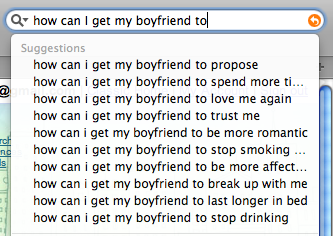

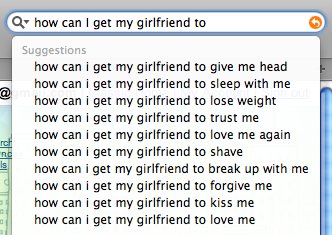

What boyfriends and girlfriends search for on Google

You know how Google sometimes “predicts” what you might be searching for by giving you a little drop down menu of suggested search queries? These suggestions, of course, are based on what other users frequently search. So I tried teasing out some gender differences. Look at the pictures below.

This shows Google’s remarkable power as a source of data on a range of human behaviors, emotions, and opinions. It gives us insights into what people might care the most about concerning a given topic. When people search a particular political leader, what are their main concerns? What are people secretly guilty about? For better or for worse, Google’s obsession with collecting and refining data has given us a window into each other’s fascinating and telling curiosities.

The Science Behind Exercise Footwear

A few weeks ago Reebok unveiled a walking shoe purported to tone muscles to a greater extent than your average sneaker. All you had to do was slip on a pair of EasyTone and the rest would take care of itself.

Exercise without exercise? Great!

Considering the abracadabra-like quality of the shoe, it’s no surprise that it’s been selling like hotcakes. The question of course is “ does it work”?

According to a recent New York Times article on the topic, Reebok has accumulated “15,000 hours’ worth of wear-test data from shoe users who say they notice the difference.” (The company also quotes a study as support, but it’s one they commissioned themselves and only carries a sample size of five.) The two women quoted in the article further echo this sentiment.

Reebok’s head of advanced innovation (and EasyTone mastermind), Bill McInnis, says the shoe works because it offers the kind of imbalance that you get with stability balls at the gym. Unlike other sneakers, which are made flat with comfort in mind, the EasyTone is purposely outfitted with air-filled toe-and-heal “balance pods” in order to simulate the muscle engagement required to walk through sand. With every step, air shifts from one pod to the other, causing the person’s foot to sink and forcing their leg and backside muscles into a workout.

But as the Times article proposes at the end (without explicitly using the term), the shoe’s success could instead come from the placebo effect. Thanks to Reebok’s marketing efforts, buyers pick up the shoes already convinced of their success, a mind frame that may then cause them to walk faster or harder or longer, thereby producing the expected workout – just not for the expected reason.

And there are some reasons to suspect this kind of placebo effect: In a paper by Alia Crum and Ellen Langer. Titled “Mind-Set Matters: Exercise and the Placebo Effect.” In their research they told some maids working in hotels that the work they do (cleaning hotel rooms) is good exercise and satisfies the Surgeon General’s recommendations for an active lifestyle. Other maids were not given this information. 4 weeks later, the informed group perceived themselves to be getting significantly more exercise than before, their weight was lower and they even showed a decrease in blood pressure, body fat, waist-to-hip ratio, and body mass index.

So, maybe exercise affects health are part placebo?

Irrationally Yours

Dan

P.S. If you’ve had the opportunity to try the shoe, leave a comment and let us know what you thought.

The Significant Objects Project

Would you pay $76 for a shot glass? What about $52 for an oven mitt? And $50 for a jar of marbles?

You may shake your head and say no way, but in a recent series of eBay auctions, the consumers did just that: they shelled out considerable cash for objects that to all appearances should never have fetched more than a couple bucks.

So what made the difference? Each item came with a unique tale.

The auctions were part of the Significant Objects Project, an experiment designed to test the hypothesis that “narrative transforms the insignificant into the significant.” Or, put differently, the goal was to determine whether you could take an object worth very little and make it worth much more by giving it a story, by endowing it with meaning.

