Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have a question that has been bothering me for a very long time: Why is it that socks always get lost in the laundry?

—Jamie

This is a deep and important question, and I actually looked into it some time ago with one of my Israeli friends, Ornit Raz.

We discovered that belief in the supernatural is very strong when it comes to the disappearance of socks. Otherwise reasonable people, who think that they have a strong grasp of the forces of nature, feel at a loss when it comes to this universal mystery, and it deeply shakes their faith in the laws of physics.

We also found one mechanism that can explain this mystery—the overcounting of missing socks. You have many socks, and if you see one of them and don’t immediately find its partner, you say, “Oh! A sock has been lost!” You remember that a sock is missing, but you do not exactly recall its type or color.

Later on, you see the matching sock, but you don’t remember that it forms a pair with the first sock, and you say to yourself (again): “Another sock is missing. Where is its partner? I can’t believe so many socks go missing.”

So we often count as lost each sock in a pair—even though neither is really lost. At the end of the day, the mystery is not due to the suspension of the law of physics but to the much larger puzzle of how our memory works (or doesn’t work). Yet I still feel that, at the back of my laundry machine, there may be a black hole that is suitable just for socks.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Our daughter has been married to a bullying control freak for the past five years. We have no sympathy for her; she is an admitted gold-digger, and her hubby has boatloads of money. Knowing our feelings about the marriage, they have shut us out. My wife and I would like to see our grandson, but grandparents have no visiting privileges in our state. Any advice?

—Reg

It is hard to give advice on this complex issue, but here are a few suggestions. First, try calling your daughter and her husband and simply saying that you’re sorry about previous negative encounters. You don’t sound sorry to me, but that’s OK—just say it and say it repeatedly. In experiments, we found that saying sorry works rather well, and it works even if people don’t mean it. It works even if the person from whom you ask forgiveness knows you don’t really mean it.

The point is that, when someone says he or she was wrong and asks forgiveness, it’s hard to keep on being mad at them. You might find it hard to swallow your pride, but think about this relationship as a game of chess. You really care about the king (seeing your grandson), and pride is just a pawn in the game (well, maybe a bishop)—so it’s OK to sacrifice it.

If this approach doesn’t work, and if you’re serious about getting access to your grandson, I would recommend that you move in next door. This will force some interaction between you, and hatred is going to be harder to maintain—particularly if you are nice to your grandson (what parents can hate people who love their kids?) and if your grandson wants to spend more time with you (what parents can resist their kids?).

Finally, I should mention that my personal experience is that living next to my parents-in-law is not only incredibly helpful, meaningful and useful, but that the pleasures of an extended family have been beyond my expectations.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

With the recent debate over gun control and protecting school children, should we arm schoolteachers to make schools safer?

—Ron

Hard to know from the point of view of policy, but here’s one thing that is clear to me: If my own schoolteachers had been armed, I would not have survived middle school.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Analyst Programmer, Center for Advanced Hindsight

The Center for Advanced Hindsight is currently seeking a programmer to join our team at Duke University to develop and support a growing collection of IT tools for collecting and analyzing research data, as well as developing software that will be marketed and released to a public audience. In addition to the creation and maintenance of software, the position will provide basic IT consulting for lab members.

This position will help build and maintain a suite of fun and innovative web and mobile applications to aid in the research of helping people make better moral, financial, and health decisions. Among the projects already built is an internal iPad app that helps the Center and the Center’s collaborators around the world run new and exciting experiments on the go. While some applications will only be used internally (and the programming focus will be on functionality), others will be distributed to the public and will therefore require a greater focus on interface design and consumer usability.

Overall, the position will be responsible for programming and maintenance of applications, as well as IT support for the following:

– survey/data collection instrument design

– survey implementation across multiple mobile platforms (e.g. Android and iOS, phones and tablets)

– field-based direct data collection and quality control

– secure device and cloud server storage

– secure transmission of data using mobile platforms

To see full job description or to apply, please visit the Duke Human Resources site: http://www.hr.duke.edu/jobs/main.html and search for Req # 400718356.

a research app for smartphone scientists on the go

Social science has uncovered many fascinating aspects of human behavior, from how we think as individuals to how we act in groups. We know that humans are loss averse, emotional, habit-forming creatures. We mispredict the future and misremember the past. And yet, what social science is missing is a better understanding of how these phenomena (and others) change over time, in different cultures and regions, across gender and age.

