My Take on the NY Times Pay Wall

A few weeks ago, the New York Times announced that they would start charging readers for online content in early 2011, and since then the million-dollar question has been: will it work? Will readers fork over the cash to keep reading the Times, or will they go elsewhere?

The main problem of this approach is that over the years of free access, the New York Times has trained its readers for years that the right price (or the Anchor) is $0 – and since this is the starting point it is very hard to change it.

So, should the New York Times give up? The trick with anchoring is that although we are not willing to pay more for the same thing, we are willing to pay more for different things. What this means is that one approach that the New York Times could take is to present us with a new experience so that we don’t associate it with the previous anchor, and are open to new pricing.

Let me explain. Because we’re not very good at figuring out what we are willing to pay for different products and services, the initial prices that new products are presented with can have a long term effect on how much we are willing to pay for them. We basically can’t figure out how much pleasure the New York Times gives us in terms of $ — so we go back and pay the same price we have paid before. This means that getting people to pay for something that was free for a long time will be very challenging, but it also means that if the New York Times were to offer some new service at the same time that they start charging, they might be more likely to pull it off.

It’s a strategy that Starbucks founder Howard Shultz put to good effect. Before he came along, consumers were used to paying much less for coffee from spots like Dunkin’ Donuts. So to incite us to shell out more for his coffee, he worked hard to separate Starbucks from other coffee shops. He designed it to feel like a continental coffeehouse, putting in showcases with croissants, displaying french presses, and coming up with exotic drink and size names. He redefined the coffee experience, and by doing so, convinced us to pay more.

The Times could try to take on a similar approach …

Irrationally Yours,

Dan

The Internet and Self-Control: An App To the Rescue

I have “a friend” who will head over to a coffee shop to get work done. Not because she’s unable to work at her desk or because she needs the presence of other people, but rather because it lets her get away from the Internet and all its distractions.

True, she could easily stay put by just keeping her browser closed. But that requires self-control, and as we all know, keeping ourselves in check is easier said than done. Whatever the resolution (start dieting, start saving, stop procrastinating, etc.) we routinely stick to it for a bit and then cave. We make the resolution in one state of mind – a cool, rational state – and then break it when temptation strikes.

That’s the reason for my friend’s coffeeshop strategy: precommitments allow us to commit upfront to our preferred course of action. In her cool, rational state, my friend can decide not to surf the web and make a point to leave the wireless behind; later, when temptation strikes, she’ll be out of luck. Access denied.

On the whole, I like my friend’s strategy. But there’s a potential problem: what if she needs the Internet to do her work? What then?

Not to worry – there’s an app to the rescue: SelfControl, a free Mac-only software program that blocks access to incoming/outgoing mail servers and websites and was thought up by artist Steve Lambert. (As the son of an ex-monk and an ex-nun, he’s well-versed in self-control.) The app only takes seconds to install and comes with all the flexibility that my friend’s coffeeshop strategy lacks.

Instead of taking leave of the Internet all-together, you can pick and choose what you can and can’t access, and for how long. If Facebook is your particular time-suck, then add its URL to SelfControl’s blacklist and the program will block Facebook and nothing else. If Twitter is another danger zone, then by all means, throw its URL into the mix. Next, figure out how long you want to block them for – anywhere from one minute to twelve hours – and move the slider accordingly. Then press start and you’re good to go.

But here’s the key part: once you click start, there’s no going back. (No wonder the app has a skull and crossbones symbol as its icon.) Switching browsers won’t help you, and neither will restarting your computer or even deleting the app. You won’t get those websites back until the timer runs out. As such, it’s as effective of a precommitment as seeking out a wireless-free zone.

Though temptation routinely deflects us from our long-term goals, our struggle with self-control isn’t a lost cause. Once we realize and admit our weakness, we can do something about it by taking on clever precommitments that save us from ourselves. In an ideal world we wouldn’t need the SelfControl app, but in this world it sure is useful.

Irrationally Yours,

Dan

P.S. For more on precommitments, check out this post on self-control and sex.

A short story

A few months ago I posted four short stories that undergraduate students in my class wrote.

In response to these stories, some readers proposed their own short stories, and today I am posting the fist of these:

Spending money

We have lots of discussions about how to get people to save more, which is clearly important.

But today I want to ask a question about spending money: Assume you had $20,000 to spend (and that you could not save it), what would be the ideal way to spend it? In other words, what would be the way to spend this sum if your goal was to get the most joy and happiness out of this amount?

