![]() Recently, the “choose-your-ride” car (pictured here) has been roaming around downtown Durham and Duke University. The car seeks to reduce drunk driving by posing a choice between a $20 taxi or $1,000 fine. At first glance, this seems like a good strategy and it may indeed do some good. However, the car seems to missing one important element and it is the topic of Dan Ariely’s new book: morality.

Recently, the “choose-your-ride” car (pictured here) has been roaming around downtown Durham and Duke University. The car seeks to reduce drunk driving by posing a choice between a $20 taxi or $1,000 fine. At first glance, this seems like a good strategy and it may indeed do some good. However, the car seems to missing one important element and it is the topic of Dan Ariely’s new book: morality.

In “The (Honest) Truth about Dishonesty,” Ariely argues that morality matters. He explains how criminal behavior is not a simple cost-benefit analysis, and the threat of punishment only seems to work well when enforcement is nearly certain and extremely severe. Given that 300,000 of the Americans arrested for drunk driving every year are re-offenders, it seems that the threat and actual experience of consequences are not working so smashingly. Overall, drunk driving is rampant in the states. There are 900,000+ arrests a year. That’s arrest alone! The number of people driving drunk is much higher.

Drunk driving is not a niche offense; it is a social phenomenon that many see as a perfectly acceptable behavior. In movie The Hangover, Zach Galifinakas captures many American’s thoughts on drunk driving when he fondly remembers the night before and laughs it off saying, “Driving drunk, classic!” Many Americans simply feel no moral outrage with drunk driving, especially if they or their friends are the drivers. And what troubles me is that attempts like the “choose-your-ride” car do nothing to address this moral hole in the American conscience. According to Dan Ariely’s research on cheating, people cheat just as long as they can see themselves as good people. It’s no wonder people keep driving drunk, because society has done nothing to convince people that it is wrong.

Here are three specific ways this car fails to appeal to morality:

It makes it a choice. Think of other moral violations such as cheating in a marriage. For many, to even contemplate the idea of marital infidelity would be morally taboo. It should be the same with drunk driving. People engage in cost-benefit analyses for many actions, but when the action is in the moral domain this happens to a far lesser degree. When something is in the moral domain, hardline rules and concerns for one’s self-concept take over.

It puts a price on the crime. It turns a moral issue into a question of whether you want to pay $1,000 or if you can outwit the cops. According to the message sent by this car, you are not a bad person if you drive drunk. Instead, you are simply a person who is willing to pay a $1,000 fine.

It removes moral feelings. In chapter 9 of “The Upside of Irrationality,” Ariely discusses how thinking of situations like a math problem (rational thinking) can lead to less morality, because moral action is often driven by feelings. Here, the only feeling the car potentially activates is fear and the mathematical nature of the appeal might reduce any potential moral feelings people might have to begin with.

So what can we do?

Like with most socio-political issues, it is easy to criticize others’ solution and hard to put forth your own. Next week, I’ll attempt to put forth my own potential solutions to transform drunk driving into a moral issue. In the meantime, what do you think? Do you know people who chronically drive drunk? Can drunk driving be turned into something that is globally seen as morally detestable? If you have any solutions, ideas or articles you think would serve the blog, leave them in the comments and I’ll try to include them in part 2.

~Troy Campbell~

We lie. We cheat. We bend the rules. We break the rules. And sometimes, as we’ve seen in Greece, it all adds up. But, remarkably, this doesn’t stop us from thinking we’re wonderful, honest people. We’ve become very good at justifying our dishonest behaviors so that, at the end of the day, we feel good about who we are. This tendency is only getting worse, and, as innocent as it may seem, the consequences are becoming more apparent and more serious.

Cheating has less to do with personal gain than it does self-perception. We need to believe that we’re good people, and we’ll do just about anything to maintain that perception. Sometimes, this means behaving in ways that align with our sense of what is right. Other times, it means crossing that line, but turning a blind eye to our behavior, or rationalizing it in some way that allows us to believe it’s OK.

Let’s say your friend, who is not looking their best, asks you how they look, and you don’t want to hurt their feelings, so you lie. You fudge it. You don’t necessarily say, “Wow! You’ve never looked better,” but you don’t tell them the full truth. And you have no problem rationalizing your fib: It’s the right thing to do, because you would never want to hurt your friend’s feelings. Perhaps you used more neutral complimentary terms, or didn’t look them in the eye at that particular moment. These sorts of details would make it easier to justify your well-intentioned lie, and help you sleep at night without giving it a second thought.

