Ask Ariely: On Snooze Strategy, Better Bottles, and Productive Procrastination

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m having trouble waking up in the morning. I set my alarm clock, but I always wind up hitting the snooze button or turning it off completely. Any advice? If I want to wake up at 7 a.m., what time should I set my alarm for, and how many times should I hit snooze?

—Phillip

Set your alarm for exactly the time you need to get up. Since you want to start your day at 7, you may be tempted to set the alarm a bit early (let’s say 6:40) and hit snooze a few times until it is 7 or maybe even 7:15. But if you pick this snooze strategy, your body can’t learn the conditioned response between hearing the alarm and getting up.

In general, our bodies do better when they can get used to a single clear rule: Get out of bed the moment the alarm sounds. When we play with the snooze button, our bodies get a confused message: Sometimes we hear the beeping and get up, sometimes we hear it and stay put for 10 more minutes, sometimes we lie there for another 20 minutes, and so on.

So just bite the bullet and get out of bed when the alarm tells you to. Do this faithfully for a few months, and the conditioning should start to kick in. It won’t be fun in the beginning, but over time, it should pay off. Good luck.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When I’m out for dinner, I occasionally encounter a wine so special that I buy a case of it to drink at home. But the subsequent bottles never taste as appealing as the initial one, so I wind up not only regretting the purchase of additional wine but also spoiling some of the wonderful memories of my night at the restaurant.

So why can’t I enjoy the same wine as much at home? Is there something special about the way the restaurant handles the wine or the glow of the original occasion?

—Eugene

After an excellent dinner out, we might remember the wine as impeccable. But we probably won’t realize that part of our enjoyment of the wine flowed from the flickering candles, the beautiful music, the tasty food and the charming company. At home, the same wine is just the wine, without the halo effect, and it isn’t the same experience. Psychologists call this phenomenon the “misattribution of emotions”: We assume that the source of our enjoyment is one thing when it is really another.

It’s almost never possible to revisit special experiences. The place where you spent your honeymoon, for example, probably won’t make a good family vacation spot: A few days of chasing the kids and trying to eke out a few hours of sleep will certainly taint (if not erase) the original memory.

Next time, enjoy the wine, commit the whole experience to memory, don’t try to relive it, and look forward to new experiences.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently started using a smartphone app to manage my to-do list, and I’m really enjoying it. Every night, I take some time to make my to-do list; every morning, I go over it; and as I tackle different tasks throughout the day, I check them off my list. I feel not only more organized but more productive. Is there good documentation about an increase in productivity from to-do lists?

—Lev

You might be experiencing some increase in real productivity, but my guess is that you are mostly experiencing “structured procrastination.” That is the feeling of productivity that we get from making lists and crossing things off them—which spurs us to spend time on things that make us feel productive rather than on being productive. I am not recommending that you stop using this app, but I hope that you will measure your productivity based on what you’re getting done in your real-life projects, not on racking up checkmarks.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

The Trust Factory

Hey everyone, I hope this blog post finds you well. Recently, I wrote a short paper about trust….

The paper, Trust Factory, discusses elements of trust; specifically regarding the way organizations can interact with individuals to build trust. If you’re interested in reading the paper, you can view this link.

The paper talks about how humans tend to trust one another. But does it work the same way when it comes to trusting organizations?

A community of trust is required to survive. That’s what trust is based on.

Understanding that, what can organizations do to gain the trust of their consumers/users? I outline five key tools that allow us to trust each other: long-term relationships, transparency, intentionality, revenge and aligned incentives.

View the paper by clicking on this link.

Trustfully yours,

Dan

On Advice and Daily Dilemmas

Have you ever had a burning curiosity or a puzzling life dilemma? Each week, many people write to my Ask Ariely column for guidance – and I’ve now created an app to help disseminate some of their questions and my advice.

If you’ve ever wondered what to eat when you’re heartbroken, how to effectively raise money for a charity, why you’re so willing to buy expensive beer, or why people tend to think God shares their beliefs, this app is for you.

Responding to people’s curiosities is one of my favorite parts of being a behavioral economist and researcher. I hope to share my enjoyment with you in this app, which features bite-sized excerpts from my latest book, Irrationally Yours, for easy reading.

The app is live now, available for Android and iOS users alike.

Happy reading,

—Dan

Fair Game? How many average workers’ salaries does it take to pay the CEO?

Inequality is an important topic and one that politicians and scholars spend a lot of time thinking about. But what does the general public think about inequality and the many ways it manifests in daily life? And how do factors like age, gender, or political leanings relate to our views on inequality?