To that end, the project’s originators – NY Times columnist Rob Walker and author Josh Glenn – bought up 100 unremarkable garage sale knickknacks for no more than a few dollars each, and then had volunteer writers whip up fictional back stories for them. This, they thought, would up the trinkets’ objective value.

They were right. Whereas the objects had cost Walker and Glenn a total of $128.74 to buy, the same trinkets netted a whopping $3,612.51 on eBay when paired with stories. This Russian figurine, for example, came with the original price tag of $3 but sold for $193.50. And this kitschy toy horse made the leap from $1 to $104.50. (See also:$76 shot glass, $52 oven mitt, $50 jar of marbles)

The results may seem surprising, but this is actually something we see all the time. It’s the basic idea behind the endowment effect, the theory that once we own something, its value increases in our eyes. (In one study, Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler (1990) randomly divvyed up participants into mug owners and buyers, and found that whereas owners requested around $7 for their mugs, the buyers would only pay an average of $3.)

But ownership isn’t the only way to endow an object or service with meaning. You can also create value by investing time and effort into something (hence why we cherish those scraggly scarves we knit ourselves) or by knowing that someone else has (gifts fall under this category).

And then there’s the power of stories: spend a fantastic weekend somewhere, and no matter what you bring back – whether it’s an upper-case souvenir or a shell off the beach – you’ll value it immensely, simply because of its associations. This explains the findings of the Significant Objects Project, and also how other things like branding works

Irrationally yours

Dan

The Psychology of Gift-Giving

Here it is again: holiday gift-giving season – the best win-win of the year for some, and a time to regret having so many relatives for others.

Whatever your gift philosophy, you may be thinking that you would be happier if you could just spend the money on yourself – but according to a three-part study by Elizabeth Dunn, Lara Aknin, and Michael Norton, givers can get more happiness than people who spend the money on themselves.

Liz, Lara and Mike approached the study from the perspective that happiness is less dependent on stable circumstances (income) and more on the day-to-day activities in which a person chooses to engage (gift-giving vs. personal purchases).

To that end, they surveyed a representative sample of 632 Americans on their spending choices and happiness levels and found that while the amount of personal spending (bills included) was unrelated to reported happiness, prosocial spending was associated with significantly higher happiness.

Next, they took a longitudinal approach to the topic: they gave out work bonuses to employees at a company and later checked who was happier – those who spent the money on themselves, or those who put it toward gifts or charity. Again they found that prosocial spending was the only significant predictor of happiness.

But because correlation doesn’t imply causation, they next took one more, experimental, look at the topic. Here, they randomly assigned participants to “you must spend the money on other people” and “spend the money on yourself” conditions — and gave them either $5 or $20 to spend by the day’s end. They then had participants rate their happiness levels both before and just after the experiment.

The results here were once more in favor of prosocial spending: though the amount of money ($5 vs $20) played no significant role on happiness, the type of spending did.

Surprised by the outcome? You’re not the only one: the researchers later asked other participants to predict the results and learned that 63% of them mistakenly thought that personal spending would bring more job than prosocial purchases.

Happy holidays

Dan

NYT Year In Ideas

The New York Times Magazine publishes once a year the “years in ideas.”

This is the third year in a row that they are picking one of my papers, which is very nice of them.

It is also particularity nice of them that this year they picked two papers I am a part of.

One of the papers they picked this year is: The Counterfeit Self

Her is their report:

Wearing imitation designer clothing or accessories can fool others — but no matter how convincing the knockoff, you never, of course, fool yourself. It’s a small but undeniable act of duplicity. Which led a trio of researchers to suspect that wearing counterfeits might quietly take a psychological toll on the wearer.

To test their hunch, the psychologists Francesca Gino, Michael Norton and Dan Ariely asked two groups of young women to wear sunglasses taken from a box labeled either “authentic” or “counterfeit.” (In truth, all the eyewear was authentic, donated by a brand-name designer interested in curtailing counterfeiting.) Then the researchers put the participants in situations in which it was both easy and tempting to cheat.

In one situation, which was ostensibly part of a product evaluation, the women wore the shades while answering a set of very simple math problems — under heavy time pressure.