I am not asking because I have an answer, or even an idea of how to do research on this — I am asking because I really don’t know.

So — any input will be welcomed…

Irrationally yours

Dan

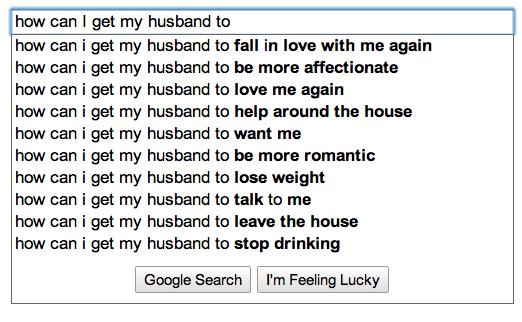

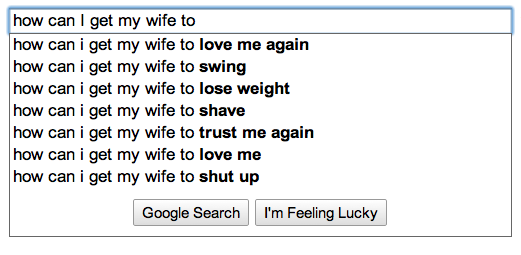

What Husbands and Wives Search for on Google

A few days ago we looked at some telling search suggestions by Google when it came to what boyfriends and girlfriends searched for in their relationships. On the heels of this insight, I wanted to see what changes when we get older and get married…:

What we find, both sides seem to care more about love, but in general the it seems that not much has changed since the days of dating for married couples. According to Google, these gender differences that we found earlier tend to persist…

What we find, both sides seem to care more about love, but in general the it seems that not much has changed since the days of dating for married couples. According to Google, these gender differences that we found earlier tend to persist…

For a very elegant tool that lets you play with such searches, see: http://hint.fm/seer/

Attention Predictably Irrational Fashionistas!

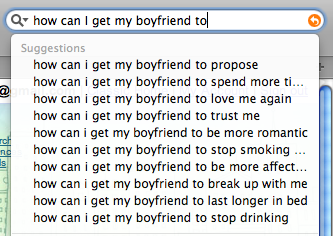

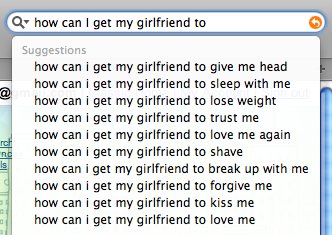

What boyfriends and girlfriends search for on Google

You know how Google sometimes “predicts” what you might be searching for by giving you a little drop down menu of suggested search queries? These suggestions, of course, are based on what other users frequently search. So I tried teasing out some gender differences. Look at the pictures below.

This shows Google’s remarkable power as a source of data on a range of human behaviors, emotions, and opinions. It gives us insights into what people might care the most about concerning a given topic. When people search a particular political leader, what are their main concerns? What are people secretly guilty about? For better or for worse, Google’s obsession with collecting and refining data has given us a window into each other’s fascinating and telling curiosities.

The Science Behind Exercise Footwear

A few weeks ago Reebok unveiled a walking shoe purported to tone muscles to a greater extent than your average sneaker. All you had to do was slip on a pair of EasyTone and the rest would take care of itself.

Exercise without exercise? Great!

Considering the abracadabra-like quality of the shoe, it’s no surprise that it’s been selling like hotcakes. The question of course is “ does it work”?

According to a recent New York Times article on the topic, Reebok has accumulated “15,000 hours’ worth of wear-test data from shoe users who say they notice the difference.” (The company also quotes a study as support, but it’s one they commissioned themselves and only carries a sample size of five.) The two women quoted in the article further echo this sentiment.

Reebok’s head of advanced innovation (and EasyTone mastermind), Bill McInnis, says the shoe works because it offers the kind of imbalance that you get with stability balls at the gym. Unlike other sneakers, which are made flat with comfort in mind, the EasyTone is purposely outfitted with air-filled toe-and-heal “balance pods” in order to simulate the muscle engagement required to walk through sand. With every step, air shifts from one pod to the other, causing the person’s foot to sink and forcing their leg and backside muscles into a workout.

But as the Times article proposes at the end (without explicitly using the term), the shoe’s success could instead come from the placebo effect. Thanks to Reebok’s marketing efforts, buyers pick up the shoes already convinced of their success, a mind frame that may then cause them to walk faster or harder or longer, thereby producing the expected workout – just not for the expected reason.

