Why you should watch football until the very end

By Wendy De La Rosa, Dan Ariely, and Kristen Berman

During the last month, the World Cup has captivated the globe, including our team at Irrational Labs. We have watched all 64 games and rejoiced / suffered through each of the 171 goals (not counting penalty kicks). This 2014 FIFA World Cup turned out to be an entrancing tournament: Eight of the “Round of 16” matches went into overtime, four went to penalty kicks, and the final match ended with Germany scoring in the 113th minute!

When we watched the now infamous Germany – Brazil game, we couldn’t help but come up with some interesting behavioral questions. When German midfielder Thomas Mueller scored the first goal against Brazil 11 minutes into the game, many of our Brazilian friends said this is just the start of the game.

And while we all know what happened, we started thinking: Were our Brazilian friends onto something – are there more or less goals and attempts late in the game?

One would stipulate that there is no difference in scoring between the first and the second half. Every goal matters equally, regardless of when it is scored, and players should attempt to score with the same amount of effort and success over time.

Another hypothesis is that fewer goals are scored in the second half as players fatigue Unlike basketball, where players are often substituted in and out, most of the football players are on the field for the full 90 minutes of play (sometimes 120 minutes if it goes to overtime).

Yet another hypothesis is that players score more goals in the second half as they are closer to the end of the game. Motivation research suggests that agents are more motivated as they near the end of their stated objective, whether a marathon or a life altering championship.

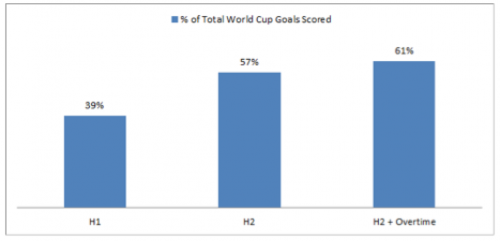

It turns out our Brazilian friends were right; more goals are scored in the second half! Of the 171 goals scored in the World Cup, 39% of the goals were scored in the first half, 57% in the second half, and 61% in the second half when we include overtime.

After learning that players score more goals in the second half, we wanted to know why. There are two ways to increase goals scored: increase attempts or increase skill (measured as goals / attempts). Which one is at play here?

The skill hypothesis stipulates that players are “super humans” who perform best when they are under pressure. Consider German Mario Gotza, a substitute midfielder, scoring the game winning goal against Argentina just seven minutes before the end of the match.

To answer this question, we compared a team’s skill in the entire game to a team’s skill in the last 15 minutes of a game. Our analysis showed that there is no statistical difference in skill when you compare these 15 minutes. This is consistent with an interesting study done by Dan Ariely and Racheli Barkan, where they studied the shooting percentages of “clutch players.” Clutch players are NBA players who are widely regarded as “basketball heroes who sink a basket just as the buzzer sounds.” As it turns out, clutch players do not become better basketball players as the pressure increases in the last few minutes of critical games. Basketball players, like our football players, do not increase in skill towards the end of the game.

So if it’s not a question of increased skill (% conversion), it must be a question of effort (number of attempts). Given this finding, we decided to analyze the number of attempts made by players, and whether they increase as the game wears on. Which team is attempting the most goals at the end of the game? One hypothesis is that the leading team increases their attempts as they are more confident and have strong momentum behind them. The other hypothesis is that the trailing team would attempt more goals at the end of the game because the cost of losing is more salient to them.

We can see loss aversion playing out in golf green. According to researchers, Devin Pope and Maurice Schweitzer, “Golf provides a natural setting to test for loss aversion because golfers are rewarded for the total number of strokes they take during a tournament, yet each individual hole has a salient reference point: par (the typical number of shots professional golfers take to complete a hole).” After analyzing PGA Tour putts (the last shot before a hole), they noticed that golfers are extremely loss averse. Golfers make putts for birdie (one shot less than par) significantly less often than identical-length putts for par (getting to par). The researchers estimate that this loss aversion costs the average pro golfer about one stroke per 72-hole tournament, and the top 20 golfers about $1.2 million in prize money a year.

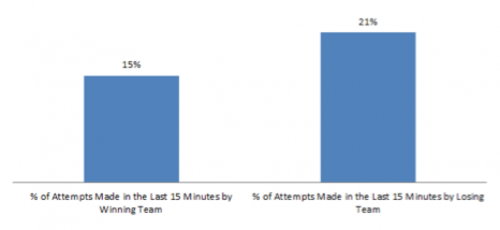

Does this theory hold true in football? After analyzing the data, we found that during the last 15 minutes of each game, number of attempts made by the trailing team (as a percentage of their total attempts made during the game) increase, while the number of attempts made by the winning team decreases.

