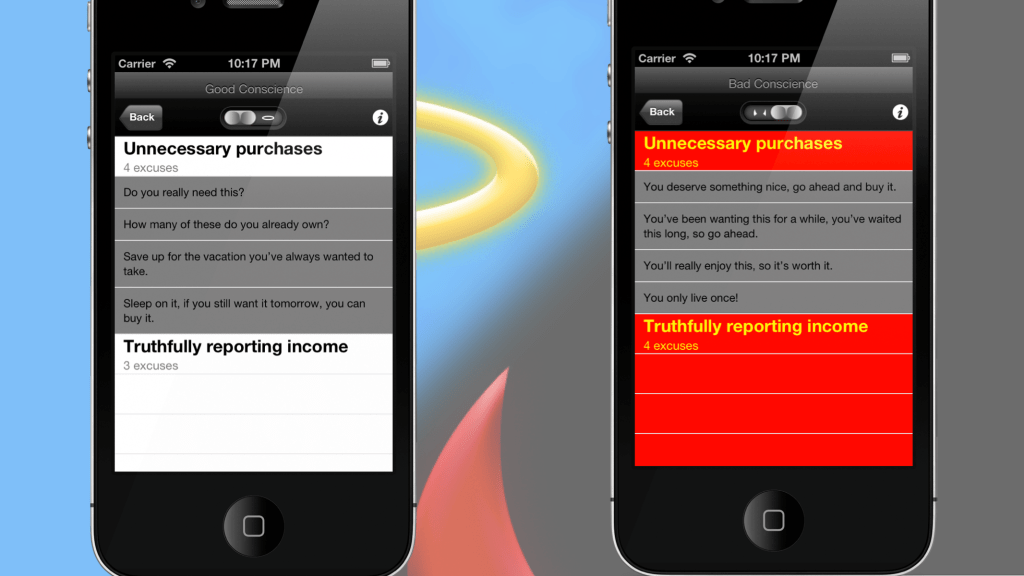

I’m pleased to announce that I have a new app available at the App Store called Conscience+.

Conscience+ helps you reason through moral dilemmas by providing you with little “shoulder angels” that can help you argue either side of a decision. Simply flip the switch at the top of the app to move between good conscience and bad conscience. Whether you need the extra push to go through with a selfish deed or words of wisdom to resist a bad temptation, Conscience+ has you covered.

- turning away the dessert menu

- splurging on a new electronic gadget

- staying faithful to your romantic partner

- padding your expense report on your boss’s dime

- lying on your college application

- and much, much more!

Get Conscience+ free from the App Store here! Once you’ve played with the app yourself, let us know in the comments if you have any suggested excuses. If we like them, we’ll put them in the next update.

This week, I visited a camera store to order two enlarged prints as a gift. I don’t order photo prints very often; in fact, I’m not sure that I have ever ordered prints aside from graduation photos. As I was making my purchase, the friendly, middle-aged woman who had been helping me asked whether I wanted to become a store “member.” I learned that for only 13 dollars and change, I could save 10% on purchases at the store for the next year, including around five dollars on the order I was purchasing. (I asked whether this discount applied to cameras. It did not.) After fleeting consideration, I explained that I did not think it was likely that I would be buying more prints in the next year, and hence membership was not a worthwhile purchase for me.

This week, I visited a camera store to order two enlarged prints as a gift. I don’t order photo prints very often; in fact, I’m not sure that I have ever ordered prints aside from graduation photos. As I was making my purchase, the friendly, middle-aged woman who had been helping me asked whether I wanted to become a store “member.” I learned that for only 13 dollars and change, I could save 10% on purchases at the store for the next year, including around five dollars on the order I was purchasing. (I asked whether this discount applied to cameras. It did not.) After fleeting consideration, I explained that I did not think it was likely that I would be buying more prints in the next year, and hence membership was not a worthwhile purchase for me.

To the friendly saleswoman, this did not seem be a satisfactory answer. She continued to push the membership offer, emphasizing the five dollars that I would be saving. “I don’t know about you,” she said, “but I’m someone who likes saving money.”

As I walked from the camera store to my car, I couldn’t help but contemplate this saleswoman’s comment. Did she actually believe that purchasing a camera store membership would benefit my bank account in the long run (as she appeared to), or was she simply a loyal store representative, eager to make additional sales (which seemed more likely)? Either way, her comment reflected a “save by spending” mentality that permeates modern-day America.

