Ask Ariely: On Pleasing Presents and Sympathizing Sibling

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My aunt gave me some money for my birthday. Since she wasn’t sure about my likes and dislikes, she said to spend it on something that would make me happy. Do you have any advice on how to choose?

—Katy

While I’m sure there are many items that would make you happy, spending the money on someone else could make you even happier. In an experiment, researchers gave participants either $5 or $20. They then randomly asked the participants to go about their day and spend that money either on themselves or on someone else. Later, the researchers asked them about their happiness. Those who had spent the money on someone else, regardless of the amount, reported feeling happier throughout the day.

But what to buy these other people in order to get both the glow from gift-giving and something that they will like? A different set of researchers asked people to name the last gift that they had received and say how happy they were with it.

Though gift recipients were happy with items that they had wanted, on average they were even happier with unexpected and surprising gifts. These made them appreciate the thought from the sender and got them to experience something new. Hopefully your aunt will also appreciate how you choose to spend her gift money.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My sister is one of my closest friends, and she’s usually one of the first people I call when I need solid advice or someone to talk to. Our lives, however, are pretty different, and they are starting to differ more. Sometimes I hesitate to open up and ask for her advice because I’m not sure she can relate to what I’m going through. What should I do? Should I look for someone else to get feedback and advice from?

—Ingrid

It’s reasonable to think that it is best for someone to have “been there” in order to understand you and give you good advice. Indeed, a recent survey found that people predicted that a shared experience would lead to greater insights. But is that true?

In one experiment, participants listened to a short video describing a negative emotional experience. They were asked to analyze how the storyteller was feeling about the experience and also indicate if they had a similar story from their own past. The results showed that listeners who had a negative experience in common with a storyteller were much less accurate at describing how the storyteller felt.

It may be that people were more likely to focus on their own similar experience if they had one, which shifted their focus away from how the storyteller was feeling. These results suggest that even though someone has “been there,” they might not understand how you’re feeling in the moment you most need support.

So while your sister might not be going through the same things as you, that doesn’t mean she can’t empathize. In fact, her distance from your exact situation—but closeness with you—might give her a perspective nobody else can offer. Stick with your sister.

Ask Ariely: On Regret over Rental, Guns under Control, and Dishes with Friends

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

On a recent trip, the car-rental agency offered me insurance that cost almost as much as the rental itself. I ended up taking it, but when I got the credit-card bill, I couldn’t understand what I’d been thinking. Why do we buy these things?

—Benjamin

It has to do with counterfactual thinking and regret. Imagine that you take the same route home from work every day. One day, along the usual route, a tree falls and totals your car. Naturally, you’d feel bad about the loss of the car—but you’d feel much worse if, on that particular day, you had tried a shortcut and, with the same bad luck, come across the car-wrecking tree. In the first case, you’d be upset, but in the shortcut case, you’d also feel regret about taking that different route.

The same principle applies to car rentals. When a rental agent offers us pricey insurance, we start imagining how stupid and regretful we’d feel if we skipped it and (God forbid) had an accident. Our desire to avoid feeling this way makes us much more interested in the insurance.

Now, it probably is OK to pay a bit more to avoid remorse from time to time—but when the price tag gets large, we should start looking for ways to cope more directly with our feelings of regret.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m wondering what you make of gun control. Obviously, it is in everyone’s best interest to have a safer country where you’re less likely to be shot in public. But since the massacre in Oregon, gun sales have only gone up. Is there anything we can do to reduce gun violence?

—Skyler

This all strikes me as a case of over-optimism. When we hear about gun violence, we tell ourselves, “If I didn’t have a gun, I might get attacked—but if I had a gun, I could protect myself.” We can imagine the benefits of gun ownership, but we can’t imagine the stress or panic we’d feel while being attacked. (In wartime, in fact, many guns never get fired because of the stress felt by people under fire.) We also can’t imagine ourselves as hotheaded attackers or imagine our new gun being used by people in our household to attack others.

After all, we’re such good, reasonable people, and those surrounding us are similarly upstanding and calm. So people buy guns, often with good intentions—but these guns make it easy for someone having a moment of anger, hate or weakness to do something truly devastating.