Those are the questions we are exploring with Fair Game?, our new app that asks users what they think about the world as it is today and what they would want in a fair world.

We’re asking users about 13 different topics related to inequality, from wage gaps to opportunities for education, and will be sharing our findings every few days now through mid-November.

Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play. We’ll release a new question every few days until we get through all 13.

You can think about the first topic right now.

So far, the data show a consistent knowledge gap.

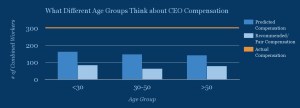

Our users estimate that the average CEO’s pay is equal to 151 average worker salaries. In reality, the average CEO makes the same as 303 average workers combined. What do people think CEOs should be paid in a fair world: the same as 72 average employees combined.

We also found some interesting patterns in what people think.

Younger people estimate the ratio of CEO pay to average worker pay to be larger than others do, and also think a larger ratio is fair. Perhaps younger people have lower salaries and therefore think the average worker’s salary is lower? Or they are looking ahead to larger, CEO-like salaries in the future, and that influences what they think is fair?

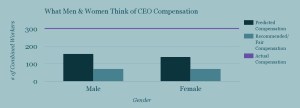

What about gender?

It is notable that males and females arrive at the same number for what would be fair (72 average worker salaries for each CEO), but differ in what they think currently exists in the world (158 for males vs. 140 for females). Perhaps the gender wage gap influences the perception of what salaries are in the world?

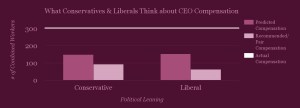

And political leaning?

People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal give similar estimates of what the current CEO to average worker salary is (149:1 and 152:1, respectively). But political leaning makes a big difference in what people think what would be fair. Liberal respondents believe 63:1 would be fair, whereas conservative respondents believe that 93:1 would be fair.

It is encouraging that political leaning does not dramatically change our respondents’ perceptions of the world. Both conservatives and liberals underestimate the magnitude of executive pay relative to worker pay in the United States. But their differing assessments of what would be fair suggests that conservatives and liberals might choose different approaches to reducing the executive-to-worker pay ratio.

Executive compensation is by no means a simple issue. In fact, the 2016 Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to researchers who considered how motivational factors should be related to pay, bonuses, stock compensation and the timeframe of company performance in order to achieve optimal levels. One of the winners, Bengt Holmström, told a reporter after hearing he had won, that he thought executive bonuses were “extraordinarily high” and compensation contracts were too complicated.

Has it always been like this? The ratio of executive pay to worker pay was 20-to-1 in 1965, when CEOs earned an average of $832,000 annually, compared to $40,200 for workers (adjusted for today’s dollars). In 2000, the number peaked at 376-to-1, and has since settled back down to the recent level of 303-to-1 (and some estimates are as low as 216-to-1). This increased ratio means that CEO compensation has risen dramatically over the past few decades, but the average worker compensation has not. In 2014 the average CEO made $16,316,000 compared to the $53,200 made by the average worker.

In an effort to promote greater transparency, the Securities and Exchange Commission will soon require every publicly traded company in the United States to disclose this ratio. A recent bill proposed in the California Senate calls for instituting a sliding scale of corporate taxation, with companies paying different tax rates based on their ratios and sharper increases for those with CEO to average worker pay ratios greater than 100-to-1. Other proposals for reducing the ratio and social ramifications of large gaps in companies include greater profit-sharing across employees and a more consistent relationship between (long-term) performance and bonuses.

A new online course for social entrepreneurs

At the Startup Lab (my incubator at Duke University’s Center for Advanced Hindsight), we aim to empower early stage startups to build better consumer health and finance products by teaching them how to apply both the findings and methods of behavioral economics to their products and business models.

While the in-depth Startup Lab program is limited to a small group of startups that go through our rigorous application process, it would be an injustice to not share some of its lessons with the greater community. So I’ve collaborated with +Acumen to create an online course to help social entrepreneurs make an impact – by designing products that change consumer behaviors for good. But what I am most excited about is the lesson on experimentation. I am always getting questions about how startups can experiment within their small companies (with few resources, especially time), and this course provides the tools for entrepreneurs to take a systematic approach to experimentation.

While the in-depth Startup Lab program is limited to a small group of startups that go through our rigorous application process, it would be an injustice to not share some of its lessons with the greater community. So I’ve collaborated with +Acumen to create an online course to help social entrepreneurs make an impact – by designing products that change consumer behaviors for good. But what I am most excited about is the lesson on experimentation. I am always getting questions about how startups can experiment within their small companies (with few resources, especially time), and this course provides the tools for entrepreneurs to take a systematic approach to experimentation.