Membership programs and customer reward programs that charge an initial fee are prime examples of the “save by spending” creed. The customer is presented with various opportunities for future discounts, provided he or she coughs up money for a membership. As in my camera store situation, the membership offer is usually presented right before purchase, and the amount saved on the purchase itself is highlighted by the salesperson. The customer is forced to decide on the spot whether he or she would like to join.

Membership programs are rather curious in light of the established research finding that, in general, people will settle for less money if they can have it immediately – a tendency psychologists refer to as temporal discounting. (Think Money Mart loans or pawnshops.) In contrast, joining a membership program means foregoing money now for the possibility of earning that money back later on.

There are several reasons these programs may work. First, they force the consumer to project the likelihood of future purchases in a biased setting. People are notoriously bad at predicting the future; when buying an enticing summer novel at Barnes and Noble, surrounded by other books, one is more likely to consider spending money on books than on the variety of other products out there. Second, when presented with the membership program, people may experience mild social pressure from the sales associate. Third, if people are making their purchases with credit cards, they’ll be more willing to slap on an additional membership purchase; research attests that using credit cards makes people spend more, compared with cash.

Last but not least, the feeling of saving money is just plain rewarding. We know that money is valuable. At the same time, we don’t want to save by foregoing that sparkly new iPhone accessory. Membership programs offer us the opportunity to have our cake and eat it too – to experience the joys of saving and spending at the same time. And I’m guessing this makes companies pretty happy too.

Of course, membership programs aren’t the only example of our tendency toward saving by spending. Who hasn’t relished in the experience of buying a product at 50% off, focusing on that 50% that they have magically “earned”? I know I have. This may be part of the reason that the average American has half as much personal savings as personal debt.

Thank you, kindly saleswoman, but I will simply pay for my photo prints this time.

~Heather Mann~

MONDAY, JUNE 4 NEW YORK

Barnes & Noble @82ND and Broadway @7:00pm

THURSDAY, JUNE 7 CAMBRIDGE, MA

Brattle Theater @6:00pm

SATURDAY, JUNE 9 WASHINGTON D.C.

Politics & Prose @1:00pm

MONDAY, JUNE 11 SAN FRANCISCO

The Booksmith @7:30pm

TUESDAY, JUNE 12 PALO ALTO

Oshman Family JCC @7:30pm

THURSDAY, JUNE 14 LOS ANGELES

Live Talks Los Angeles @7:45am

For tickets: www.livetalksbusiness.com

FRIDAY, JUNE 15 SEATTLE

Town Hall @6:00pm

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 20 ST. LOUIS

St. Louis County Library Headquarters @7:00pm

FRIDAY, JUNE 29 DURHAM

Regulator Bookshop @7:00pm

TUESDAY, AUGUST 14 RALEIGH

Quail Ridge Books @7:30pm

Why We Lie (from the WSJ)

We like to believe that a few bad apples spoil the virtuous bunch. But research shows that everyone cheats a little—right up to the point where they lose their sense of integrity.

Not too long ago, one of my students, named Peter, told me a story that captures rather nicely our society’s misguided efforts to deal with dishonesty. One day, Peter locked himself out of his house. After a spell, the locksmith pulled up in his truck and picked the lock in about a minute.

“I was amazed at how quickly and easily this guy was able to open the door,” Peter said. The locksmith told him that locks are on doors only to keep honest people honest. One percent of people will always be honest and never steal. Another 1% will always be dishonest and always try to pick your lock and steal your television; locks won’t do much to protect you from the hardened thieves, who can get into your house if they really want to. The purpose of locks, the locksmith said, is to protect you from the 98% of mostly honest people who might be tempted to try your door if it had no lock.

We tend to think that people are either honest or dishonest. In the age of Bernie Madoff and Mark McGwire, James Frey and John Edwards, we like to believe that most people are virtuous, but a few bad apples spoil the bunch. If this were true, society might easily remedy its problems with cheating and dishonesty. Human-resources departments could screen for cheaters when hiring. Dishonest financial advisers or building contractors could be flagged quickly and shunned. Cheaters in sports and other arenas would be easy to spot before they rose to the tops of their professions.

