Duke Losing and the Joy of Underdogs

I am a scientist and occasional season ticket holder at Duke. So on Friday, I was understandably sad with the Duke loss. But as I watched the rest of America celebrate on Twitter, I felt no anger toward everyone else’s joy. Because everyone else got to experience the same joy that I long to experience each time I watch a top seed (that isn’t Duke) playing a low seed. Like so many, I want to see the underdog win.

Because no matter whether you’re a punk or prep, a janitor or CEO, or work at Mercer or even Duke, at times you feel like an underdog. Maybe you’ve been given the lowest step on the economic ladder, maybe you’re a struggling artist, or maybe you’re a scientist battling to modernize research. At the end of the day, so many of us feel like underdogs and we want nothing more than to see another underdog succeed.

Luckily for us, we can count on the annual March Madness to provide a few underdog success stories. And then millions of us can flock to a momentary allegiance with a college we have to use Google Maps to locate. In the past it has been George Mason, Virginia Commonwealth University, and Butler, and this year we’ve momentarily been given quite a few more.

In America, especially compared to other countries, the underdog narrative is an honorable and relatable narrative. From the American patriots in 1776 to the George Mason Patriots in 2006, the story has always been part of this country’s culture.

From March Madness to Luke Skywalker, we Americans crave more and more stories about underdogs. We demand it in every fictional and nonfictional story. Even the more privileged characters in popular storylines, such as the elite James Bond or billionaire Tony Stark must at sometime become outcast underdogs. If they didn’t we wouldn’t relate to them. The narrative is so much a part of our culture that politicians are forced to conform to the underdog narrative, even if they really don’t fit it.

In fact, the narrative is so strong that Neeru Paharia of Georgetown University and colleagues named a psychological effect after it, simply naming it “The Underdog Effect.” They found that groups (e.g. companies or maybe even basketball teams) can gain goodwill from others when they present themselves as underdogs. This effect was stronger for people who personally related with the narrative and stronger in cultures where the narrative was more prevalent (e.g. America).

More than ever, today we need these stories. Many political pundits on both sides of the spectrum have argued that the hope of the American underdog dream is fading. For this reason we are desperate to keep this important hope alive. Believing that an underdog will win in Texas this year might be a good way to keep the flame of that hope burning.

If only for my sake, that hope didn’t require a Duke loss. Oh well. Time for me to start rooting for a school I know nothing about. I need to leave you all now. I’ve got some Google mapping to do.

The Starbucks Effect

The Effect

When we order a fancy drink at Starbucks (or some fancier coffee house) with funny language, we believe we are sophisticated connoisseurs. But when others do the exact same thing, we just see them as annoying poseurs.

The Problem

But we don’t just believe we are hot stuff when we order at Starbucks, we also believe that other people will think we are hot stuff. This “self-serving” bias can be dangerous.

Across domains, people believe their dates will be won over by their charm, entrepreneurs believe investors will be won over by their ideas, and “connoisseurs” believe everyone will be won over by their “sophistication.”

It’s one thing to believe you are great, but it’s another thing to project your grand self-perceptions on the others’ perceptions of you. This is when biases can start to multiply and problems can go so awry. While this may not lead to tragic results in a Starbucks line, it can in love, politics, business, and academia.

~By M.R. Trower and Troy Campbell~

~Illustration by M.R. Trower~

A Pot’o’Gold for St. Patrick’s Day

Want your very own bag of BiteCoins? Click Here.

Ask Ariely: On God’s Image and Marriage Money

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why are there so many religions, all of which suggest that God is on their side and holds the same values that they do?

—Moshe

One answer comes from a 2009 study by Nick Epley and some of his colleagues from the University of Chicago, which asked religious Americans to state their positions on abortion, the death punishment and the war in Iraq. (This study is described in Dr. Epley’s recent book, “Mindwise: How We Understand What Others Think, Believe, Feel, and Want.”) Participants were then asked to predict the opinions of a few well-known individuals (such as Bill Gates), President Bush, the “average American,” and—and uniquely to this study—God on these issues.

Interestingly, the respondents were rather objective about predicting the opinions held by their fellow humans, but they tended to believe that God had similar opinions to their own. Conservatives believed God was very conservative; liberal believers were certain that God was more lenient.