Sign up for my Master Class with +Acumen on Changing Customer Behavior, now available here: http://bit.ly/2e11cOZ

On Fairness — please join us

What is fair?

According to Merriam-Webster:

: agreeing with what is thought to be right or acceptable

: treating people in a way that does not favor some over others

: not too harsh or critical

Many people can tell you when something is NOT fair (especially children, who test this concept more thoroughly than any scientist could)! Injustice may be an easier phenomenon to spot in the world (especially when we are the victim or perceived victim).

Does society view what is right or acceptable through a single lens, or does an individual’s unique background and experience shape their perception of fairness? In our new app, you can join in by answering questions about aspects of life in the United States. Do you think the world that we live in is fair? What should the world look like? Give your opinions and be a part of this large-scale social expression. You may learn something about yourself and about society. And you’ll help us answer the question, “Is life for everyone in the United States a Fair Game?”

To download for Apple:

https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/fair-game/id1138020713?mt=8

To download for Android/Google:

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.advancedhindsight.fairgame

Ask Ariely: On Ingesting Insects, Tracking Troubles, and Making Matches

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Many insects are edible, nutritious and even tasty, and they are consumed by millions of people world-wide. But when I try to eat one, I cannot get past the idea that bugs are, well, gross. Why?

—Zach

For many in the West, thinking about insects, not to mention eating one, evokes a powerful feeling of disgust. Psychologists often think about disgust as a sort of mental immune system, a deeply ingrained emotion that we have developed for evolutionary purposes to help us avoid pathogens, poisons and other pitfalls. You can even observe disgust in babies when they narrow their nostrils, constrict their lips and close their mouths while trying to expel or reduce contact with a potential contaminant.

So how could you get over your revulsion here? One option would be intensive immersion with insects. You could perhaps spend a week surrounded by pictures of them and then spend the next week locked in a room with nothing to eat but bugs.

Another less extreme option: Buy some insect powder and ask a friend to sprinkle it randomly into your meals, without your knowledge, and only tell you the next day which ones contained insects. Once you realize that the food still tasted good, your disgust should decrease.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that for many young adults, using a personal monitoring device may not help them lose weight. Should I stop using my Fitbit?

—Nati

When people start an exercise regimen, they often gain weight. The main reason: After we work out, we feel that we deserve a reward, such as a few scoops of ice cream. These extra calories can exceed those that we burn during our workout. I suspect that a similar phenomenon occurs when we wear tracking devices: We see that we’ve walked 10,000 steps or stood up 12 times during the day, and we feel justified in celebrating our amazing achievements. And of course, when we fail, we don’t feel that we need to deprive ourselves—so either way, it’s easy to wind up putting on pounds.

Still, you shouldn’t stop tracking your behavior. It is important to your health to understand when and how you become more or less active. Measurement can motivate you to become more active. And at the same time, you can work to discipline yourself not to expect a “reward” for hitting your daily targets.

You might also change the way that you measure success. What if, for example, you defined success not by making it to the gym on a particular day but by making it there on at least 80% of the days in a month—and only reward yourself when you clear that bar? If you move to such a system, I predict that tracking your health will work for you.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Like many of my friends, I love Tinder. The dating app provides a slideshow of potential romantic partners, and if two people “like” each other, Tinder tells them that they matched. How can such a simple app with so little information be so effective?

—Denise

When we think that we’re compatible with someone, we behave accordingly. A few years ago, the dating site OkCupid told users who had been rated only a 30% match for each other by the site’s algorithms that they were actually 90% matches—and these users ended up liking each other more. In Tinderland, when both people learn that they “like” one another, their expectations change, the match seems more appealing, and the power of self-fulfilling prophecy takes over.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Freelance Feedback, Teacher Tardiness, and Meal Money

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m a freelance copywriter. I like not having to hold a regular day job, but I never get performance assessments, never learn what I can do better, and never know why people stop hiring me. So to improve my performance, I’ve been thinking about sending my clients a short survey about the quality of my work. But I worry that if they’re forced to think about it, they might say, “Hmm, she’s not actually that friendly” or, “Hmm, her work is just average”—and stop hiring me. What do you think?

—Dana

Ask for the feedback. You might lose some clients in the short term, but the surveys should help you improve your work in the long term.