But that is not how dishonesty works. Over the past decade or so, my colleagues and I have taken a close look at why people cheat, using a variety of experiments and looking at a panoply of unique data sets—from insurance claims to employment histories to the treatment records of doctors and dentists. What we have found, in a nutshell: Everybody has the capacity to be dishonest, and almost everybody cheats—just by a little. Except for a few outliers at the top and bottom, the behavior of almost everyone is driven by two opposing motivations. On the one hand, we want to benefit from cheating and get as much money and glory as possible; on the other hand, we want to view ourselves as honest, honorable people. Sadly, it is this kind of small-scale mass cheating, not the high-profile cases, that is most corrosive to society…..

For the rest of the article, please see the WSJ

As many of you know, I’ve recently been working on a new book. In fact, many of you helped me pick the title!

Well, I’m excited to announce that The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone — Especially Ourselves will be released in just a couple weeks on June 5th.

With new scandals popping out almost every week, and with substantial conflicts of interests in financial services, medicine, and government – understanding what makes us honest and dishonest is more important than ever.

Since many of you have been following me a long time, I want to offer a special invitation to my fans that pre-order the book

For the first 1000 people that pre-order a copy of The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty, you’ll receive exclusive access to a special hour long live webinar where I’ll discuss the ideas in my new book, give you a sneak peak at the content and even open it up for some Q&A.

If you’d like to join me, here are the 2 simple steps:

1. Purchase the book at any online retailer and in any format:

![]()

![]()

2. Forward the receipt you receive from your retailer to arielypreorder@gmail.com

I look forward to having you and hearing your feedback on The (Honest) Truth.

I just received this letter from a friend in the banking industry. He prefers to remain anonymous (you’ll see why soon enough).

Dear Mark,

There’s been a lot of ballyhoo recently about your IPO and your choice of investment bankers. Indeed, a war was fought by the banks to win your “deal of the decade.” As reported in the press, the competition was so intense banks slashed their fees in order to win your business. Facebook is “only” paying a 1% “commission” for its IPO rather than the 3% typically charged by the banks.

Congratulations, Mr. Zuckerberg! On the surface it appears your pals in investment banking have given you a quite a deal!… Or have they?

Let’s take a closer look and see what you’re getting for your money.

To start, your bankers have the task of selling 388 million Facebook shares to the public. In return, these banks will receive $150 million for their efforts. Morgan Stanley will get the largest share of that amount—approximately $45 million. But is $45 million all that Morgan Stanley makes off your deal?

Before we answer this question, let’s first dissect the sales pitch that Morgan Stanley probably gave you to justify “only” the $150 million fee. We’ll look at what they told you, and then what that actually means.

1) We will raise the optimal amount of money for the company, for our 1% fee. (Translation: How great is it that Zuckerberg believes he got a great deal by getting us down to a 1% fee! We can’t believe he got hoodwinked into agreeing to any level of what are actually variable commission fees.)

2) The definition of a successful deal is having a good price “pop” on the first day of trading. This will make all parties happy and you, Mark, look like a rock star. (Translation: No one benefits more than us if Facebook’s share price rises significantly on day one. That first day price “pop” will take money directly out of your pocket and puts it in ours and those of our “best friends”—not yours or the public stockholders. We will, at almost all costs, make this happen.)

3) This is a very complicated process, especially for such a large company, but we are here to successfully guide you through it. (Translation: It actually takes the same amount of work to do a large IPO as a small one. Thus for approximately the same amount of work we’re doing for Facebook, we sometimes get only $10 million—$140 million less than we’re making on Zuckerberg’s IPO.)

4) We will perform due diligence on your company to make sure the business and its finances are as they seem. (Translation: While it certainly does take some time and effort to perform reasonable due diligence, Facebook is a very large and well-known company, and we have done this same procedure hundreds of times.)

5) We will write a prospectus that outlines Facebook’s strategy, business plan, financials, and risks, and we will get it approved by the SEC. (Translation: Per the regulatory guidelines, a prospectus is largely a boilerplate document; for the most part, it’s just a lot of cutting and pasting.)

6) Once this prospectus is completed and with input from the Facebook team, we will come up with “the range” or the approximate price we think your IPO shares should be sold at to the fund managers. (Translation: The price of your IPO will be determined by where and how we can best optimize our (secret) profits on the deal.)