To find out why we can view God so flexibly, a follow-up experiment asked another group of participants to take the position on the death penalty diametrically opposed to their own and argue this viewpoint in front of a camera. A large body of research on cognitive dissonance has shown that people who are forced to argue for an opinion opposite to their actual one feel so uncomfortable with the conflict that they’re likely to change their original opinion. After giving their on-camera speech, participants were again asked to express the views on these hot-button issues of the study’s famous individuals, President Bush, the “average American” and God.

The results? After expressing the opinion opposite their original one, individuals became more moderate. Those who disliked the death penalty became less opposed, and those who were for it became less so. But there was no such shift in participants’ predictions of the opinions of the well-known individuals, President Bush or the “average American.” And what about their predictions about God’s views? Participants tended to attribute the same position as their own new, more moderate viewpoint to God.

God, apparently, is something of a clean slate on which we can more easily project whatever we wish. We subscribe to the religious group that supports our beliefs, and then interpret Scripture in a way that supports our opinions. So if there is a God, I believe—no, I’m sure—that that (s)he thinks the way I do.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My partner and I will soon be married, and in honor of the event, his parents have promised us some money. Now my parents have offered us double that amount. How can I tell my partner without making him feel uncomfortable?

—Nikki

Congratulations—I hope you’ll have a lovely wedding and a good life together.

As for your question, the problem is not just that your future husband and his parents will feel uncomfortable; it is also that your dynamics as a newlywed couple will proceed from an uneven starting point. I am not suggesting that every time that the two of you fight, you will remind your husband that it was your family’s money that let you buy a new house. But even small inequalities at the start of a marriage can have long-term effects.

If I were in your shoes, I would ask your parents to give you the same amount now that your fiancé’s parents are giving—then give you the second amount in a year, once the marriage is more established. (If you’re not sure you will stay together, maybe ask them to wait five years.)

Incidentally, since weddings are irrational in so many ways, I recently obtained a license to perform weddings through some online site—and now I’m waiting for the first couple to ask me to conduct their nuptials (hint hint).

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

A Documentary about (Dis)Honesty

It is my greatest pleasure to announce a documentary that I have been working on with Yael Melamede of Salty Features.

Today, we launch a Kickstarter campaign that will help us finish the film and build its presence in the world.

[protected-iframe id=”0c35872a2195114e20aa1c3cbc1f5c0b-1285065-1348005″ info=”https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1501481976/dishonesty-a-documentary-feature-film/widget/video.html” width=”480″ height=”360″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no”]

Please visit our Kickstarter Page to learn more about (Dis)Honesty and to become part of this special project.

Then, share the project with all your family members, closest friends, acquaintances, the cashier at your local grocery store, that guy you bumped into on the way to work, the lady whose wallet you found on the street and returned…everyone!

Thank you for your support, and I look forward to working with you along the way.

(Dis)honestly Yours,

Dan Ariely

P.S. Like The Dishonesty Project on Facebook!

And follow on Twitter: https://twitter.com/dishonestyproj

Studies across cultures: A useful guide.

Cross-cultural research is becoming increasingly popular, but many researchers are failing to understand the unique challenges it poses. Cross cultural psychology explores how culture influences behavior and attitudes, and cultural psychologists aim to study subjects from two or more cultures using equivalent methods of measurements (Triandis & Brislin, 1984).

This research can often be difficult to conduct, and as someone in the midst of working through these problems in our lab, I’ve noticed some of these difficulties. I’m sharing what I’ve learned here as a quick guide to both help other researchers design better studies and help readers know enough background to better evaluate this research.

Five Challenges of Cross Cultural Research

1. Design:

The research question and design should be very clear before embarking on cross-cultural research. And when I say clear, I mean crystal clear. What are the specific hypotheses? What analysis will you run? Do you have variables that will allow you to run those tests? Do you have proper controls?

Always start with a pilot study with at least one of the target cultures (or a population in your home country), because it’s surprising how many things sometimes just don’t work. For instance, when conducting survey research, it’s important to test your constructs, such as sub-scales. If you’re going to spend thousands of dollars and months working on a project, make sure your scales work with your population, and don’t just assume it’ll work based on past research.