The same kind of self-deception applies to wider-scale cheating, although the motivations are usually different. In more professional scenarios, our dishonesty is typically fueled by the desire for wealth or status rather than concern for the reputation of others. Greed is a powerful motivator.

About two months ago, American businessman Garrett Bauer was sentenced to nine years in prison for insider trading. Garrett was one of the people I had spoken to in researching the nature of dishonesty, and to see the consequences of his actions catch up to him that way was a brutal reminder of just how out-of-hand cheating can get. Garrett traded stocks on insider information for about 17 years. He started off small, as people tend to do, and never considered that he might get caught. As time went by, it got easier and easier for him to cheat the system free of guilt. But then he got caught, and now it’s too late to correct his mistakes.

That night, after his sentencing, I couldn’t sleep. I curled into the fetal position – the world looked terrible to me. I had spent the day before in New York giving talk after talk about cheating and dishonesty, how widespread they are, and how little appetite we have to start changing things. With all that cheating weighing on my mind, Garrett’s sentence was an additional terrible blow. It was overwhelmingly sad, and a very painful night.

The consequences of this sort of cheating are even more severe when the network of contagion is larger. We see this when we look at Greece, where masses of people have been cheating a little bit everywhere, and it’s added up. What this shows is just how contagious dishonesty can be. When we see somebody else cheat, especially if they’re part of our own, internal group, all of a sudden we figure out that it’s more acceptable to act this way. It’s not that the probability of our getting caught has changed – it’s that we’ve changed our mindset, convincing ourselves that the act itself is actually OK. At some point, you just think, “This is the way things are done,” and you go with the flow.

One woman from Greece recently told me that she was selling her apartment and she was considering whether to sell it legally (and pay taxes) or illegally (without paying taxes). She quickly recalled that she had bought it illegally, and that she was going to lose money if she would turn around and sell it legally – not to mention that in her mind she would be the only person in Greece paying taxes on real-estate property.

When everyone around you is cheating the system, what’s your motivation to be the one not playing along? And why change now? Why not make changes next month, or next year, instead?

This mentality is accentuated in Greece because it’s not just the everyday citizens who have been cheating – the government has been fudging the books. When cheating is that entrenched in a country, what can you do to stop it? It’s incredibly naïve to think that it will stop on its own. What Greece needs is something like the Reconciliation Act that South Africa adopted, focusing not on the travesties it has done to its people, but on starting fresh.

Every day, people are finding new and more creative ways to cheat, and to justify their dishonest behavior, regardless of the negative impact their actions might have on others. What’s most worrying about this trend is that we still fail to grasp the extent of our dishonesty. But it doesn’t have to be like this. If, on a global scale, we worked to understand the root of our dishonesty, and motivated each other to overcome it, we could do much better.

A Chinese tourist destination decided to experiment with offering free toilet paper, the Wall Street Journal reports. Rather than the usual procedure in China, where people bring their own toilet paper, in Qingdao they now encounter a toilet paper dispenser when they enter the public restroom (and, naturally, pass it again on the way out).

Now that the dispensers have been in the bathrooms for a month, it has become clear that visitors to Qingdao’s restrooms take an astonishing amount of care for their personal hygiene. Two kilometers (1.24 miles) of toilet paper disappear each day.

In this case, the excess T.P. use seems to reflect our findings with other forms of cheating and stealing: most people are cheating a little, rather than a few people cheating a lot. Of course, there are exceptions.

The toilet paper scenario meets the right conditions for people to cheat: they’ve got the opportunity and face no consequences for taking a bit extra, they can use the toilet paper later, and they can rationalize their behavior. They might tell themselves that the government is paying for their bathroom use in general, not only for that specific restroom; or that it’s expected that they’d take extra on the way out; or that they’ve already paid for it in the form of taxes; or that the government deserves what it gets. They’ve easily justified a way to walk out with wads of toilet paper and an untroubled conscience.

But why steal something like toilet paper?

One explanation probably has to do with the power of free. Maybe Qingdao’s bathroom users are so enchanted with the idea of FREE toilet paper that they would take it in any case, regardless of what they know about its value or usefulness.