And there are some reasons to suspect this kind of placebo effect: In a paper by Alia Crum and Ellen Langer. Titled “Mind-Set Matters: Exercise and the Placebo Effect.” In their research they told some maids working in hotels that the work they do (cleaning hotel rooms) is good exercise and satisfies the Surgeon General’s recommendations for an active lifestyle. Other maids were not given this information. 4 weeks later, the informed group perceived themselves to be getting significantly more exercise than before, their weight was lower and they even showed a decrease in blood pressure, body fat, waist-to-hip ratio, and body mass index.

So, maybe exercise affects health are part placebo?

Irrationally Yours

Dan

P.S. If you’ve had the opportunity to try the shoe, leave a comment and let us know what you thought.

The Significant Objects Project

Would you pay $76 for a shot glass? What about $52 for an oven mitt? And $50 for a jar of marbles?

You may shake your head and say no way, but in a recent series of eBay auctions, the consumers did just that: they shelled out considerable cash for objects that to all appearances should never have fetched more than a couple bucks.

So what made the difference? Each item came with a unique tale.

The auctions were part of the Significant Objects Project, an experiment designed to test the hypothesis that “narrative transforms the insignificant into the significant.” Or, put differently, the goal was to determine whether you could take an object worth very little and make it worth much more by giving it a story, by endowing it with meaning.

To that end, the project’s originators – NY Times columnist Rob Walker and author Josh Glenn – bought up 100 unremarkable garage sale knickknacks for no more than a few dollars each, and then had volunteer writers whip up fictional back stories for them. This, they thought, would up the trinkets’ objective value.

They were right. Whereas the objects had cost Walker and Glenn a total of $128.74 to buy, the same trinkets netted a whopping $3,612.51 on eBay when paired with stories. This Russian figurine, for example, came with the original price tag of $3 but sold for $193.50. And this kitschy toy horse made the leap from $1 to $104.50. (See also:$76 shot glass, $52 oven mitt, $50 jar of marbles)

The results may seem surprising, but this is actually something we see all the time. It’s the basic idea behind the endowment effect, the theory that once we own something, its value increases in our eyes. (In one study, Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler (1990) randomly divvyed up participants into mug owners and buyers, and found that whereas owners requested around $7 for their mugs, the buyers would only pay an average of $3.)

But ownership isn’t the only way to endow an object or service with meaning. You can also create value by investing time and effort into something (hence why we cherish those scraggly scarves we knit ourselves) or by knowing that someone else has (gifts fall under this category).

And then there’s the power of stories: spend a fantastic weekend somewhere, and no matter what you bring back – whether it’s an upper-case souvenir or a shell off the beach – you’ll value it immensely, simply because of its associations. This explains the findings of the Significant Objects Project, and also how other things like branding works

Irrationally yours

Dan

The Psychology of Gift-Giving

Here it is again: holiday gift-giving season – the best win-win of the year for some, and a time to regret having so many relatives for others.

Whatever your gift philosophy, you may be thinking that you would be happier if you could just spend the money on yourself – but according to a three-part study by Elizabeth Dunn, Lara Aknin, and Michael Norton, givers can get more happiness than people who spend the money on themselves.

Liz, Lara and Mike approached the study from the perspective that happiness is less dependent on stable circumstances (income) and more on the day-to-day activities in which a person chooses to engage (gift-giving vs. personal purchases).

To that end, they surveyed a representative sample of 632 Americans on their spending choices and happiness levels and found that while the amount of personal spending (bills included) was unrelated to reported happiness, prosocial spending was associated with significantly higher happiness.

Next, they took a longitudinal approach to the topic: they gave out work bonuses to employees at a company and later checked who was happier – those who spent the money on themselves, or those who put it toward gifts or charity. Again they found that prosocial spending was the only significant predictor of happiness.

But because correlation doesn’t imply causation, they next took one more, experimental, look at the topic. Here, they randomly assigned participants to “you must spend the money on other people” and “spend the money on yourself” conditions — and gave them either $5 or $20 to spend by the day’s end. They then had participants rate their happiness levels both before and just after the experiment.

The results here were once more in favor of prosocial spending: though the amount of money ($5 vs $20) played no significant role on happiness, the type of spending did.

Surprised by the outcome? You’re not the only one: the researchers later asked other participants to predict the results and learned that 63% of them mistakenly thought that personal spending would bring more job than prosocial purchases.

Happy holidays

Dan

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like