(Sample) Size Matters: New App Release!

a research app for smartphone scientists on the go

Social science has uncovered many fascinating aspects of human behavior, from how we think as individuals to how we act in groups. We know that humans are loss averse, emotional, habit-forming creatures. We mispredict the future and misremember the past. And yet, what social science is missing is a better understanding of how these phenomena (and others) change over time, in different cultures and regions, across gender and age.

By collecting a heaping amount of data (and increasing the size of our samples), we hope to unravel nuances in behavioral variations; we hope to detect the impact of minor differences that simply wouldn’t appear in smaller samples. The pursuit of this app is to collect an abundance of data from an abundance of locations all over the world, shining light on behavioral similarities and differences, from Antarctica to Zimbabwe. To do this, we need your help! Join our team of smartphone scientists and take on small tasks that will be “pushed” to you through the app.

On some occasions, you’ll be asked to give your opinion about various topics; you may be asked to predict the outcome of an experiment or to record your thoughts on anything from wealth distribution to peer influence. On other occasions, you’ll be sent out into the world to collect data; you may be asked to interact with a stranger or observe a scene and record certain details. Prepare to be surprised and delighted by the exciting research you will be a part of.

Participate in a movement that transcends oceans and cultural barriers, gaining access to a wider range of information than ever before. Download the app now, and get started on your first mission!

How it Works

- create an account

- complete your first mission by following the directions in the app

- sit back and wait for the next mission to be pushed to you, and make sure to complete it before time runs out!

- keep track of your missions and your points earned for each task

Ask Ariely: On Tipping, Attachment, and Hoarding

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I work as a waiter in Waikiki, and sometimes to pass the time I conduct mini-experiments with customers, altering my behavior and attitude from day to day and seeing if it increases tips (in case you were wondering, seeming sad nets the most tips).

I have noticed that those paying with credit cards leave bigger tips, but it varies by card: American Express users tip the most, those with Visas a little less. Discover card users are by far the worst. I can’t quite figure this out.

—V

One possibility is that wealthier people get American Express cards, the less affluent Visa, and the least well-off Discover—and they tip accordingly. You should be able to test this hypothesis by looking at their spending patterns—for example, how much they spend on wine.

Another possibility is that credit cards have a priming influence. If a person takes out an American Express card and looks at it, its reputation as a premium card might make the owner feel richer and therefore more generous. These feelings would diminish with a Visa card and be present even less with a Discover card (which generally is of more modest repute).

My guess is that both of these hypotheses play a role in what you’ve observed. To be sure, we would need to experiment by having a group of people with multiple kinds of credit cards pay in similar situations using different cards. Then we’d see if and how they change their spending.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I work with many entrepreneurs in their early innovation stage and am always intrigued by the strong (irrational) attachment they develop to their idea, often leading to their being blind to reality and to wasting time and money. How quickly do we get irrationally attached to our ideas? Is it based on elapsed time or on specific actions we take (such as presenting the idea to others)? What can be done to cure this?

—Omer

The problem, of course, is not just with entrepreneurs. From time to time we all experience someone in a meeting who says something random, and not particularly smart, but then insists that we follow up on his or her brilliant suggestion.

A few years ago, Daniel Mochon, Mike Norton and I conducted experiments about what we called “the IKEA effect”: As the instructions to build something become more challenging and complex, we love even more what we have created. We also showed that this effect takes place rather quickly. In perhaps the most interesting and irrational part of the whole story, we found out that we also mistakenly think other people will share in our excitement over our inferior creations.

What can we do about this? We could try to create an environment where ownership is less powerful or less associated with particular individuals. But if we manage to reduce or eliminate the feeling of ownership, are we also eliminating commitment and motivation? Maybe we should try to increase this sort of proprietary attachment. (And by the way, now that I have finished, I love my answer and think that it is very insightful.)

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

After I’ve bought an expensive or limited-edition scotch, I worry about drinking the bottle too quickly or being unable to find more once it’s gone. So partly opened bottles in my closet keep accumulating. Any advice on how to enjoy my scotch rather than hoarding it?

