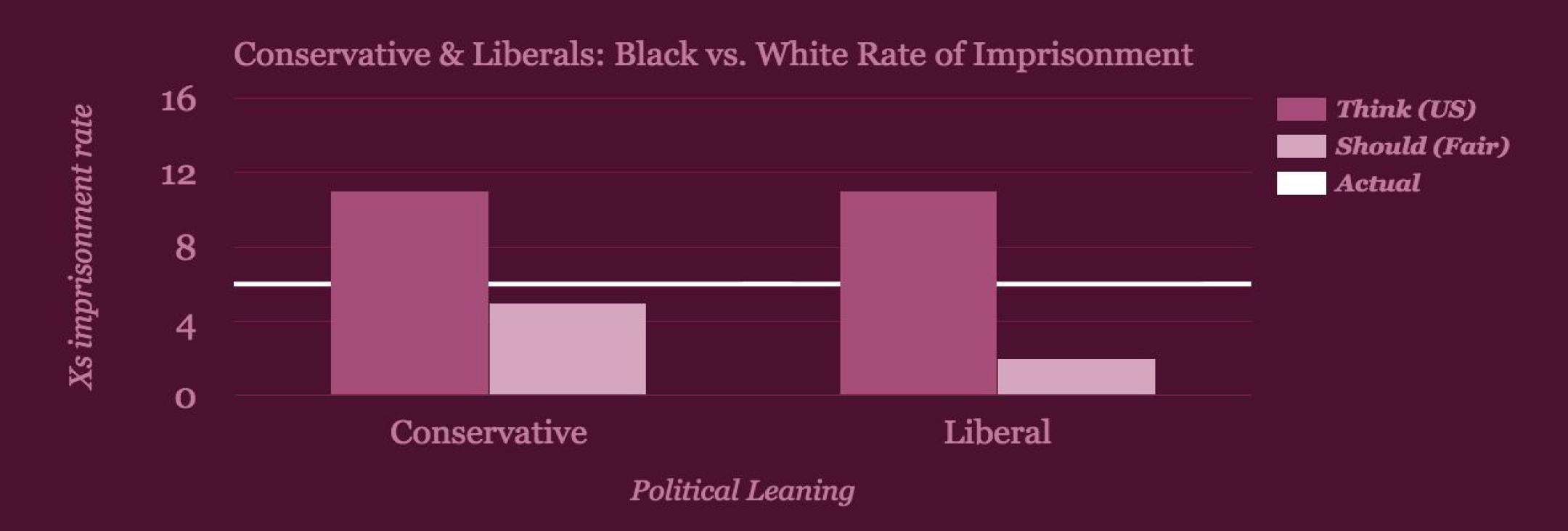

Topic 5 in Fair Game? asked users to think about how much greater the rate of imprisonment is for black versus white men in the US and how much greater it should be in a fair world.

On the whole, our users estimated that black males have an 11x greater imprisonment rate than white males. In reality, recent data shows the imprisonment rate is 6x greater.

How much more greater do people think the imprisonment rate should be in a fair world? 3x more likely.

