A new online course for social entrepreneurs

At the Startup Lab (my incubator at Duke University’s Center for Advanced Hindsight), we aim to empower early stage startups to build better consumer health and finance products by teaching them how to apply both the findings and methods of behavioral economics to their products and business models.

While the in-depth Startup Lab program is limited to a small group of startups that go through our rigorous application process, it would be an injustice to not share some of its lessons with the greater community. So I’ve collaborated with +Acumen to create an online course to help social entrepreneurs make an impact – by designing products that change consumer behaviors for good. But what I am most excited about is the lesson on experimentation. I am always getting questions about how startups can experiment within their small companies (with few resources, especially time), and this course provides the tools for entrepreneurs to take a systematic approach to experimentation.

While the in-depth Startup Lab program is limited to a small group of startups that go through our rigorous application process, it would be an injustice to not share some of its lessons with the greater community. So I’ve collaborated with +Acumen to create an online course to help social entrepreneurs make an impact – by designing products that change consumer behaviors for good. But what I am most excited about is the lesson on experimentation. I am always getting questions about how startups can experiment within their small companies (with few resources, especially time), and this course provides the tools for entrepreneurs to take a systematic approach to experimentation.

Sign up for my Master Class with +Acumen on Changing Customer Behavior, now available here: http://bit.ly/2e11cOZ