By collecting a heaping amount of data (and increasing the size of our samples), we hope to unravel nuances in behavioral variations; we hope to detect the impact of minor differences that simply wouldn’t appear in smaller samples. The pursuit of this app is to collect an abundance of data from an abundance of locations all over the world, shining light on behavioral similarities and differences, from Antarctica to Zimbabwe. To do this, we need your help! Join our team of smartphone scientists and take on small tasks that will be “pushed” to you through the app.

On some occasions, you’ll be asked to give your opinion about various topics; you may be asked to predict the outcome of an experiment or to record your thoughts on anything from wealth distribution to peer influence. On other occasions, you’ll be sent out into the world to collect data; you may be asked to interact with a stranger or observe a scene and record certain details. Prepare to be surprised and delighted by the exciting research you will be a part of.

Participate in a movement that transcends oceans and cultural barriers, gaining access to a wider range of information than ever before. Download the app now, and get started on your first mission!

How it Works

- create an account

- complete your first mission by following the directions in the app

- sit back and wait for the next mission to be pushed to you, and make sure to complete it before time runs out!

- keep track of your missions and your points earned for each task

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I work as a waiter in Waikiki, and sometimes to pass the time I conduct mini-experiments with customers, altering my behavior and attitude from day to day and seeing if it increases tips (in case you were wondering, seeming sad nets the most tips).

I have noticed that those paying with credit cards leave bigger tips, but it varies by card: American Express users tip the most, those with Visas a little less. Discover card users are by far the worst. I can’t quite figure this out.

—V

One possibility is that wealthier people get American Express cards, the less affluent Visa, and the least well-off Discover—and they tip accordingly. You should be able to test this hypothesis by looking at their spending patterns—for example, how much they spend on wine.

Another possibility is that credit cards have a priming influence. If a person takes out an American Express card and looks at it, its reputation as a premium card might make the owner feel richer and therefore more generous. These feelings would diminish with a Visa card and be present even less with a Discover card (which generally is of more modest repute).

My guess is that both of these hypotheses play a role in what you’ve observed. To be sure, we would need to experiment by having a group of people with multiple kinds of credit cards pay in similar situations using different cards. Then we’d see if and how they change their spending.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I work with many entrepreneurs in their early innovation stage and am always intrigued by the strong (irrational) attachment they develop to their idea, often leading to their being blind to reality and to wasting time and money. How quickly do we get irrationally attached to our ideas? Is it based on elapsed time or on specific actions we take (such as presenting the idea to others)? What can be done to cure this?

—Omer

The problem, of course, is not just with entrepreneurs. From time to time we all experience someone in a meeting who says something random, and not particularly smart, but then insists that we follow up on his or her brilliant suggestion.

A few years ago, Daniel Mochon, Mike Norton and I conducted experiments about what we called “the IKEA effect”: As the instructions to build something become more challenging and complex, we love even more what we have created. We also showed that this effect takes place rather quickly. In perhaps the most interesting and irrational part of the whole story, we found out that we also mistakenly think other people will share in our excitement over our inferior creations.

What can we do about this? We could try to create an environment where ownership is less powerful or less associated with particular individuals. But if we manage to reduce or eliminate the feeling of ownership, are we also eliminating commitment and motivation? Maybe we should try to increase this sort of proprietary attachment. (And by the way, now that I have finished, I love my answer and think that it is very insightful.)

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

After I’ve bought an expensive or limited-edition scotch, I worry about drinking the bottle too quickly or being unable to find more once it’s gone. So partly opened bottles in my closet keep accumulating. Any advice on how to enjoy my scotch rather than hoarding it?