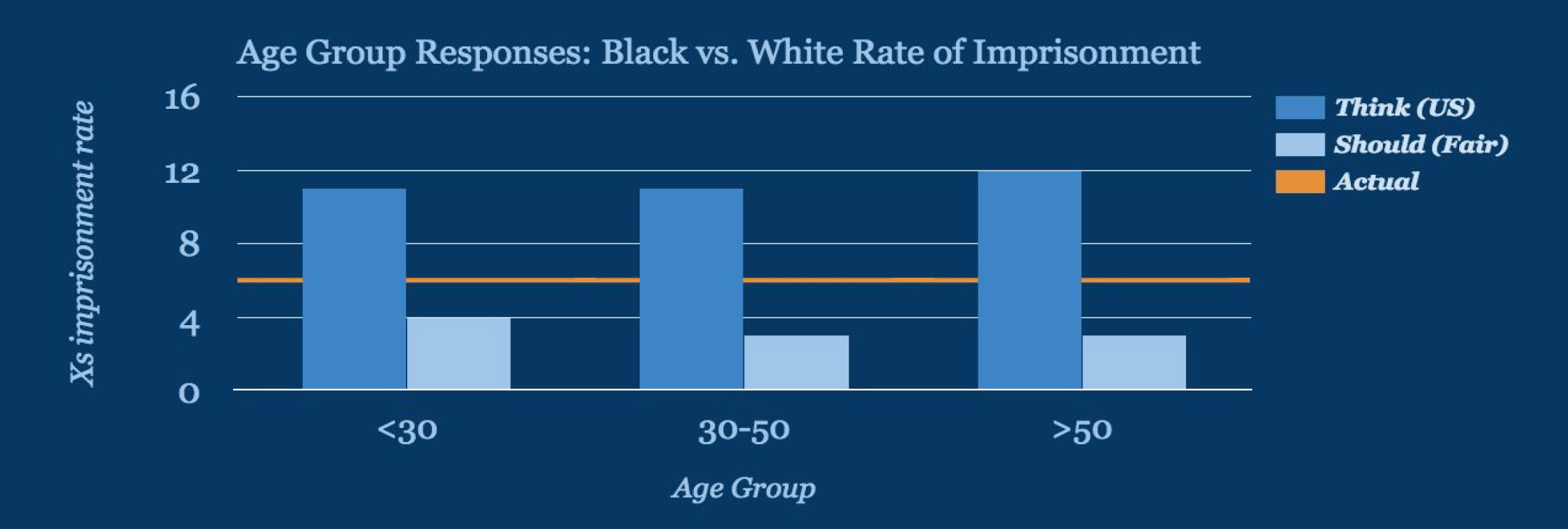

Estimates for the greater likelihood of imprisonment were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair.

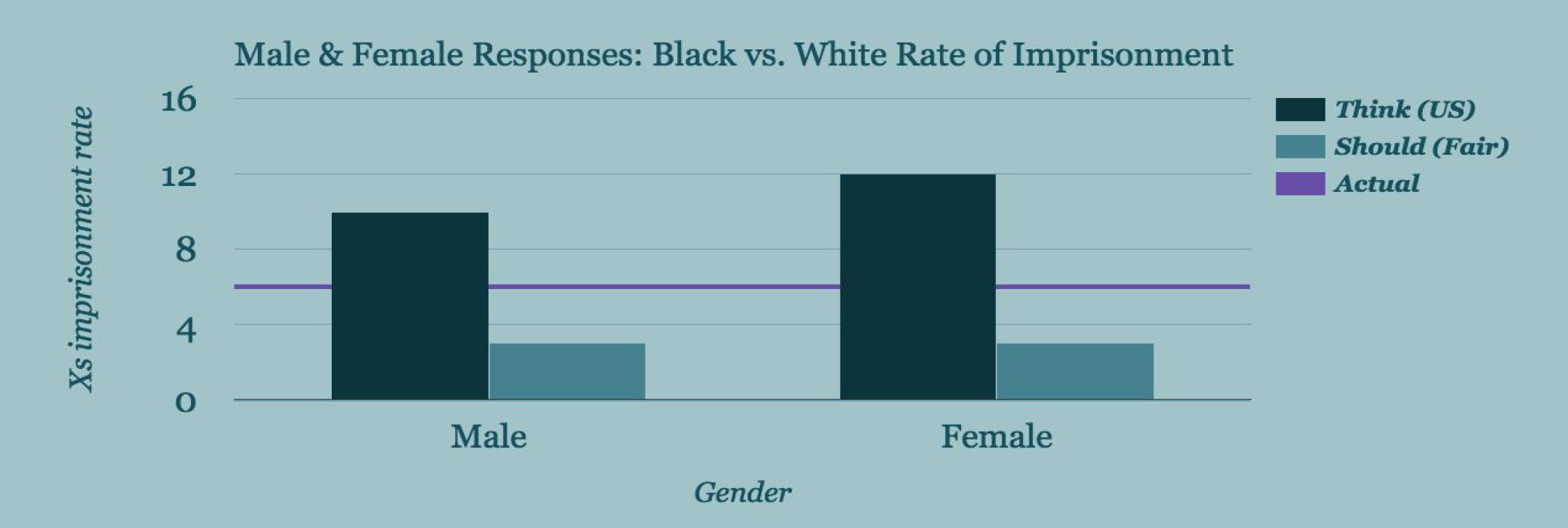

What about gender? Males and females differ in their estimates of the greater rate of imprisonment, estimating 10 and 12 times greater likelihoods, respectively. But they agree in what they think a fair rate would be — 3x.