Now Accepting Startup Lab Applications

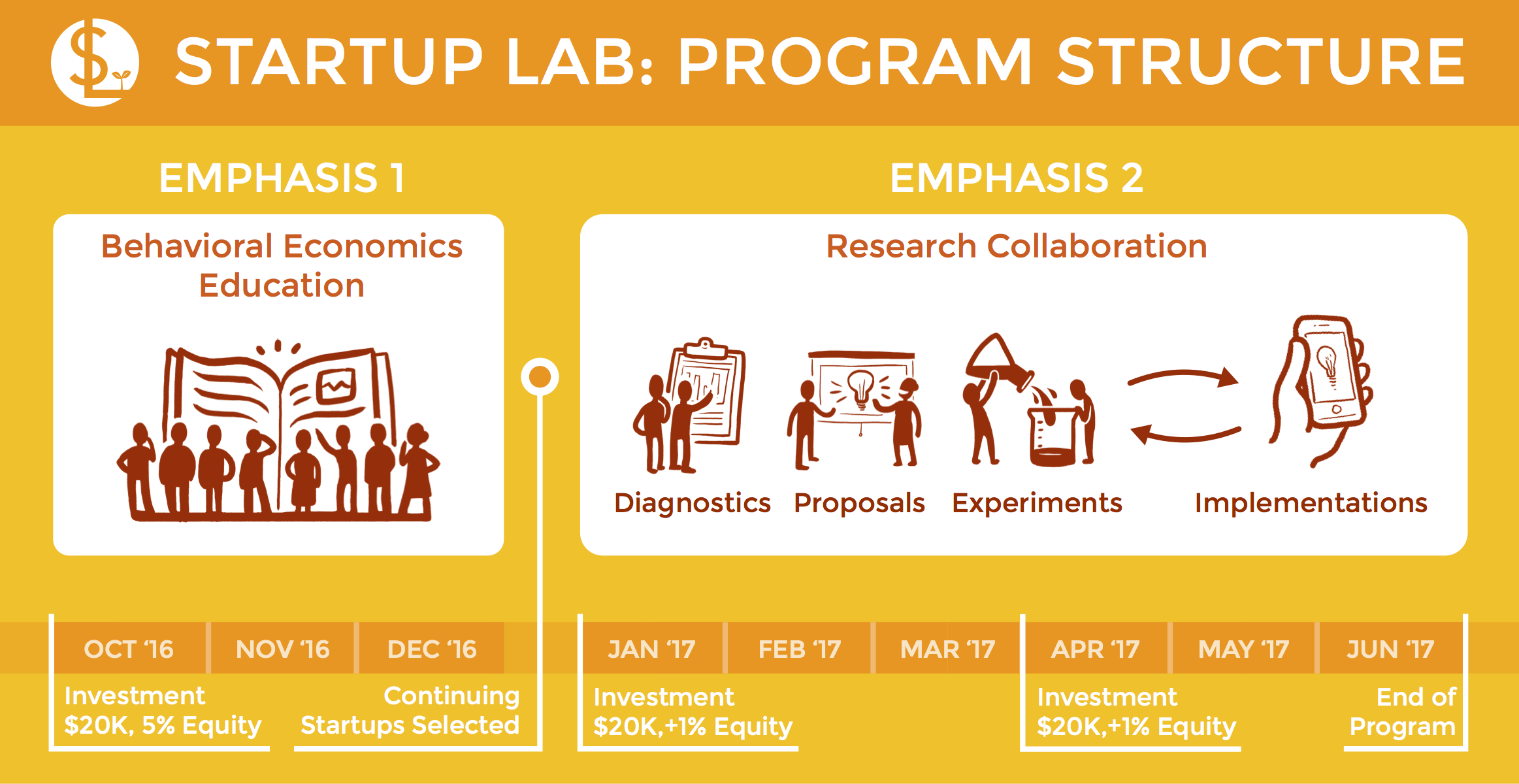

The Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke is now accepting applications for its second cohort of the Startup Lab, which begins October 2016.

The Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke is now accepting applications for its second cohort of the Startup Lab, which begins October 2016.

Health and Finance startups with a keen interest in applying behavioral insights to their products and exploring original research opportunities in collaboration with our world-class researchers are invited to apply.

We are looking for startup teams of 2-4 who are willing and able to be in Durham, NC for the duration of the program (October 2016-June 2017).

For details on the Startup Lab’s timeline, structure, and investment model, click here and check out the illustration below.

Strong applicants are health or finance startups committed to changing behavior for good. We are looking for teams who are passionate in their pursuit of well-researched solutions and validation through experimentation. We want to partner with teams who are intensely interested in learning more about behavioral economics and who see the implementation of behavioral insights into their product as being vital to their success.

Have we found each other? Apply for the Startup Lab here by Sunday, July 3, 2016 at 11pm EST.

A Summer internship at CAH

Just launched the Irrational Game

The day has finally come!

We’ve just launched the Irrational Game Kickstarter campaign, which means you can now get the game and some other rewards here.

The Irrational Game – We hope it will be a thought provoking, engaging and fun way to incorporate social sciences and human behavior into a challenging and strategic game.

It should also give you a way to reflect on your behavior and what you might want to change

If you consider supporting the project, please do it on the first day. A first day boost will give us great momentum for the entire campaign!

Thank you so much for all of your support. We can’t wait to get you the game.

Irrationally yours,

Dan

The 7 Irrational Behaviors of Black Friday

Every day of the year, American shoppers act irrationally. On Black Friday, however, shoppers’ irrationality and wildness climb to dangerously high levels. Why does Black Friday lead shoppers to grab and fight, especially when the stakes are often as low as fifty percent off toasters?

Over the last few decades, social scientists have cataloged the many different factors that lead to irrational consumer behavior, and Black Friday touches on nearly that entire list.

Luckily though, if shoppers stay aware of how Black Friday is designed to make them irrational—and if they take breaks, eat snacks, plan ahead, and keep a clear mind—then they can avoid falling victim to the “holiday.”

Here are seven reasons shoppers become so irrational and committed to deals on Black Friday, as well as a few ways you can protect yourself.

#1

Black Friday is like a hazing ritual

Black Friday shoppers are dedicated—they sacrifice sleep, football games, and significant others’ approval to make the early bird sales.

Black Friday shoppers are dedicated—they sacrifice sleep, football games, and significant others’ approval to make the early bird sales.

