Life (and the Pursuit of Happiness)– But for How Long?

Confronting our mortality is not an easy task for most people. However, there are many reasons people should consider just how long they might live.

In the case of retirement planning, life expectancy is important in relation to the benefits like Medicare and Social Security that people earn during their working years. According to the Pew Research Center, use of these government benefits programs is “virtually universal (97%) among those ages 65 and older—the age at which most adults qualify for Social Security and Medicare benefits.”

Differences in life expectancy between the rich and the poor can mean that more affluent Americans receive hundreds of thousands of dollars more in benefits that those who are less well off. In addition to the economic considerations, there is a psychological and perhaps even moral factor that comes into play when thinking about how long we might expect to live in relation to our financial status.

Topic 3 in Fair Game? asked users to think about exactly this question and to estimate how income is related to life expectancy and what that relationship should be in a fair world.

“It will surprise nobody to learn that life expectancy increases with income.”— Michael Specter, 4/16/16, The New Yorker

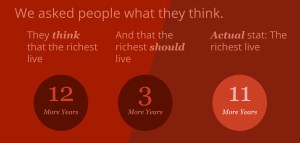

On the whole, our users estimated that the richest 10% of society would have a life expectancy 12 years longer than the poorest 10%. In reality, the difference is 11 years (12 additional years for men and 10.1 additional years for women).

How many more years of life do they think the wealthy should expect in a fair world? 3 more years (a 75% reduction from their estimate of what is true).

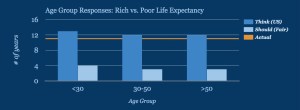

Estimates for the current difference in life expectancy were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair. Preferences for a fair difference were also similar. There may be hints of a difference between younger and older adults, with a possible explanation simply being ‘mortality salience’, or how much longer users themselves’ expect to live.

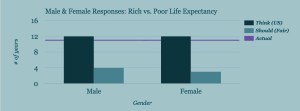

What about gender? Both males and females estimate 12 more years of life for the top 10%. But they differ slightly in what they think a fair amount of additional years would be — 4 vs. 3, respectively.

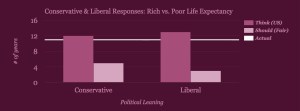

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal only differed by 1 year in terms of what they believed the life expectancy gain from wealth to be, and 2 years in what they thought it should be in a fair world. Conservatives estimate the gain to be 12 years, while liberals put it at 13 years. In terms of what they think would happen in a fair society, conservatives consider 5 years and liberals consider 3 years to be a fair number of years gained with wealth. Despite these small differences, the presumed improvement (from what is thought to what it should be) ends up being 7 years for conservatives vs. 10 years for liberals.

Together, the data reported here suggest that estimations of the present gap in life expectancy are fairly accurate. And that small differences in life expectancy (3-5 years) are considered fair (or perhaps tolerable) by most people. Has the wealth-based life expectancy gap always been this large? According to a Brookings report, it has actually grown from 4.5 years (for the cohort of seniors born in 1920) to 11 years (for the cohort born in 1940). It is likely that multiple factors, including differential access to quality medical care, and higher rates of smoking and obesity, contribute to the growth of this gap. On top of all of this, wealthier people typically retire later and can delay receiving social security payments, thereby increasing income inequality in the older population.

Unfortunately, public benefits that were originally intended to be progressive seem to be becoming (unintentionally) regressive over time. Perhaps there are some solutions that might help to keep more Americans living long, happy, and healthy lives?

What do you think? Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

“Equal Pay for Equal Work”

It’s a simple statement but it represents so much more than just four words. For many people, it is a rallying call for closing the gap between men’s and women’s wages, ultimately achieving the goal of pay equity, and protecting a notion of basic fairness.

Others question the very idea of what equal work means, with some people arguing that women make different career choices compared to men and that any gap is merely a reflection of those choices. But in the United States, there are many historical examples of inequality affecting women including: denial of property rights, the right to vote, the ability to obtain higher education, and barriers to particular occupations and specialized careers.

Given the complex history of women’s equality in the U.S., we wanted to find out what people think about the current state of working women and their pay relative to men. We focused on the gender wage gap for topic 2 of Fair Game?, our new app that asks users what they think about the world as it is today and what they would want in a fair world.

Surprisingly, people tend to overestimate the gender wage gap and believe women earn 73% of men’s income. In reality, women are estimated to earn 79% of men’s income.