Why is this? We believe we can explain this phenomenon with loss aversion. Loss aversion is the behavioral economic concept that states that we value losses more than we value commensurate gains. The other stipulation in loss aversion theory states that we are risk seeking in losses and risk averse in gains. In other words, our risk appetite increases when we are losing. This phenomenon is known as “risk shift.”

The feeling of loss aversion is heightened in football. Think about the cost of a goal in football compared to the cost of a basket in basketball. Because goals are so difficult to make, the cost of giving up a goal is greater than the cost of not making a goal. Thus, teams are naturally more defensive, focused on avoiding “a goal” or a “loss” much less than “scoring” or “gaining” for most of the game.

Loss aversion is a powerful concept, and we are all susceptible; even world class football players. So to go back to our Brazilian fans, expecting more effort as the game continues is a reasonable expectation. Unfortunately, and as the Brazilian fans found out, sometimes effort is not enough.

Ask Ariely: On the Perks of Pickup Lines, Puppy Problems, and Probing Personality

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am happily married and was never much for the bar scene. But I do wonder if those cheesy pickup lines actually work—”If I told you that you had a beautiful body, would you hold it against me” and so on. I can’t imagine anyone would buy such transparently empty flattery, but these lines are so common that they must be doing something. Any insight?

—Barbara

I’m no expert here, but my guess is that these kinds of pickup lines work much better than you might expect. Some interesting research shows that we love getting compliments, that we are better disposed toward people who give us compliments and that we like those people even when we know that the compliments are insincere. So beyond the pickup lines, the real question is why we don’t give compliments more frequently. After all, they’re free, and they make the recipient happy. Try out some pickup lines and compliments on your husband for the next few weeks, and let me know how it works out.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

One of the not very well-paid cleaners working in my office sometimes chats with me about her life, including her family’s financial difficulties. Last week, she told me that she had just got a puppy. I was shocked that she would take on the responsibility of caring for a pet when she doesn’t have the money to take care of her family. How could someone in her situation be so careless and irresponsible with money?

—Andrea

This probably wasn’t a great choice on her part, but to understand how she could make such a decision—and to figure out if you or I would have made the same call if we were in her shoes—we need to better understand her circumstances and capacity to make good choices.

Consider the following scenario: You are relatively poor, and as you go through your day, every decision you make is consequential. You decide whether to get coffee and walk to work, or skip the coffee and take the bus. You decide whether to take a short break or make another $6. On your way home, you decide whether to fill a prescription or to have a better dinner. When you get home, you are exhausted from all the difficult choices you’ve made throughout the day. You are depleted—the term we use to describe the type of mental exhaustion that stems from making decisions and resisting temptation. And now your children ask you for the 100th time to get a puppy. You know that, for your long-term financial well-being, you should resist. But do you have the mental stamina? Unlikely.

You may be more likely to make better decisions than your colleague, but we don’t know whether that is because you are better at making sensible long-term decisions—or because you simply aren’t as depleted at the end of the day. My guess is that life circumstances and depletion, not heedless irresponsibility, explain many such less-than-desirable decisions.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A few years ago, I discovered the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and decided to take the test, which seemed pretty detailed. When I was shown my resulting “personality type,” I was blown away: It seemed to explain things about my personality that I had felt but had never put into words. But ever since, I’ve been insecure about whether my MBTI type is my “true type” or just confirmation bias. Help, please?

—Cory

Next time, just look at the horoscope. It is just as valid and takes less time.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Sports and Loss Aversion

I got this question about the World Cup and I can’t put it in my WSJ column, but I still think it is worth while answering, and particularly today.

Dear Dan,

You have mentioned many times the principle of loss aversion, where the pain of losing is much higher than the joy of winning. The recent world cup was most likely the largest spectator event in the history of the world, and fans from across the globe were clearly very involved in who would win. If indeed, as suggested by loss aversion, people suffer from losing more than they enjoy winning — why would anyone become a fan of a team? After all, as fans they have about equal chance of losing (which you claim is very painful) and for winning (which you claim does not provide the same extreme emotional impact) – so in total across many game the outcome is not a good deal. Am I missing something in my application of loss aversion? Is loss aversion not relevant to sports?