Another explanation that pops up a lot with government-provided goods is the tragedy of the commons. The theory goes that individuals will use a limited resource (like commons for grazing animals) in an unsustainable way, so long as they get the full benefit and the harm is spread across the group. In the case of the toilet paper, the theory suggests that people use no more than they need when they have to pay for it individually. But when the cost is spread out across Qingdao, they are happy to overuse the resource. The usual prescription is to make individuals pay for the resource on their own—in other words, to go back to the days without free toilet paper.

But there might be a better solution. We can take research from behavioral economics to think of ideas that may be less strict than taking away the free toilet paper and, instead, simply push people toward lighter use of the product. How about replacing the landscape paintings above some dispensers with a picture of watching eyes—a tactic that has effectively encouraged people to clean up after themselves and pay on the honor system.

In Qingdao, restroom managers have attempted to confront their problem by posting a poetic reminder of social responsibility:

Convenience for you,

convenience for me,

civility is there for all to see.

My paper use, your paper use,

conservation is up to us.

The sign hasn’t had a noticable effect yet, but it may be on the right track. Reminders like the poem sometimes work (p.41, The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty) to keep people from stealing toilet paper. The Qingdao bathroom poets appeal to bathroom users’ social norms (“civility is there for all to see”) and allude to future benefits (convenience and conservation)—tactics that have been shown to work in getting people to wash their hands. But getting some sort of assent—like a signature—may be even more effective.

For example, bathroom visitors could sign in under a poem like this:

Future benefits and social obligations

Should outweigh your current temptations

You agree not to steal by signing below

You’ll take just what you need when you need to goSign here: _______________________

_______________________

_______________________

Of course, if the bathroom management is going to ask people to sign anywhere, they might also want to keep watch over the “free” pens.

~Susan Wunderink~

Plato once said that people are like dirt. They can nourish you or stunt your growth. This seems sage and reasonable, but I think people are more like Swiss Army knives (To be fair, Plato did not have the benefit of knowing of such a tool, so I don’t think I’m detracting from his comparison in the least). Swiss Army knives, as we all know, are incredibly versatile, and have a tool for almost any situation. Need to open a package—it’s got a knife! Sharing beers with friends on the beach—it’s got an opener! Have something in your teeth—there’s a toothpick for that! Need to do a little electrical work—it’s a got a tool that can strip wires! The downside is that Swiss Army knives are not particularly good for any specific purpose because any really intricate task is going to require much more specific tools.

People are a lot like Swiss Army knives from this perspective, and I am saying this with tremendous appreciation. A lot of the research in behavioral economists criticizes people for various ineptitudes: why we don’t save money, why we don’t exercise, why we text and drive. And it’s true, there’s a lot to criticize and a lot that goes wrong in our decision-making processes, but when you consider just how versatile we are, it’s very impressive. Essentially, we do a lot of things sort of OK. We can reason moderately well about money, we’re often pretty good with various relationships, we’re fairly moral, and most of the time we don’t kill ourselves or others. Not bad if you think about it this way!

Now, some people are more like the specialty tools, like post hole diggers, or lemon zesters, or cigar cutters; in these cases these individuals are truly excellent in certain domains. But often these people aren’t the best at navigating the world in a pragmatic fashion. There are often savants, like Kim Peek (the person that Rain Man is based on), who certainly can’t handle the day-to-day on their own, but have extraordinary abilities in other spheres. And plenty of geniuses have similar problems; take Bobby Fischer’s statelessness and detentions, or van Gogh’s famously self-detrimental tendencies and ultimate suicide. If everyone were like these folks, our species would surely be in peril. If people were all specialized, and could only think numerically, or long-term, or probabilistically, what would life be like? Neither rich nor long.

Of course these people provide inspiration and spur progress, and we admire and celebrate many of them (who don’t put their genius to antisocial use), but we should be grateful that most of us are more like Swiss Army knives.

We say that politicians are slimy, our noses wrinkling with disdain – but is that the way we like them? It seems the answer depends on whether we agree with their agenda.

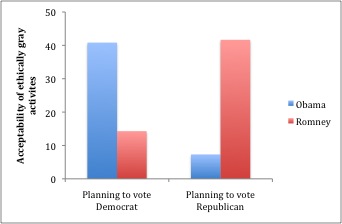

With the 2012 election steadily approaching, I wondered whether Democratic and Republican voters hold their preferred candidate and the opposing candidate to similar ethical standards.