2. Translations:

How can you express the exact same idea in several languages? Or in the same language but to different cultural populations, such as British vs. American, or urban vs. rural? Again, pilot testing is key. Don’t just show it to a few research assistants who speak the language, get it out to the people that you’ll be studying.

How should you actually translate? We recommend the forward-backward method, where the translated document is translated back to the original language for comparison.

3. Consistency:

As a cross-cultural researcher, you must standardize processes, settings, and other factors of your research so that the only difference between your samples is their culture. Prepare documents like protocols and scripts for experimenters, and go over them again and again. Different cultures have different customs and social behaviors, and those social behaviors, even if they’re as small as how to administer a survey in a coffee shop, cannot vary across studies without jeopardizing the data. This is problematic when you have just one culture, one survey, and one research assistant. When you have ten cultures, one survey in different languages, and many research assistants across the globe, things can get very messy, fast. Remember though, if things are messy, then it’s important to be honest about it in the write up. In the modern age of ‘imperfect’ data, reviewers are looking for and respectful of honesty.

4. Cultural Customs:

Try to have a local person or team who is willing to be involved in the implementation of the project; they will contribute greatly with local advice and organization.

There will be many local factors that you won’t be aware of if you’re not familiar with the culture. For example, you may not know where to collect data, how to deal with local businesses while asking permission, or even how to approach subjects in a nice and professional way. Things like these may vary across countries, and locals are the only ones who can fill you in. It’s also important to understand all these differences before collecting data. For instance, a methodology might work well in one cultural but, because of social norms, not in another. Again, pilot test and know as much as you can ahead of time.

5. Paying Participants:

Does your study involve paying participants? If so, make sure to adjust that payment considering the cost of living of each country. Remember $1 in the USA is not the same as $1 in other countries, so you must make payments equivalent! We recommend indexes like the Purchasing Power Parity Index (World Bank) or the Big Mac Index (The Economist). Also consider whether your samples are used to being paid to do experiments and if your payment varies from this normal payment model.

In the end, the most important thing to remember with cross-cultural psychology is to plan ahead. When evaluating cross-cultural research in journals or news articles, the critical reader should consider what factors the researchers might have overlooked.

One final consideration is to remember that all research is only part of the puzzle. There is no definitive cross-cultural psychological paper, and there never will be. So it’s important to keep each finding in perspective.

~Ximena Garcia-Rada~

Further readings about cross-cultural psychology:

– Keith, K. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Contemporary Themes and Perspectives.

– Shiraev, E. B. & Levy, D. A. (2010). Cross-cultural psychology: critical thinking and contemporary applications (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson/Allyn Bacon.

– Triandis, H. C., & Brislin, R. W. (1984). Cross-cultural psychology. American Psychologist, 39(9), 1006-1016. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.39.9.1006

– Hofstede, G., Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations

Sign up for “Irrational Behavior”

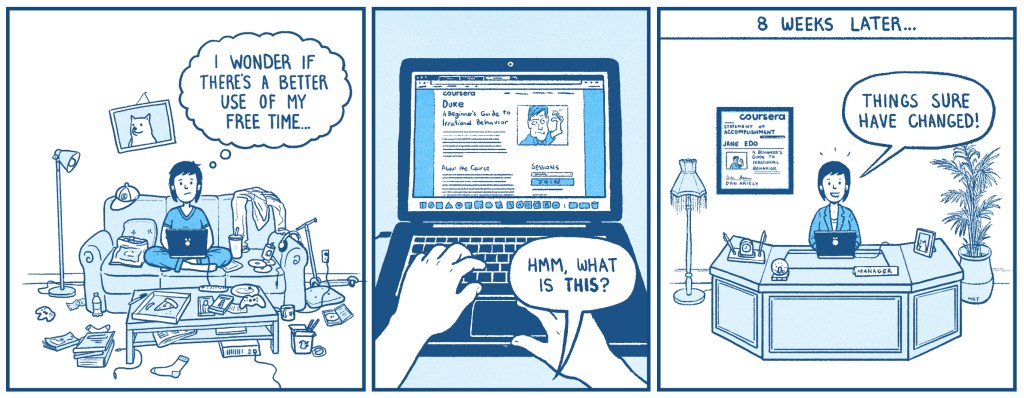

Behavioral economics is the study of humans and their (occasionally irrational) interactions with the world. Starting on March 11th, I will teach “A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior,” a glance at the peculiar mechanics of the mind. Join me for the most riveting 8 weeks of your life, and you never know — you may just end up the next CEO of the world.