—Jonathan

The problem with hoarding (collecting) is thinking about it as one decision at a time. I would either try to think about such questions from a broader perspective (“Would I be interested in getting 24 more bottles?”) or set up a rule for the number of bottles that you can have in your house at one time (let’s say 10). Then you’d have to finish a bottle or give it away before you acquire another.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Predictably Irrational App for iPad and iPhone

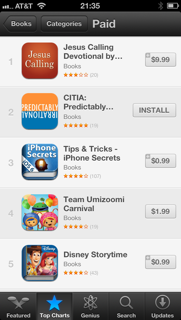

Thanks for downloading the PI app — you’ve brought it up to the #2 spot in iTunes!!

If you’d like to give the app a review in the app store, I’d very much appreciate it.

PI App On Sale (until Friday 6/7)

Hello friends,

This blog has turned into a great way to keep in touch with you — a persistently curious crew interested in the same Big Questions at the heart of my research: Why do we behave in the ways we do? Why do we do things that don’t always serve our best interests? What can we do to change?

As a small token of gratitude for your attention, we are dropping the price on the app edition of “Predictably Irrational” to $0.99 from now until June 7th (so, for the next 72 hours). The app offers up its own unique way to explore my research — a visual index of the book’s key ideas, with topics served up on slide-like “cards.” Makes for a neat new way to explore the book, whether you’ve already read it or not.

Irrationally yours,

Dan Ariely

Happy irrational birthday

Three years ago today was the publication date of “The Upside of Irrationality”

The book has 2 parts: the first is about motivation at work, and the other is about personal life (dating, happiness etc). Interestingly, in the last year I am getting much more interest from companies to do field research related to both of these domains, and this is leading to some new exciting findings on the psychology of labor and on dating….. More to come.

For now, Mazal Tov

Ask Ariely: On Happy Money, Splitting Bills, and Unintended Stalking

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have worked very hard for most of my life, and I am getting to feel more secure and comfortable. But I don’t feel as happy as I expected, given all my achievements and financial success. I am not one of those hippies who think that money is not important, but it feels like something is missing. What am I doing wrong?

—Matt

Don’t worry. The fact that your financial achievements have not brought you contentment does not mean that you’re a hippie. Social scientists have long been troubled by the finding that people basically think money will bring them happiness but it does so less than they expect.

There are two possibilities: First, that money cannot buy happiness. Second, that money can buy some happiness, but people just don’t know how to use it that way. The good news is that this seems to be the correct answer.

In their fascinating book “Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending,” Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton say there are two ways to get more happiness out of our money. The first is to buy less stuff and more experiences. We buy a sofa instead of a ski trip, not taking into account that we will get used to the sofa very quickly and that it will stop being a source of happiness, while the vacation will likely stay in our minds for a long time.

Second, and more interesting, Drs. Dunn and Norton demonstrate that we just don’t give enough money away. Which of these would make you happier: buying a cup of fancy coffee for yourself, buying one for a stranger, or buying one for a good friend? Buying a cup of coffee for yourself is the worst. Buying for a stranger will linger in your mind and make you happier for a longer time, and buying for a friend is the best—it would also increase your social connection, friendship and long-run happiness.

So money can buy happiness—if we use it right.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m going to an out-of-town concert next month with friends and, as usual, I ended up organizing everything, booking a hotel room and fronting the money. When I’ve done this with groups in the past, I always end up spending the most on shared expenses, because they are never divided up evenly.

Perhaps I’m afraid to ask for large amounts of money, even though these are the true expenses that should be shared by everybody. What can I do to make sure that the bill for this upcoming show is split fairly?

—Scott

This is a question, in part, of how much you care about splitting the expenses evenly and how much responsibility you’re willing to take to improve the situation. I assume you’re willing to take this responsibility, so I suggest that you collect money from everyone in advance and pay all bills from this pool of money (and add 20% just in case, because we often don’t take all contingencies into account).

This way, everyone will pay the same amount, and bill-splitting will never come up. If there’s extra money, keep it for next year, or buy everyone a small gift to better remember the vacation.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have sometimes found myself walking behind a woman at night in an unsafe place and going in the same direction. Even though there is some distance between us, I can feel the doubt and worry in her mind. How do I handle this situation? Should I stop or say something? I have places to be, too, but clearly I don’t want the woman to feel unsafe.