To find out, Heather Mann (a graduate student working with me) and I conducted a little survey on American voters. Half the participants were shown a picture of Barack Obama, accompanied by the following paragraph:

“Sometimes, politicians engage in activities that are ethically ‘gray’ (e.g. providing favors to campaign donors, not fully disclosing information to the public, scheduling votes when politicians are away, etc.).

In your mind, how acceptable is it for Obama to engage in ethically gray activities in order to get elected and carry out his agenda?”

The other half of participants was shown a picture of Mitt Romney, and asked the same question about Romney’s ethical standards. All participants rated how acceptable it would be for the candidate to engage in ethically “gray” activities on a scale ranging from 0 (completely unacceptable) to 100 (completely acceptable).

Afterward, we asked participants whether they planned to vote for the Democratic or Republican candidate in the 2012 election. (Participants who indicated that they were voting for someone else or weren’t sure were excluded from our sample.)

What we found was that participants who were planning to vote Democratic indicated that Romney should be held to a fairly high ethical standard. Republican participants held a similar standard for Obama. But when participants happened to support the candidate in question – whether Obama or Romney – they indicated that ethically gray activities were approximately 3 times more acceptable.

This study harkens the age-old philosophical question: does the end justify the means? Judging by the results, it appears that Americans on both sides of the political spectrum feel that it does, at least to a degree. Democrats and Republicans alike are willing to allow for some shady tactics, provided those tactics advance their own ideals.

Politicians are in a bit of a bind. On the one hand, they are expected to uphold high ethical standards, while on the other hand, they are supposed to represent their voters. If voters hold a double standard for the ethical conduct of their own candidate and the opposing candidate, the overall standard of ethics is likely to fall to the lowest common denominator.

If politicians do get a bit “slimy,” are they the only ones to blame? Who are politicians accountable to, if not their voters? Finally, if the ethical bar is steadily lowered in the service of advancing party agendas, then who is responsible for raising it?

As part of the PoorQuality: Inequality exhibition that is currently on display at the CAH, we are showing a piece of art by Jody Servon entitled “I ______ a dollar.” This piece started out as one hundred $1 bills stuck flat against the wall. The bills hung there in a simple, uniform shape, Washington after Washington. The money was there for the taking, but only if you needed it. Jody asked viewers to think about the value of a single dollar, to contemplate their “needs” in relation to their “wants.”

“My hope is for people to actively consider whether or not having this single dollar will make a difference in his or her life, or if they feel the dollar is better left for someone else who needs it more. Perhaps the invitation to take free money will eclipse the question of want vs. need.”

A week went by, and one dollar disappeared. Afraid that the piece would dissolve too quickly, one lab member replaced the missing dollar. The art was whole again. More time went by, and another lab member needed change for the vending machine. So she took five singles and left her $5 bill. We treated the piece as if it was our own, moving bills around but preserving its integrity. The wall of money remained, for the most part, intact.

We asked Jody about her expectations for the piece.

“Among the scenarios I considered were one person swiping all of the dollars on the first day, the dollars slowly disappearing one-by-one, someone rearranging the dollars in a different design, or somewhat disappointingly, the piece remaining on the wall untouched.”

But the wall did not remain untouched, and one day it encountered a group of guests who came in on a particularly quiet day and left with most of the money. Sure, we were a little annoyed; our precious wall had been ransacked. But that was its purpose, and we laughed it off. At least we had a good story, right?

Some time later, one of the ransackers returned. This time, the CAH was bustling, full of people and lively conversation. He walked in, saw the commotion, and hesitated for just a moment before telling us that he was hungry. We don’t have any food here, but there are plenty of restaurants down the street, we told him. Of course, he was not asking where he could buy food. We knew that. But none of us jumped up to offer what was left of the money hanging on the wall. It was art, after all.

Here we were, hosting an exhibit on “inequality,” and there was no doubt that this man lay farther down on the distribution of wealth than any of us. And in all of our musings on the exhibit, never did we think that we might find ourselves faced with the perfect case of actual inequality.

Until this moment, we had primarily used and conceived of the wall of bills as a cashier. Yes, we contemplated whether we needed or simply wanted a dollar. But most of us don’t need a dollar. In the end, this experience may be the ultimate experiment of our project. And we stumbled into it unintentionally, or rather, he stumbled into our gallery.