How much do people think women should be paid in a fair world? 93% of men’s income.

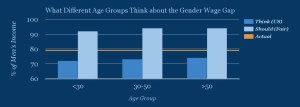

Overall, responses did not dramatically differ by the age of the user.

How does your own gender relate to what you think about this? Male and female users both overestimated the magnitude of the gender wage gap, with men thinking women currently earn 74% of men’s salaries, and women estimating that they earn 70% of men’s salaries.

There was closer agreement for the question of what a fair wage gap should be, with males preferring 93% and females preferring 94% of men’s salaries. On the whole, both genders perceive a gap to exist in the United States and would substantially – but not completely – close that gap in a fair society.

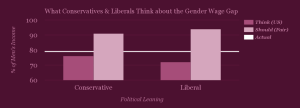

And can we observe differences in views according to political beliefs? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal only differed by 4% in terms of what they believed the gender wage gap to be, and 3% in what they thought it should be in a fair world. Conservatives estimate women’s salaries to be 76% of men’s, while liberals put that percentage at 72%. In terms of what they think would happen in a fair society, conservatives consider 91% and liberals consider 94% to be a fair ratio of women’s to men’s income. Despite these relatively small differences, on average, the increase in women’s salary thought to yield fairness would be 15% for conservatives vs. 22% for liberals.

The gender wage gap is a topic that deserves careful consideration. Although a single number represents an average for all women, the number varies substantially once we consider factors including race, age, education, profession, career trajectory, childbirth status, and U.S. state of residence, to name a few.

There is also likely to be some gender role stereotyping at play in the results we received, with many of our respondents probably assuming that the burden of childcare would or should fall disproportionately on women.

This is a complex topic, but we can learn from some efforts to equalize opportunities in the workplace for women. A program in the Canadian province of Quebec provided an interesting natural experiment, demonstrating that subsidized daycare could support an upsurge in employment of women that in turn boosted economic output to a level that more than paid for the childcare subsidy costs1.

A final consideration is how long it will take to close the gender wage gap, given the progress that has already been made. One measure of improvement (the upward trend since the 1960’s), predicts the gap to close by 2059. But if a recent slowdown in the trend persists, the gap would not close until 2152. What other efforts do you think might be worthwhile to pursue to help close this gap, sooner or later?

And please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

- Fortin, Pierre et al. (2012). Impact of Quebec’s Universal Low-Fee Childcare Program on Female Labour Force Participation, Domestic Income and Government Budgets. Sherbrooke: Research Chair in Taxation and Public Finance, University of Sherbrooke.

Ask Ariely: On Celebratory Savings, Tools for Temptation, and Anticipating Activities

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My wife and I recently had our first child. We know that friends and family, especially grandparents, like to buy gifts for children for birthdays and holidays. But we have set up a college savings account for our child and would much prefer to have our loved ones put money into this account rather than buy things that our child doesn’t really need. How can we encourage this more rational behavior?

—Kyle

Though giving money is often more economically efficient than giving stuff, the feeling of social connection that we get from gift-giving is higher when we give something tangible. If I were you, I would try to provide the gift-givers with a chance to do a bit of both. You can ask them to buy something small for your child and also to put some money in the college fund.

If you want an even higher proportion of the money to go to the college fund, buy a nice book with blank pages and on its cover write your child’s name and the word “future” (“Dan’s Future,” for example). You can then ask each gift-giver to put money in the college fund and, at the same time, to share some advice for life by writing on one page of the book. This way, there will be a physical reminder of their gift (the book and the advice), but more of the money will go to the college fund.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am trying to stop using Facebook because it only wastes my time and makes me feel bad about myself. But despite repeated attempts to stay away from my Facebook page, I keep coming back to it. I think part of the reason is that I’m so impulsive. Do you have any advice on how I might finally break my Facebook habit?

—Maryam

My recommendation is to create some sort of “Ulysses contract.” As you will recall from Homer’s ancient tale, Ulysses knew that if he allowed himself to hear the tempting calls of the Sirens, he would follow them and in the process kill himself and his crew. So he asked his sailors to tie him to the mast of his ship and put wax in their own ears. Ulysses thus protected himself from temptation by making it impossible to take action when temptation appeared. He didn’t have to summon his willpower to resist.

