Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A friend told me recently that wearing a bike helmet is actually more dangerous than not wearing one because those who wear a helmet take more risks, which outweighs the benefits of having their heads protected. Should I tell my kids to stop wearing helmets?

—Phil

Definitely not, but the question is a complex and interesting one. The real issues here are: what kinds of injuries helmets can prevent, how wearing a helmet alters our behavior and how our risk-taking changes over time.

Let’s think for a minute about a related case: seatbelts. When drivers, pushed by legislation, began to wear seatbelts as a matter of course, they might have felt extra-safe at first, making them think that they could get away with driving more aggressively. But after a while, as wearing a seatbelt became fairly automatic, that sensation of cocooning safety subsided. The tendency to take extra risks subsided too. So the full benefits of seatbelt use only emerged after we got used to wearing them all the time.

The same can be said about helmets. When we initially put one on, we may feel overconfident and cut more corners with road safety. But once helmet-wearing becomes a habit, we should revert to more prudent behavior, which will let us realize the helmet’s full benefits. That’s especially important, of course, with children.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m finding dating tricky these days. I’d like to show some chivalry, but it isn’t clear how to do that. Try as I might to pay the bill for dinner as a sign of respect and care, the women I’ve been out with seem to want to split it. Any advice?

—Ron

Acts of chivalry are acts of respect. They aren’t about practicality but about doing something kind for the other person. So I would suggest instead that you open the car door for your dates.

Decades ago, when car doors had to be unlocked manually, it was customary for the driver to open the door for the passenger. These days, when car locks release with a click and a beep from a keychain, doing so seems like a pointless gesture.

But that only makes it a stronger signal of chivalry: You don’t have to open your date’s door to let her in or out, but by choosing to do so, you offer a true act of consideration and caring. And it’s not only a nice gesture–it’s cheaper than picking up the tab.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why don’t people bike more? Bicycles are amazing vehicles—fast, efficient, easy to park, good for our health and our planet. What’s holding us back?

—Ziv

Simple: hills. Bicycles are fine things, and technology will no doubt continue to make them lighter, faster and safer. But all of these improvements aren’t likely to overcome our laziness—our deep-seated desire to move through the world with as little effort as possible.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

My 50th is getting closer and closer (April 29th) and because a few people have asked me over the past few days what I want for my birthday, I am walking while wondering about what makes a good gift. There are a few obvious ways to think about good gifts. Good gifts should be experiences and not things. Good gifts should be memorable. Good gifts should be unique. Good gifts should increase the social bond between the giver and the receiver. Good gifts are things that the receiver wants, but is not willing to buy for themselves. Good gifts are things that would make the receiver happy, but they don’t realize that it will.

But what are some good examples of good gifts? Headphones, Pens? Culinary classes? I would love to get examples of good gifts that you either gave or received.

And what gifts did I ask from my friends this year? I asked them not to give me anything, but I also told them that if they feel that they have to give me something, I want a copy of one of their favorite book, with an explanation why they love this book so much. And I am looking forward to having this shelf of books and reading it over the next few years.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been drinking soda for the past 15 years, and I’m trying to stop. I’ve tried phasing it out by switching to water some of the time and having a soda here and there, but I usually cave in to temptation by the end of the day. Is there a better strategy?

—Andrew

Getting off soda gradually isn’t going to be easy. Every time you resist having one, you expend some of your willpower. If you’re asking yourself whether you should have a soda whenever you’re thirsty, you’ll probably give in a lot and gulp one down.

So how can you break a habit without exposing yourself to so much temptation and depending on constant self-control to save you? Reuven Dar of Tel Aviv University and his colleagues did a clever study on this question in 2005. They compared the craving for cigarettes of Orthodox Jewish smokers on weekdays with their craving on the Sabbath, when religious law forbids them to start fires or smoke.

Intriguingly, their irritability and yearning for a smoke were lower on the Sabbath than during the week—seemingly because the demands of Sabbath observance were so ingrained that forgoing smoking felt meaningful. By contrast, not smoking on, say, Tuesday took much more willpower.

The lesson? Try making a concrete rule against drinking soda, and try to tie it to something you care deeply about—like your health or your family.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been living with a roommate for six months, and we divide up the household responsibilities pretty evenly, from paying the bills to grocery shopping. He says, however, that he feels taken for granted—that I don’t acknowledge his hard work. How can I fix this?

—C.J.

This is a pretty common problem. If you take married couples, put the spouses in separate rooms, and ask each of them what percentage of the total family work they do, the answers you get almost always add up to more than 100%.

