Having a college degree can dramatically increase a young adult’s income. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2014 the median earnings of young adults (ages 25-34) with a bachelor’s degree were 66 percent higher ($49,900) than the median earnings of young adults with only high school diplomas ($30,000).

Anyone who performs well in high school can apply to college, and there are many scholarships, financial aid, and other support programs available to help make college an option for everyone. But does this help?

Topic 4 in Fair Game? asked users to think about whether household income is related to the likelihood of getting a college degree and what that relationship should look like in a fair world.

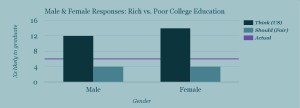

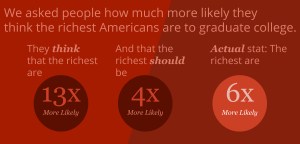

On the whole, our users estimated that the wealthiest 25% of society would be 13x more likely to get a college degree than the poorest 25%. In reality, the wealthiest 25% are about 6x more likely to get a college degree.*

How much more likely do people think the wealthy should be to get a college degree, in a fair world? 4x more likely.

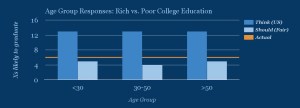

Estimates for the greater likelihood of getting a college degree were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair. There may be hints of a difference in what people think is fair, with 30-50 year-olds reporting 4x likelihood, while other age groups said a 5x likelihood would be fair. One possible explanation for this difference is that people in the 30-50 age range may be actively planning or paying for their children’s college expenses.

What about gender? Males and females differ in their estimates of the greater likelihood of getting a college degree for the top 25% of income, estimating 12 and 14 times greater likelihoods, respectively. But they agree in what they think a fair likelihood would be — 4x.

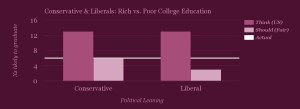

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal estimate the same (13x) greater likelihood of getting a college degree for the wealthy. In terms of how much more likely the top 25% of income should be to get a degree, in a fair society, conservatives answered 6x more likely and liberals answered 3x more likely. So although their understanding of the world is similar, their notions of fairness, for this topic, are very different.

Together, the data reported here suggest that people overestimate the gap in the likelihood of getting a college degree. And they would reduce the size of the gap that they perceive. There are many factors that contribute to the gaps in attainment of a college degree. Family income based factors are certainly an important contributor. But there are also decisions about whether to apply to college at all, what type of college to attend (e.g. for profit vs. nonprofit), how to access and pay back loans, and what kind of support a student may have from their social networks. Sometimes, just the paperwork involved in applying to college can overburden a prospective student and derail the process. It is encouraging then that low-cost interventions have the potential to improve college opportunities for low-income students.

Given the potential economic benefits that would result from more low-income students getting a degree, what are other possibilities that might work to increase the proportion who ultimately do get a degree?

What do you think? Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m having trouble waking up in the morning. I set my alarm clock, but I always wind up hitting the snooze button or turning it off completely. Any advice? If I want to wake up at 7 a.m., what time should I set my alarm for, and how many times should I hit snooze?

—Phillip

Set your alarm for exactly the time you need to get up. Since you want to start your day at 7, you may be tempted to set the alarm a bit early (let’s say 6:40) and hit snooze a few times until it is 7 or maybe even 7:15. But if you pick this snooze strategy, your body can’t learn the conditioned response between hearing the alarm and getting up.

In general, our bodies do better when they can get used to a single clear rule: Get out of bed the moment the alarm sounds. When we play with the snooze button, our bodies get a confused message: Sometimes we hear the beeping and get up, sometimes we hear it and stay put for 10 more minutes, sometimes we lie there for another 20 minutes, and so on.

So just bite the bullet and get out of bed when the alarm tells you to. Do this faithfully for a few months, and the conditioning should start to kick in. It won’t be fun in the beginning, but over time, it should pay off. Good luck.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When I’m out for dinner, I occasionally encounter a wine so special that I buy a case of it to drink at home. But the subsequent bottles never taste as appealing as the initial one, so I wind up not only regretting the purchase of additional wine but also spoiling some of the wonderful memories of my night at the restaurant.

So why can’t I enjoy the same wine as much at home? Is there something special about the way the restaurant handles the wine or the glow of the original occasion?

—Eugene

After an excellent dinner out, we might remember the wine as impeccable. But we probably won’t realize that part of our enjoyment of the wine flowed from the flickering candles, the beautiful music, the tasty food and the charming company. At home, the same wine is just the wine, without the halo effect, and it isn’t the same experience. Psychologists call this phenomenon the “misattribution of emotions”: We assume that the source of our enjoyment is one thing when it is really another.