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal estimate the same (11x) greater rate of imprisonment. In terms of how much greater the rate should be in a fair society, conservatives answered 5x more likely and liberals answered 2x more likely. So although their understanding of the world is similar, their notions of fairness, for this topic, are very different.

Together, the data reported here suggest that people overestimate the gap in the incarceration rate by race. And they would reduce the size of the gap that they perceive. There are many factors that contribute to the racial disparity in imprisonment rate. The so-called War on Drugs may be the single largest factor, with Blacks and Hispanics disproportionately representing those in state prisons for drug offenses and sentenced for federal drug trafficking offenses. These offenses often carry harsh mandatory sentences, further exacerbating the disparities. Discrimination has been shown to be a problem at multiple levels of the criminal justice system, including law enforcement, prosecution, sentencing, and reentry to society.

Beyond the pervasive problem of racial discrimination, another consideration is more purely economic– the growth of private companies building and running prisons. Oliver Hart (a 2016 Nobel prize-winner in Economics) and his coauthors have written about private prison contracts and their tendency to induce the wrong incentives by not focusing on outcomes.

There are economic benefits to reducing the prison population, including reduced costs for taxpayers (construction, maintenance and operation of prisons) and of course income and opportunities for those who would otherwise have been imprisoned. Several states have drug decriminalization ballot initiatives in this year’s election and it will be interesting to see whether these have an impact on the rate of imprisonment in those states. What other possibilities might decrease the prison population and reduce the racial disparity in the rate of imprisonment?

Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

The Trust Factory

Hey everyone, I hope this blog post finds you well. Recently, I wrote a short paper about trust….

The paper, Trust Factory, discusses elements of trust; specifically regarding the way organizations can interact with individuals to build trust. If you’re interested in reading the paper, you can view this link.

The paper talks about how humans tend to trust one another. But does it work the same way when it comes to trusting organizations?

A community of trust is required to survive. That’s what trust is based on.

Understanding that, what can organizations do to gain the trust of their consumers/users? I outline five key tools that allow us to trust each other: long-term relationships, transparency, intentionality, revenge and aligned incentives.

View the paper by clicking on this link.

Trustfully yours,

Dan

On Fairness — please join us

What is fair?

According to Merriam-Webster:

: agreeing with what is thought to be right or acceptable

: treating people in a way that does not favor some over others

: not too harsh or critical

Many people can tell you when something is NOT fair (especially children, who test this concept more thoroughly than any scientist could)! Injustice may be an easier phenomenon to spot in the world (especially when we are the victim or perceived victim).

Does society view what is right or acceptable through a single lens, or does an individual’s unique background and experience shape their perception of fairness? In our new app, you can join in by answering questions about aspects of life in the United States. Do you think the world that we live in is fair? What should the world look like? Give your opinions and be a part of this large-scale social expression. You may learn something about yourself and about society. And you’ll help us answer the question, “Is life for everyone in the United States a Fair Game?”

To download for Apple:

https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/fair-game/id1138020713?mt=8

To download for Android/Google:

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.advancedhindsight.fairgame

Ask Ariely: On Honesty with Asperger’s, Adequate Achievements, and Favorable Futures

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My 19-year-old son has Asperger’s syndrome and is incapable of lying. He tends to see the world in absolutes and struggles with white lies. We have urged him to sometimes compliment people to spare their feelings, but he thinks it’s important to be brutally honest. He says, “What if you praise somebody’s ugly drawing and they then try a career as an artist? Why tell somebody that their new haircut looks great when you could warn them that they will be teased about it?” Have you looked into the ways that dishonesty may be different for those on the autism spectrum?

