At our lab, we’re interested in what kinds of tools people can use to make better decisions and reach their goals. When we decided to take part in this year’s Color Run, we tried to use some of these tools on ourselves to help us get in shape and ready for the race.

Like many people, we want to exercise more and get in better shape. Everyday temptation often gets in the way, though. To fight these temptations, we turned to one of the most prevalent behavioral tools: the “commitment contract.”

A commitment contract is an agreement your current self makes with your future self—you decide how you’re going to behave before temptations cloud your judgment.

In our lab, we had everyone agree to do some type of training three times a week in the six weeks leading up to the race. In the spirit of what we know about motivation, the focus was on concrete actions (spend a certain amount of time training) rather than vague outcomes (run a fast race).

“Some type of training” is pretty open-ended, so we each defined on our contracts what actually counted as a training session for us—this way we could all train to our own level while maintaining concrete goals. This is important because we all vary in how fit we currently are and how fit we ideally want to be. Research shows personal goals can be more success that striving after a single public standard. The standard becomes too high or too low for many people and leads to demotivation.

Commitment contracts are effective, but we decided to take the commitment up another notch by including social incentives. We each kept track of our training goals on a chart we posted in a very visible high traffic area – right by the kitchen!

The chart helped us track progress from person to person and week to week. The chart made our commitment (or lack of commitment) very visible to each other and ourselves. It’s painful enough to fail privately, but it’s even worse when everyone else can see us coming short of our own standards.

So, how did it work?

For the most part it worked fantastically. However, you can see that a handful of people fell off the bandwagon and never got back on. This is what behavioral economists playfully call that the “what-the-hell” effect.

Importantly though, about one-third of the team succeeded in completing all training sessions, and others were motivated to exercise more or harder than they did before.

It’s important to note that on average, exercise in the lab shot up and as a whole we moved toward our goal. Perfection with any intervention is not expected, but, as a group, we definitely made strides forward.

To better understand what was going on, I talked with some of our lab members to get their assessment.

For some of us, this was an all or nothing endeavor:

“Just knowing that I needed three stickers each week and would be anything less than perfect if I didn’t get all three got me to put on my running shoes without fail.”

Some people used the contracts and the process of defining what “counted” as a training session to eliminate the possibility they would take too much wiggle room:

“For me I always work out but sometimes I don’t feel so good and I ‘call it early’ and stop before getting a full workout. With the pre-commitment this didn’t happen. The fixed time goal kept me from quitting early.”

Other people used the contracts to build in wiggle room, just in case.

“I made my commitment contract loose enough that I could justify yoga or sex as exercise activities, but I never took advantage of the ample wiggle room.”

In the end, the training probably didn’t radically transform anyone from couch potato to athlete or yield dramatic before and after photos (nor did it exactly have randomized and controlled trials), but it seems safe to say that everyone got a little extra boost—even those who didn’t train. As one visitor to the lab remarked “You can’t look at all those smiley faces and not smile back.”

~Jamie Foehl~

Check out the photos we took from our run here, and for more research on how pre-commitment and social comparison affects goal pursuit check out these academic articles:

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I waste about two hours each day playing stupid games on my iPhone. It feels so innocent, but it actually makes me lose focus at work and takes up time I should be spending with my wife and kids. Do you have an idea for how I can ditch this bad habit?

—Arianna

One way to fight bad habits is to create rules. When you start a diet, for example, you can set yourself a rule such as “I won’t drink sugary beverages.” But to be effective, rules need to be clear and well defined. For example, a rule such as “I will drink only one glass of wine a day” is unlikely to work. With this type of rule, it is not clear what size of glass we are talking about, or if we can drink more today and reduce our drinking next week. In essence, if the rule is not clear-cut and unequivocal, we are likely to break it while deceiving ourselves that we are actually following it.

In your case, you could decide that, from now, on you won’t be playing the iPhone between 6 a.m. and 9 p.m. And to help you follow this rule, you should let your loved ones know. Or you could set up game bans for weekdays or working hours. Good luck.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am in middle school, and there is one topic in school I really love and one I really dislike. There is also one teacher I really love and one teacher I am not very excited with. Would I be better off if the teacher I love taught the topic I love, and the duller teacher taught the topic I dislike? Or would I be better off if the teacher I love taught the topic I dislike, and the duller teacher taught the topic I love?

—Tima

What you are really asking me about is the accumulation of pleasure and pain. On the one hand, you might argue that having one class with a great teacher and a great topic, and one class with nothing going for it, would give you at least one class to look forward to. You might also argue that, if a class isn’t going to be good, it doesn’t really matter how bad it is—adding a good teacher to a bad topic, for example, wouldn’t help much.