Fernando

Your description of the problem implies that people have a choice in the matter, and that they carefully consider the benefits vs the costs of becoming a fan of a particular team. Personally, I suspect that the choice of what team to root for is closer to religious convictions than to rational choice — which means that people don’t really make an active choice of what team to root for (at least not a deliberate informed one), and that they are “given” their team-affiliation by their surroundings, family and friends.

Another assumption that is implied in your question is that when people approach the choice of a team, that they consider the possible negative effects of losing relative to the emotional boost of winning. The problem with this part of your argument is that predicting our emotional reactions to losses is something we are not very good at, which means that we are not very likely to accurately take into account the full effect of loss aversion when we make choices.

In your question you also raised the possibility that loss aversion might not apply to sporting events. This is a very interesting possibility, and I would like to speculate why you are (partially) correct. Sporting events are not just about the outcome, and if anything, they are more about the ways in which we experience the games as they unfold over time (yes, even the 7-1 Germany vs Brazil game). Unlike monetary gambles, games take some time, and the time of the game itself is arguably what provide the largest part of the enjoyment. To illustrate this consider two individuals N (Not-caring) and F (Fan). What loss aversion implies is that N will end up with a neutral feeling with any outcome of the game, while F has about equal chance of being somewhat happy or very upset (and the expected value of these two potential outcomes is negative). But, this part of the analysis is taking into account only the outcome of the game. What about the enjoyment during the game itself? Here N is not going to get much emotional value watching the game (by definition he doesn’t care much, and he might even check his phone during the game or flip channels). F on the other hand is going to experience a lot of ups and downs and be emotionally engrossed and invested throughout the game. Now, if we take both the process of the game and the final outcome into account — we could argue that the serious fans are risking a large and painful disappointment at the end of each game, but that they are doing it for the benefit of extracting more enjoyment from the game itself — and this is likely to be a very wise tradeoff that maximizes their overall well-being.

This analysis by the way has another interesting implication — it suggests that the value of being die hard fans is higher for games that take more time, where the fans get to enjoy the process for longer. Maybe this is why so many sports take breaks for time outs and advertisements breaks — they are not only doing it to increase their revenues, but they are also trying to give us, the fans, more time to enjoy the whole experience.

Ask Ariely: On Misplaced Cars and Memory, Forgotten Loans, and The Mystery of Marriage

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A few days ago I got out of a meeting and couldn’t find my car keys. I suddenly realized that I must have left the keys in the ignition. I forgetfully do that from time to time, and my husband scolds me for it. Frantic, I headed for the parking garage, only to discover that the car was gone. I immediately called the police. I later called my husband and told him, “I left the keys in the car, and it’s been stolen.” There was a moment of silence. He said, “Are you kidding me? I dropped you off!” Embarrassed, I said, “Can you come and get me?” And his response was, “I’ll be there as soon as I convince this cop that I didn’t steal your car.”

Should I expect more moments like this as I start to pass into my golden years? Any advice on how to make it less painful?

—Pat

Memory is a gift that we don’t sufficiently appreciate until we start losing it. But appreciating memory isn’t helpful in figuring out what you can do to decrease memory loss.

The best tools are habit and repeated behavior. You may no longer be able to remember easily where you left your glasses or book the last time you used them, but if you always try to put them in the same place, the odds are higher that you will find them. Rehearsal is also useful: Repeating things multiple times helps to transfer them from short-term to long-term memory (with the risk of looking crazy if people see you talking to yourself). Another tool is to take notes that will bypass the need to rely on memory (aside from remembering to look at your note pad). A modern version of such notes is to use your phone to take pictures, which come with even more context around the item you are trying to remember.

Your story is highly amusing, so perhaps you can also try to see the funny side of these senior moments. In fact, if you can make a point of sharing them with your friends and family, you will benefit from remembering those happy moments, too.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Many years ago a friend of mine asked me to lend her a substantial amount of money. At the time I was happy to help her, but now it has been years since I lent her the money. She has never mentioned it, and the shadow of this exchange is clouding our relationship. What should I do? Should I say something?

—Mariel

Because you’re the one who loaned the money, you probably think that she ought to be the one to bring up the topic. The problem is that the asymmetry in your relationship makes it much, much harder for her to do this. Someone unquestionably should, though, and given the power dynamic I think it should be you. It might be a bit uncomfortable in the short run, but in the long run, it could save your friendship.

Next, the question is what to say. If you need the money, I would say something like, “A few years ago I was happy to loan you some money, but I’m trying to sort out my accounts in the next few weeks. I just need to know when would be a good time for you to repay me.” If you don’t need the money and are willing to give it to your friend, I would say something like, “A few years ago, you asked me for some money, and I just wanted to make sure that you knew I always meant it as a gift.”