—Bill

I wrote a book about dishonesty and lecture frequently about it. Over the years, many parents have come to me after a talk to tell me about children who just can’t lie—and the children usually turn out to have some form of autism. Recently, I brought this up with Murali Doraiswamy, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, who confirmed that many children on the autism spectrum do indeed have a hard time being untruthful.

This is caused, he added, by the trouble they have with what specialists in the field call “theory of mind”—that is, the basic ability to put ourselves in somebody else’s shoes and empathize with their perspective. Most of us are able to ask ourselves, “How would that person feel if I told them that their haircut is unflattering or that they smell?” Many young people with Asperger’s don’t tend to think this way, so they often don’t develop the habit of telling white lies for reasons of politeness. They don’t learn to dial down unnecessarily hurtful truths to spare another person’s feelings.

My view is that social politeness often acts as training wheels for more serious lying, so children who don’t understand white lies often don’t develop the ability to lie on a larger scale—which may not be such a bad thing. Maybe we should try a president who has Asperger’s?

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

If human beings were tools, which tools would we be?

—Kelly

The best analogy for describing human nature is a Swiss Army knife.

First, it is useful for many different tasks. Second, the Swiss Army knife gives us a lot of tools, but none of them (no offense to the Swiss) are that great. The knife is small; the screwdriver is hard to use; the can opener is OK but time-consuming to operate. And third, everything we do with a Swiss Army knife takes some time—we have to figure out which tool we want, find it, dig our nails into its little notch and yank out the desired tool.

Together, these features echo human nature: We aren’t really ideal for anything and can be a bit slow to get going, but we can do a decent job on many different challenges.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What is the most important attribute to look for in a long-term romantic partner?

—Ed

Low expectations. Much of our happiness depends on relativity—on comparing what we have with what we expected to have. In long-term relationships, we’re bound to be disappointed at some point. But if we adjusted our expectations, we might be pleasantly surprised from time to time.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Family Photos, Moving Money, and Authoritative Acronyms

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I consider myself a steadfast atheist, but I have an irrational dilemma: Every time I want to throw away things that I no longer need, I find myself unable to chuck out anything that belonged to my parents. I can’t even part with their old pictures, which I have digitized and stored permanently on my hard drive. Am I being ridiculously superstitious?

—Eve

Religious belief and superstition aren’t really the same thing. Paul Rozin of the University of Pennsylvania has done excellent research showing that we are all superstitious, to some extent. In one of his experiments, participants were asked to throw darts at a target and were rewarded the closer they got to its center. Sometimes the center was the image of a beloved figure like President John Kennedy; sometimes it was someone widely despised, like Saddam Hussein.

People hit the bull’s-eye more for Saddam and missed more for JFK. They knew, of course, that pictures aren’t the same as people, but they still attached some of the person’s symbolic meaning to the images, which made it harder to harm them.

This type of emotional link means that when you think about throwing out your parents’ belongings, you feel as if you are discarding a part of them. My advice? Send the items that you don’t want but can’t destroy to your siblings or other relatives and let them deal with them.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m renting an apartment with two friends. One of them is moving in on August 24. I plan to move in on August 29, and the third friend is planning to join us in early September. Our landlord will charge extra rent for those days in August. Who should pay?

—Randy

The right way to split the cost depends on the timing and sequencing. If the lease was always set to start on August 24, then you should all split the cost because you all undertook the responsibility of starting the contract together. But if the contract could have started on any day, and your first friend pushed you into starting it on August 24, that friend should be on the hook for funding the extension. Fairness mandates considering the process here, not just the final outcome.