On the other hand, you might argue that a class with a bad teacher and a bad topic is going to be too much to bear. In this case, the combined pain might pass your tolerance threshold and color the entire semester.

I should say, first, that I am delighted you like some of your teachers and topics, and I don’t want you to stop thinking of school as joyful. But I do think that the mixing approach would be better for you.

I suspect that having a class with a bad teacher and a bad topic will be too much for you to handle. And I suspect that in the class with the teacher you love and the topic you don’t, you will learn to focus on the teacher and pay less attention to the topic, while in the class with the teacher you dislike and the topic you love, you will learn to focus on the material and pay less attention to the teacher.

I wish you many years of joyful (or at least not torturous) learning.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What do you think is the best psychological approach to getting over a girlfriend? Should you cut off seeing her completely? Continue getting together for coffee, etc.?

—Jason

I suggest that you cut it off completely. Meeting an old girlfriend over and over, while wondering if you should have ended things or not, is just going to prolong the pain—and without any real value.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

During my recent trip to New York City, I spent quite a bit of time sitting in taxis—taxis with ads that endlessly drill messages into your thoughts. I’ve never watched much TV, so my brain hasn’t evolved that uniquely American ability to tune out the mind-numbing commercials. As hard as I try, I just can’t look away when there’s a TV in sight.

As the commercials looped, one ad stood out to me and had me grinding my teeth each time it popped onto the screen. It wasn’t that it looked like an old-fashioned PSA, or because its protagonist donned a charmingly insincere Mr. Rogers smile. No—this ad grabbed me because of its heartbreaking ignorance of basic psychology. The goal of this ad was to get passengers to buckle up for safety, but its method was painfully misguided.

A number of strategies have been used over the years to get people to buckle their belts. For example, we have:

• Laws. This map shows the seatbelt laws in all US states, and according to the National Safety Council, seatbelt use is 13% higher in states with primary enforcement (meaning you can get stopped and ticketed just for not wearing a seatbelt) than those with secondary enforcement (88% versus 75%).

• Penalties. Although people are probably not thinking about the $69 fine they might have to pay or even the drivers license points they could rack up if they get caught, it is possible that some people may buckle up to avoid these consequences.

• Enforcement. Here, we’re talking about high-visibility enforcement such as checkpoints where all cars are stopped to check for seatbelt usage.

• Incentive awards for police officers to give tickets (ranging from small model cars awarded to individual police officers to much larger grants for police agencies).

• “Click it or Ticket.” This campaign has been particularly effective because it serves as a reminder of the immediate stakes (getting a ticket), even though they are smaller than the larger consequences (such as sustaining an injury in an accident). Reward substitution works. Fun fact: the campaign began in North Carolina, home of the Center for Advanced Hindsight, and was adopted by other states because of its success (most likely due to its catchy name).

• Safety belt reminder systems. These excruciatingly loud alarms get my passengers to buckle up in record time.

• Safety belt ignition interlocks. Some cars will refuse to start until all belts are in, although you can imagine why the idea hasn’t gained much traction.

• Education. Teaching children about seatbelt safety in school, while not an official persuasion method that I can find in any academic paper, has turned diligent recycling enthusiasts who just say no to drugs into relentless seatbelt reminder machines. I imagine that if our kids were the enforcers of just about anything, we would all be better off.

Some of these strategies work better than others, but none of them are actually detrimental to seatbelt compliance. And yet this taxicab ad, which I was forced to watch over and over in agony, conspicuously ignored what we know to be a primary motivator of behavior: social validation.

The ad gave one pivotal piece of information, which you can see in the accompanying photo: “60% of taxi passengers do not buckle up.” This kind of scare tactic is ineffective because it simply sends the wrong message.

Robert Cialdini has shown over and over again that social proof is an intoxicating principle of persuasion. We look to others to decide what to do, and when we are told about how most people behave in a given situation, we are likely to follow their lead. (This is why “word of mouth” can be so powerful, and companies pay top dollar to try and influence what their customers tell their friends.)

So, what message does this ad convey to cab riders?

This statement gives an implicit recommendation, noting that most people do not wear seatbelts. As social creatures, we look to others to determine how to behave in all kinds of situations, and riding in a taxi is no different. Rather than encouraging seatbelt use, this statement lets seatbelt-wearers know that they are in the minority while giving non-seatbelt wearers the comfort of knowing that their behavior is normal. It doesn’t matter why the majority doesn’t wear seat belts—whether it is uncool, unsanitary, too much of a hassle, or even unsafe—now they know that most people don’t do it, and that’s a good enough reason to go along with the flow.