7) We believe the best shareholders are large fund managers, as they will become long-term holders of Facebook stock. However, at your request, we will allocate 25% of the IPO shares to sell to individual investors. (Translation: There are 835 million Facebook users worldwide. One could argue that what is best for Facebook would be to let all of Facebook’s legally eligible customers enter orders to buy Facebook stock. Then through the broker of their choosing, they could enter the quantity of shares they want to buy and the price they want to pay, just like the fund managers do—or are supposed to do. More on this scenario below.)

8) Our 10-day sales process will begin. For this important “road show,” you will be introduced to our large fund manager clients. These fund managers will receive our pitch for why they should buy your stock, and we will assess their interest and at what price. (Translation: Far from being long-term holders, many of our large fund manager “best friends” will, as soon as Facebook shares start trading, sell (or “flip”) for a windfall profit on all the underpriced shares we’ve given them. We’ll enable this by creating a perceived “feeding frenzy” for the stock by putting out an artificially low initial estimate ($28 to $35 per share) for where we think the IPO will be priced. We will then raise that estimate during the road show. Rumors about this begin to circulate over the next day or so.)

9) At the end of the road show on the night before the IPO, we will review the overall supply and demand for the stock and then “price” the shares. This is the price at which the large fund managers will receive their “winning” Facebook shares. (Translation: The price of the stock is already known. For the past few years, Facebook shares have been actively trading on such venues as SecondMarket and SharePost.)

10) And finally, we will put a mechanism, called a Greenshoe, in place that “supports” your share price after the IPO. (Translation: Thank God Zuckerberg doesn’t understand one of the greatest investment banking profit enhancing creations of all time—“The Greenshoe.” The Greenshoe will likely be our most profitable part of this deal. It’s a secret windfall, and although we market it to Facebook as a method to stabilize its share price, it’s really just another way for us, with little effort, to make huge amounts of money.)

We’re not done yet, Mark. Now, I’d like to dig a bit deeper into what’s going to happen and show you all the additional ways your banker friends and their large fund manager clients are going to make oodles of money off your deal.

1) Morgan Stanley only gives Facebook shares (“golden tickets”) to their best client “friends.” In other words, it’s no coincidence that Morgan Stanley’s biggest fund manager clients get the bulk of the shares offered in this kind of deal.

2) How do you become best friends with Morgan Stanley? There are lots of ways, such as trading tens of millions of shares with them or using the firm as your prime broker.

3) I’m sure there are a lot of conversations going on right now between Morgan Stanley’s salespeople and their clients. These conversations are probably along the lines of (wink-wink) “before we allocate our Facebook shares, we’d like to ask first if you plan to do more trading with us over the next week to six months….”

4) Let’s assume that 50 of Morgan Stanley’s “best friends” trade an extra 2 million shares so they can get access to more shares of the Facebook IPO. Let’s also assume that the average commission these clients pay to Morgan Stanley is 2 cents per share. Well, those extra trades will dump an additional $2 million dollars into Morgan’s coffers.

5) Now comes the part where Morgan Stanley actually gives free money to its friends. If the Facebook IPO is like the majority of other recent Internet offerings, here’s what Morgan Stanley will likely do. They know Facebook will be a “hot” deal. Especially, with all of the “5% orders” coming in, there will be huge demand for Facebook shares. My prediction is that Morgan Stanley will “price” Facebook at approximately $40 per share. This is the price at which Morgan Stanley’s “best friends will be able to buy the bulk of the 388 million shares offered.

6) Now let’s now assume that Facebook shares open for trading at $50—a lower percentage premium than Groupon’s opening share-price “pop.”

7) Let’s assume that one of Morgan Stanley’s “best friends” decides to sell 3 million shares right after the opening at $50 per share. That “best friend” will instantaneously make a $30 million profit. That’s right, a $30 million profit.

8) Here’s a question for you Mark. If Morgan Stanley’s “best friends” are selling Facebook shares at $50, who’s buying them? The answer is your “friends,” individual investors, most of whom are your customers.

9) Now for the final insult—the Greenshoe. Technically speaking, the Greenshoe gives your investment banks a 30-day option to purchase up to 15% more stock from Facebook than was registered and sold in the IPO. In layman’s terms, this means that, over the next 30 days, your “best friends” at the investment banks are able to buy approximately 50 million of your shares at $40 per share.