When people go through pain and effort to reach a goal, then the goal actually looks more attractive in an attempt to justify the unpleasant struggle. Effects like this are common—think of brutal college hazing rituals, where new members commit more intensely to the group rather than turn away.

A shopper’s first sleepless Black Friday is like a hazing ritual that makes the deals seem that much more attractive—they must be worth it after all that effort.

#2

Shoppers are too “depleted” to be rational

People are vulnerable to irrational tendencies all the time, but they are at their most vulnerable when they’re tired and overwhelmed. Behavioral scientists call this state “depletion.”

In a state of depletion, people just don’t have enough willpower to resist temptation or the cognitive faculties to make complex decisions. Even math whizzes and businesses majors will falter when depleted.

Black Friday shoppers arrive sleep-deprived and stressed from the holidays. For companies, Black Friday can seem like taking candy from a baby. Only here the baby resists even less.

#3

What’s another $10 after the first $500?

It hurts to spend money. There’s pain in parting with $10 for a flash stick. However, after spending $899 on a TV, the pain one feels parting with a Hamilton for a flash stick is practically gone.

It hurts to spend money. There’s pain in parting with $10 for a flash stick. However, after spending $899 on a TV, the pain one feels parting with a Hamilton for a flash stick is practically gone.

Restraint on Black Friday is even more unlikely because many shoppers tend to begin with the purchase of a large ticket item, like a TV or computer. After the big purchase, every $10 flash stick, $11 dollar t-shirt, or $13 kitchen knife, will not lead to the “pain of paying” that keeps people from buying every random thing on aisle during the other 364 days of the year.

Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky explain that people are initially “loss averse”: initially people really do not like losing money. However, once people start losing money, their aversion to losing money starts to go away. Accordingly, cautious spenders can quickly become big spenders.

#4

The shopping momentum phenomenon

Ever thought your friends turn into entirely different people when they go shopping? Well, scientific research suggests that indeed shopping does change people.

Ever thought your friends turn into entirely different people when they go shopping? Well, scientific research suggests that indeed shopping does change people.

Yale consumer researcher Ravi Dhar and colleagues find we are in a careful “deliberative” mind-set before purchasing an item—carefully weighing the pros and cons. Yet after the first purchase, a floodgate of “shopping momentum” opens up, and we make purchases more readily after.

Fortunately, the phenomenon of “shopping momentum” can be interrupted by a break in shopping. However, on frantic Black Friday breaks rarely occur, so shopping momentum is likely to persist for hours, if not the entire day.

#5

The Halo Effect — Amazing By Association

One problem for shopper rationality is that the amazing door buster deals on Black Friday may create a “Halo Effect” such that even the bad deals seem amazing by association.

One problem for shopper rationality is that the amazing door buster deals on Black Friday may create a “Halo Effect” such that even the bad deals seem amazing by association.

Black Friday shoppers are better off thinking of Black Friday as a day that has both good and some bad deals. Not every sale is a bargain.

#6

Black Friday requires math skills many consumers don’t have

To distinguish the good from the bad deals, it takes a little bit of math. But research shows many adult Americans lack the basic math skills necessary to evaluate the merits of a deal. For instance, many Americans don’t know that 10 percent of 1,000 is 100 or that 1/4 is larger than 3/20.

To distinguish the good from the bad deals, it takes a little bit of math. But research shows many adult Americans lack the basic math skills necessary to evaluate the merits of a deal. For instance, many Americans don’t know that 10 percent of 1,000 is 100 or that 1/4 is larger than 3/20.

Many Americans have what is known as “low numeracy” which means missing questions that national standards say elementary children should know. Are shoppers smarter than a 5th grader? Most often, the answer is no.

If shoppers don’t have the math skills, they are likely to get swept up in Black Friday. Shoppers without strong math skills should feel encouraged to bring along a friend who does, or even utilize smart phone applications that allow for better product evaluation.