It’s almost never possible to revisit special experiences. The place where you spent your honeymoon, for example, probably won’t make a good family vacation spot: A few days of chasing the kids and trying to eke out a few hours of sleep will certainly taint (if not erase) the original memory.

Next time, enjoy the wine, commit the whole experience to memory, don’t try to relive it, and look forward to new experiences.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently started using a smartphone app to manage my to-do list, and I’m really enjoying it. Every night, I take some time to make my to-do list; every morning, I go over it; and as I tackle different tasks throughout the day, I check them off my list. I feel not only more organized but more productive. Is there good documentation about an increase in productivity from to-do lists?

—Lev

You might be experiencing some increase in real productivity, but my guess is that you are mostly experiencing “structured procrastination.” That is the feeling of productivity that we get from making lists and crossing things off them—which spurs us to spend time on things that make us feel productive rather than on being productive. I am not recommending that you stop using this app, but I hope that you will measure your productivity based on what you’re getting done in your real-life projects, not on racking up checkmarks.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Hey everyone, I hope this blog post finds you well. Recently, I wrote a short paper about trust….

The paper, Trust Factory, discusses elements of trust; specifically regarding the way organizations can interact with individuals to build trust. If you’re interested in reading the paper, you can view this link.

The paper talks about how humans tend to trust one another. But does it work the same way when it comes to trusting organizations?

A community of trust is required to survive. That’s what trust is based on.

Understanding that, what can organizations do to gain the trust of their consumers/users? I outline five key tools that allow us to trust each other: long-term relationships, transparency, intentionality, revenge and aligned incentives.

View the paper by clicking on this link.

Trustfully yours,

Dan

Confronting our mortality is not an easy task for most people. However, there are many reasons people should consider just how long they might live.

In the case of retirement planning, life expectancy is important in relation to the benefits like Medicare and Social Security that people earn during their working years. According to the Pew Research Center, use of these government benefits programs is “virtually universal (97%) among those ages 65 and older—the age at which most adults qualify for Social Security and Medicare benefits.”

Differences in life expectancy between the rich and the poor can mean that more affluent Americans receive hundreds of thousands of dollars more in benefits that those who are less well off. In addition to the economic considerations, there is a psychological and perhaps even moral factor that comes into play when thinking about how long we might expect to live in relation to our financial status.

Topic 3 in Fair Game? asked users to think about exactly this question and to estimate how income is related to life expectancy and what that relationship should be in a fair world.

“It will surprise nobody to learn that life expectancy increases with income.”— Michael Specter, 4/16/16, The New Yorker

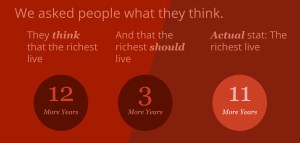

On the whole, our users estimated that the richest 10% of society would have a life expectancy 12 years longer than the poorest 10%. In reality, the difference is 11 years (12 additional years for men and 10.1 additional years for women).

How many more years of life do they think the wealthy should expect in a fair world? 3 more years (a 75% reduction from their estimate of what is true).

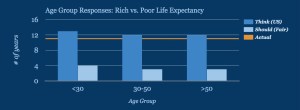

Estimates for the current difference in life expectancy were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair. Preferences for a fair difference were also similar. There may be hints of a difference between younger and older adults, with a possible explanation simply being ‘mortality salience’, or how much longer users themselves’ expect to live.

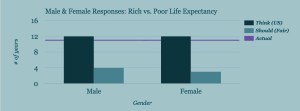

What about gender? Both males and females estimate 12 more years of life for the top 10%. But they differ slightly in what they think a fair amount of additional years would be — 4 vs. 3, respectively.

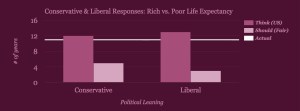

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal only differed by 1 year in terms of what they believed the life expectancy gain from wealth to be, and 2 years in what they thought it should be in a fair world. Conservatives estimate the gain to be 12 years, while liberals put it at 13 years. In terms of what they think would happen in a fair society, conservatives consider 5 years and liberals consider 3 years to be a fair number of years gained with wealth. Despite these small differences, the presumed improvement (from what is thought to what it should be) ends up being 7 years for conservatives vs. 10 years for liberals.