A collaboration between Dan Ariely & Aline Grüneisen

The PoorQuality: Inequality Exhibit will be up until the end of August (and we will see whether there are any dollar bills left).Excuses. Justifications. Rationalizations. Stories. Stretching the truth… So many ways to whitewash the lies we tell ourselves and others. Here are a few questions that might remind you of your own dalliances with dishonesty.

1. What did you say the last time you were running late?

2. Take a look at your desk at home. How many pens and paperclips and so on did you “borrow” from work?

3. How accurate is your online dating profile? How accurate do you think others are?

4. Which e-mail threads would you delete if you knew someone was going to access your e-mail account?

5. Last time someone called you out for misrepresenting something, how did you explain it?

6. What questionable things have you done because “everybody else is doing it?”

7. Which line items on your resume are a bit of stretch?

8. What did you say the last time someone asked how much you weigh?

9. If you opened your mailbox and found a letter from the IRS informing you of an audit, how concerned would you be?

10. Have you ever told someone you never got their voicemail, text, or email?

11. What did you say the last time someone you don’t particularly like asked if you wanted to go to dinner or an event?

12. Speaking of dinner, have you ever said you enjoyed dinner at someone’s house when you didn’t?

13. What do you say when your dentist asks how often you floss?

14. How many haircuts have you claimed to like in the last year? How many did you actually like?

15. What should you be doing instead of reading this blog and answering these questions?

I’m going to start taking questions from you, dear readers, deeply ponder them, and send you my responses every other week in the Wall Street Journal.

Read this week’s column, A Double Dip for Voting?, right here. On voting, working, and new experiences.

If you have an interesting question for the column, please email me at: AskAriely@wsj.com

Our very own Troy Campbell presents his research on desensitization via repetition, and (naturally) uses Lady Gaga as his experimental stimuli.

Our very own Troy Campbell presents his research on desensitization via repetition, and (naturally) uses Lady Gaga as his experimental stimuli.

Related articles

- How Shocking Will Others Find Lady Gaga? (psychologicalscience.org)

When a certain former New York State Attorney General became New York Governor, he pledged to “change the ethics of Albany” and make “ethics and integrity the hallmarks of [his] administration.” Sure enough, he went on to fight collar crime and corruption, reduce pollution and prosecute a couple prostitution rings. Oh, but then the New York Times disclosed that this same law-and-order Governor was patronizing high-priced prostitutes. So much for changing the ethics of Albany.

Power and moral hypocrisy are not strangers – it’s one of the oldest stories around (generally going under the name of hubris), and we see it all the time. But why?

A few social scientists decided to take a stab at finding an answer. Joris Lammers and Diederik A. Stapel (from Tilburg University) and Adam D. Galinsky (from Northwestern University) ran five experiments addressing how morality differs among the powerless and powerful.

They simulated a bureaucratic organization and randomly assigned participants to be in a high-power role (prime-minister) or low-power role (civil servant). The prime-minister could control and direct the civil servants. Next, the researchers presented all participants with a seemingly unrelated moral dilemma from among the following: failure to declare all wages on a tax form, violation of traffic rules, and possession of a stolen bike. In each case, participants used a 9-point scale (1: completely unacceptable, 9: fully acceptable) to rate the acceptability of the act. However, half of the participants rated how acceptable it would be if they themselves engaged in the act, while the other half rated how acceptable it would be if others engaged in it.

The researchers found that compared to participants without power, powerful participants were stricter in judging others’ moral transgressions but more lenient in judging their own: “power increases hypocrisy, meaning that the powerful show a greater discrepancy between what they practice and what they preach.”

Joris and Adam hypothesized that this power-hypocrisy connection was due to the sense of entitlement that comes with positions of power. But what if you took away that entitlement by having participants view their power as illegitimate? In that case, the researchers posited, you would see the power-hypocrisy effect disappear.

To test their idea, they had 105 Dutch students write about an experience in which they were powerful or powerless. But half of the participants were asked to write about a time when they deserved their high or low power (it was legitimate), while the other half were asked to write about a time when they didn’t deserve their high or low power. They then had to rate the acceptability of the bike dilemma from above.

Results: when power (or lack thereof) was legitimate, the powerful also exhibited moral hypocrisy (being less moral themselves but judging others more harshly), while the powerless weren’t – just as before. But when power (or lack thereof) was illegitimate, the powerful didn’t show hypocrisy. In fact, the moral hypocrisy effect not only disappeared but was reversed, with the illegitimately powerful becoming stricter in judging their own behavior and more lenient in judging the others.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like