Maybe you can make your own Ulysses contract by asking a friend to change your Facebook password and not to tell you what it is for a month. This will give you a chance to see what life without Facebook feels like and to decide if that is indeed what you want. If it is, you can then go ahead and delete your account—and you will be free of Facebook.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I hate waiting for anything. I get very impatient when I have to wait for food in a restaurant, for my new iPhone, for the next time I will meet a good friend, etc. Is there anything I can do to make it less painful to wait?

—Maya

Sometimes anticipation can be a pleasurable part of the experience. Imagine, for example, that you could get a kiss from your favorite movie star. Would you rather get the kiss in the next 30 seconds or in a week? When faced with this question, most people prefer to wait because, in the end, a kiss is just a kiss, but waiting for a unique kiss can be wonderful. My advice is that you try to get into such a mindset for other experiences as well, and instead of thinking about waiting as a delay, think about it as an opportunity for anticipation.

P.S. I got this question from you a few months ago, and I hope that you enjoyed anticipating my response.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Sanitation Solutions, Neighbor Needs, and Popular Politics

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I was recently at a barbecue restaurant where the toilets were private but the sinks were out in the open, in a common space. Would moving sinks to public areas get more people to wash their hands? Would you recommend this setup for all public bathrooms?

—Brian

Absolutely, and here’s why.

Sometimes, to show the extent of our irrationality, I will ask a large group, “In the past month, how many of you have eaten more than you think you should?” Almost everyone raises their hands. “In the past month, how many of you have exercised less than you think you should?” Again, everyone raises their hands. “In the past month, how many of you have texted while driving?” Almost everyone raises their hands.

Then I ask, “In the past month, how many of you have left the bathroom without washing your hands?” The result: almost perfect silence, no hands raised and, after a few embarrassed seconds, a bit of nervous laughter.

Obviously, they are lying—but why won’t people who have just confessed to something as reckless and stupid as texting while driving admit that they sometimes don’t wash their hands? I suspect that it is because we care pretty intensely about not being disgusting to others. As such, putting the sinks somewhere public and visible should encourage more hygienic behavior—ideally, with our friends and relatives watching over us to be extra-sure we do the right thing.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I hear the phrase “keeping up with the Joneses” a lot. But is there good evidence that we really care about what our neighbors have or that we change our behavior accordingly?

—Michelle

Yes and yes: There is good evidence of our tendency to try to keep up with those around us. In one recent paper, the economists Sumit Agarwal, Vyacheslav Mikhed and Barry Scholnick looked at the neighbors of lottery winners and discovered that they tended to buy more cars and other clearly visible assets. These “signaling purchases,” the study suggests, were influenced by the presence of suddenly rich neighbors, but the researchers found no increase in the savings or other invisible assets of the less lucky neighbors. Depressingly, those living near lottery winners were more likely to suffer financial distress and even bankruptcy.

These results show that our decisions aren’t just influenced by what we desire but also by our social drive to keep up with those around us. So it makes sense for us to spend a bit more time thinking about who we want to befriend and live next to. If we are going to try to keep up with the Joneses, we should pick the right Joneses.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

The polling averages now show Hillary Clinton with a significant lead over Donald Trump. Will these favorable polls help or hurt her?

—Josh

The forces here point in both directions. On the one hand, you can imagine that people who support the front-runner could say something like, “My candidate is going to win anyway, so I can stay home”—which obviously hurts their candidate. On the other hand, a candidate’s popularity could well reinforce itself and create a herding effect, which would help whoever is up in the polls.

Which of these two forces is more powerful? The evidence points to the herding effect: For better or worse, we just seem to like to follow.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Family Photos, Moving Money, and Authoritative Acronyms

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I consider myself a steadfast atheist, but I have an irrational dilemma: Every time I want to throw away things that I no longer need, I find myself unable to chuck out anything that belonged to my parents. I can’t even part with their old pictures, which I have digitized and stored permanently on my hard drive. Am I being ridiculously superstitious?

—Eve

Religious belief and superstition aren’t really the same thing. Paul Rozin of the University of Pennsylvania has done excellent research showing that we are all superstitious, to some extent. In one of his experiments, participants were asked to throw darts at a target and were rewarded the closer they got to its center. Sometimes the center was the image of a beloved figure like President John Kennedy; sometimes it was someone widely despised, like Saddam Hussein.