—Steve

Simply pick up your cell phone and call your mother. In the world of suspicion, nobody who calls his mother at night could be considered a negative individual.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

New book: Happy Money.

You know the pain of making a bad money decision, from small to large—remember that Living Social deal you never used, or the big house you thought you needed that turned out to be a money pit? Sure you do! But most of us don’t know how to spend money in a way that actually makes us happy, aside from the rush of novelty that quickly dissipates as the hedonic treadmill continues on. Well, allow me to present a new book from my friends Mike Norton and Liz Dunn, which will help you do exactly that. This is not your typical CPA make-and-save-money advice—this lays out well-researched advice for how to spend money in a way that improves your life as a whole. Who couldn’t use that?

In the mean time, here’s an Arming the Donkeys interview I had with Mike on this very topic.

Enjoy, and Happy Reading!

Ask Ariely: On Sealed Bids, Netflix, and Laughing at Your Own Jokes

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My parents are about to put their house on the market in Scotland, where there’s a system of setting an asking price and having interested parties make sealed bids. Any advice on how to get the highest sale price?

—Moses

In auctions there are usually two forces: what people think the starting price of a house should be and how intense the competition gets between the bidders over time. Establishing a starting price for the bidding, it turns out, has an opposite effect on these forces.

If you set a high starting price, there’s a good chance that people will start thinking about the house from that point and offer a higher bid. On the other hand, if you set a low starting price, more people will get into the auction, the competition will be fiercer—and the outcome is likely to be a higher final price. (By the way, have you noticed that in auctions—on eBay, for example—the person who pays for the item at the end of the auction is called “the winner”? This suggests that competition is indeed a very strong driver.)

So if you have a sealed-bid auction in which people can submit a bid only once, go with a high starting price. But if there are multiple rounds of bidding, think of the starting price as a lure for getting many bidders involved at the get-go.

Last week I met with a friend in San Francisco (let’s call him JC) who is house-hunting. He said that the houses he has bid for sold for about 30% to 40% more than the asking prices. The competition has been intense, the process very frustrating, which brings me to a final point: A bidding frenzy might be good for a seller, but since we are all going to be buyers and sellers at some point, it’s not clear that the overall market for housing is better off with this procedure.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am a longtime Netflix customer. Recently, Netflix removed about 1,800 movies from its service, while adding a few very good ones. I know I probably never would have watched those 1,800 movies, but I am upset and am seriously considering leaving Netflix. Why do I feel this way?

—Kristine

As a movie man myself, I appreciate your perspective. The basic principle at work here is loss aversion: the idea that losing something has a stronger emotional impact than gaining something of the same value. Even though the deleted movies were probably not that great and the current library of Netflix may be, objectively, much better, having movies taken away from you feels like a painful loss.

One way to think about this is to contrast new and old Netflix users. A new one would just look at the overall quality of the movie collection, which may be better than it used to be. For the old user, however, the current collection is just one part of the experience, while the loss of all those movies is another. As a result, the longtime member may be much less happy.

My suggestion is for you to try thinking about Netflix as a service that provides you not with particular movies but with an optimal, curated variety of films. Compare it to a museum: We don’t think of ourselves as owning any of the art, so we aren’t upset when it changes what’s on view from its collection. If you can reframe your perspective this way, my guess is that you will enjoy Netflix more.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A friend once chided me for laughing at my own joke. Is it wrong to laugh at your own jokes? After all, would I tell a joke that I didn’t think was funny?

—Norma

Jokes often hinge on a surprise ending, so laughing at a joke though you know the end seems to be a great endorsement for it (please send me the joke!). The only negative connotation I can imagine is that maybe your friend assumed the laughter was not genuine and you were trying to manipulate her into a higher level of enjoyment. In that case, you might want to look for a different friend.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Dog Droppings, Working Late, and Trying Out Girlfriends

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My partner and I live in a pretty 250-townhouse condo development, but we have a problem with people who don’t clean up after their dogs. Some are residents of our condo, but others are just passing through. Our condo fees pay someone big bucks to clean up after the dogs, and there’s a $50 fine when owners fail to clean up after their dogs. But you have to know who the dog owner is, catch him in the act, and report him to the condo corporation. This policy is not working. What can we do?