Either way, the topic would be out, and you would have a better chance to resume your friendship.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why is the divorce rate so high?

—Jacob

It is hard to imagine we can be happy with any decision even a year down the line, much less 10, 20 or even 50 years later. Frankly, I am amazed by how low the divorce rate is.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Sticking to Stocks, Stopping the Struggle, and Stifling Smoking

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

How can we get people to follow their long-term strategies when investing in the stock market? Many of my clients say they’re willing to take risks, but when the market goes down, they change their minds and ask me to sell. How do I get my clients to stick to their game plans and not break their own rules?

—Ganapathy

I suspect that you are asking about is the so-called “hot-cold-empathy gap,” where we tell ourselves something like, “I can handle a level of risk where I might get gains of up to 15% and losses of up to 10%.” But then we lose 5% of our portfolio, panic and want to sell everything. In such cases, we usually think that the cooler voice in our head (the one that set the initial risk level and portfolio choice) is the correct one, and we think that the voice that panics at short-term markets fluctuations is the one causing us to stray.

From this perspective, we can think about two types of solutions. The first option is to get the “cold” side of ourselves to set up our investments in ways that are hard for our “hot,” emotional selves to undo in the heat of the moment. For example, we could ask our financial advisers not to let us make any changes unless we’ve slept on them for 72 hours. Or imagine what would happen if our brokerage accounts had a built-in penalty every time we tried to sell right after a market dip. Such approaches recognize that our emotions flare up and make it harder for us to act on them.

A second option: You could try not to awaken your emotional self, perhaps by not looking at our portfolio very often or by asking your significant other (or financial adviser) to alert you only if your portfolio has lost more than the amount you’d indicated that you were willing to lose.

Either way, the freedom to do whatever we want and change our minds at any point can be the shortest path to bad decisions. While limiting our freedom goes against our democratic ideology and faith in human nature, such tactics are sometimes the best ways to guarantee that we stay on the long-term path.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My boyfriend and I keep having terrible fights, with lots of verbal and emotional abuse on both sides. After each of these fights, we really hate each other. But a few days later, we become loving again—until we have another awful blowup after a few more days. I keep hoping that things will change and that these fights will stop. Am I being naive, or can people change?

—Amy

I’m sorry — this sounds very painful. You may be experiencing the ostrich effect: burying your head in the sand despite the accumulating evidence. Of course, this is hardly unique to your difficult situation. We all sometimes overestimate very small probabilities — hoping against hope that the real nature of the world (and people close to us) will be different from what we’re experiencing.

It is not easy to overcome the ostrich effect, but here’s one approach: Distance yourself from the situation and try to take “the outside view” — the perspective of someone not personally involved in this problem. For example, imagine that someone else was having this exact problem and described it to you in great detail. What advice would you give them? What if the person was someone close to you, like your sister or daughter?

Take the outside view, make a recommendation to this other person—and then follow your own advice. And good luck.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What’s the best way to get people to stop smoking?

—Myron

The problem with smoking is that its effects are cumulative and delayed, so we don’t feel the danger. Imagine what would happen if we forced cigarette companies to install a small explosive device in one out of every million cigarettes—not big enough to kill anyone but powerful enough to create a bit of damage. My guess is that this would stop smoking. And if we can’t implement this approach, maybe we can get people to start thinking about smoking this way.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Anticipating Adventure, Watching it Work, and Overpriced M&Ms

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

For my birthday, my boyfriend gave me a rather expensive coupon for tandem sky diving. I could have used the coupon that weekend, when the sky diving season ended, but I chose instead to wait a few months for the new season to begin. My thought was that I’d be braver in the future and somehow mentally prepare myself. But can someone really prepare for something like this?

—Kinga

When we think about experiences, we need to think about three types of time: the time before the experience, the time of the experience and the time after the experience. The time beforehand can be filled with anticipation or dread; the time of the experience itself can be filled with joy or misery; and the time afterward can be filled with happy or miserable memories. (The shortest of these three types of time, interestingly, is almost always the time of the experience itself.)

So what should you do? In your case, the time before your sky diving experience will certainly not be cheerful. The time of the experience will also probably not be pure joy. At a minimum, you’re going to ask why you are doing this to yourself. But the time after the experience is likely to be wonderful (assuming that you get out of this alive), and you will get to bask in the way you conquered your fears and relive the view of Earth from above.