This isn’t just because we overestimate our own efforts. It’s also because we don’t see the details of the work that the other person puts in. We tell ourselves, “I take out the trash, which is a complex task that requires expertise, finesse and an eye for detail. My spouse, on the other hand, just takes care of the bills, which is one relatively simple thing to do.”

The particulars of our own chores are clear to us, but we tend to view our partners’ labors only in terms of the outcomes. We discount their contributions because we understand them only superficially.

To deal with your roommate’s complaint, you could try changing roles from time to time to ensure that you both fully understand how much effort all the different chores entail. You also could try a simpler approach: Ask him to tell you more about everything he does for the household so that you can grasp all the components and better appreciate his work.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Is it useful to think about marriage as an investment?

—Aya

No, because the two things are profoundly different. You never want to fall in love with an investment because at some point you will want to get out of it. With a marriage, you hope never to get out of it and always to be in love.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I know that you’re turning 50 this year. How are you handling the big milestone?

—Abigail

As you can imagine, I was rather apprehensive about my 50th birthday, but I decided to embrace it and designed my year with some extra time to reflect.

In fact, I am writing to you from the sixth day of a 30-day hike along the Israel National Trail, which spans the country of my birth from Eilat to the Lebanese border. I wanted to disconnect from technology and have more time to think about what I want from life and want to do next. Six days in, checking email only late at night, I’m already in a more relaxed and contemplative mode.

I also designed the hike to help me think about earlier stages in my life. So for each day along the trail, I have invited family and old friends to join me to walk and reflect on the road behind. I’ve just finished a day of hiking with six friends from first grade, and talking about our joint history and deep friendships made me calmer than I could have imagined.

Sure, I’m a bit worried about aging. But so far, taking myself out of the usual hurly-burly and opening up space to reconnect with loved ones is proving to be an amazing antidote to the 50th blues.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

How do people recover from horrible injuries, psychological traumas and other life-altering events? Is it character or circumstances that dictate whether people crumble or rebound?

—Lionel

My sense, as someone who suffered very serious injuries as a teenager, is that the answer is both. Resilience is surely a function of one’s character and level of support, but it also has to do with the circumstances of the injury.

One of the most interesting lessons we have learned on this subject comes from Henry K. Beecher, the late physician and ethicist. In his 1956 study of pain in military veterans and civilians, Beecher showed how important it is to understand how people interpret the meaning of their injuries. These interpretations, he argued, can shape the way we experience trauma and pain.

Beecher found that veterans rated their pain less intensely than did civilians with comparable wounds. When 83% of civilians wanted to take a narcotic to manage their pain, he found, only 32% of veterans opted to do likewise.

These differences depended not on the severity of the wound but on how individuals experienced them. Veterans tended to wear injuries as a badge of honor and patriotism; civilians were more likely to see injuries just as unfortunate events that befell them. The more we interpret events as the outcome of something that we did, rather than something done to us, the better our attitude and recovery.

This lesson, while very important for traumatic injuries, also applies to the small bumps of daily life.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My relationship with my husband is going downhill, and I can’t stop thinking about it—which is putting an added strain on our marriage. What can I do?

—Rachel

Trying not to think about something is one of the best ways to ensure that you think about it constantly. If you try not to think about polar bears for the next 10 minutes, you will think more about them in those 10 minutes than you have in the past 10 years.

The same is true for your relationship with your husband. Instead of trying not to think about your marital woes, try reflecting on the good things in your relationship—then try to find activities together that will strengthen your bond. Good luck.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