Since humanity will keep having emotional outbursts, what can we do to lessen gun violence? One approach would be to try to make it less likely that we will make mistakes under the influence of emotions. When we set rules for driving, we’re very clear about when and how cars can be used, which involves heeding the speed limit, obeying traffic rules and so on. Maybe we should also set up strict rules for guns that will make it clear when and under what conditions guns can be carried and used. And we could require gun owners to get licenses and training—again, on the model of car safety—with penalties for breaking the rules.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When my chore-hating kids visit their friends, they clear their dishes and help in the kitchen. How can I get them to do that at home?

—Jon

Like many of us, kids are motivated by the impressions they make on people they care about. Clearly (and sadly), you aren’t on that list. Maybe you can get one of those home cameras, connect it to your kids’ Facebook feeds and observe the power of impression management as they try to impress their friends.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

New book: Happy Money.

You know the pain of making a bad money decision, from small to large—remember that Living Social deal you never used, or the big house you thought you needed that turned out to be a money pit? Sure you do! But most of us don’t know how to spend money in a way that actually makes us happy, aside from the rush of novelty that quickly dissipates as the hedonic treadmill continues on. Well, allow me to present a new book from my friends Mike Norton and Liz Dunn, which will help you do exactly that. This is not your typical CPA make-and-save-money advice—this lays out well-researched advice for how to spend money in a way that improves your life as a whole. Who couldn’t use that?

In the mean time, here’s an Arming the Donkeys interview I had with Mike on this very topic.

Enjoy, and Happy Reading!

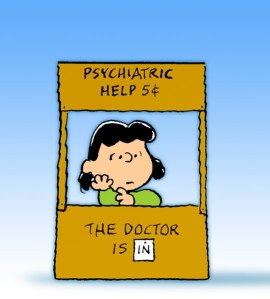

Advice Column

Starting next week, the doctor is in! I’m teaming up with The Wall Street Journal to offer answers to readers’ questions sent to IdeasMarket@wsj.com. Whether it’s about family matters, work conundrums, in-law issues, or where to take your next vacation, I’m happy to have the chance to let you sprawl out on my e-couch and provide some (hopefully useful) advice. And it won’t cost you a dime. Or a nickel.

The Facebook IPO: A Note to Mark Zuckerberg; or, With “Friends” Like Morgan Stanley, Who Needs Enemies?

I just received this letter from a friend in the banking industry. He prefers to remain anonymous (you’ll see why soon enough).

Dear Mark,

There’s been a lot of ballyhoo recently about your IPO and your choice of investment bankers. Indeed, a war was fought by the banks to win your “deal of the decade.” As reported in the press, the competition was so intense banks slashed their fees in order to win your business. Facebook is “only” paying a 1% “commission” for its IPO rather than the 3% typically charged by the banks.

Congratulations, Mr. Zuckerberg! On the surface it appears your pals in investment banking have given you a quite a deal!… Or have they?

Let’s take a closer look and see what you’re getting for your money.

To start, your bankers have the task of selling 388 million Facebook shares to the public. In return, these banks will receive $150 million for their efforts. Morgan Stanley will get the largest share of that amount—approximately $45 million. But is $45 million all that Morgan Stanley makes off your deal?

Before we answer this question, let’s first dissect the sales pitch that Morgan Stanley probably gave you to justify “only” the $150 million fee. We’ll look at what they told you, and then what that actually means.

1) We will raise the optimal amount of money for the company, for our 1% fee. (Translation: How great is it that Zuckerberg believes he got a great deal by getting us down to a 1% fee! We can’t believe he got hoodwinked into agreeing to any level of what are actually variable commission fees.)

2) The definition of a successful deal is having a good price “pop” on the first day of trading. This will make all parties happy and you, Mark, look like a rock star. (Translation: No one benefits more than us if Facebook’s share price rises significantly on day one. That first day price “pop” will take money directly out of your pocket and puts it in ours and those of our “best friends”—not yours or the public stockholders. We will, at almost all costs, make this happen.)

3) This is a very complicated process, especially for such a large company, but we are here to successfully guide you through it. (Translation: It actually takes the same amount of work to do a large IPO as a small one. Thus for approximately the same amount of work we’re doing for Facebook, we sometimes get only $10 million—$140 million less than we’re making on Zuckerberg’s IPO.)