So your best strategy was to make the time before the experience as short as possible. It is too late now, but you should have just gone sky diving the moment you got the coupon, which also would have signaled to your boyfriend how much you appreciated the gift.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Early in my career, I wrote a massive Excel macro for the large bank where I worked. The macro (a set of automated commands) would take a data dump and turn it into a beautiful report. It took about two minutes to run, with an hourglass showing that it was working away. The output was very useful, but everyone complained that it was too slow.

One way to speed up a macro is to make it run in the background, invisibly, with just the hourglass left on-screen. I had done this from the start, but just for fun, I flipped the setting so that people using the macro could see it do its thing. It was like watching a video on fast forward: The macro sliced the data, changed colors, made headers and so on. The only problem: It took about three times as long to finish.

Once I made this change, however, everyone was dazzled by how fast and wonderful the algorithm was. Do you have a rational explanation for this reversal?

—Mike

I’m not sure I have a rational explanation, but I have a logical one. What you describe so nicely is a combination of two forces. First, when we are just waiting aimlessly, we feel that time is being wasted, and we feel worse about its passage. Second, when we feel that someone is working for us, particularly if they are working hard, we feel much better about waiting (and about paying them for their effort). Interestingly, this joy at having someone work hard for us holds true not just of people but of computer algorithms, too.

The life lesson should be clear: Work extra hard at describing how hard you work to those around you.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

During a recent hotel stay, I tried to resist temptation but gave in and bought a $5 bag of M&M’s from the minibar. I know from research on pricing that paying a lot for something often makes you experience it as especially wonderful—but that didn’t happen with the M&M’s. Why?

—David

Research does indeed show that higher prices can increase our expectations, and these increased expectations can spur us to more fully enjoy an experience. But there are limits. First, you have probably had lots of M&Ms in your life and have rather set expectations about how good they can be. Second, some high prices are just annoying.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

StartupOnomics 2014

StartupOnomics is an annual gathering to help startups think about human behavior. At the end of the weekend, attendees will walk away knowing how to move the needle on their biggest customer problems…and with some tangible ideas to test and implement immediately.

Apply to StartupOnomics if you are at a company that is trying to improve people’s lives in these ways:

- Helping people live better financial lives (save money, make money, pay off debt)

- Improving our education system, specifically early education system

- Addressing any of the variety of health issues facing society

Our ideal applicant:

- Smart

Handsome*Good-looking 😉- Good sense of humor

- Interested in applying principles of human behavior to help solve big problems

- The company is doing consumer focused products or services

- You are a product leader, designer, marketing manager or data analyst. Two people from your team should plan on attending if you are accepted.

*Please not that the term “handsome” was not meant to exclude females, and that we would be happy with both good-looking males and females.

Apply Here by July 7th

Hindsights: Why Do Tourists Abroad Eat at Subway?

At the port in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico there are wonderful Mexican restaurants and authentic tasty taco trucks. But where might you find the Americans eating? Mostly at the Starbucks, the Subway, and the Johnny Rockets.

This seems puzzling: Why do Americans go abroad and eat at the most generic American restaurants?

One possibility is that these choices are convenient and safe: the American chains have good locations, are familiar, and have fast service. This may have something to do with it, but there’s another explanation to this puzzle—what’s known as the “American Abroad” syndrome. The crux of the syndrome is that Americans abroad end up feeling really American, so they act American.

Psychologists William McGuire and Rohit Despande find that when people are around a different race, group, or nationality, they think about those differences. Accordingly, how they think of themselves momentarily changes. For instance, many Americans may not constantly think of themselves as an American when living in the suburbs. However, when stepping off a cruise boat into a foreign land, their American identity may immediately become obvious.

Once people start thinking of themselves as American (or any group identity), they are more likely to act inline with that identity.

~Troy Campbell~

Enjoy Summer Movies with a Childlike Wonder Again

With the summer movie season officially starting with The Amazing Spiderman 2 (Though arguably it started this year early with Captain America), it’s time once again to enjoy big budget spectacle movies. But as adults sometimes it can be hard to feel the movie magic we felt as children. Don’t fret! Here are a few tips (inspired by research in consumer psychology) on how to enjoy movies with a childlike wonder.

#1 As a kid you had more time for movies. So as an adult, you need to make a little extra time.

When adults see movies, they might talk about the movie for a few minutes afterwards. If they are true nerds, maybe they read a blog or two. But that’s about it. The movie experience starts the night they see it and ends that very same night.