The trickier question is how to ask for feedback in a way that minimizes negative perceptions about your work (and maybe even spurs your clients to see your work more positively). You can do this by asking your clients to list 10 ways you could improve your work.

My guess is that your clients will easily find one or two ideas for how you could perform better, which will be useful feedback. But after that, they will find it increasingly difficult to come up with pointers until, perhaps at suggestion five, they will run out. By then, they will start thinking, “I can’t find many things wrong with this copywriter—so she must be great.” By creating the expectation that there should be 10 ways to improve your performance and having them come up well short of that, you incline them to think more positively about your work.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

At my school, in an effort to discourage teacher absenteeism and tardiness, we’ve instituted a carrot-and-stick system: Teachers gets a monetary reward if they are on time every day of the week, but if they are late on even one day, they lose a corresponding amount from their wages. Does this system make sense? Do you think it will work?

—Miriam

Yes and no. Assuming that the reward money is a substantial amount, the teachers will probably try hard to be there on time. On the other hand, since you’ve made the reward all-or-nothing (perfect attendance or a penalty), your teachers are also likely to experience the “what the hell effect.”

Imagine, for example, a teacher who was late for class on Monday. What will be his or her motivation for being on time for the rest of the week now that they’ve missed the mark on perfect attendance? Less dedicated educators may well shrug and start showing up late on purpose. I’d predict that teachers will start each week trying to be punctual, but once they slip, they’ll give up completely. You would probably be better off with a less punitive approach that is more compatible with a learning environment.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m an excellent cook who’s planning to host a gourmet, home-cooked meal for about 10 people. I’d like to use the pay-what-you-want method. So what’s the best way to ask for the money? Should I ask people to pay up front or at the end, and should it be in public or anonymous?

—Labanya

Based on the principle of reciprocity, you should ask for the money at the end of the meal (when people will know how good your food was). I would give people envelopes with their names on them at the end of the evening and ask them to put their payment inside. This way, your guests will be accountable to you but won’t know exactly how much their fellow diners paid. Have fun.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

A New Episode of Arming the Donkeys

Ask Ariely: On Honesty with Asperger’s, Adequate Achievements, and Favorable Futures

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My 19-year-old son has Asperger’s syndrome and is incapable of lying. He tends to see the world in absolutes and struggles with white lies. We have urged him to sometimes compliment people to spare their feelings, but he thinks it’s important to be brutally honest. He says, “What if you praise somebody’s ugly drawing and they then try a career as an artist? Why tell somebody that their new haircut looks great when you could warn them that they will be teased about it?” Have you looked into the ways that dishonesty may be different for those on the autism spectrum?

—Bill

I wrote a book about dishonesty and lecture frequently about it. Over the years, many parents have come to me after a talk to tell me about children who just can’t lie—and the children usually turn out to have some form of autism. Recently, I brought this up with Murali Doraiswamy, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University, who confirmed that many children on the autism spectrum do indeed have a hard time being untruthful.

This is caused, he added, by the trouble they have with what specialists in the field call “theory of mind”—that is, the basic ability to put ourselves in somebody else’s shoes and empathize with their perspective. Most of us are able to ask ourselves, “How would that person feel if I told them that their haircut is unflattering or that they smell?” Many young people with Asperger’s don’t tend to think this way, so they often don’t develop the habit of telling white lies for reasons of politeness. They don’t learn to dial down unnecessarily hurtful truths to spare another person’s feelings.

My view is that social politeness often acts as training wheels for more serious lying, so children who don’t understand white lies often don’t develop the ability to lie on a larger scale—which may not be such a bad thing. Maybe we should try a president who has Asperger’s?

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

If human beings were tools, which tools would we be?

—Kelly

The best analogy for describing human nature is a Swiss Army knife.

First, it is useful for many different tasks. Second, the Swiss Army knife gives us a lot of tools, but none of them (no offense to the Swiss) are that great. The knife is small; the screwdriver is hard to use; the can opener is OK but time-consuming to operate. And third, everything we do with a Swiss Army knife takes some time—we have to figure out which tool we want, find it, dig our nails into its little notch and yank out the desired tool.

Together, these features echo human nature: We aren’t really ideal for anything and can be a bit slow to get going, but we can do a decent job on many different challenges.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What is the most important attribute to look for in a long-term romantic partner?

—Ed

Low expectations. Much of our happiness depends on relativity—on comparing what we have with what we expected to have. In long-term relationships, we’re bound to be disappointed at some point. But if we adjusted our expectations, we might be pleasantly surprised from time to time.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like