—Rachelle

We need to consider two forces in this situation: the positive force of social norms and the negative force of deterrence.

In terms of social norms, a great deal of research shows that what people do is less a function of what’s legal than of what they find socially acceptable. So if dog owners see a lot of droppings around the condo area, they will find it perfectly acceptable to continue in this tradition, but they would feel guilty leaving some doggy souvenirs behind if the grounds were pristine. So what is the lesson from social norms? For one, it means that violators are not only acting selfishly but are also making it more likely that others will follow. It also means that you should work extra hard to establish a better social norm—because once the social norm is set to clean up after the dogs, the good behavior will maintain itself.

In terms of deterrence, you can’t do much about outsiders, but I think you should try something more exotic with your condo neighbors. The way I see it, in the current “game” the dog owners try to hide the droppings, and the managers try to catch and punish the owners. I would try to alter the game so that it’s among the condo dog owners.

What if the condo management put money in a community fund to pay for a droppings-cleaner, as needed, and used whatever was left at the end of the month for a get-together for all dog owners and their dogs? If lots of money remained each month, the party would include food, drinks and doggy treats; if there was no money, it would just be water. This way, failing to clean up after the dogs would damage the community—the personal and social cost of these actions would increase—and people would be more careful.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My friend recently started working at a consultancy. We’d both heard about the brutally long working hours, but what surprised us was how people prized the number of hours they clocked, even when this went up to a ridiculous 16 hours a day. In this age when people are almost forced to have varied interests to define themselves, why would the consultants be shouting their boring lifestyles from the rooftops?

—Tushna

This kind of behavior might seem odd, but there are a few ways to reason about it. First, I suspect that in the world of consulting it is hard to estimate directly how good any particular individual is. If you worked in such a place, you would want your managers to know how good you are—but if they couldn’t directly see your quality, what would you do? Working many hours and telling everyone about it might be the best way to give your employer a sense of your commitment—which they might even confuse with your quality.

This is a general tendency. Every time we can’t evaluate the real thing we are interested in, we find something easy to evaluate and make an inference based on it. I often hear people complain, for example, about the cleanliness of airplane bathrooms. The reality is that we don’t really care about the bathrooms—what we should all care about is the functioning of the engines. But engines are hard to evaluate, so we focus on the bathrooms. Maybe people reason that if the airline is taking care of the bathrooms, it is probably taking care of the engines a well.

Another possibility: Your friend could be using the long working ours to keep score in some competition with his friends at work. This may not be the smartest contest, but people are highly motivated to win in almost every aspect of life—just look at the range of dares and ridiculous competitions on TV. From this perspective, maybe this is not the worst sort of competition for your friend to get into.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

In your last column you gave advice about the need to experience other people’s kids in order to decide if you should or should not have kids of your own. Does that advice hold for deciding if I should or should not marry my current girlfriend?

—Nick

In general, it is advisable to carry out experiments in a way that matches as much as possible the circumstances that you want to understand (in this case, how it would feel to be with this person for decades to come), so I would recommend spending two weeks with your girlfriend’s mother.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Saving money without thinking about it (is the best way to do it).

For many people, saving money isn’t just difficult; it’s a foreign concept. A recent study found that 58% of Americans do not have a formal retirement plan in place.¹ Why is even thinking about saving money so daunting to so many of us?

We spoke with Dan Ariely, professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He says that many people have difficulty saving their income because our minds and our environments are not naturally suited to thinking about money in the long term. In fact, our minds are not very good at thinking about the concept of money at all. To make it easier, he says, we need to change our environments in such a way that saving money happens automatically and we never even have to think about it.

[protected-iframe id=”22ca913879241a1f8836c2a9408ba6bf-1285065-1348005″ info=”http://dgjigvacl6ipj.cloudfront.net/media/swf/PBSPlayer.swf” width=”512″ height=”328″]

¹“According to Deloitte’s Retirement Survey, a majority of Americans — 58 percent — do not have a formal retirement savings and income plan in place.”

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like