—Jonathan

The problem with hoarding (collecting) is thinking about it as one decision at a time. I would either try to think about such questions from a broader perspective (“Would I be interested in getting 24 more bottles?”) or set up a rule for the number of bottles that you can have in your house at one time (let’s say 10). Then you’d have to finish a bottle or give it away before you acquire another.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

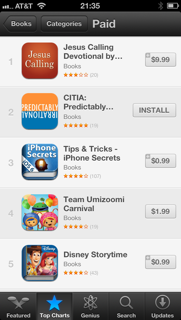

Thanks for downloading the PI app — you’ve brought it up to the #2 spot in iTunes!!

If you’d like to give the app a review in the app store, I’d very much appreciate it.

Hello friends,

This blog has turned into a great way to keep in touch with you — a persistently curious crew interested in the same Big Questions at the heart of my research: Why do we behave in the ways we do? Why do we do things that don’t always serve our best interests? What can we do to change?

As a small token of gratitude for your attention, we are dropping the price on the app edition of “Predictably Irrational” to $0.99 from now until June 7th (so, for the next 72 hours). The app offers up its own unique way to explore my research — a visual index of the book’s key ideas, with topics served up on slide-like “cards.” Makes for a neat new way to explore the book, whether you’ve already read it or not.

Irrationally yours,

Dan Ariely

Three years ago today was the publication date of “The Upside of Irrationality”

The book has 2 parts: the first is about motivation at work, and the other is about personal life (dating, happiness etc). Interestingly, in the last year I am getting much more interest from companies to do field research related to both of these domains, and this is leading to some new exciting findings on the psychology of labor and on dating….. More to come.

For now, Mazal Tov

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have worked very hard for most of my life, and I am getting to feel more secure and comfortable. But I don’t feel as happy as I expected, given all my achievements and financial success. I am not one of those hippies who think that money is not important, but it feels like something is missing. What am I doing wrong?

—Matt

Don’t worry. The fact that your financial achievements have not brought you contentment does not mean that you’re a hippie. Social scientists have long been troubled by the finding that people basically think money will bring them happiness but it does so less than they expect.

There are two possibilities: First, that money cannot buy happiness. Second, that money can buy some happiness, but people just don’t know how to use it that way. The good news is that this seems to be the correct answer.

In their fascinating book “Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending,” Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton say there are two ways to get more happiness out of our money. The first is to buy less stuff and more experiences. We buy a sofa instead of a ski trip, not taking into account that we will get used to the sofa very quickly and that it will stop being a source of happiness, while the vacation will likely stay in our minds for a long time.

Second, and more interesting, Drs. Dunn and Norton demonstrate that we just don’t give enough money away. Which of these would make you happier: buying a cup of fancy coffee for yourself, buying one for a stranger, or buying one for a good friend? Buying a cup of coffee for yourself is the worst. Buying for a stranger will linger in your mind and make you happier for a longer time, and buying for a friend is the best—it would also increase your social connection, friendship and long-run happiness.

So money can buy happiness—if we use it right.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m going to an out-of-town concert next month with friends and, as usual, I ended up organizing everything, booking a hotel room and fronting the money. When I’ve done this with groups in the past, I always end up spending the most on shared expenses, because they are never divided up evenly.

Perhaps I’m afraid to ask for large amounts of money, even though these are the true expenses that should be shared by everybody. What can I do to make sure that the bill for this upcoming show is split fairly?

—Scott

This is a question, in part, of how much you care about splitting the expenses evenly and how much responsibility you’re willing to take to improve the situation. I assume you’re willing to take this responsibility, so I suggest that you collect money from everyone in advance and pay all bills from this pool of money (and add 20% just in case, because we often don’t take all contingencies into account).

This way, everyone will pay the same amount, and bill-splitting will never come up. If there’s extra money, keep it for next year, or buy everyone a small gift to better remember the vacation.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have sometimes found myself walking behind a woman at night in an unsafe place and going in the same direction. Even though there is some distance between us, I can feel the doubt and worry in her mind. How do I handle this situation? Should I stop or say something? I have places to be, too, but clearly I don’t want the woman to feel unsafe.