If you want to persuade people to wear seatbelts, you should tell them that 84% of people in the US do wear seatbelts. Or you can further tap into group identity by noting that 90% of New Yorkers wear seatbelts.

It’s a shame that a message as important as “wear a seatbelt” could be so badly butchered. If companies have figured out how to use the concept of social proof to get people to spend more money, why can’t our safety promoters figure out how to use it to get us to make better decisions?

For a quick review of all six of Cialdini’s principles of persuasion (reciprocation, consistency, social validation, liking, authority and scarcity), see this article.

~Aline Grüneisen~

P.S. Some friends have informed me that you can simply turn off the taxicab TV. Noted for next time.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am the president of a local union that represents many federal workers. We are dealing with an interesting complaint stemming from the days during the government shutdown when employees were furloughed. Staffers who were furloughed are getting back pay for the days they were off, and because of this the employees who were designated as exempted from the furloughs (who originally felt special about their status and contribution) now feel gypped: Some of them expressed feeling like “a fool for working while others got to stay home.” Any advice?

—Robert

The current approach is clearly the wrong way to design paybacks after a furlough. Since we are likely to experience more government shutdowns in the years to come, maybe we should have a strategy for handling such situations.

I would suggest creating small groups composed of both furloughed and exempt employees and letting each furloughed worker decide how much of their back pay he or she is willing to contribute to the exempt workers in that group. A lot of research shows that people care to some degree about the welfare of others and about fairness, and we do so even at a cost to our own pocket. This kind of social utility should get the furloughed employees to act fairly, and they are even likely to be extra fair if the amount that they would give is going to be posted publicly and contribute to their reputation.

It’s possible that the government at some point will step in and do something to correct the issue. But while this local approach won’t completely fix the problem, it should make the distribution of income more equitable and, just as important, increase camaraderie among employees.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I love drinking good wine. Each time I go to a restaurant I wonder what is the ideal amount of money to spend on a bottle. What do you do?

—John

A recent experiment suggests an answer. Ayelet and Uri Gneezy from the University of California, San Diego, teamed up with a winery owner in their state to figure out, experimentally, the best price for his Cabernet. On some days they sold the wine for $10, on others for $20 or $40. Demand fell off at $40, but the winery sold more bottles of its Cabernet when the price was $20 than $10. On top of that, the customers who paid more indicated that the wine tasted better!

Uri and John List describe that experiment in their new book “The Why Axis,” in which they use field experiments as a method to look at many of life’s questions, from wine to love to the workplace. Their main advice is that we should all do more experiments.

So, the next time that you go to a restaurant, order two glasses of the same varietal of wine, one rather basic and one fancy, and tell the waiter to write down which is which and not to tell you. Then see if you can tell the difference. Of course, trying this experiment with just two wines is bad science, because you could be correct by chance, so you need to repeat the experiment many times. My guess? Your ability to tell the price difference will be indistinguishable from random guesses.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently watched your presentation at a professional conference and was wondering why an Israeli guy telling Jewish jokes is wearing an Indian shirt?

—Janet

In general I am not someone who should be asked for fashion tips, but this might be an exception. I like to dress comfortably, but in many professional meetings there is a code of uncomfortable dress: suits. My solution? I figured that as long as I am wearing clothes from a different culture, no one who is politically correct would complain that I’m underdressed. After all, the critics could be offending a whole subcontinent. Now that I think about it, maybe I should start giving fashion tips.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

I have been working on a documentary about cheating with Salty Features for a while now, and I am looking for the best title for the film. And who better to ask than you?

If you’d like to help me name this documentary, please take the survey here. It should only take you about 2 minutes to complete, and I very much appreciate your help.

Thanks!!

Irrationally Yours,

Dan Ariely

We all occasionally find ourselves paralyzed by looming decisions, unable to make up our minds with time running out. I was recently afflicted in just this way—I had no idea what to be for Halloween.

Costume ideas will usually just come to me, allowing enough time to prepare at a leisurely pace. I’d then confidently strut my way through Halloween parties full of friends in hand-sewn outfits with witty pop-culture references.

This year was different, though. My anxiety mounted as the big night approached and I had yet to pick a costume idea (let alone gather and assemble the required supplies). Before I knew it, it was the morning of the 31st and my Halloween-induced stress was at an all-time high. As the resident artist for the lab, my calling card is coming up with creative things.