Sign up here!

Ask Ariely: On Weather Delays, Time Delays, and Garlic Cologne

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I was recently stuck overnight in a strange city due to a canceled flight. Because the airline blamed the cancellation on “weather,” no one helped me find a place to stay or pay for it. Meanwhile, I saw other flights leaving the same airport. Is “weather” just a term airlines use when they try to consolidate flights, not compensate their customers and avoid blame?

—Kelly

I am sure that sometimes the weather really is at fault, but I have no idea whether the airlines use the weather excuse promiscuously when it’s to their financial advantage. It would be difficult to make such a judgment call (should we call the reason for the delay the weather or technical issues?) while completely ignoring the economic incentives involved. And blaming all kinds of things on the weather is a very useful strategy for the airlines because trapped fliers don’t directly blame the airlines for it.

But let’s be honest here: Many of us also sometimes blame our own tardiness on traffic or the weather. And I suspect many of us would blame the weather even more frequently for all sorts of lapses if we just had the opportunity.

To my mind, the weather excuse (as the airlines use it) has one major problem. The airlines’ logic is that bad weather is an act of God, which releases the airline from responsibility. But isn’t the airlines’ behavior probably the reason God is angry to begin with?

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

How can I enjoy life more? Every year, time seems to go by faster; months rush by, and years just seem to disappear. Is there a reason for this, or is the memory of time passing more slowly when we were children just an illusion?

—Gal

Time does go by (or, more accurately, it feels as if time is going by) more quickly the older we get. In the first few years of our lives, anything we sense or do is brand-new, and a lot of our experiences are unique, so they remain firmly in our memories. But as the years go by, we encounter fewer and fewer new experiences—both because we have already accomplished a lot and because we become slaves to our daily routines. For example, try to remember what happened to you every day last week. Chances are that nothing extraordinary happened, so you will be hard-pressed to recall the specific things you did on Monday, Tuesday etc.

What can we do about this? Maybe we need some new app that will encourage us to try out new experiences, point out things we’ve never done, recommend dishes we’ve never tasted and suggest places we’ve never been. Such an app could make our lives more varied, prod us to try new things, slow down the passage of time and increase our happiness. Until such an app arrives, try to do at least one new thing every week.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My daughter recently persuaded me to start eating two cloves of garlic every day. I feel more energetic and less stressed. Is it the garlic, or is it a placebo?

—Yoram

I am not sure, but have you considered the possibility that the reason you feel so much better is that people are now leaving you alone?

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

“A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior,” Take 2

You make decisions all the time. What should you eat for breakfast? Which route should you take to work? How much are you willing to pay for local, pasture-raised beef over factory farmed, corn-fed meat? Should you go for a run, jog, walk, or finish watching the last season of Breaking Bad?

Some of these decisions might be great, while others … not so much. For example, take the mind-boggling case of someone winning a chess championship one minute and texting while driving the next. Playing chess (competently, at least) requires thinking many steps ahead, considering multiple scenarios and outcomes — whereas texting while driving is a complete and utter failure of the same kind of forward-thinking. The gap between how amazing we are in some respects and completely inept in others just highlights the invaluable nature of studying how humans think and interact with the world.

So, when do we make good decisions, and when and why do we fail? Fortunately, behavioral economics does have some answers. In “A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior,” you will learn about some of the many ways in which we behave in less than rational ways, and how we might overcome some of our shortcomings. You’ll also find cases where our irrationalities work in our favor, and how we can harness these tendencies to make better decisions.

You will explore topics such as our “irrational” patterns of thinking about money and investments, how expectations shape perception, economic and psychological analyses of dishonesty by honest people, how social and financial incentives work together (or against each other) in labor, how self-control comes into play with decision making, and how emotion (rather than cognition) can have a large impact on economic decisions.

All of this, packed into just 8 weeks! Join our modern crusade to improve decision making, and hopefully learn some things on the way. Sign up now (class starts on March 11th): https://www.coursera.org/course/behavioralecon

Irrationally Yours,

Dan Ariely

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like