Higher Education, Higher Incomes…Opportunity for all?

Having a college degree can dramatically increase a young adult’s income. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2014 the median earnings of young adults (ages 25-34) with a bachelor’s degree were 66 percent higher ($49,900) than the median earnings of young adults with only high school diplomas ($30,000).

Anyone who performs well in high school can apply to college, and there are many scholarships, financial aid, and other support programs available to help make college an option for everyone. But does this help?

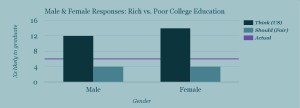

Topic 4 in Fair Game? asked users to think about whether household income is related to the likelihood of getting a college degree and what that relationship should look like in a fair world.

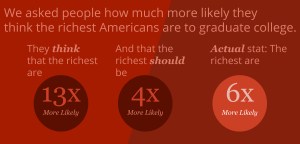

On the whole, our users estimated that the wealthiest 25% of society would be 13x more likely to get a college degree than the poorest 25%. In reality, the wealthiest 25% are about 6x more likely to get a college degree.*

How much more likely do people think the wealthy should be to get a college degree, in a fair world? 4x more likely.

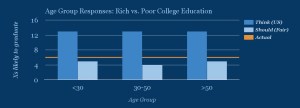

Estimates for the greater likelihood of getting a college degree were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair. There may be hints of a difference in what people think is fair, with 30-50 year-olds reporting 4x likelihood, while other age groups said a 5x likelihood would be fair. One possible explanation for this difference is that people in the 30-50 age range may be actively planning or paying for their children’s college expenses.

What about gender? Males and females differ in their estimates of the greater likelihood of getting a college degree for the top 25% of income, estimating 12 and 14 times greater likelihoods, respectively. But they agree in what they think a fair likelihood would be — 4x.

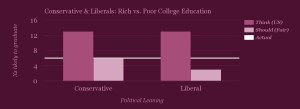

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal estimate the same (13x) greater likelihood of getting a college degree for the wealthy. In terms of how much more likely the top 25% of income should be to get a degree, in a fair society, conservatives answered 6x more likely and liberals answered 3x more likely. So although their understanding of the world is similar, their notions of fairness, for this topic, are very different.

Together, the data reported here suggest that people overestimate the gap in the likelihood of getting a college degree. And they would reduce the size of the gap that they perceive. There are many factors that contribute to the gaps in attainment of a college degree. Family income based factors are certainly an important contributor. But there are also decisions about whether to apply to college at all, what type of college to attend (e.g. for profit vs. nonprofit), how to access and pay back loans, and what kind of support a student may have from their social networks. Sometimes, just the paperwork involved in applying to college can overburden a prospective student and derail the process. It is encouraging then that low-cost interventions have the potential to improve college opportunities for low-income students.

Given the potential economic benefits that would result from more low-income students getting a degree, what are other possibilities that might work to increase the proportion who ultimately do get a degree?

What do you think? Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

The Trust Factory

Hey everyone, I hope this blog post finds you well. Recently, I wrote a short paper about trust….

The paper, Trust Factory, discusses elements of trust; specifically regarding the way organizations can interact with individuals to build trust. If you’re interested in reading the paper, you can view this link.

The paper talks about how humans tend to trust one another. But does it work the same way when it comes to trusting organizations?

A community of trust is required to survive. That’s what trust is based on.

Understanding that, what can organizations do to gain the trust of their consumers/users? I outline five key tools that allow us to trust each other: long-term relationships, transparency, intentionality, revenge and aligned incentives.

View the paper by clicking on this link.

Trustfully yours,

Dan

Life (and the Pursuit of Happiness)– But for How Long?

Confronting our mortality is not an easy task for most people. However, there are many reasons people should consider just how long they might live.

In the case of retirement planning, life expectancy is important in relation to the benefits like Medicare and Social Security that people earn during their working years. According to the Pew Research Center, use of these government benefits programs is “virtually universal (97%) among those ages 65 and older—the age at which most adults qualify for Social Security and Medicare benefits.”

Differences in life expectancy between the rich and the poor can mean that more affluent Americans receive hundreds of thousands of dollars more in benefits that those who are less well off. In addition to the economic considerations, there is a psychological and perhaps even moral factor that comes into play when thinking about how long we might expect to live in relation to our financial status.

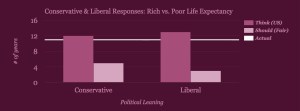

Topic 3 in Fair Game? asked users to think about exactly this question and to estimate how income is related to life expectancy and what that relationship should be in a fair world.