That said, remember that you’re all going to be roommates, perhaps for a long time, and starting your joint life together by protracted haggling may open the door to years of annoying accounting discussions (“You had an extra swig of the milk, so you owe me 75 cents”) rather than years of deep friendship. With this in mind, I suggest dividing the rent equally—but also asking the people moving in early to do more to set up the apartment, call the cable company, get basic supplies and figure out where the furniture goes. That way, they will contribute more to the overall endeavor but in a way that is compatible with long-term friendship.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

We have lots of meetings at my office, and when I speak up, I often worry that as a rather junior female employee, I don’t sound as if I have enough authority. Any advice about how to seem more commanding?

—Katherine

One of the best ways to increase your perceived authority is to start using acronyms. My favorites are WAG (Wild-Ass Guess) and SWAG (Scientific Wild-Ass Guess). My SWAG is that deploying a few well-placed acronyms the next time you make a point will give your gravitas quotient (or GQ) a boost.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Losing Leftovers and Stressful Situations

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

At a holiday potluck that I attend each year, the hostess asks each guest to bring a specific dish. We always wind up with too much food, but the hostess never asks us whether we would like to take any leftovers home. I think that the food I made and brought should be considered mine. So who do the leftovers belong to, the hostess or the cook/guest?

—Sigrid

This is a tricky one. Usually, if we are invited to someone’s house for dinner and bring, say, a bottle of fine whiskey, we wouldn’t expect to take the rest of the bottle back home with us. But a potluck isn’t your standard dinner party, and it isn’t clear what rules apply. You gave the food, which was accepted by the host—but she did so on behalf of the group, which didn’t finish it.

Ethics aside, I see three practical ways to resolve the problem. First, you could make something that is physically hard to separate from the dish in which you brought it. If, for instance, you brought crème brûlée in a large ceramic dish, you’d make it clear that the dish was yours, and because it would be difficult to separate it from the leftover dessert, you would get to take them both home.

Alternatively, you could bring your contribution in two containers, hand one to the host and tell her that you have another container in case your fellow diners polish off the first one. You wouldn’t have to hand over the second part of your offering unless it turned out to be needed, and you’d have a decent shot at getting to take it home.

Or you could whip up a crowd-pleasing recipe that you happen not to like. The point of a potluck is to have fun with friends, not to fret about who gets what at the end. So just make something you don’t care for. You won’t care who inherits the leftovers, and you’ll enjoy the party more.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I went to the bathroom at a new restaurant in town only to find a large, modern-looking stainless-steel urinal, without partitions, which put everyone in plain view of his fellow patrons. I tried to finish my business quickly and get out of there. Am I the only one made uncomfortable by such arrangements?

—Greg

Actually, many men are made uneasy by such bathroom settings, but I suspect that you didn’t finish your business any faster.

In 2005, my students and I carried out an experiment at MIT. Sometimes, we had one of our students stand at the middle urinal in the men’s room, pretending to go and waiting for unsuspecting visitors. Other times, we didn’t have anyone from our team at the urinals. In all cases, we had a student hiding in a nearby stall with a recorder.

That let us pick up two aspects of urination: its onset (from the time a subject situated himself at the urinal to the moment when we first heard liquid sounds) and its duration (until those sounds stopped).

We found that men took longer to get going when they had company nearby, presumably because of social stress. But once they started, they finished faster—again, presumably because of stress and the desire to get out of there. The total amount of time was slightly slower than when men were left alone.

Of course, our participants were undergraduates with splendid bladder control, so we might need to repeat this study with a more mature population.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Genuine Greetings, Moral Reminders, and Interest Aversion

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

We often greet each other by saying, “How are you?” But most of us probably don’t really want a long answer. Why do we do this?

—Warren

Dear Dan,

To reduce cheating at the high school where I teach, we ask students to sign an ethics code before each exam and on every paper they submit. I’d estimate that they sign the code at least once a week. Your own research, I gather, shows that getting students to sign a similar ethics code just once helps to reduce cheating. What about signing it more often? Does overuse make it ineffective?

—Elliott

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I find it easy to avoid reckless spending. I don’t own a credit card because I hate the concept of interest, and I’m paying my daughters’ college tuition (they know that they have to pay me back) because if they took out loans, I’d have to co-sign and might be on the hook for the tuition and interest. Am I just more rational than other people?

—Wei

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like