Hundreds of ideas ran through my head, but everything was too difficult, expensive, or obscure. What to do?!

Fortunately, a friend directed me to a simple website which suggested a different nonsensical costume with each visit. Among the suggestions were ideas as disparate as “smutty rice cooker,” “exotic forklift,” and “immoral waffle.” Just a few quick clicks in and I knew what my Halloween costume would be: “The Salacious Rat King.”

Relief washed over me, and I began to mentally piece together my outfit. I could wear my sheepskin rug as a furry cape! I could make a mask from the box of desperately stale breakfast cereal! Suddenly, I was eager to go home and create my salacious rat king ensemble.

How did I go from immobilized by indecision to optimistic and enthusiastic about dressing up for Halloween in just a couple minutes?

By outsourcing my costume decision-making to a website, I was able to relinquish some responsibility over the outcome, lifting a weight from my shoulders. Instead of continuing to fret all day about my choices, the assistance of the costume-suggester gave me one humorous option at a time.

I no longer had to think, “What in the whole universe should I choose to assume as my identity for the night,” and instead, “am I more rakish ironing board or seductive mastiff?” This simplification of the process may have closed off some great costume options, but my enjoyment of Halloween was markedly increased once I accepted the computer’s suggestion.

In the end, my salacious rat king costume was a great success, and my Halloween was saved thanks to outsourcing my decision.

For more on the process of outsourcing decision making and the influence it has on stress and choice, we recommend this paper by fellow Duke Professor Gráinne Fitzsimons and this emotional TEDx talk by Stanford Professor and friend of the lab Baba Shiv.

~Matt Trower~

http://intl-pss.sagepub.com/content/22/3/369.full – paper

http://www.ted.com/talks/baba_shiv_sometimes_it_s_good_to_give_up_the_driver_s_seat.html

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A strange thing happened to me a few days ago. One of my employees came into my office holding a few lottery tickets and asked, “You in? It’s 45 bucks.” I never play the lottery, but I felt an inexplicable urge to say yes–and I did. Was I being grossly irrational?

—Itay

You were indeed irrational, but in a very common way. Usually, when you are considering whether or not to buy a lottery ticket, you take into account how your life would change if you won and contrast this with the cost of the ticket and the slim chance of winning. After making this quick computation, you decide not to buy a ticket.

But when another person asks you to “go half” with them on a tickets that they’ve already purchased, another factor comes into play: regret. Now you can’t help thinking how you would feel if that other person won. You quickly conclude that it would make you feel terrible and you also realize that you would keep on thinking about this forgone fortune for a very long time.

I think that too many people are currently losing too much money on various lotteries (often state sponsored), and I wouldn’t want more people to keep losing money this way. But if I were looking for a way to get more people to gamble, I would certainly try to play on our capacity for regret.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

On a recent flight, the attendants declared it was “Breast Cancer Awareness” month and asked for donations from the passengers for this worthwhile cause. I give to a multitude of breast-cancer organizations, but this approach offended me. Maybe if the airline had offered to match my contribution dollar for dollar it would have made me feel we were partnering in this effort, but the way it was handled just annoyed me. Is it just me or were they doing this the wrong way and actually hurting the cause they are trying to help?

—Rob

I suspect that many companies trying this approach to corporate responsibility don’t get much of a boost from it in terms of internal morale or customer loyalty. It turns out that companies get the most credit for donating to charity in two cases: One is when they give first and then tell the customers, “Look, we’ve already given on your behalf, now you can contribute as well.” The second is when they empower their customers to give themselves (“here is a $5 voucher for you to give to any organization you value”). The approach you describe, where the company simply says, “We have a charity that we like and want you to give to it,” is ineffective in every way.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

It seems to me that any reading of social science research implies that we are all less capable in making our own decisions and that as a consequence we need help. Yet, it seems that Americans are emotionally against any hint of paternalism. Any idea how we can overcome this barrier?

—Tom

I agree with your general position. I think that part of the problem is that, while we see irrationalities and bad decision-making in those around us, we don’t see these mistakes as readily in our own behavior. Because of this partial blindness, we are not as interested in limiting our freedom to make our own stupid decisions. I’m not sure what we can do to fix this part of the problem. But perhaps we can think about how to market paternalism in a better way. As a first step, I would change the term and call it maternalism. After all, who could object to listening to a mother figure?