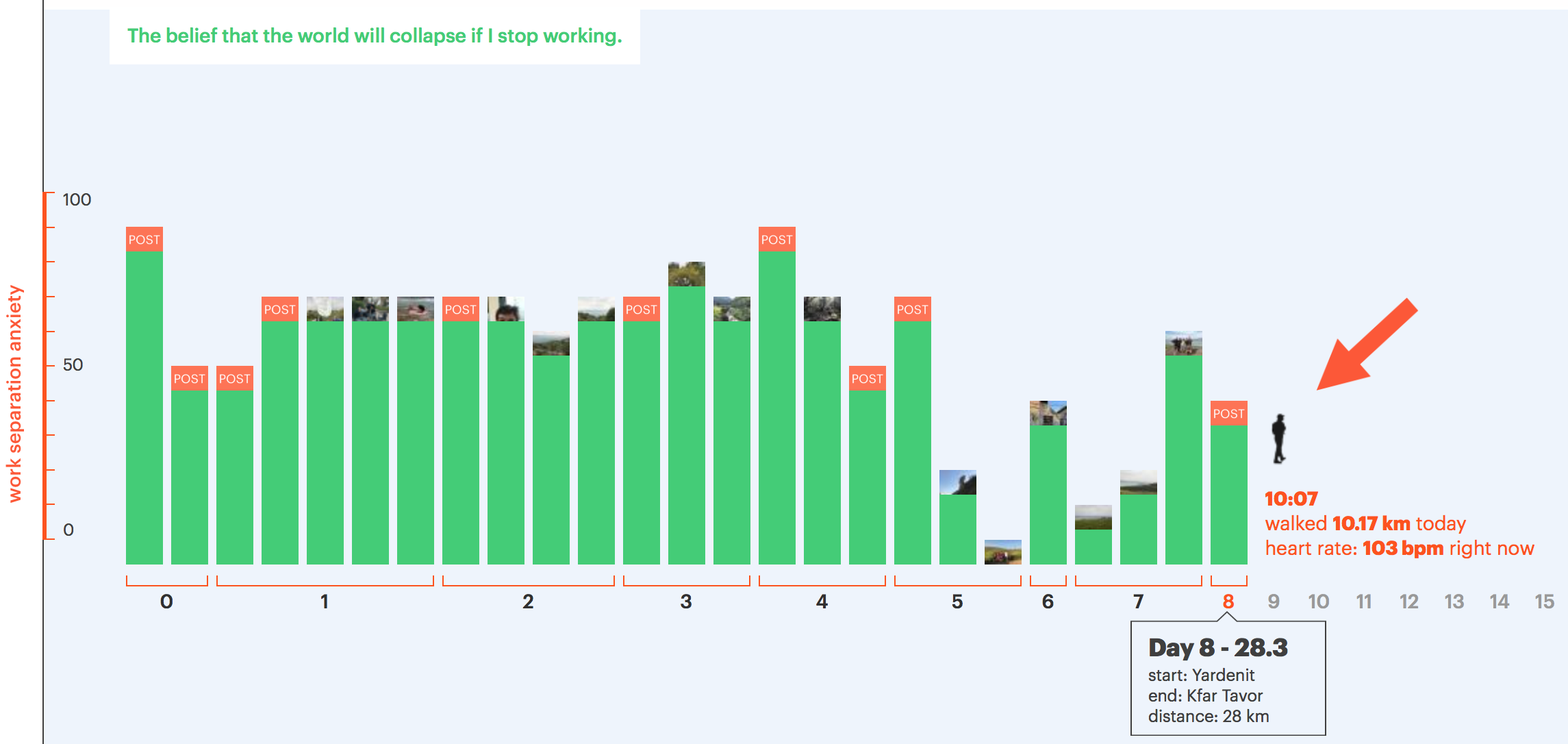

I’m just starting the second week of my month-long hike, and have been tracking some things along the way:

- Light Happiness

- Deep Happiness

- Love

- Optimism

- Regret

- Empathy

- Loving Nature

- Work Separation Anxiety

- Communication Anxiety

So far, I appear to be pretty stable on most dimensions (light happiness has taken a few dips but deep happiness is consistently high, and love/optimism/loving nature have remained high), but I’m most noticeably experiencing a downward trend on work separation anxiety. The more time I spend hiking, the less I am worrying about the growing list of tasks that would otherwise keep me up at night. It took a few days for me to get here, but my work is now taking a back seat to the importance of this trip.

I decided to embark on this adventure as an acknowledgement of my upcoming 50th birthday, and as an opportunity to reflect on life and how I want to spend the rest of it.

You can follow my journey at http://danarielyishikingtheint.com and see how the next few weeks pan out!

Irrationally Yours,

Dan Ariely

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why is it that the things that make me happy—such as watching basketball or going drinking—don’t give me a lasting feeling of contentment, while the things that feel deeply meaningful to me—such as my career or the book I’m writing—don’t give me much daily happiness? How should I divide my time between the things that make me happy and those that give me meaning?

—Vasini

Happiness comes in two varieties. The first is the simple type, when we get immediate pleasure from activities such as playing a sport, eating a good meal and so on. When you reflect on these things, you have no trouble telling yourself, “This was a good evening, and I’m happy.”

The second type of happiness is more complex and elusive. It comes from a feeling of fulfillment that might not be connected with daily happiness but is more lastingly gratifying. We experience it from such things as running a marathon, starting a new company, demonstrating for a righteous cause and so on.

Consider a marathon. An alien who arrived on Earth just in time to witness one might think, “These people are being tortured while everyone else watches. They must have done something terrible, and this is their punishment.” But we know better. Even if the individual moments of the race are painful, the overall experience can give people a more durable feeling of happiness, rooted in a sense of accomplishment, meaning and achievement.