“It will surprise nobody to learn that life expectancy increases with income.”— Michael Specter, 4/16/16, The New Yorker

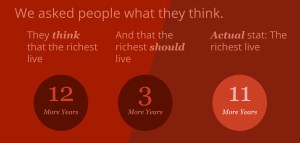

On the whole, our users estimated that the richest 10% of society would have a life expectancy 12 years longer than the poorest 10%. In reality, the difference is 11 years (12 additional years for men and 10.1 additional years for women).

How many more years of life do they think the wealthy should expect in a fair world? 3 more years (a 75% reduction from their estimate of what is true).

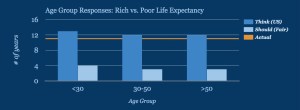

Estimates for the current difference in life expectancy were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair. Preferences for a fair difference were also similar. There may be hints of a difference between younger and older adults, with a possible explanation simply being ‘mortality salience’, or how much longer users themselves’ expect to live.

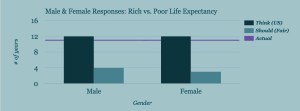

What about gender? Both males and females estimate 12 more years of life for the top 10%. But they differ slightly in what they think a fair amount of additional years would be — 4 vs. 3, respectively.

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal only differed by 1 year in terms of what they believed the life expectancy gain from wealth to be, and 2 years in what they thought it should be in a fair world. Conservatives estimate the gain to be 12 years, while liberals put it at 13 years. In terms of what they think would happen in a fair society, conservatives consider 5 years and liberals consider 3 years to be a fair number of years gained with wealth. Despite these small differences, the presumed improvement (from what is thought to what it should be) ends up being 7 years for conservatives vs. 10 years for liberals.

Together, the data reported here suggest that estimations of the present gap in life expectancy are fairly accurate. And that small differences in life expectancy (3-5 years) are considered fair (or perhaps tolerable) by most people. Has the wealth-based life expectancy gap always been this large? According to a Brookings report, it has actually grown from 4.5 years (for the cohort of seniors born in 1920) to 11 years (for the cohort born in 1940). It is likely that multiple factors, including differential access to quality medical care, and higher rates of smoking and obesity, contribute to the growth of this gap. On top of all of this, wealthier people typically retire later and can delay receiving social security payments, thereby increasing income inequality in the older population.

Unfortunately, public benefits that were originally intended to be progressive seem to be becoming (unintentionally) regressive over time. Perhaps there are some solutions that might help to keep more Americans living long, happy, and healthy lives?

What do you think? Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

New World Bank Initiative to Tackle Human Relationships

WASHINGTON, DC, USA, March 30, 2016

After decades of attempting to tackle some of the world’s most challenging problems, such as poverty, conflict, and economic mismanagement, the World Bank announced today that it will now tackle the principal cause of human misery.

Under the leadership of the Bank’s president Jim Yong Kim and the Bank’s new Global INsights Initiative (GINI), the World Bank’s analytics have become more penetrating and its operational agenda far more daring.

“We are excited by the opportunity to address the root cause of the world’s greatest conflicts,” said Kim, the bank’s president. “People, and how they just can’t get along.”

Fractured relationships have been increasing monotonically for several decades. The frequency of marital fights, rising divorce rates, and the substantial increase in short term relationships – facilitated by apps such as Tinder – make this initiative a necessary next step for the Bank and the world, claims Varun Gauri, who is the lead for the new task force.

“Within five years,” said Gauri, “The team will provide a definitive answer to why couples fight so much.”

This five-year initiative will include educating the public in various topics pertaining to effective relationships, piloting different family structure arrangements, and conducting randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of new marriage contracts. Among the many topics that the task force is expected to study are: Teen dating decisions (i.e. who to date, who not to date, how to roll your eyes at your parents advice), timing marriages, correct strategies for marital fights (i.e. how to argue effectively, things to fight about, how to make sure the couch is comfortable after those fights), money management in the home, techniques for effective and productive makeup sex, and how to properly raise children.

There will be a social accountability component in which individuals dissatisfied with their marriages will be able to call the World Bank. There will also be a worldwide dating app on the World Bank website.

“It is not as if men are really from Mars and women from Venus,” said Kim. “But let’s just say that when men try to meet women halfway, on Earth, they usually get lost and don’t stop to ask for directions.”

The initiative is being supported by a $38.2 million grant from the Hallmark Corporation a $7 million grant from the Gates foundation, and a $20.7 million grant from the Swedish government.