For a kid, the experience doesn’t end when the movie ends. Instead, the movie is an invitation into years of immersion into a fictional world. Kids talk nonstop about movies, force their parents to take them to Toys R Us to buy the action figures, and then expand on those stories through play, reading, fan websites, and video games.

The Fix:

You should make the time to get more involved with a movie world. How “good” you find a movie, can be affected by how much effort you put into it. This means reading blogs about movies and watching the behind the scenes features on the DVDs.

#2 Kids are encouraged to be excited about movies. So, as an adult you need to find friends that encourage that same excitement.

Not only do kids feel a sense of wonder with movies, but they are also encouraged to embrace that sense of wonder. Parents encourage their children to tell them about the things they love. No one encourages adults to talk about movies. The guy in the office next to me has explicitly made it clear that he doesn’t want to hear any more about the awesomeness of The Empire Strikes Back.

This is unfortunate, because the suppression of expression is terrible for enjoyment. Professor Sarah Moore of the Alberta School of Business finds when people explain exciting things in a boring way, they end up finding the content boring. But if they explain it in an exciting way, they magnify their enjoyment. The conclusion: if people do not express their passion with strong emotion, they may lose out on some of the passion.

The Fix:

If you want to enjoy movies more, put on a costume and attend a convention where nerd passion is socially encouraged. Or have a Katherine Heigl movie night if that’s more your thing. Or at the very least just post about a movie on Facebook and start a discussion. The point is, if you share your passion with others you can maintain and grow your passion.

#3 As a kid, everything was magical and new. So, as an adult, you need to find new things.

Remember how impressed you were as a kid by that quarter behind the ear trick? Today you find that completely unimpressive — at least hopefully you do.

The next time you are even slightly impressed by an action movie, think how impressed a kid would be. Kids love things so easily that they probably even thought X-Men Origins: Wolverine was cool.

Scientists find that when people become overexposed to content (e.g., a type of fight scene), our brains stop paying as much attention. Once something is no longer new, our brains tell us to check out, so the joy starts to fade away.

The Fix:

Adults should branch out and start watching slightly “odder” content – I suggest the indie monster film Monsters or a Wes Anderson film. Adults won’t be desensitized to the new type of content, so they’ll likely find more magic and wonder in it. Or, try a more intense movie experience like The Wolf of Wall Street.

#4 Nostalgia is why we love our childhood movies. So as adults we need to create more instantaneous nostalgia.

Nostalgia gets a bad rap publicly. However, nostalgia is a very powerful feeling, and there are many positive reasons to spend some quality time indulging in nostalgia.

The great thing about nostalgia is that nostalgic memories tend to be linked to memories of social connections. For instance people’s memories of Star Wars are wrapped up in memories of their parents showing it to them for the first time or playing “Rebels vs. Empire” with their friends. These connected memories bring about the feelings of warmth, support, and love that fulfill humans’ greatest needs.

You might even think that movies from your childhood were terrible, but love those movies nonetheless. You love those movies because they have meaning to you. The emotional connections and meanings are sometimes more important to you than the quality of the film.

The Fix:

If you want to enjoy modern movies more, you need to make movie-going become more instantaneously nostalgic. So go see the films in big groups. Start a Sunday afternoon movie crew or go to a midnight showing. Again, if you want to enjoy something, you need to change the process by which you enjoy it to make it bigger, more memorable, and more full of social interactions with other fans.

So, next time you go to the movies, see if you can bring back some of the magic from your childhood. Try a new genre of movie, talk about it with your friends after, or just put a little more effort into really enjoying the experience. You may not be a child any more, but with these tips in mind, you just might be able to enjoy the movies like one.

~ Troy Campbell ~

Ask Ariely: On Double Trips, Price Puzzlement, and Rationalizing Rolex

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

—Richard

My suggestion: Buy your sandwich and your coffee, but ask the café to serve you the coffee three minutes later. Then sit with your sandwich and try to aim the wrapper at the trash can—and, no matter how successful you are, get up and walk to the counter to pick your now-ready coffee. If you made the basket, great; if not, pick the wrapper on your way to get your coffee. This way, there is no world in which you did not have to get up after your shot, no counterfactual and no comparison. Happy breakfast.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

- 10 wings for $7.99 with two sauces

- 15 wings for $12.49 with two sauces

- 20 wings for $16.49 with two sauces

- 30 wings for $24.79 with three sauces

- 50 wings for $39.79 with four sauces

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like