Afterward, given ample time to check their work, they reported how many problems they were able to answer correctly. They had been told they’d be paid for each answer they reported getting right, thus creating an incentive to inflate their scores. Unbeknown to the participants, the researchers knew each person’s actual score. Math performance was the same for the two groups — but whereas 30 percent of those in the “authentic” condition inflated their scores, a whopping 71 percent of the counterfeit-wearing participants did so.

Why did this happen? As Gino puts it, “When one feels like a fake, he or she is likely to behave like a fake.” It was notable that the participants were oblivious to this and other similar effects the researchers discovered: the psychological costs of cheap knockoffs are hidden. The study is currently in press at the journal Psychological Science.

Could other types of fakery also lead to ethical lapses? “It’s a fascinating research question,” says Gino, who studies organizational behavior at the University of North Carolina. “There are lots of situations on the job where we’re not true to ourselves, and we might not realize there might be unintended consequences.”

The second paper they picked this year is: The Drunken Ultimatum

Her is their report:

The so-called ultimatum game contains a world of psychological and economic mysteries. In a laboratory setting, one person is given an allotment of money (say, $100) and instructed to offer a second person a portion. If the second player says yes to the offer, both keep the cash. If the second player says no, both walk away with nothing.

The rational move in any single game is for the second person to take whatever is offered. (It’s more than he came in with.) But in fact, most people reject offers of less than 30 percent of the total, punishing offers they perceive as unfair. Why?

The academic debate boils down to two competing explanations. On one hand, players might be strategically suppressing their self-interest, turning down cash now in the hope that if there are future games, the “proposer” will make better offers. On the other hand, players might simply be lashing out in anger.

The researchers Carey Morewedge and Tamar Krishnamurti, of Carnegie Mellon University, and Dan Ariely, of Duke, recently tested the competing explanations — by exploring how drunken people played the game.

As described in a working paper now under peer review, Morewedge and Krishnamurti took a “data truck” to a strip of bars on the South Side of Pittsburgh (where participants were “often at a level of intoxication that is greater than is ethical to induce”) and also did controlled testing, in labs, of people randomly selected to get drunk.

The scholars were interested in drunkenness because intoxication, as other social-science experiments have shown, doesn’t fuzz up judgment so much as cause the drinker to overly focus on the most prominent cue in his environment. If the long-term-strategy hypothesis were true, drunken players would be more inclined to accept any amount of cash. (Money on the table generates more-visceral responses than long-term goals do.) If the anger/revenge theory were true, however, drunken players would become less likely to accept low offers: raw anger would trump money-lust.

In both setups, drunken players were less likely than their sober peers to accept offers of less than 50 percent of the total. The finding suggests, the authors said, that the principal impulse driving subjects was a wish for revenge.

Lets see if this trend continues….

Visual illusions and decision illusions

Consider some of illusion at the bottom of the demo page (click here to see it).

The two middle color patches look as if they are different, but in fact they are exactly the same. What is gong on here? How can it be that we see wrong? How can it be that eve after we are shown that these two patches are identical we still can’t see them accurately?

It is because our brain is wired in a particular ways and this wiring, while very good for some things, is not perfect — and it makes us susceptible to certain errors and mistakes. Moreover, because these mistakes are a part of us, we are fooled by them in predictable and consistent ways over and over.

Now, vision is our best system. We have lots of practice with it (we see many hours in the day and for many years) and more of our brain is dedicated to vision than to any other activities. So consider this — if we make mistakes in vision, what is the chance that we would not make mistakes in other domains? Particularly in domains which are more complex (dealing with insurance, money, etc.), and ones in which we have less practice? Domains such as decision making and economic reasoning?

Not very high I think — and this is why we have lots of decision illusions. The predictable, repeated mistakes we all make in our financial, medical, and other daily decisions.

Irrationally yours

Dan

Late but maybe still useful

Here are a few suggestions I gave for eating less on thanksgiving:

1) “Move to chopsticks!” Or, barring that, smaller plates and utensils.