4) We will perform due diligence on your company to make sure the business and its finances are as they seem. (Translation: While it certainly does take some time and effort to perform reasonable due diligence, Facebook is a very large and well-known company, and we have done this same procedure hundreds of times.)

5) We will write a prospectus that outlines Facebook’s strategy, business plan, financials, and risks, and we will get it approved by the SEC. (Translation: Per the regulatory guidelines, a prospectus is largely a boilerplate document; for the most part, it’s just a lot of cutting and pasting.)

6) Once this prospectus is completed and with input from the Facebook team, we will come up with “the range” or the approximate price we think your IPO shares should be sold at to the fund managers. (Translation: The price of your IPO will be determined by where and how we can best optimize our (secret) profits on the deal.)

7) We believe the best shareholders are large fund managers, as they will become long-term holders of Facebook stock. However, at your request, we will allocate 25% of the IPO shares to sell to individual investors. (Translation: There are 835 million Facebook users worldwide. One could argue that what is best for Facebook would be to let all of Facebook’s legally eligible customers enter orders to buy Facebook stock. Then through the broker of their choosing, they could enter the quantity of shares they want to buy and the price they want to pay, just like the fund managers do—or are supposed to do. More on this scenario below.)

8) Our 10-day sales process will begin. For this important “road show,” you will be introduced to our large fund manager clients. These fund managers will receive our pitch for why they should buy your stock, and we will assess their interest and at what price. (Translation: Far from being long-term holders, many of our large fund manager “best friends” will, as soon as Facebook shares start trading, sell (or “flip”) for a windfall profit on all the underpriced shares we’ve given them. We’ll enable this by creating a perceived “feeding frenzy” for the stock by putting out an artificially low initial estimate ($28 to $35 per share) for where we think the IPO will be priced. We will then raise that estimate during the road show. Rumors about this begin to circulate over the next day or so.)

9) At the end of the road show on the night before the IPO, we will review the overall supply and demand for the stock and then “price” the shares. This is the price at which the large fund managers will receive their “winning” Facebook shares. (Translation: The price of the stock is already known. For the past few years, Facebook shares have been actively trading on such venues as SecondMarket and SharePost.)

10) And finally, we will put a mechanism, called a Greenshoe, in place that “supports” your share price after the IPO. (Translation: Thank God Zuckerberg doesn’t understand one of the greatest investment banking profit enhancing creations of all time—“The Greenshoe.” The Greenshoe will likely be our most profitable part of this deal. It’s a secret windfall, and although we market it to Facebook as a method to stabilize its share price, it’s really just another way for us, with little effort, to make huge amounts of money.)

We’re not done yet, Mark. Now, I’d like to dig a bit deeper into what’s going to happen and show you all the additional ways your banker friends and their large fund manager clients are going to make oodles of money off your deal.

1) Morgan Stanley only gives Facebook shares (“golden tickets”) to their best client “friends.” In other words, it’s no coincidence that Morgan Stanley’s biggest fund manager clients get the bulk of the shares offered in this kind of deal.

2) How do you become best friends with Morgan Stanley? There are lots of ways, such as trading tens of millions of shares with them or using the firm as your prime broker.

3) I’m sure there are a lot of conversations going on right now between Morgan Stanley’s salespeople and their clients. These conversations are probably along the lines of (wink-wink) “before we allocate our Facebook shares, we’d like to ask first if you plan to do more trading with us over the next week to six months….”

4) Let’s assume that 50 of Morgan Stanley’s “best friends” trade an extra 2 million shares so they can get access to more shares of the Facebook IPO. Let’s also assume that the average commission these clients pay to Morgan Stanley is 2 cents per share. Well, those extra trades will dump an additional $2 million dollars into Morgan’s coffers.

5) Now comes the part where Morgan Stanley actually gives free money to its friends. If the Facebook IPO is like the majority of other recent Internet offerings, here’s what Morgan Stanley will likely do. They know Facebook will be a “hot” deal. Especially, with all of the “5% orders” coming in, there will be huge demand for Facebook shares. My prediction is that Morgan Stanley will “price” Facebook at approximately $40 per share. This is the price at which Morgan Stanley’s “best friends will be able to buy the bulk of the 388 million shares offered.