#7

There’s no guilt when everybody’s doing it

Businesses want Black Friday to be crowded. Not just because they want lots of wallets, but because crowds change people. In the case of Black Friday, crowds can remove all sense of guilt.

Businesses want Black Friday to be crowded. Not just because they want lots of wallets, but because crowds change people. In the case of Black Friday, crowds can remove all sense of guilt.

Few shoppers feel guilty buying another half-off toaster when the customers next to them have flat screens in their carts. When everybody’s peers are doing it and some peers are “doing it worse,” the painful experience of parting with money becomes a joyous spending spree.

Indeed, research on “social influence” finds that the examples of others can drive people to irrational and even unethical behavior.

Final Reminders

Don’t get too tired. Use a calculator. Decide what you want ahead of time. And don’t get brainwashed. Yes, Black Friday is fun. Yes, Black Friday is a day of great deals. But Black Friday is also a trap that’s very easy to fall into. Happy and responsible shopping everyone!

By Troy Campbell

Originally posted last Black Friday.

The Power of Matching Donations

In a study conducted with Lalin Anik and Dan Ariely of Duke University, social norms were used to incentivize employees to give money to charity. Results were published in the paper Contingent Match Incentives Increase Donations.

In the study, the researchers told a set of contributors to a charitable giving website that their donations would be matched by the charity, but only if a certain percentage of contributors that day either 25, 50, 75, or 100 percent – “upgraded” to a recurring monthly donation. They found that the contributors in the “75 percent” condition contributed at a much higher rate than the other three groups, with as much as a 40 percent increase in committing to recurring donations.

Norton speculates that the higher number is due to a desire to conform to the social norms of other contributors – and not be the cause for the charity to deny matching funds. “No one wants to be the chump that spoils it for everyone else,” Norton says. In other research, that 70-75 percent threshold seems to be the point that has the biggest effect on on behavior – any higher and people may feel like the result is unattainable. The research also shows that the number doesn’t have to correspond to actual rates of participation. Just setting that goal institutes a standard that other people will strive to match.

To read more visit Forbes.com to read Michael Blanding’s article here.

The Seinfeld Rules of Lies

Seinfeld is one of the most popular American TV shows, created by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld. In one episode, George Costanza, the best friend of the main character, offered some advice about lying—some lies are not technically lies when taking into account the specific situation. Here is George’s list of 14 justified lies:

1. It’s not a lie if you believe it.

2. It’s not a lie if it doesn’t help you.

3. It’s not a lie if it hurts you.

4. It’s not a lie if it helps someone else.

5. It’s not a lie if it doesn’t hurt someone else.

6. It’s not a lie if everyone expects you to lie.

7. It’s not a lie if the other person knows the truth.

8. It’s not a lie if nobody can prove it.

9. It’s not a lie if you don’t get caught.

10. It’s not a lie if you don’t need to tell another lie to cover it up.

11. It’s not a lie if you were crossing your fingers.

12. It’s not a lie if you proceed to make it true.

13. It’s not a lie if nobody heard you say it.

14. It’s not a lie if nobody cares.

We were interested in whether people agreed with Costanza’s point of view. Do they justify these 14 behaviors? Do they believe lies are not technically lies if you don’t believe them, they don’t help you, and so on? To test these ideas, we made a short survey and released it through our “Sample Size Matters” App. Users indicated to what extent they agreed with each of George’s statements about lies on a scale of 1 to 7, 1 being strongly disagree and 7 strongly agree.

911 participants completed our survey, and, surprisingly, all of the statements were rated below a 4 (the mid-point of the scale), which means that people on average disagree with Costanza’s point of view. Additionally, the statements with the highest scores were “It is not a lie if you believe it” (mean=3.81) and “It is not a lie if you proceed it to make it true” (mean = 2.98).

Do these results suggest that people disagree with Costanza’s list of justified lies? Not necessarily. Our views about dishonesty may very well change depending on whether we’re the ones being dishonest—perhaps we believe these rules only when trying to justify our dishonesty.