“Everyone who’s ever been in a relationship agrees that this is a very good use of resources,” added Gauri. “They say money can’t buy you love, but it can help us figure out why it’s so hard to make relationship work.”

The World Bank plans to complete this initiative by the year 2021.

Announcing… CAH Startup Lab

Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University

Beginning with the 2015 academic year, the Center for Advanced Hindsight (CAH) at Duke University will invite promising startups to join its behavioral lab and leverage academic research in their business models. The Center is housed within the Social Science Research Institute at Duke University and is led by Professor Dan Ariely, Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Economics at Duke University. The Center studies how and why people make counterintuitive or irrational decisions and works to translate this academic research into easily applicable lessons that are accessible to all. A key goal of the Center is to explore new research directions and to translate academic research into accessible tools for better decision-making. To further this goal, the Center is looking for entrepreneurs and startups interested in applying social science research findings to their business in order to build decision-making tools primarily in the areas of financial decisions and health decisions.

The Startup Lab at CAH

Beginning in the fall of 2015, the Center will select several for-profit and/or not-profit startup companies interested in building digital solutions that address decision behavior in the health and finance fields. During an incubation period of 6-9 months, the Center’s researchers will help participants leverage social science research to test and bring to scale innovations aimed at substantially improving decision-making in the health and finance fields.

The Startup Lab will offer:

- Technical Assistance – Participants will learn to apply a behavioral lens to the design of their products and services and will learn to rigorously test each phase of iteration using proven methods.

- Mentorship – Participants will gain access to mentors from several schools at Duke University including the Fuqua School of Business and the Pratt School of Engineering.

- Financial Assistance – Participants will be given office space/equipment and will be provided with an internal operating budget.

- Networking Opportunities – Participants will gain access to Duke-connected resources such as the Duke Angel Network connecting alumni investors with Duke-affiliated startups. They will also become part of Durham’s growing entrepreneurial community, which has already established itself as a rich environment for accelerator and incubator programs.

Eligibility Requirements

We will select several domestic and/or international startups, consisting of about three or four participants each. Participants must be willing to relocate to our location in Durham, North Carolina for a period of 6-9 months beginning in the fall of 2015. Participants do not have to be U.S. citizens, however, non-US citizens that have participated in a J-Visa program within the 24 months preceding the start date of our program will be ineligible to apply.

Application Process

To apply, please provide a written summary of the problem you are addressing and how far along your startup currently is both in terms of development and funding. Please also describe what you hope to gain from the program and provide links to your LinkedIn profiles. Email your application to Rebecca Kelley at rrk9@duke.edu.

The application deadline is July 1, 2015, and offers will be extended in late July. The program will begin October 1, 2015 and run for 6-9 months depending upon the needs of the applicants.

Enjoy Summer Movies with a Childlike Wonder Again

With the summer movie season officially starting with The Amazing Spiderman 2 (Though arguably it started this year early with Captain America), it’s time once again to enjoy big budget spectacle movies. But as adults sometimes it can be hard to feel the movie magic we felt as children. Don’t fret! Here are a few tips (inspired by research in consumer psychology) on how to enjoy movies with a childlike wonder.

#1 As a kid you had more time for movies. So as an adult, you need to make a little extra time.

When adults see movies, they might talk about the movie for a few minutes afterwards. If they are true nerds, maybe they read a blog or two. But that’s about it. The movie experience starts the night they see it and ends that very same night.

For a kid, the experience doesn’t end when the movie ends. Instead, the movie is an invitation into years of immersion into a fictional world. Kids talk nonstop about movies, force their parents to take them to Toys R Us to buy the action figures, and then expand on those stories through play, reading, fan websites, and video games.

The Fix:

You should make the time to get more involved with a movie world. How “good” you find a movie, can be affected by how much effort you put into it. This means reading blogs about movies and watching the behind the scenes features on the DVDs.

#2 Kids are encouraged to be excited about movies. So, as an adult you need to find friends that encourage that same excitement.

Not only do kids feel a sense of wonder with movies, but they are also encouraged to embrace that sense of wonder. Parents encourage their children to tell them about the things they love. No one encourages adults to talk about movies. The guy in the office next to me has explicitly made it clear that he doesn’t want to hear any more about the awesomeness of The Empire Strikes Back.