—Steve

Simply pick up your cell phone and call your mother. In the world of suspicion, nobody who calls his mother at night could be considered a negative individual.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

You know the pain of making a bad money decision, from small to large—remember that Living Social deal you never used, or the big house you thought you needed that turned out to be a money pit? Sure you do! But most of us don’t know how to spend money in a way that actually makes us happy, aside from the rush of novelty that quickly dissipates as the hedonic treadmill continues on. Well, allow me to present a new book from my friends Mike Norton and Liz Dunn, which will help you do exactly that. This is not your typical CPA make-and-save-money advice—this lays out well-researched advice for how to spend money in a way that improves your life as a whole. Who couldn’t use that?

In the mean time, here’s an Arming the Donkeys interview I had with Mike on this very topic.

Enjoy, and Happy Reading!

Do you remember Segway, that odd, upright, (and sometimes dangerous) electric scooter? Pundits once predicted the Segway would revolutionize personal transportation and reduce American oil dependency. As it turns out, these days, it is used either by corny tour groups in large cities or it’s been relegated to the object of sight gags and physical comedy, from “Arrested Development” to “Paul Blart: Mall Cop.”

After examining Google’s latest product, Google Glass, it is hard not to question whether it is ready for the market. With a design reminiscent of the “Terminator” films and a preliminary price tag of $1,500, Glass risks being the biggest flop since Segway if Google doesn’t learn from Segway’s mistakes.

The Segway failed, not because of poor engineering, but because of poor attention to consumer psychology. Similarly, Google Glass might be functional from an engineering point of view, but does it have the form necessary to generating mass-market appeal? To this point, it looks like the tech giant is trying to avoid these “Segway barriers,” but as consumer psychologists, we have few suggestions for Google.

Psychological principles that suggest why Google may succeed

1. Form and function combined create positive feelings for consumers.

Segway had functionality, but its form lacked elegance. As a result, Segway was unable to shed its awkward image. In its current form, Glass is more like the nerdy Segway than the sleek iPhone. Google seems to be making efforts to streamline, or “de-geek,” its new product by hiring experts to redesign it.

Until Google is ready to launch a redesigned Glass, the company’s ad campaigns center on attractive models. This technique invites consumers to associate Glass with the positive feelings evoked when we look at attractive people.

2. The more effort we put into acquiring a product, the more we tend to value and enjoy that product.

To determine who would test the first version of Glass, Google held the “Glass Explorer” competition, in which applicants submitted Twitter entries with the hashtag, “#ifihadglass”. Winners were given the “privilege” to buy Glass for $1,500. By participating in the contest, consumers became mentally and emotionally invested in Glass. This led to “effort justification,” meaning that those who expend more effort to get the product and then pay for it come to value it more.

As a bonus for Google, all this effort demonstrates to interested observers that Glass is valuable. This type of user exclusivity plays on scarcity, a psychological hot button that ultimately makes Glass more desirable.

How Google can improve its marketing strategy for Glass

Even with the efforts Google has already undertaken to ensure that Glass won’t flop, we offer a few further suggestions to help guarantee a successful launch.

1. Create advertising campaigns that appeal broadly to normal people.

So far, marketing for Glass seems to center on young hipster techies in urban environments, but if Glass is going to succeed, Google needs to make ads that depict average people doing normal things. Granted, Google may be working to develop Glass’s “cool factor” before proving its functionality, but they will need to focus on the average consumer if Glass is going to sell big.

2. Get people to try on Glass.

If people see themselves using a product, they are more likely to buy it. There are also lingering questions about Glass that Google must address. How should consumers use the product? Is Glass something we wear all the time? What if we already wear glasses? Glass doesn’t make immediate sense in most of our lives: do we really need another gadget, given the proliferation of tablet computers and smartphones? To help consumers understand its functions and purposes, Google should have people try on Glass. Past research shows that consumers are more likely to buy products when they have the opportunity to test them. Testing a product may not improve its “cool factor,” but it certainly helps us imagine using the product in real life.

CONCLUSION:

Google may be playing a long-term game with Glass, focusing on engineering first, followed by coolness, before setting their sights on breaking into other markets – something Apple did before it exploded. Even if this is their strategy, Google should make sure to foreground the psychology of design. Otherwise Glass will go the way of the Segway, at medium speed into closet of cobwebs or, worse yet, end up used primarily by groups of ironic hipsters going on “urban tours.”

~Rachel Anderson and Troy Campbell~

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like