The social psychologist Roy Baumeister and his colleagues distinguish between happiness and meaning. They see the first as satisfying our needs and wishes in the here-and-now, the latter as thinking beyond the present to express our deepest values and sense of self. Their research found, unsurprisingly, that pursuing meaning is often associated with increased stress and anxiety.

So be it. Simply pursuing the first type of happiness isn’t the way to live; we should aim to bring more of the second type of happiness into our lives, even if it won’t be as much fun every day.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently had my annual checkup, and my doctor spent maybe three minutes total with me during the visit. I know that physicians are busy, but are these quick visits the right way to go?

—James

Sadly, doctors increasingly feel pushed to move patients along as quickly as possible, like a production line. Research has shown that this approach hurts the doctor-patient relationship, which has important health implications.

Consider a 2014 study of patients who received electrical stimulation for chronic back pain, conducted by Jorge Fuentes of the University of Alberta and colleagues. They had medical professionals interact in one of two ways with their patients. Some were asked to keep their interactions short, while others were urged to ask deep questions, show empathy and speak supportively. Patients who received the rushed conversations reported higher levels of pain than those who got the deeper ones.

In other words, empathetic discussions are important for our health. Sadly, as physicians and other medical professionals become ever busier, we are shortchanging this vital part of healing.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Every year, my husband gets me a nice birthday card, but he never writes a personal note inside. Why?

—Ann

I suspect your husband overestimates the sentimental value of the words printed on the card, not realizing that they sound generic to you. Don’t judge him too harshly for this. Instead, buy one of those magnetic poetry sets and let him practice expressing himself on the fridge. Small steps.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Earlier today, a number of my blog subscribers received several automated messages for “new” blog posts, which were actually previously-published posts from the Center of Advanced Hindsight (my research lab). This was an accident that came about as I was trying to integrate the two sites. (I certainly did not intend to spam you!)

My team and I temporarily shut down the site while we identified the cause of the issue and made sure the mailing server was disabled. I am happy to report that the issue has now been resolved.

Please accept my apologies for cluttering your inbox (a topic I am extremely sensitive to). We are taking steps to ensure that this doesn’t happen again.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m one of the backers on Kickstarter of the Irrational Game, the social-science-driven card game that you developed to help us improve our “ability to predict how events might unfold.” You were late to deliver, but it came out great.

Usually, when I back something on Kickstarter, I forget about it until the product is delivered. But your team sent updates about the delays in design, testing and more. I know you intended to keep your backers informed, but the reports on these hiccups left me with the impression that you had poor foresight and management skills. Are such negative updates a bad idea?

—Lucian

You’re right on two counts. First, my planning and administrative skills need work. Second, there are real disadvantages to keeping people posted on problems with a project.

Once people decide to support a Kickstarter venture, they usually don’t think much more about it. They re-evaluate their decision only when they are reminded of it, and if the reminders are bad, they probably take an increasingly dim view of the project. So our approach turned out to be unhelpful. We often judge satisfaction by contrasting what we expect with what we get. When our backers were reminded of the game, the news was usually bad, which prompted some to sour on a pretty good project.

This would be different if the project were a big, focal undertaking for investors. In that case, they would think about it all the time anyway—which means that there would be little harm in informing them of snags that were on their minds anyway.

I must admit that, before your question, I hadn’t thought about this problem of negative reminders. I will try to be quieter next time.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I vividly remember thinking about buying Amazon stock when I was 12. I bought several stocks in my youth, but not Amazon—a mistake that has colored my entire financial future. I feel terrible regret. How do I get over it?

—Josh

Regret is a powerful motivator. We experience it when we see one thing and envisage a better, alternative reality. In your case, the contrast in realities is clear, and the thought of those imagined lost riches is making you very unhappy. Unfortunately, unless you move to some island with no internet access, you will probably keep on experiencing some of this regret with each new mention of Amazon.

The only partial cure I can suggest is trying to think about your decisions in a holistic way, paying some heed to your good decisions rather than obsessing over your bad ones. Ideally, you would take one of those wise calls and condition yourself to think about it every time you are ruing your Amazon miss.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Do ideologues, who by definition care a lot about something, lie more for their causes?

—Paula

Absolutely. Lying is always a trade-off between different values. When ideologues face a trade-off between the truth and the focus of their political passion (the idea, say, that the U.S. is an evil imperialist power or that Obamacare is a socialist plot to destroy America), they tend to be more willing to sacrifice the truth if they think it will help them to convince the idiots on the other side to do the right thing. Unfortunately, the last election suggests that more Americans have become ideologues.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like