Mazar, Amir and Ariely (2008) put forward a theory of dishonesty—individuals behave dishonestly enough to profit but honestly enough to maintain a sense of their own integrity. This is what they called the ‘self-concept maintenance theory’ and possibly explains Costanza’s rationalization.

At the end of our survey we asked participants to indicate what other situations they wouldn’t consider lying, and they came up with a lot of creative suggestions such as “It is not a lie if you miss the important details”, “It is not a lie if it is a joke or an irony”, “It is not a lie if it makes someone happy” and “It is not a lie if your salary or job depends on it.” Everyone could come up with at least one or two lies that are justified! Can you?

~Ximena Garcia Rada~

References

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of marketing research, 45(6), 633-644.

The Returns of Giving

When I moved to Durham for graduate school, I wanted to immediately start volunteering. As a student, I’m aware that time is a relentless constraint. Getting enough sleep, doing work, socializing, and having time to decompress are all priorities. So it’s hard not to feel overwhelmed and resistant to the idea of giving up more precious spare time to help others, even if the cause is important.

However, I knew that if I waited I would use my busy schedule as an excuse not to get involved. By pre-committing, I would be obligated to continue even as the semester became busier . I wanted to volunteer as a way to connect to my community and keep perspective that sometimes gets lost in the minutiae of research.

But what I didn’t realize was that I was inadvertently helping my future self feel less stressed when things got busy. Research finds that ironically, giving time to others actually can make us feel as though we have more of it ourselves.

This benefit of spending time on others seems counterintuitive. From a completely objective perspective, spending time on others reduces the minutes you have in a day—those don’t change. And indeed, we are actually less likely to take the time to help others if we’re short on time. However, if we do volunteer, our subjective perception of how much time we have can increase and affect our productivity and well-being.

Mogilner, Chance, and Norton (2012) found that giving time (volunteering or helping a friend) was more effective in increasing perceptions of future time than were wasting time, spending time on oneself, or unexpected free time. Moreover, they found that those who gave their time were more likely to commit more time and follow through on additional surveys. The mediator of this effect was self-efficacy. People feel more capable after taking the time to help others. Spending time on others may implicitly signal extra time, but also increased self-efficacy may make us feel that we can accomplish more with our time, effectively expanding it.

Sometimes, how much time we feel we have is actually more important than how much time we actually have. Because within a range, our feelings about time affect our happiness, stress levels, and productivity more than the actual number of hours.

Does this mean we shouldn’t indulge in TV, Facebook, or relaxing with friends? Of course not—the benefits of giving time aren’t infinite. Given the objective constraints, giving too much time will increase stress and won’t make use feel like we have more time.

Nevertheless, this discrepancy between how we expect volunteering to affect our sense of time, and how it actually does, is important for better budgeting our time. I have noticed that when I get home after volunteering, I immediately respond to all the emails that have been piling up, focus better on my work projects, and feel more accomplished by the end of the night. Despite having less time, I tend to use it more effectively.

Indeed, this mismatch between prediction and results applies to budgeting money as well: although people predict that they will be happier spending money on themselves, they actually feel better and wealthier spending on others.

When we are feeling the constraints of money, time or something else, we may actually help ourselves by giving to others. Moreover, for those who care less about the fuzzy concept of well-being, there are hints in the research suggesting that not only does giving to others affect our outlook, but it also might actually make us more efficient and productive.

~Dianna Amasino~

Last Night's Dishonesty Debate

Last night, legendary philosopher Peter Singer, distinguished psychologist Paul Bloom, and our very own expert behavioral economist Dan Ariely had a cross-Coursera “debate” on the ins and outs of dishonesty, morality, and ethics. Watch the fun and insightful discussion below, and skim the highlights on our twitter account or under the hashtag #dishonestydebate!

Studies across cultures: A useful guide.