Together, the data reported here suggest that estimations of the present gap in life expectancy are fairly accurate. And that small differences in life expectancy (3-5 years) are considered fair (or perhaps tolerable) by most people. Has the wealth-based life expectancy gap always been this large? According to a Brookings report, it has actually grown from 4.5 years (for the cohort of seniors born in 1920) to 11 years (for the cohort born in 1940). It is likely that multiple factors, including differential access to quality medical care, and higher rates of smoking and obesity, contribute to the growth of this gap. On top of all of this, wealthier people typically retire later and can delay receiving social security payments, thereby increasing income inequality in the older population.

Unfortunately, public benefits that were originally intended to be progressive seem to be becoming (unintentionally) regressive over time. Perhaps there are some solutions that might help to keep more Americans living long, happy, and healthy lives?

What do you think? Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

Have you ever had a burning curiosity or a puzzling life dilemma? Each week, many people write to my Ask Ariely column for guidance – and I’ve now created an app to help disseminate some of their questions and my advice.

If you’ve ever wondered what to eat when you’re heartbroken, how to effectively raise money for a charity, why you’re so willing to buy expensive beer, or why people tend to think God shares their beliefs, this app is for you.

Responding to people’s curiosities is one of my favorite parts of being a behavioral economist and researcher. I hope to share my enjoyment with you in this app, which features bite-sized excerpts from my latest book, Irrationally Yours, for easy reading.

The app is live now, available for Android and iOS users alike.

Happy reading,

—Dan

It’s a simple statement but it represents so much more than just four words. For many people, it is a rallying call for closing the gap between men’s and women’s wages, ultimately achieving the goal of pay equity, and protecting a notion of basic fairness.

Others question the very idea of what equal work means, with some people arguing that women make different career choices compared to men and that any gap is merely a reflection of those choices. But in the United States, there are many historical examples of inequality affecting women including: denial of property rights, the right to vote, the ability to obtain higher education, and barriers to particular occupations and specialized careers.

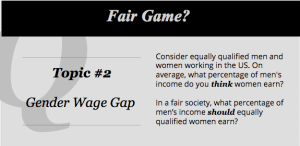

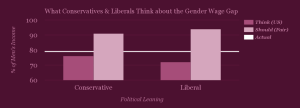

Given the complex history of women’s equality in the U.S., we wanted to find out what people think about the current state of working women and their pay relative to men. We focused on the gender wage gap for topic 2 of Fair Game?, our new app that asks users what they think about the world as it is today and what they would want in a fair world.

Surprisingly, people tend to overestimate the gender wage gap and believe women earn 73% of men’s income. In reality, women are estimated to earn 79% of men’s income.

How much do people think women should be paid in a fair world? 93% of men’s income.

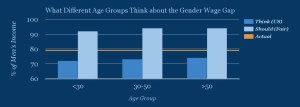

Overall, responses did not dramatically differ by the age of the user.

How does your own gender relate to what you think about this? Male and female users both overestimated the magnitude of the gender wage gap, with men thinking women currently earn 74% of men’s salaries, and women estimating that they earn 70% of men’s salaries.

There was closer agreement for the question of what a fair wage gap should be, with males preferring 93% and females preferring 94% of men’s salaries. On the whole, both genders perceive a gap to exist in the United States and would substantially – but not completely – close that gap in a fair society.

And can we observe differences in views according to political beliefs? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal only differed by 4% in terms of what they believed the gender wage gap to be, and 3% in what they thought it should be in a fair world. Conservatives estimate women’s salaries to be 76% of men’s, while liberals put that percentage at 72%. In terms of what they think would happen in a fair society, conservatives consider 91% and liberals consider 94% to be a fair ratio of women’s to men’s income. Despite these relatively small differences, on average, the increase in women’s salary thought to yield fairness would be 15% for conservatives vs. 22% for liberals.

The gender wage gap is a topic that deserves careful consideration. Although a single number represents an average for all women, the number varies substantially once we consider factors including race, age, education, profession, career trajectory, childbirth status, and U.S. state of residence, to name a few.

There is also likely to be some gender role stereotyping at play in the results we received, with many of our respondents probably assuming that the burden of childcare would or should fall disproportionately on women.

This is a complex topic, but we can learn from some efforts to equalize opportunities in the workplace for women. A program in the Canadian province of Quebec provided an interesting natural experiment, demonstrating that subsidized daycare could support an upsurge in employment of women that in turn boosted economic output to a level that more than paid for the childcare subsidy costs1.