This is unfortunate, because the suppression of expression is terrible for enjoyment. Professor Sarah Moore of the Alberta School of Business finds when people explain exciting things in a boring way, they end up finding the content boring. But if they explain it in an exciting way, they magnify their enjoyment. The conclusion: if people do not express their passion with strong emotion, they may lose out on some of the passion.

The Fix:

If you want to enjoy movies more, put on a costume and attend a convention where nerd passion is socially encouraged. Or have a Katherine Heigl movie night if that’s more your thing. Or at the very least just post about a movie on Facebook and start a discussion. The point is, if you share your passion with others you can maintain and grow your passion.

#3 As a kid, everything was magical and new. So, as an adult, you need to find new things.

Remember how impressed you were as a kid by that quarter behind the ear trick? Today you find that completely unimpressive — at least hopefully you do.

The next time you are even slightly impressed by an action movie, think how impressed a kid would be. Kids love things so easily that they probably even thought X-Men Origins: Wolverine was cool.

Scientists find that when people become overexposed to content (e.g., a type of fight scene), our brains stop paying as much attention. Once something is no longer new, our brains tell us to check out, so the joy starts to fade away.

The Fix:

Adults should branch out and start watching slightly “odder” content – I suggest the indie monster film Monsters or a Wes Anderson film. Adults won’t be desensitized to the new type of content, so they’ll likely find more magic and wonder in it. Or, try a more intense movie experience like The Wolf of Wall Street.

#4 Nostalgia is why we love our childhood movies. So as adults we need to create more instantaneous nostalgia.

Nostalgia gets a bad rap publicly. However, nostalgia is a very powerful feeling, and there are many positive reasons to spend some quality time indulging in nostalgia.

The great thing about nostalgia is that nostalgic memories tend to be linked to memories of social connections. For instance people’s memories of Star Wars are wrapped up in memories of their parents showing it to them for the first time or playing “Rebels vs. Empire” with their friends. These connected memories bring about the feelings of warmth, support, and love that fulfill humans’ greatest needs.

You might even think that movies from your childhood were terrible, but love those movies nonetheless. You love those movies because they have meaning to you. The emotional connections and meanings are sometimes more important to you than the quality of the film.

The Fix:

If you want to enjoy modern movies more, you need to make movie-going become more instantaneously nostalgic. So go see the films in big groups. Start a Sunday afternoon movie crew or go to a midnight showing. Again, if you want to enjoy something, you need to change the process by which you enjoy it to make it bigger, more memorable, and more full of social interactions with other fans.

So, next time you go to the movies, see if you can bring back some of the magic from your childhood. Try a new genre of movie, talk about it with your friends after, or just put a little more effort into really enjoying the experience. You may not be a child any more, but with these tips in mind, you just might be able to enjoy the movies like one.

~ Troy Campbell ~

5 Steps to Improving Your Understanding of Behavioral Economics

Today, many individuals, governments and businesses are eager to use behavioral economics to improve lives, happiness, and profits. So, how can one get a good beginning handle on behavioral economics? Reading up and taking a class can never substitute for years of education in the topic, but taking these five steps can help improve your general thinking, help you better communicate with behavioral experts, and help you develop an experimental mindset.

So what is behavioral economics? (A quick run down)

Behavioral economics, or behavioral sciences, applied psychology, business psychology, decision making, or whatever title you prefer, is the study of human irrationality, decision making, self-control, and emotions.

This past year has served as a symbolic victory for the field. Daniel Kahneman, widely considered the founder of the field, released the book Thinking, Fast and Slow and won the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in America, to go along with his International Nobel Prize. The United States government also opened a “Behavioral Insights” team with the goal of integrating behavioral research into government policy.

Behavioral science is becoming a staple in business and public policy. Energy companies use social comparison with neighbors to reduce energy consumption and businesses help people “save more tomorrow” by having them commit to automatic enrollment in the future. Rather than just assuming that people will save energy and manage their retirement with perfect rationality, behavioral economics accepts and defends the idea that people will not always be motivated by rationality or cash alone. Instead, it examines what actually motivates people.

Alright, so most likely you don’t have time to hire your own private behavioral insights team. So, what can you do? Here’s how to improve your understanding a little bit.

#1 Accept that humans are irrational.

In his book Critical Decisions, behavioral scientist Peter Ubel concludes that humans are neither completely rational nor completely irrational, but argues that people attempt to understand others logically far too often.

In his book Critical Decisions, behavioral scientist Peter Ubel concludes that humans are neither completely rational nor completely irrational, but argues that people attempt to understand others logically far too often.