10) As in our example above, let’s say Facebook shares do trade at $50 soon after the IPO. Now I am a simple person, but if I were given the opportunity to buy something at $40 that I could immediately sell at $50, I would do it all day, every day…. And so will the investment banks. The Greenshoe actually gives these banks the ability to do this for 50 million of your shares.

11) So let’s assume that Morgan Stanley and its other banking “friends” buy 50 million shares at $40 per share and then sell these shares at $50. Morgan Stanley and its banking “friends” will make an additional $500 million- yes, $500 million- a HALF BILLION DOLLARS off your company.

So let’s now do a tally to see how much money all of your banking friends are going to make just for the privilege of doing your IPO. Let’s also see where this money comes from.

“Discounted” fees/commission: $150 million

Greenshoe profits: about $500 million

Extra trading commissions from large fund managers: approximately $10 million

—————

Investment Bank Profits: $660 million

As the lead bank on your deal, Morgan Stanley is likely to get 30% of the overall take. This means that your closest investment banking “friend” will make a bit more than $200 million from your IPO.

Morgan Stanley and the rest of the investment banks involved will also make sure that their favorite fund manager client “friends” are given lots of free money. Assuming that these “friends” are given 75% of the total number of IPO shares, or a total of 291 million shares, and assuming that the stock does rise from $40 to $50, then these fund managers will collectively, in one day, make $2.9 billion dollars in realized or unrealized profits. That’s right, 2.9 BILLION DOLLARS.

Mark, by now you must be asking yourself the obvious question. “Where and out of whose pocket does this money come from?”

Well, just think of it this way… Let’s assume you own a very expensive piece of waterfront real estate, and you hire a broker to sell it for you. After exploring the market and after getting indications of interest, your broker advises you that $10 million would be a great price for your home. You meet with the potential buyers and decide to sell it for $10 million. After the $1 million commission you have to pay your broker, your net proceeds are $9 million. An hour later, you drive by the house and see your broker in the driveway shaking hands with some different people. You pull over to see what’s going on, and you find that the people you just sold the house to for $10 million are very close friends of your broker. To your dismay, you also find out that those friends just sold your (former) house to somebody else for $15 million.

The same exact game is going on here, Mark. You’ll be selling 388 million shares of Facebook stock in your IPO. A likely scenario is that your broker “friends” are telling you to sell your shares at $40 per share. You’ll take their advice and sell at $40 per share, and the buyers will be Morgan Stanley’s biggest fund management clients. By the time you drive around the block, these folks will have sold their shares at $50 per share. In other words, using the same real estate scenario, you’ll have sold something of yours for $15 billion that is really worth $19 billion. And for that “unique” privilege, you’ll be paying your “friends” at the banks $150 million as a fee.

Makes you wonder who your real friends are…

————-

End of letter

————-

I find the points that my (real life) friend makes here highly disturbing, but I suspect that they also fit with what we now know about dishonesty.

First, although there are many ethically questionable practices occurring here, it’s not clear that anything illegal is going on. Second, I think that while this banking industry’s IPO process is artfully designed in such a way that, although overall it’s good for the bankers and less so for the companies, no single individual believes he/she is doing anything wrong. Third, I also suspect that since this is such a common practice, the bankers most likely truly believe that mechanisms such as getting a first-day IPO “pop” is great for Facebook and that the Greenshoe is fact put in place to stabilize the Facebook stock price, and not simply to generate more windfall profits for themselves. Forth, they probably believe in their own definition of a “successful” IPO, which in their terms is one where the stock is priced at $40 and quickly trades up to $50. In the case of Facebook, this process simply redistributes $4 billion from Facebook to the banks and the large fund managers. For Zuckerberg and his team, I have to wonder whether the emotional value of a first day share price “pop” is worth $4 billion.

I am not sure about you, but I find all of this very depressing.

Irrationally yours,

Dan

It’s not a lie if…”

Based on George Costanza’s advice to Jerry Seinfeld:

THE LIST

1. It’s not a lie if you believe it.

2. It’s not a lie if it doesn’t help you.

3. It’s not a lie if it hurts you.

4. It’s not a lie if it helps someone else.

5. It’s not a lie if it doesn’t hurt someone else.

6. It’s not a lie if everyone expects you to lie.

7. It’s not a lie if the other person knows the truth.

8. It’s not a lie if nobody can prove it.

9. It’s not a lie if you don’t get caught.

10. It’s not a lie if you don’t need to tell another lie to cover it up.

11. It’s not a lie if you were crossing your fingers.

12. It’s not a lie if you proceed to make it true.

13. It’s not a lie if nobody heard you say it.

14. It’s not a lie if nobody cares.

Irrationally yours

Dan

Before television and the internet, political candidates had two primary means of getting their image out into the public: live appearances and campaign posters. And given the limited reach of the former, posters were a crucial element in political strategy. How else were candidates supposed to project an image of decisiveness and gravitas?