A final consideration is how long it will take to close the gender wage gap, given the progress that has already been made. One measure of improvement (the upward trend since the 1960’s), predicts the gap to close by 2059. But if a recent slowdown in the trend persists, the gap would not close until 2152. What other efforts do you think might be worthwhile to pursue to help close this gap, sooner or later?

And please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

- Fortin, Pierre et al. (2012). Impact of Quebec’s Universal Low-Fee Childcare Program on Female Labour Force Participation, Domestic Income and Government Budgets. Sherbrooke: Research Chair in Taxation and Public Finance, University of Sherbrooke.

Inequality is an important topic and one that politicians and scholars spend a lot of time thinking about. But what does the general public think about inequality and the many ways it manifests in daily life? And how do factors like age, gender, or political leanings relate to our views on inequality?

Those are the questions we are exploring with Fair Game?, our new app that asks users what they think about the world as it is today and what they would want in a fair world.

We’re asking users about 13 different topics related to inequality, from wage gaps to opportunities for education, and will be sharing our findings every few days now through mid-November.

Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play. We’ll release a new question every few days until we get through all 13.

You can think about the first topic right now.

So far, the data show a consistent knowledge gap.

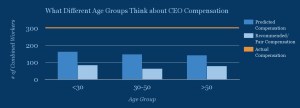

Our users estimate that the average CEO’s pay is equal to 151 average worker salaries. In reality, the average CEO makes the same as 303 average workers combined. What do people think CEOs should be paid in a fair world: the same as 72 average employees combined.

We also found some interesting patterns in what people think.

Younger people estimate the ratio of CEO pay to average worker pay to be larger than others do, and also think a larger ratio is fair. Perhaps younger people have lower salaries and therefore think the average worker’s salary is lower? Or they are looking ahead to larger, CEO-like salaries in the future, and that influences what they think is fair?

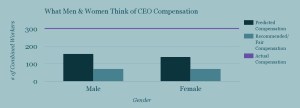

What about gender?

It is notable that males and females arrive at the same number for what would be fair (72 average worker salaries for each CEO), but differ in what they think currently exists in the world (158 for males vs. 140 for females). Perhaps the gender wage gap influences the perception of what salaries are in the world?

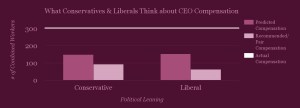

And political leaning?

People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal give similar estimates of what the current CEO to average worker salary is (149:1 and 152:1, respectively). But political leaning makes a big difference in what people think what would be fair. Liberal respondents believe 63:1 would be fair, whereas conservative respondents believe that 93:1 would be fair.

It is encouraging that political leaning does not dramatically change our respondents’ perceptions of the world. Both conservatives and liberals underestimate the magnitude of executive pay relative to worker pay in the United States. But their differing assessments of what would be fair suggests that conservatives and liberals might choose different approaches to reducing the executive-to-worker pay ratio.

Executive compensation is by no means a simple issue. In fact, the 2016 Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to researchers who considered how motivational factors should be related to pay, bonuses, stock compensation and the timeframe of company performance in order to achieve optimal levels. One of the winners, Bengt Holmström, told a reporter after hearing he had won, that he thought executive bonuses were “extraordinarily high” and compensation contracts were too complicated.

Has it always been like this? The ratio of executive pay to worker pay was 20-to-1 in 1965, when CEOs earned an average of $832,000 annually, compared to $40,200 for workers (adjusted for today’s dollars). In 2000, the number peaked at 376-to-1, and has since settled back down to the recent level of 303-to-1 (and some estimates are as low as 216-to-1). This increased ratio means that CEO compensation has risen dramatically over the past few decades, but the average worker compensation has not. In 2014 the average CEO made $16,316,000 compared to the $53,200 made by the average worker.

In an effort to promote greater transparency, the Securities and Exchange Commission will soon require every publicly traded company in the United States to disclose this ratio. A recent bill proposed in the California Senate calls for instituting a sliding scale of corporate taxation, with companies paying different tax rates based on their ratios and sharper increases for those with CEO to average worker pay ratios greater than 100-to-1. Other proposals for reducing the ratio and social ramifications of large gaps in companies include greater profit-sharing across employees and a more consistent relationship between (long-term) performance and bonuses.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My wife and I recently had our first child. We know that friends and family, especially grandparents, like to buy gifts for children for birthdays and holidays. But we have set up a college savings account for our child and would much prefer to have our loved ones put money into this account rather than buy things that our child doesn’t really need. How can we encourage this more rational behavior?