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

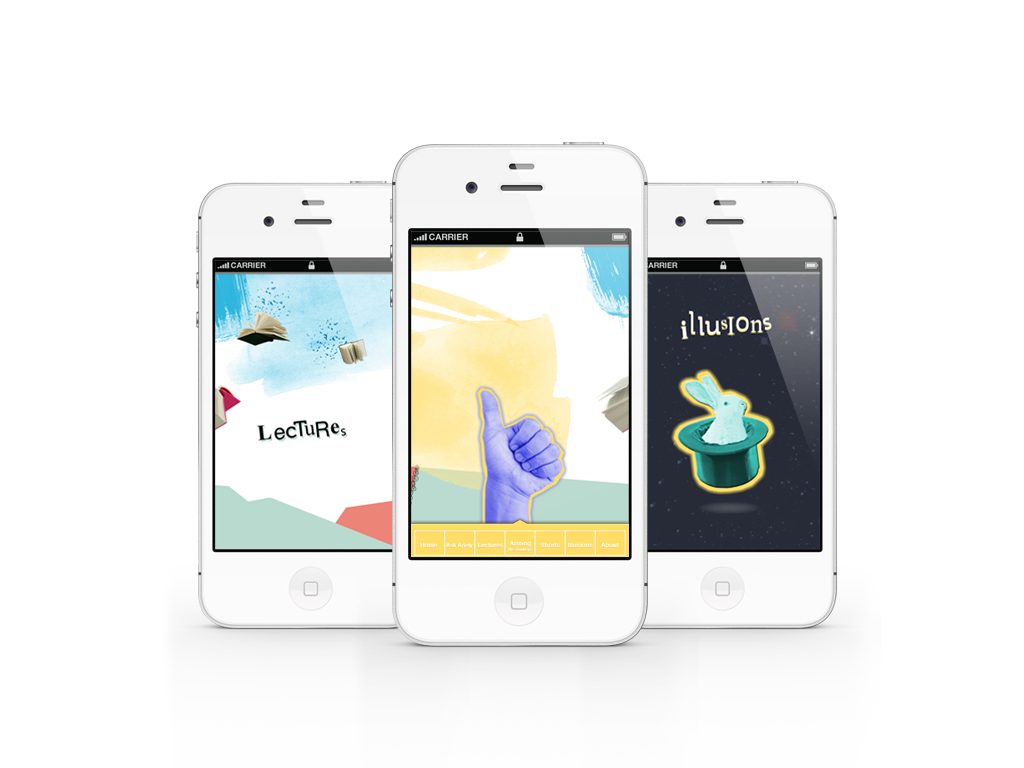

What can you do with Pocket Ariely?

READ! life-changing advice from a “genius at understanding human behavior” [James Surowiecki, staff writer at The New Yorker and author of The Wisdom of Crowds], and never make another bad decision!

WATCH! lectures and entertaining videos from “one of my heroes” [George Akerloff, 2001 Nobel Laureate in Economics], and never let anyone else make a bad decision either!

LISTEN! as a man described as “surprisingly entertaining” [USA Today] interviews the leading scientists of the day, and learn everything there is to know about humanity!

LOOK! at visual illusions that will twist your brain into knots, and remind yourself of your own irrational tendencies wherever you are!

TASTE! the culinary confections of a man widely acknowledged as the finest improvisational chef in three states, and never go hungry again! (Well, not really…)

With Pocket Ariely in your pocket, you can take me with you wherever you go. You’ll be happier (since you’ll never make another bad decision), healthier (since you’ll never make another bad decision), wealthier (since you’ll never make another bad decision) and wiser (yes, you guessed it: since you’ll never make another bad decision). We almost guarantee it!

Why spend $5 on an app? Think about how much you pay for one latte or one beer. Or how much money you waste on things you don’t need. Just think: you could improve your life forever by saving your lunch money and bringing a salad to work just once. Your waistline may thank you, too! But most importantly, think about how the purchase of this app will help the blossoming field of behavioral economics. All profits from this app will be put toward the research being conducted at my lab, the Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University.

Thank you in advance for helping our research, and I hope you enjoy what Pocket Ariely has to offer.

Irrationally Yours,

Dan

Watch our Pocket Ariely teaser and trailer, too!

Download now on your iPhone, iPad, and Android devices!

And check out the talented team of developers that made this app at mezzolab.com

Tomorrow (Tuesday, October 15 from 6-7pm), the Center for Advanced Hindsight will host a discussion on behavioral economics and applications in financial services. We are seeking partnerships with local financial services organizations that are interested in using behavioral-based strategies to help them better serve their mission. The attached Request for Proposals provides a summary of our proposed program. We will also be discussing the RFP on Tuesday and answering questions about the program.

The event is RSVP only. If you are interested in attending, please email rebecca.kelley@duke.edu

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like