6) Now let’s now assume that Facebook shares open for trading at $50—a lower percentage premium than Groupon’s opening share-price “pop.”

7) Let’s assume that one of Morgan Stanley’s “best friends” decides to sell 3 million shares right after the opening at $50 per share. That “best friend” will instantaneously make a $30 million profit. That’s right, a $30 million profit.

8) Here’s a question for you Mark. If Morgan Stanley’s “best friends” are selling Facebook shares at $50, who’s buying them? The answer is your “friends,” individual investors, most of whom are your customers.

9) Now for the final insult—the Greenshoe. Technically speaking, the Greenshoe gives your investment banks a 30-day option to purchase up to 15% more stock from Facebook than was registered and sold in the IPO. In layman’s terms, this means that, over the next 30 days, your “best friends” at the investment banks are able to buy approximately 50 million of your shares at $40 per share.

10) As in our example above, let’s say Facebook shares do trade at $50 soon after the IPO. Now I am a simple person, but if I were given the opportunity to buy something at $40 that I could immediately sell at $50, I would do it all day, every day…. And so will the investment banks. The Greenshoe actually gives these banks the ability to do this for 50 million of your shares.

11) So let’s assume that Morgan Stanley and its other banking “friends” buy 50 million shares at $40 per share and then sell these shares at $50. Morgan Stanley and its banking “friends” will make an additional $500 million- yes, $500 million- a HALF BILLION DOLLARS off your company.

So let’s now do a tally to see how much money all of your banking friends are going to make just for the privilege of doing your IPO. Let’s also see where this money comes from.

“Discounted” fees/commission: $150 million

Greenshoe profits: about $500 million

Extra trading commissions from large fund managers: approximately $10 million

—————

Investment Bank Profits: $660 million

As the lead bank on your deal, Morgan Stanley is likely to get 30% of the overall take. This means that your closest investment banking “friend” will make a bit more than $200 million from your IPO.

Morgan Stanley and the rest of the investment banks involved will also make sure that their favorite fund manager client “friends” are given lots of free money. Assuming that these “friends” are given 75% of the total number of IPO shares, or a total of 291 million shares, and assuming that the stock does rise from $40 to $50, then these fund managers will collectively, in one day, make $2.9 billion dollars in realized or unrealized profits. That’s right, 2.9 BILLION DOLLARS.

Mark, by now you must be asking yourself the obvious question. “Where and out of whose pocket does this money come from?”

Well, just think of it this way… Let’s assume you own a very expensive piece of waterfront real estate, and you hire a broker to sell it for you. After exploring the market and after getting indications of interest, your broker advises you that $10 million would be a great price for your home. You meet with the potential buyers and decide to sell it for $10 million. After the $1 million commission you have to pay your broker, your net proceeds are $9 million. An hour later, you drive by the house and see your broker in the driveway shaking hands with some different people. You pull over to see what’s going on, and you find that the people you just sold the house to for $10 million are very close friends of your broker. To your dismay, you also find out that those friends just sold your (former) house to somebody else for $15 million.

The same exact game is going on here, Mark. You’ll be selling 388 million shares of Facebook stock in your IPO. A likely scenario is that your broker “friends” are telling you to sell your shares at $40 per share. You’ll take their advice and sell at $40 per share, and the buyers will be Morgan Stanley’s biggest fund management clients. By the time you drive around the block, these folks will have sold their shares at $50 per share. In other words, using the same real estate scenario, you’ll have sold something of yours for $15 billion that is really worth $19 billion. And for that “unique” privilege, you’ll be paying your “friends” at the banks $150 million as a fee.

Makes you wonder who your real friends are…

————-

End of letter

————-

I find the points that my (real life) friend makes here highly disturbing, but I suspect that they also fit with what we now know about dishonesty.