2) Place the food “far away,” so people have to work (i.e., walk to the kitchen) to get another serving.

3) Start with a soup course, and serve other foods that are filling but low in calories.

4) Limit the number of courses.

Variety stimulates appetite. As evidence, consider a study conducted on mice. A male mouse and a female mouse will soon tire of mating with each other. But put new partners into the cage, and it turns out they weren’t tired at all. They were just bored. So, too, with food. “Imagine you only had one dish,” he says. “How much could you eat?”

5) Make the food yourself. That way you know what’s in it.

6) “Wear a very tight shirt.”

Enjoy

Some reflections on money

Sex, Shaving, and Bad Underwear

Sex, Shaving, and Bad Underwear

Or how to trick yourself into exerting self-control

Recently, I gave a lecture on the problem of self-control. You know the one: At time X you decide that you’re done acting a certain way (No more smoking! No more spending! No more unprotected sex!), but then when temptation strikes, you go back on your word.

As I mention in Predictably Irrational, this predicament has to do with our inherent Jekyll-Hyde nature: We just aren’t the same person all the time. In our cold, dispassionate state, we stick to our long-term goals (I will lose ten pounds); but when we become emotionally aroused, our short-term wants take the helm (Oh but I am hungry, so I’ll have that slice of cake). And what’s worse, we consistently fail to realize just how differently we’ll act and feel once aroused.

Fortunately, there’s a way around the problem: pre-commitments, or the preemptive actions we can take to keep ourselves in check. Worried you’ll spend too much money at the bar? No problem, bring just the cash you’re willing to part with. Afraid you’ll skip out on your next gym visit? All right, then make plans to meet a friend there. And so on. Pre-commitments can take many a form, and some get pretty creative.

For example, I surveyed my audience at the lecture hall for their pro-self-control tactics, and I received two noble suggestions. One woman reported that when she goes out on a date with someone she shouldn’t bed, she makes a point to wear her granniest pair of granny underwear. Similarly, another woman said that when faced with that kind of date, she just doesn’t shave.

Both are great ideas, I think, and are likely to work — well they’re certainly better than only relying on the strength of your self-control — but there is a risk. Let’s say the woman with the ugly underwear finds herself uncontrollably attracted to her date and decides that, you know what, ugly underwear be damned, there will be sex tonight! Chances are she will wake up in the morning wishing she had worn her silk lingerie after all.

Irrationally yours

Dan

p.s if you have any personal self control stories that you are willing to share — please send them my way

Tiny Irrationalities That Add Up: Texting While Driving

Sad story out in the New York Times describing growing concerns about texting while driving. In Britain, a woman was sentenced to a 21-month sentence after it was found that she had been texting while driving, which resulted in the death of a 24-year old design student. In many ways, texting while driving illustrates a case in which tiny, individual irrational decisions can accumulate and cause widespread suffering, not only for the individuals who are texting, but their unsuspecting victims. Unlike cases of drunk driving, in which the driver’s decision making abilities are impaired, drivers who text are at their full wits to wait until they’ve pulled over to check their texts, and yet in the process they routinely underestimate the risk they impose to themselves and others.

Aside from being another example of a common irrational behavior (and who among us did not text or checked their email while driving), this leads me to wonder, what is the best way to solve this problem? While presently the issue is being hotly debated here in the US on a state-by-state basis, England has taken a tough national stance on texting while driving, which includes hefty minimum point penalties on the offending party’s license, and fines upward of 60P. If you watch the video in the linked article, you’ll also find a very graphic video depicting the carnage of a texting accident–shocking and informative public service announcements are yet another option. Alternatively, we can hope that cell phone companies are continuing to explore voice activation technologies that can read text messages aloud and also transcribe them from voice — thereby by-passing the problem altogether.

We have lots of irrational problems to deal with, and the realization that tiny, seemingly innocent little ones, like 10-second text messages, can cause so much damage should make us look around for more such problems. perhaps ones that are not as obvious (think health care), but are potentially just as damaging.

Irrationally yours

Dan

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like