People hit the bull’s-eye more for Saddam and missed more for JFK. They knew, of course, that pictures aren’t the same as people, but they still attached some of the person’s symbolic meaning to the images, which made it harder to harm them.

This type of emotional link means that when you think about throwing out your parents’ belongings, you feel as if you are discarding a part of them. My advice? Send the items that you don’t want but can’t destroy to your siblings or other relatives and let them deal with them.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m renting an apartment with two friends. One of them is moving in on August 24. I plan to move in on August 29, and the third friend is planning to join us in early September. Our landlord will charge extra rent for those days in August. Who should pay?

—Randy

The right way to split the cost depends on the timing and sequencing. If the lease was always set to start on August 24, then you should all split the cost because you all undertook the responsibility of starting the contract together. But if the contract could have started on any day, and your first friend pushed you into starting it on August 24, that friend should be on the hook for funding the extension. Fairness mandates considering the process here, not just the final outcome.

That said, remember that you’re all going to be roommates, perhaps for a long time, and starting your joint life together by protracted haggling may open the door to years of annoying accounting discussions (“You had an extra swig of the milk, so you owe me 75 cents”) rather than years of deep friendship. With this in mind, I suggest dividing the rent equally—but also asking the people moving in early to do more to set up the apartment, call the cable company, get basic supplies and figure out where the furniture goes. That way, they will contribute more to the overall endeavor but in a way that is compatible with long-term friendship.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

We have lots of meetings at my office, and when I speak up, I often worry that as a rather junior female employee, I don’t sound as if I have enough authority. Any advice about how to seem more commanding?

—Katherine

One of the best ways to increase your perceived authority is to start using acronyms. My favorites are WAG (Wild-Ass Guess) and SWAG (Scientific Wild-Ass Guess). My SWAG is that deploying a few well-placed acronyms the next time you make a point will give your gravitas quotient (or GQ) a boost.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Shorter Shifts, Clever Communication, and an Irritating Invasion

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A big local employer just announced that it is about to change its standard workday from eight hours to five. I suppose many people barely do two or three hours of good work a day anyway, but is shrinking the workday so drastically a good idea? in italics

—Bernard

To think this through, let’s break down our workday into three modes: productive, thoughtful, useful work; mindless, detail-oriented work that doesn’t demand much concentration but must get done; and, of course, wasting time.

When the workday is slashed from eight hours to five, which of these modes is likely to give way? If the three lost hours would otherwise have been spent procrastinating, the change is all to the good: We can waste time better on our own. And if it comes at the expense of drudge work, many people will just become more efficient at their more mindless tasks, with a minimal drop in productivity.

But I fear that those three hours will come at the expense of the most productive category of work. That’s because everyone likes the sense of satisfaction from making progress. We feel virtuous after emptying our email inbox or checking off items on our to-do lists. If the workday shrinks, we’d rather sacrifice real progress than surrender that feeling of gratification.

If we now split an eight-hour workday between one hour of thumb-twiddling, four hours of drudgery and three hours of serious work, I’d predict that the shorter workday will mean a half-hour less of wasted time, an hour less of mindless work and an hour and a half less of meaningful work.

This is just an educated guess, of course. If I ran your workplace, I would start by cutting the workday by 30 minutes, see what this does to productivity and adjust from there.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When you have to deliver two pieces of news, one bad and one good, which should you start with? I’ve always been told to deliver the bad news first, but I worry that its impact could be so distracting that the recipient won’t pay attention to the good news that follows.

—Galia

Why pick from just this constrained set of options? Is there really nothing else in the universe to share? I’d come up with another piece of good news to start with, such as the fact that we have eradicated smallpox and polio could be next—admittedly less relevant but undeniably cheerful. You can then sandwich your bad tidings between good ones.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

While writing a document on my laptop with a colleague, he kept pointing to my screen and sometimes touched it with his finger. I found this incredibly annoying—and a strange invasion of privacy. I wouldn’t have minded if my co-worker had touched my arm, but I bristled when he touched my screen. What gives?

—Kim

After reading this, I asked a few people nearby to touch my laptop and then my elbow, and I felt the same irritation. I suspect that’s because once people touch our computer screens, we can’t avoid seeing the gross residue that their fingers leave, but we don’t think about the oil and dead skin cells left behind when somebody nudges us on the arm. Consider this more evidence that ignorance can be bliss.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Losing Leftovers and Stressful Situations

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

At a holiday potluck that I attend each year, the hostess asks each guest to bring a specific dish. We always wind up with too much food, but the hostess never asks us whether we would like to take any leftovers home. I think that the food I made and brought should be considered mine. So who do the leftovers belong to, the hostess or the cook/guest?