Cross-cultural research is becoming increasingly popular, but many researchers are failing to understand the unique challenges it poses. Cross cultural psychology explores how culture influences behavior and attitudes, and cultural psychologists aim to study subjects from two or more cultures using equivalent methods of measurements (Triandis & Brislin, 1984).

This research can often be difficult to conduct, and as someone in the midst of working through these problems in our lab, I’ve noticed some of these difficulties. I’m sharing what I’ve learned here as a quick guide to both help other researchers design better studies and help readers know enough background to better evaluate this research.

Five Challenges of Cross Cultural Research

1. Design:

The research question and design should be very clear before embarking on cross-cultural research. And when I say clear, I mean crystal clear. What are the specific hypotheses? What analysis will you run? Do you have variables that will allow you to run those tests? Do you have proper controls?

Always start with a pilot study with at least one of the target cultures (or a population in your home country), because it’s surprising how many things sometimes just don’t work. For instance, when conducting survey research, it’s important to test your constructs, such as sub-scales. If you’re going to spend thousands of dollars and months working on a project, make sure your scales work with your population, and don’t just assume it’ll work based on past research.

2. Translations:

How can you express the exact same idea in several languages? Or in the same language but to different cultural populations, such as British vs. American, or urban vs. rural? Again, pilot testing is key. Don’t just show it to a few research assistants who speak the language, get it out to the people that you’ll be studying.

How should you actually translate? We recommend the forward-backward method, where the translated document is translated back to the original language for comparison.

3. Consistency:

As a cross-cultural researcher, you must standardize processes, settings, and other factors of your research so that the only difference between your samples is their culture. Prepare documents like protocols and scripts for experimenters, and go over them again and again. Different cultures have different customs and social behaviors, and those social behaviors, even if they’re as small as how to administer a survey in a coffee shop, cannot vary across studies without jeopardizing the data. This is problematic when you have just one culture, one survey, and one research assistant. When you have ten cultures, one survey in different languages, and many research assistants across the globe, things can get very messy, fast. Remember though, if things are messy, then it’s important to be honest about it in the write up. In the modern age of ‘imperfect’ data, reviewers are looking for and respectful of honesty.

4. Cultural Customs:

Try to have a local person or team who is willing to be involved in the implementation of the project; they will contribute greatly with local advice and organization.

There will be many local factors that you won’t be aware of if you’re not familiar with the culture. For example, you may not know where to collect data, how to deal with local businesses while asking permission, or even how to approach subjects in a nice and professional way. Things like these may vary across countries, and locals are the only ones who can fill you in. It’s also important to understand all these differences before collecting data. For instance, a methodology might work well in one cultural but, because of social norms, not in another. Again, pilot test and know as much as you can ahead of time.

5. Paying Participants:

Does your study involve paying participants? If so, make sure to adjust that payment considering the cost of living of each country. Remember $1 in the USA is not the same as $1 in other countries, so you must make payments equivalent! We recommend indexes like the Purchasing Power Parity Index (World Bank) or the Big Mac Index (The Economist). Also consider whether your samples are used to being paid to do experiments and if your payment varies from this normal payment model.

In the end, the most important thing to remember with cross-cultural psychology is to plan ahead. When evaluating cross-cultural research in journals or news articles, the critical reader should consider what factors the researchers might have overlooked.

One final consideration is to remember that all research is only part of the puzzle. There is no definitive cross-cultural psychological paper, and there never will be. So it’s important to keep each finding in perspective.

~Ximena Garcia-Rada~

Further readings about cross-cultural psychology:

– Keith, K. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Contemporary Themes and Perspectives.

– Shiraev, E. B. & Levy, D. A. (2010). Cross-cultural psychology: critical thinking and contemporary applications (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson/Allyn Bacon.

– Triandis, H. C., & Brislin, R. W. (1984). Cross-cultural psychology. American Psychologist, 39(9), 1006-1016. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.39.9.1006

– Hofstede, G., Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like