For instance, how many times have you tried to logically argue with a friend or co-worker? Did it go well? Probably not. Why? Because logic does not exclusively dictate human behavior. Emotions, self-control, and a person’s life history greatly influence behavior.

One big takeaway from behavioral science is that we must continually consider factors other than rationality that can influence people’s behavior. So step one: remember people are irrational and that logic alone will rarely win the day.

#2 Think about your own psychological quirks.

One of the best ways for us to recognize irrational behavior in others is to first recognize it in ourselves.

One of the best ways for us to recognize irrational behavior in others is to first recognize it in ourselves.

You may have noticed that you tend to be less rational when you’re tired. You may have noticed that you sometimes act with prejudice. For instance, just think of the last time you saw someone wearing a jersey from an opposing sports team. Did you automatically assume negative things of them? Understanding how you, (presumably) a good and sane person, can commit errors in judgment will allow you to see, understand, and empathize with others’ all too human behavior.

Starting to understand patterns of irrationality or imperfect decision-making can help you understand people’s “predictable irrationalities” – the ways in which people act predictably like humans rather than rational perfect machines.

#3 Watch science on TED.com.

TED.com has a collection of behavioral economics talks, which are great for understanding the mindset of a behavioral scientist. The talks cover topics such as how to think about happiness, memory, honesty, or decision-making. Start with talks by Rory Sutherland, Daniel Kahneman, or the Center for Advanced Hindsight captain, Dan Ariely, and you will start to get into the mindset. From there, click the related videos. After a couple hours of those videos, you will be ready for some reading.

TED.com has a collection of behavioral economics talks, which are great for understanding the mindset of a behavioral scientist. The talks cover topics such as how to think about happiness, memory, honesty, or decision-making. Start with talks by Rory Sutherland, Daniel Kahneman, or the Center for Advanced Hindsight captain, Dan Ariely, and you will start to get into the mindset. From there, click the related videos. After a couple hours of those videos, you will be ready for some reading.

#4 Starting reading. And here’s what to start with.

Books – To begin, start with a hit from the behavioral sciences such as Thinking, Fast and Slow or Predictably Irrational. Books with fantastic prose from authors like Malcolm Gladwell are good to check out, but it is best to start with a book that intensely focuses on the research. This will help you build a solid foundation.

Books – To begin, start with a hit from the behavioral sciences such as Thinking, Fast and Slow or Predictably Irrational. Books with fantastic prose from authors like Malcolm Gladwell are good to check out, but it is best to start with a book that intensely focuses on the research. This will help you build a solid foundation.

Online – Next follow a blog or twitter account from at least one of these behavioral experts: @Nudgeblog, @DanTGilbert, or @RorySutherland (there’s lots more but these are three random ones to give you a good start). By following the experts, you may also have access to occasional live twitter conversations between them — another entertaining way to learn. And, of course, follow the lab @advncdhindsight and @DanAriely.

Local – Locate professors at your local university who conduct behavioral economics, social psychology, or decision-making research. Follow their blogs, check out their university talks, and even get some face time with them at local events. Academics are generally pretty open, so go spend time with them!

#5: How to read. – This one is important!

Do not binge and forget. Instead, spread out your reading. Due to the availability bias in human reasoning, things that you learn and even know deep in your memory may not be “on top of the mind.” Just because you learned something once doesn’t mean you’ll be in the state of mind to always use that knowledge.

Do not binge and forget. Instead, spread out your reading. Due to the availability bias in human reasoning, things that you learn and even know deep in your memory may not be “on top of the mind.” Just because you learned something once doesn’t mean you’ll be in the state of mind to always use that knowledge.

Reading a little but often keeps behavioral economics on the top of your mind. So, when you encounter a situation where someone is acting odd, the behavioral economist inside of you will always be primed and ready to interpret the situation.

A final reminder

However, we remind you that even a person with Ph.D in behavioral economics can’t always predict what exactly will happen. Science is about consist using hindsight to improve foresight. Not matter how much advanced hindsight you’ve paid attention to life, there can never be enough. That’s why it is also important to always put your hypotheses to a test. If your in a business try an experiment or use online survey polls (e.g. Mechanical Turk) to get some initial data or feedback. Thinking like a scientist means being comfortable with the fact you don’t know everything.

Those who realize how much they don’t know will end up knowing the most.

Announcing the 2014 Summer Internship In Behavioral Economics!