—Sigrid

This is a tricky one. Usually, if we are invited to someone’s house for dinner and bring, say, a bottle of fine whiskey, we wouldn’t expect to take the rest of the bottle back home with us. But a potluck isn’t your standard dinner party, and it isn’t clear what rules apply. You gave the food, which was accepted by the host—but she did so on behalf of the group, which didn’t finish it.

Ethics aside, I see three practical ways to resolve the problem. First, you could make something that is physically hard to separate from the dish in which you brought it. If, for instance, you brought crème brûlée in a large ceramic dish, you’d make it clear that the dish was yours, and because it would be difficult to separate it from the leftover dessert, you would get to take them both home.

Alternatively, you could bring your contribution in two containers, hand one to the host and tell her that you have another container in case your fellow diners polish off the first one. You wouldn’t have to hand over the second part of your offering unless it turned out to be needed, and you’d have a decent shot at getting to take it home.

Or you could whip up a crowd-pleasing recipe that you happen not to like. The point of a potluck is to have fun with friends, not to fret about who gets what at the end. So just make something you don’t care for. You won’t care who inherits the leftovers, and you’ll enjoy the party more.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I went to the bathroom at a new restaurant in town only to find a large, modern-looking stainless-steel urinal, without partitions, which put everyone in plain view of his fellow patrons. I tried to finish my business quickly and get out of there. Am I the only one made uncomfortable by such arrangements?

—Greg

Actually, many men are made uneasy by such bathroom settings, but I suspect that you didn’t finish your business any faster.

In 2005, my students and I carried out an experiment at MIT. Sometimes, we had one of our students stand at the middle urinal in the men’s room, pretending to go and waiting for unsuspecting visitors. Other times, we didn’t have anyone from our team at the urinals. In all cases, we had a student hiding in a nearby stall with a recorder.

That let us pick up two aspects of urination: its onset (from the time a subject situated himself at the urinal to the moment when we first heard liquid sounds) and its duration (until those sounds stopped).

We found that men took longer to get going when they had company nearby, presumably because of social stress. But once they started, they finished faster—again, presumably because of stress and the desire to get out of there. The total amount of time was slightly slower than when men were left alone.

Of course, our participants were undergraduates with splendid bladder control, so we might need to repeat this study with a more mature population.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Genuine Greetings, Moral Reminders, and Interest Aversion

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

We often greet each other by saying, “How are you?” But most of us probably don’t really want a long answer. Why do we do this?

—Warren

Dear Dan,

To reduce cheating at the high school where I teach, we ask students to sign an ethics code before each exam and on every paper they submit. I’d estimate that they sign the code at least once a week. Your own research, I gather, shows that getting students to sign a similar ethics code just once helps to reduce cheating. What about signing it more often? Does overuse make it ineffective?

—Elliott

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I find it easy to avoid reckless spending. I don’t own a credit card because I hate the concept of interest, and I’m paying my daughters’ college tuition (they know that they have to pay me back) because if they took out loans, I’d have to co-sign and might be on the hook for the tuition and interest. Am I just more rational than other people?

—Wei

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Roommate Relationships, Painful Priorities, and Admitting Aging

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I live with several roommates, and our landlord recently refunded some of our rent to make up for construction-related hassles in the building. What should we do with the money? We could divide it among ourselves, use it for house supplies or get a bigger TV to watch movies together. How should we think about this?

—Kristen

I vote for doing something fun with the windfall—ideally something that would let all the roommates have a new experience together. Your relationships with each other are, I suspect, the biggest contributing factor to your happiness (or misery) at home: When they are good, life smiles on you, and when they are bad, you probably tend to stay out as much as possible.

Doing some activity together—say, sailing, skydiving or learning a new skill—would bring all of you closer and encourage you to be nicer to each other. You would ordinarily have a hard time asking everyone to chip in for an expensive group activity; after all, you are roommates, not standard friends.

But a refund from your landlord should feel more like free money—cash that no one planned on having and that everyone can probably manage without. That should make it easier to persuade your roommates to partake in some group-bonding activity.