So when Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for governor of New York in 1928, his campaign manager had thousands of posters printed with Roosevelt looking at the viewer with serene confidence. There was just one problem. The campaign manager realized they didn’t have the rights to the photo from the small studio where it had been taken.

Using the posters could have gotten the campaign sued, which would have meant bad publicity and monetary loss. Not using the posters would have guaranteed equally bad results—no publicity and monetary loss. The race was extremely close, so what was he to do? He decided to reframe the issue. He called the owner of the studio (and the photograph) and told him that Roosevelt’s campaign was choosing a portrait from those taken by a number of fledgling artists and studios. “How much would you be willing to pay to see your work hung up all over New York?” he asked the owner. The owner thought for a minute and responded that he would be willing to pay $120 for the privilege of providing Roosevelt’s photo. He happily informed him that he accepted the offer and gave him the address to which he could send the check. With this small rearrangement of the facts, the crafty campaign manager was able to turn lose-lose into win-win.

This story reminds me of the famed trickster, Tom Sawyer, who duped the neighborhood boys into trading him toys and apples for the chance to whitewash a fence. When one of the boys taunted him for having to work instead of going swimming, Tom responded with all seriousness, “I don’t see why I oughtn’t to like it. Does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?” Then when the boy asked for a chance to try it, Tom hemmed and hawed until finally the boy said he would give up his apple for a chance to whitewash the fence. Once Tom had one taker, outsourcing the rest of the work to other boys was a snap.

I conducted a similar experiment in a class I was teaching on managerial psychology. One day, I opened my lecture with a brief reading of a poem by Walt Whitman, after which I informed the students I would be doing a few short poetry readings, and that space was limited. I passed out sheets of paper providing students with the schedule of these readings along with a survey. Half of the students were asked whether they would be willing to pay $10 to come listen to my reading; the other half were asked whether they would be willing to listen to my reading in exchange for $10. Sure enough, those in the second group set a price for enduring my poetry reading (ranging from $1 to $5). The first half, however, seemed quite willing to pay to attend my poetry reading (from $1 to about $4). Keep in mind that the second group could have turned the tables and asked to be paid for listening to my recitation, but they didn’t.

In all of these situations, people (the campaign manager, Sawyer, and myself) were able to take a situation of disadvantage or ambiguous value and spin it to their (my) advantage. Once Sawyer pretended to be unwilling to part with the privilege of whitewashing, other boys wanted it, because obviously Tom was hoarding all the fun. When I told my students that space was limited and gave a suggested price for the recitation, I created the idea that this was an experience they would definitely want to have (as opposed to the other group, to whom I insinuated that listening to my reading of Whitman might be less than enjoyable).

I think Twain summed this strategy up best when he wrote the following about Tom: “He had discovered a great law of human action, without knowing it – namely, that in order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain.”

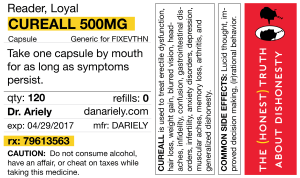

I’m excited to announce an innovative new therapy that will be released in tandem with my new book The Honest Truth About Dishonesty. I developed it with a team of medical doctors and behavioral economists to treat a broad spectrum of disorders. Cureall (Fixeverything) works to combat the tendency toward self-deception and dishonesty, which, like bacteria in the human body, affect everyone (some more than others).

Cureall is indicated for symptoms ranging from nervous headaches (which often result from faking our credentials to employers) to gastrointestinal disorders (a common side effect of seeing family and friends commit a dishonest act). Talk to your doctor about getting a prescription for Cureall, and watch as your lucidity, honesty, and energy levels go through the roof.