First, although there are many ethically questionable practices occurring here, it’s not clear that anything illegal is going on. Second, I think that while this banking industry’s IPO process is artfully designed in such a way that, although overall it’s good for the bankers and less so for the companies, no single individual believes he/she is doing anything wrong. Third, I also suspect that since this is such a common practice, the bankers most likely truly believe that mechanisms such as getting a first-day IPO “pop” is great for Facebook and that the Greenshoe is fact put in place to stabilize the Facebook stock price, and not simply to generate more windfall profits for themselves. Forth, they probably believe in their own definition of a “successful” IPO, which in their terms is one where the stock is priced at $40 and quickly trades up to $50. In the case of Facebook, this process simply redistributes $4 billion from Facebook to the banks and the large fund managers. For Zuckerberg and his team, I have to wonder whether the emotional value of a first day share price “pop” is worth $4 billion.

I am not sure about you, but I find all of this very depressing.

Irrationally yours,

Dan

Asking the right and wrong questions

From a behavioral economics point of view, the field of financial advice is quite strange and not very useful. For the most part, professional financial services rely on clients’ answers to two questions:

- How much of your current salary will you need in retirement?

- What is your risk attitude on a seven-point scale?

From my perspective, these are remarkably useless questions — but we’ll get to that in a minute. First, let’s think about the financial advisor’s business model. An advisor will optimize your portfolio based on the answers to these two questions. For this service, the advisor typically will take one percent of assets under management – and he will get this every year!

Not to be offensive, but I think that a simple algorithm can do this, and probably with fewer errors. Moving money around from stocks to bonds or vice versa is just not something for which we should pay one percent of assets under management.

Actually, strike that. It’s not something we should do anyway, because making any decisions based on answers to those two questions don’t yield the right answers in the first place.

To this point, we’ve run a number of experiments. In one study, we asked people the same question that financial advisors ask: How much of your final salary will you need in retirement? The common answer was 75 percent. But when we asked how they came up with this figure, the most common refrain turned out to be that that’s what they thought they should answer. And when we probed further and asked where they got this advice, we found that most people heard this from the financial industry. Sort of like two months salary for an engagement ring and one-third of your income for housing, 75 percent was the rule of thumb that they had heard from financial advisors. You see the circularity and the inanity: Financial advisors are asking a question that their customers rely on them for the answer. So what’s the point of the question?!

In our study, we then took a different approach and instead asked people: How do you want to live in retirement? Where do you want to live? What activities you want to engage in? And similar questions geared to assess the quality of life that people expected in retirement. We then took these answers and itemized them, pricing out their retirement based on the things that people said they’d want to do and have in their retirement. Using these calculations, we found that these people (who told us that they will need 75% of their salary) would actually need 135 percent of their final income to live in the way that they want to in retirement. If you think about it, this should not be very surprising: If you add 8 hours (or more) of free time to someone’s day, they will probably not want to spend this extra time by going for long walks on the beach and watching TV – instead they may want to engage in activities that cost money.

You can see why I’m confused about the one-percent-of-assets-under-management business model: Why pay someone to create a portfolio that’s 60 percent too low in its estimation?

And 60% is if you get the risk calculation right. But it turns out the second question is equally problematic. To show this, we also asked people to tell us how much risk they were willing to take with their money, on a ten-point scale. For some people we gave a scale that ranges from 100% in cash on the low end of the risk scale and 85% in stocks and 15% in bonds on the high end of the risk scale. For other people we gave a scale that ranges from 100% in bonds on the low end of the risk scale and buying only derivatives on the high end of the risk scale. And what did we find? People basically looked at the scale and said to themselves “I am a slightly above the mean risk-taker, so let me mark the scale at 6 or 7.” Or they said to themselves “I am a slightly below the mean risk-taker, so let me mark the scale at 4 or 5.” In essence, people have no idea what their risk attitude is, and if they are given different types of scales they end up reporting their risk attitude to be very different.

So we have an industry that asks one question it’s giving the answer to, and a second question that assumes that people can accurately describe their risk attitude (which they can’t). This saddens me because, while I think that financial advisors are overpaid for the service they provide, in principle they could contribute much more, and they could even deserve their salary. But only if they start offering a more useful service, one that they are in the perfect position to provide. Money, it turns out, is incredibly hard to reason about in a systematic and rational way (even for highly educated individuals). Risk is even harder.

Financial advisors should be helping their clients with these tough decisions! Money is about opportunity cost. Every time we think about buying a car or going on vacation we should be asking ourselves what we won’t be able to afford in the future if we go ahead and make this purchase. And that’s where the financial advisor should come in.