Real-world Endowment

One of economists’ common critiques of the study of behavioral economics is the reliance on college students as a subject pool. The argument is that this population’s lack of real-world experience (like paying taxes, investing in stock, buying a house) makes them another kind of people, one that conceptualizes their decisions in altogether different ways. And although many decision-making studies in behavioral economics have shown that young adults do not act much differently than adult adults when it comes down to their core behavior (think of MDs whose diagnoses are influenced by defaults and the framing of choices, for example), the argument persists as a sweeping dismissal of using students as the main testing ground.

One area where we can test this assumption is with the endowment effect. Simply put, the endowment effect shows that we value the things we own more than identical products that we don’t own. This causes a mismatch between buyers and sellers, where buyers are often willing to spend less than the seller deems an acceptable price.

If we are to assume that consumers hold constant, well-defined preferences, this puts the stability of valuations into question. As such, the endowment effect has puzzled economists for quite some time because in principle, valuations should not be affected by ownership; if a purple hat is worth $15 to you, it should be worth $15 to you whether or not you have purchased it, and this value should remain consistent both before and after you purchase it.

Let’s say that undergraduate A receives a mug and is asked how much money she would require to sell it to undergraduate B. Studies find that undergraduate A will have a much harder time parting with the very same mug that undergraduate B has no attachment to. Now, these students don’t have much experience with real-world markets. So the question is — would those who do have experience in these markets behave differently than their inexperienced undergraduate counterparts?

In his senior research paper, Sean Tamm studied exactly this*. He approached 30 car salespeople and 46 realtors, a population that presumably has much experience with negotiating their maximum willingness to accept (when selling items), as well as with a maximum willingness to pay (when purchasing items). He endowed half of these participants with mugs, and asked the sellers what it would take to sell the mugs and the buyers what it would take to buy the mugs. And despite the extensive real-world market experience of these participants, willingness to accept was about three times higher than willingness to pay, demonstrating that even expert negotiators are susceptible to the endowment effect. This is consistent with previous research, showing an overvaluation of owned goods of about 2.5 times that of unowned goods.

This is just one more example of real-world experience not playing the protective role that we often assume comes with experience. It also suggests that our brains and the way we make decisions are similar, and that for the most part, students are operating under the same constraints as those with much more experience. In the end, we may just have to accept that students are real people (most of the time).

*“Can Real Market Experience Eliminate the Endowment Effect?” by Sean Tamm, Stetson University

Swiss Army People

Plato once said that people are like dirt. They can nourish you or stunt your growth. This seems sage and reasonable, but I think people are more like Swiss Army knives (To be fair, Plato did not have the benefit of knowing of such a tool, so I don’t think I’m detracting from his comparison in the least). Swiss Army knives, as we all know, are incredibly versatile, and have a tool for almost any situation. Need to open a package—it’s got a knife! Sharing beers with friends on the beach—it’s got an opener! Have something in your teeth—there’s a toothpick for that! Need to do a little electrical work—it’s a got a tool that can strip wires! The downside is that Swiss Army knives are not particularly good for any specific purpose because any really intricate task is going to require much more specific tools.

People are a lot like Swiss Army knives from this perspective, and I am saying this with tremendous appreciation. A lot of the research in behavioral economists criticizes people for various ineptitudes: why we don’t save money, why we don’t exercise, why we text and drive. And it’s true, there’s a lot to criticize and a lot that goes wrong in our decision-making processes, but when you consider just how versatile we are, it’s very impressive. Essentially, we do a lot of things sort of OK. We can reason moderately well about money, we’re often pretty good with various relationships, we’re fairly moral, and most of the time we don’t kill ourselves or others. Not bad if you think about it this way!

Now, some people are more like the specialty tools, like post hole diggers, or lemon zesters, or cigar cutters; in these cases these individuals are truly excellent in certain domains. But often these people aren’t the best at navigating the world in a pragmatic fashion. There are often savants, like Kim Peek (the person that Rain Man is based on), who certainly can’t handle the day-to-day on their own, but have extraordinary abilities in other spheres. And plenty of geniuses have similar problems; take Bobby Fischer’s statelessness and detentions, or van Gogh’s famously self-detrimental tendencies and ultimate suicide. If everyone were like these folks, our species would surely be in peril. If people were all specialized, and could only think numerically, or long-term, or probabilistically, what would life be like? Neither rich nor long.

Of course these people provide inspiration and spur progress, and we admire and celebrate many of them (who don’t put their genius to antisocial use), but we should be grateful that most of us are more like Swiss Army knives.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like