—Kyle

Though giving money is often more economically efficient than giving stuff, the feeling of social connection that we get from gift-giving is higher when we give something tangible. If I were you, I would try to provide the gift-givers with a chance to do a bit of both. You can ask them to buy something small for your child and also to put some money in the college fund.

If you want an even higher proportion of the money to go to the college fund, buy a nice book with blank pages and on its cover write your child’s name and the word “future” (“Dan’s Future,” for example). You can then ask each gift-giver to put money in the college fund and, at the same time, to share some advice for life by writing on one page of the book. This way, there will be a physical reminder of their gift (the book and the advice), but more of the money will go to the college fund.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am trying to stop using Facebook because it only wastes my time and makes me feel bad about myself. But despite repeated attempts to stay away from my Facebook page, I keep coming back to it. I think part of the reason is that I’m so impulsive. Do you have any advice on how I might finally break my Facebook habit?

—Maryam

My recommendation is to create some sort of “Ulysses contract.” As you will recall from Homer’s ancient tale, Ulysses knew that if he allowed himself to hear the tempting calls of the Sirens, he would follow them and in the process kill himself and his crew. So he asked his sailors to tie him to the mast of his ship and put wax in their own ears. Ulysses thus protected himself from temptation by making it impossible to take action when temptation appeared. He didn’t have to summon his willpower to resist.

Maybe you can make your own Ulysses contract by asking a friend to change your Facebook password and not to tell you what it is for a month. This will give you a chance to see what life without Facebook feels like and to decide if that is indeed what you want. If it is, you can then go ahead and delete your account—and you will be free of Facebook.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I hate waiting for anything. I get very impatient when I have to wait for food in a restaurant, for my new iPhone, for the next time I will meet a good friend, etc. Is there anything I can do to make it less painful to wait?

—Maya

Sometimes anticipation can be a pleasurable part of the experience. Imagine, for example, that you could get a kiss from your favorite movie star. Would you rather get the kiss in the next 30 seconds or in a week? When faced with this question, most people prefer to wait because, in the end, a kiss is just a kiss, but waiting for a unique kiss can be wonderful. My advice is that you try to get into such a mindset for other experiences as well, and instead of thinking about waiting as a delay, think about it as an opportunity for anticipation.

P.S. I got this question from you a few months ago, and I hope that you enjoyed anticipating my response.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

At the Startup Lab (my incubator at Duke University’s Center for Advanced Hindsight), we aim to empower early stage startups to build better consumer health and finance products by teaching them how to apply both the findings and methods of behavioral economics to their products and business models.

While the in-depth Startup Lab program is limited to a small group of startups that go through our rigorous application process, it would be an injustice to not share some of its lessons with the greater community. So I’ve collaborated with +Acumen to create an online course to help social entrepreneurs make an impact – by designing products that change consumer behaviors for good. But what I am most excited about is the lesson on experimentation. I am always getting questions about how startups can experiment within their small companies (with few resources, especially time), and this course provides the tools for entrepreneurs to take a systematic approach to experimentation.

While the in-depth Startup Lab program is limited to a small group of startups that go through our rigorous application process, it would be an injustice to not share some of its lessons with the greater community. So I’ve collaborated with +Acumen to create an online course to help social entrepreneurs make an impact – by designing products that change consumer behaviors for good. But what I am most excited about is the lesson on experimentation. I am always getting questions about how startups can experiment within their small companies (with few resources, especially time), and this course provides the tools for entrepreneurs to take a systematic approach to experimentation.

Sign up for my Master Class with +Acumen on Changing Customer Behavior, now available here: http://bit.ly/2e11cOZ

What is fair?

According to Merriam-Webster:

: agreeing with what is thought to be right or acceptable

: treating people in a way that does not favor some over others

: not too harsh or critical

Many people can tell you when something is NOT fair (especially children, who test this concept more thoroughly than any scientist could)! Injustice may be an easier phenomenon to spot in the world (especially when we are the victim or perceived victim).

Does society view what is right or acceptable through a single lens, or does an individual’s unique background and experience shape their perception of fairness? In our new app, you can join in by answering questions about aspects of life in the United States. Do you think the world that we live in is fair? What should the world look like? Give your opinions and be a part of this large-scale social expression. You may learn something about yourself and about society. And you’ll help us answer the question, “Is life for everyone in the United States a Fair Game?”

To download for Apple:

https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/fair-game/id1138020713?mt=8

To download for Android/Google:

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.advancedhindsight.fairgame

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like