It’s possible that the best financial advisors already do help in this way, but the industry as a whole does not. It’s still centered on the rather facile service of balancing portfolios, probably because that’s a lot easier to do than to help someone understand what’s worthwhile and how to use their money to maximize their current and long-term happiness.

The fact is that money is hard to think about and we do need help with making financial decisions. The financial consulting profession has an opportunity to reinvent itself to service this need. And if they do, it will be beneficial for both financial advisors and their clients.

——————–

A shorter version of this appeared at hbr.org

Late but maybe still useful

Here are a few suggestions I gave for eating less on thanksgiving:

1) “Move to chopsticks!” Or, barring that, smaller plates and utensils.

2) Place the food “far away,” so people have to work (i.e., walk to the kitchen) to get another serving.

3) Start with a soup course, and serve other foods that are filling but low in calories.

4) Limit the number of courses.

Variety stimulates appetite. As evidence, consider a study conducted on mice. A male mouse and a female mouse will soon tire of mating with each other. But put new partners into the cage, and it turns out they weren’t tired at all. They were just bored. So, too, with food. “Imagine you only had one dish,” he says. “How much could you eat?”

5) Make the food yourself. That way you know what’s in it.

6) “Wear a very tight shirt.”

Enjoy

The value of advice (by Alon Nir)

A few days ago Dan wrote about Don Moore’s research on how we accept advice from others. A lab experiment showed that subjects adhered to advice from confident, not necessarily accurate, sources. The findings of another research, led by Prof. Gregory Berns of Emory University, show another aspect of our reaction to advice.

Berns recorded his subjects’ brain activity with an fMRI machine while they made simulated financial decisions. Each round subjects had to choose between receiving a risk-free payment and trying their chances at a lottery. In some rounds they were presented with an advice from an “expert economist” as to which alternative they consider to be better.

The results are surprising. Expert advice attenuated activity in areas of the brain that correlate with valuation and probability weighting. Simply put, the advice made the brain switch off (at least to a great extent) processes required for financial decision-making. This response, supported by subjects’ actual decisions in the task, are troublesome, perhaps even frightening. The expert advice given in the experiment was suboptimal – meaning the subjects could have done better had they weighted their options themselves. But how could they? Their brains were somewhat dormant.

We’re Swayed by Confidence More than Expertise

“For the great majority of mankind are satisfied with appearances, as though they were realities, and are more often influenced by the things that ‘seem’ than by those that ‘are.'”

-16th-century Italian politician Niccolo Machiavelli

It’s something we come across regularly: presentation trumps content. Often what matters is not what we know, or what we have done, but rather how we spin it. It’s why cover letters are so important, and why the peripheral route to persuasion – one of advertising’s biggest weapons – works.

Now, Don Moore of Carnegie Mellon University demonstrated yet another way that we are heavily influenced by delivery — We tend to seek advice from experts who exhibit the most confidence – even when we know they haven’t been particularly accurate in the past.

In his experiment, Don had volunteers guess the weight of people in photographs, and paid them for their correct answers. But before each guess, the volunteers were asked to choose one of four advice-givers (also volunteers) from whom to buy advice. Each advice-giver submitted their weight guess in percentage form, with some advisers spreading out their advice over multiple weight ranges. So, one advisor might have said that there was a 70% chance that the person’s weight was 170-179 pounds, a 15% chance that it was 160-169, and a 15% chance that it was 180-189. A more confident advisor, however, would have put all his eggs in one basket and said there was a 100% chance that the weight was within the 170-179 range.

Now here’s the really important part: in each round, before they chose their adviser, volunteers got to see each adviser’s percentage spread, but not the associated weight ranges. (See this really handy chart for more on the set-up.)

What did Moore find? Volunteers were more likely to buy advice from confident advisers (such as the 100% adviser from above) than those who spread out their percentages. What’s more, this tendency led advisors to make their advice more and more precise in subsequent rounds – but not more accurate.

These findings are troublesome. Because though confidence and accuracy sometimes go hand-in-hand, they don’t necessarily do so. And when we want confident advisors, some will exaggerate to give us what we want. Maybe this is why so many pundits on TV for example exaggerate their certainty?

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like