We’ve known for a while that both the processes and products of the pharmaceutical industry need to be regulated. The roots of this regulation stretch back over a century, but it’s been since the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments were passed in 1962 in response to thousands of severe birth defects caused by the drug thalidomide that drug manufacturers were for the first time required to prove the effectiveness and safety of their products to the FDA before marketing them. Since that time, we’ve created huge obstacles in terms of time, money, and evidentiary rigor between drug manufactures and the market; on average, it takes about 10-15 years and hundreds of millions of dollars for a drug to make it from the lab to the pharmacy. And as we come to a greater understanding about conflicts of interest and prescribing patterns, we also regulate the activities of pharmaceutical companies at even smaller level, such as when and to whom they can give pens or free lunches.

In stark contrast, we have the financial industry. In this domain, no one needs to prove the safety or effectiveness of financial products such as derivatives and mortgage-backed securities. This is because we make two major assumptions about such products based on economic theory: we presume first that they have sound internal logic and second, that the market will correct problems and mistakes if something goes awry with one of these new inventions.

In theory we could make the same argument for pharmaceutical products as well. Medications are also developed based on logic—in this case chemical and biological—and a group of experts assume that they will be effective based on this logic. We can also assume that the market would weed out bad medications, just as it weeds out unsuccessful companies and products. How would it do this? Well, people who take bad medications would become ill or die, other people would find out, and over time this process would preserve the demand for medications that work well—the same logic that is applied to financial products. Despite these parallels, there’s an incredible lack of symmetry in how we view regulating these markets.

People remain highly suspicious of one market (pharmaceutical), and far less so of the other (financial), but when we compare the systems in broad strokes, their similarities are evident. A paper I read recently got me thinking more about this comparison. In both cases, the industries in question get more money if people use more of their products, and both use salespeople to convey information about their products to consumers. So far that’s pretty standard fare in business. Less common is the similarity that these salespeople have incentives such that they benefit from selling the product, but lose nothing when it fails. Moreover, in both cases the product is complex and difficult to understand, even at the expert level. Additionally, there is substantial asymmetry in the knowledge of salespeople versus that of consumers. And in both cases, the stakes are very high, with physiological health and financial health in question. And while death rarely occurs as a direct result of financial products, the damage they can do is immense (see the financial crisis of 2008).

Yet we apprehend the dangers inherent in a free pharmaceutical market while remaining generally oblivious to those in the financial. No one protests along libertarian lines of letting pharma be free, or shouts from a podium that if the government just stayed out of our treatments and medications, amazing and innovative new cures would suddenly appear. Why then don’t we see the need to regulate the financial market?

I believe that one of the reasons for this discrepancy is that the casualties and damage done in the pharmaceutical domain are far more apparent. When things go badly in medicine, it’s easier for us to quantify them and make clear causal connections. Whereas in the financial market it’s generally the case that lots of people lose some money, but people rarely lose everything. Moreover, in the financial market, there are never just losers, there are always winners as well—someone will gain a lot from a losing transaction, and that’s frequently chalked up to how the system works. With pharmaceutical losses, the injury or death of patients far exceeds any gain the company might make (and then lose in litigation). Also, with medications, the counterfactual is generally much stronger. There are people who took a drug and those who didn’t, and often a clear comparison of the difference emerges. In economics it’s far more difficult to make a causal connection, after all, there is still debate over whether the first and second bailouts helped anyone other than the institutions that got paid directly.

Given the similarities between the markets, and the differences in how we tend to regard them, I think we need an FDA-like entity and process for financial products, because if we don’t have a counterfactual, we can’t compare and measure the value of their products. We could call it the FPA, for Financial Product Administration. One example of a financial tool that the FPA could test is high frequency trading. Companies are going all out to profit by being the fastest to buy and sell stocks, owning them for fractions of a second; they even go so far as to buy buildings closer to the stock market to make trading faster. The logic behind high frequency trading is that companies can take advantage of even tiny price fluctuations. And it’s possible that in principle they’re adding to the efficiency of the market, but it’s more likely that they increase volatility, and frighten people off the market, and therefore have a negative effect. It’s an understatement to say that this strategy is focused on the short term, whereas investment ideally is about a longer-term commitment. But regardless of one’s beliefs on whether high frequency trading is ethically sound, it would be nice to know for sure if it makes the markets better or worse off before allowing it.

By the way, one thing I appreciated most about the paper that inspired this post is that the authors are from the University of Chicago—home of the free market champions. That’s a departmental seminar I wouldn’t mind sitting in on.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like