Looking for the ideal skill to learn together? I would suggest a cooking class. You’ll not only have fun learning something new, but you’ll also enjoy better food—and perhaps the joy of cooking for each other for a long time.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

It has increasingly struck me that humans feel pain much more intensely than pleasure. Is this true, and is there a reason why pain affects us more?

—Brian

Yes, we do experience pain much more intensely, which makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. In general, nature wants to teach us to seek things that are good for us or the species (food, warmth, sex), so these give us pleasure. Nature also wants us to stay away from dangerous things (predators, toxins, fire), so these give us pain.

One might imagine that the things nature wants us to seek would give us pleasure, while the things that we should avoid would leave us feeling neutral. But the benefits and harms of life aren’t symmetrical. A good outcome (a delicious piece of fruit, for example) can give us some modest benefit, but a bad outcome (say, poison) can kill us—which is a very significant downside.

If the evolutionary priority for us is to seek good outcomes but especially to avoid bad ones, then our tendency to focus on pain (and potential pain) is a pretty effective way to shape our behavior. Even during painful times, I’ve found that a somewhat comforting thought.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A friend of mine from work is turning 45. What should I get him?

—Janet

If he doesn’t have reading glasses, get him a pair. People generally delay getting reading glasses, because it is hard to recognize the slow deterioration of our vision and because it means admitting that we are aging. If you give your friend a pair, you will spare him the procrastination, and he will immediately realize that he has been living in a blurry world. He might not immediately feel deep appreciation, but it would still be a very helpful present.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Switching Stylists, Blood Loss, and a Broadcasting Behavior

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am 65 and have been going to the same hair salon for ten years. I have gotten to know well the experienced stylist who cuts my hair. Recently, she had to cancel two appointments, so I got my hair cut by her former protégé, who works at the same shop. I discovered that I like the way the protégé cuts my hair better. I don’t see any way of switching to the younger stylist because of the social problems it will cause me and the stylists themselves. Both of them work the same hours on the same days.

I guess at my age, I just have to live with it. But I wonder, using my situation as an example, how can someone make such a change when faced with a similar dilemma?

—Alvin

I don’t think you have to resign yourself to worse haircuts. You could instead use a positive message to tell your long-time stylist that you’d like to switch. You could tell her that you are trying to make changes in as many areas of your life as possible—and that if she doesn’t mind, you would like to try the other stylist. At age 65, why not take the statement seriously and try to change some other things in your life and explore other new directions?

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When my grandfather died in a house fire decades ago, he had been a blood donor for 70 years. I made it my mission to continue donating “for him.” I lived in Belgium at the time and donated with the Red Cross every 3 months.

When I moved to California, I decided to continue donating blood, but there was a problem: I had to lie on the questionnaire about whether I had spent time in Europe in the 1980s. The fear was contamination from mad cow disease. There was never a case of it in Belgium, ever, so I didn’t feel that I had to disclose that part of my past. After my most recent donation, the Red Cross became suspicious of my personal history, and now they have caught me. I am convinced that my blood will be destroyed and I will be barred from donating ever again.

I am beyond sad and feel that I broke my promise to my dead grandfather. What advice do you have to offer me?

—Christie

From time to time, we all experience rules that we think are strange, crazy, over strict, applied inappropriately and so on. But we also have to remember that very large organizations like the Red Cross have to create some rules in order to operate efficiently and safely. It would have been better not to lie to the Red Cross, even at the cost of not being able to donate blood.

As for your commitment to your grandfather, I think that you should understand it only as doing your best to donate. You have no control over whether the Red Cross accepts your blood, and you should not blame yourself. Given that you still want to honor your grandfather, how about donating money to the Red Cross or a local burn unit?

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What’s the best way to deal with a difficult teenage boy? He stays out as much he can; he’s rude and dismissive; and he refuses to do chores. Whenever he’s away from home, he’s charming. Any suggestions?

—Claudia

The good news is that he is charming away from home, which means that he is capable of being nice. Sadly, he does not seem to be interested in acting this way with you.

What if you set up a webcam in a very visible part of the house and made it clear that his behavior would be streaming to Facebook for his friends to see? That way, he might bring his outside behavior into the house. After a few weeks of this, he might develop new habits toward his family, and you could turn off the camera (but maybe keep it there unplugged, just as a reminder).

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like