Sign up for A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior. It’s not only FREE and open to everyone, but will surely keep you amused for the next six weeks.

Every year, March Madness gives us an underdog story and millions flock to a momentary allegiance with a college they could not locate on a map. In the past it has been George Mason, Virginia Commonwealth University and Butler, and this year we eagerly await a new momentary hero.

So why do we love underdogs?

Well, no matter whether you are Republican or Democratic, work for Microsoft or Apple, or are a janitor or CEO, you most likely see yourself as somewhat of an underdog.

In America, especially compared to other countries, the underdog narrative is an honorable and respectable narrative. From the American patriots in 1776 to the George Mason Patriots in 2006, the Cinderella story, as it is specifically called in the NCAA tournament, has always been an attractive one.

So with underdogs you have 1) a narrative people like and 2) a narrative people see themselves in. Is it any wonder people want to cheer for underdogs? It’s like cheering for yourself.

These serve to energize us with the hope that people like ourselves can do anything. People like to believe that those above us aren’t that great after all, and that people like us are just as good, if not better than the people in power.

In fact, the narrative is so strong that Neeru Paharia, of the Harvard Business School, and colleagues named a psychological effect after it, simply “the underdog effect.” They found that companies gain goodwill from consumers when companies present themselves as a group that has overcame disadvantages through sheer determination. This effect was stronger for people who personally related with the narrative and stronger in cultures (e.g., America) where the narrative was more prevalent.

This narrative dominates American culture not only in sports but in all other popular media. From Luke Skywalker to Cinderella, Americans crave stories about underdogs. Even the more privileged characters in storylines, such as the elite James Bond or billionaire Tony Stark, end up in situations where they must overcome disadvantages through sheer determination.

Even politicians are forced to conform to the narrative, regardless of reality. This is a challenge that proved difficult for Mitt Romney and may have greatly have hurt his campaign.

The underdog narrative doesn’t only sell fiction, politics and sports, it also sells nonfiction books in my field of social science. The nearly unparalleled success of Malcolm Gladwell’s “Outliers” owes a lot of that success to the intuitive appeal of his “10,000 hours doctrine.” Gladwell concludes that if someone spends 10,000 hours at something they can become an expert, implying to readers (who don’t carefully read Gladwell’s other more nuanced chapters) that they can make it just by trying hard.

Hip Hop artist Macklemore of the “Thrift Shop” fame even opens his chart-topping first album with a song called “Ten Thousand Hours.” He directly references Gladwell’s name in the song, chants “Ten thousand hours, felt like thousands hands, they carry me,” and then raps “Take that system!”

Oddly enough, many political pundits on both sides of the spectrum have argued (mostly for political reasons) that such a dream is fading in America. But psychological research shows that when beliefs we value are threatened, we try to find ways to defend such beliefs and keep the belief alive. Believing that an underdog will win in Atlanta this year might be a good way to keep alive that wonderful American underdog dream.

This article was originally published in the Providence Journal and can be read here.

~Troy Campbell~

Sign up for A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior. It’s not only FREE and open to everyone, but will surely keep you amused for the next six weeks.

Sign up for A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior. It’s not only FREE and open to everyone, but will surely keep you amused for the next six weeks.

Sign up for A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior. It’s not only FREE and open to everyone, but will surely keep you amused for the next six weeks.

Today is the day that my free online class on coursera, A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior, opens to the public.

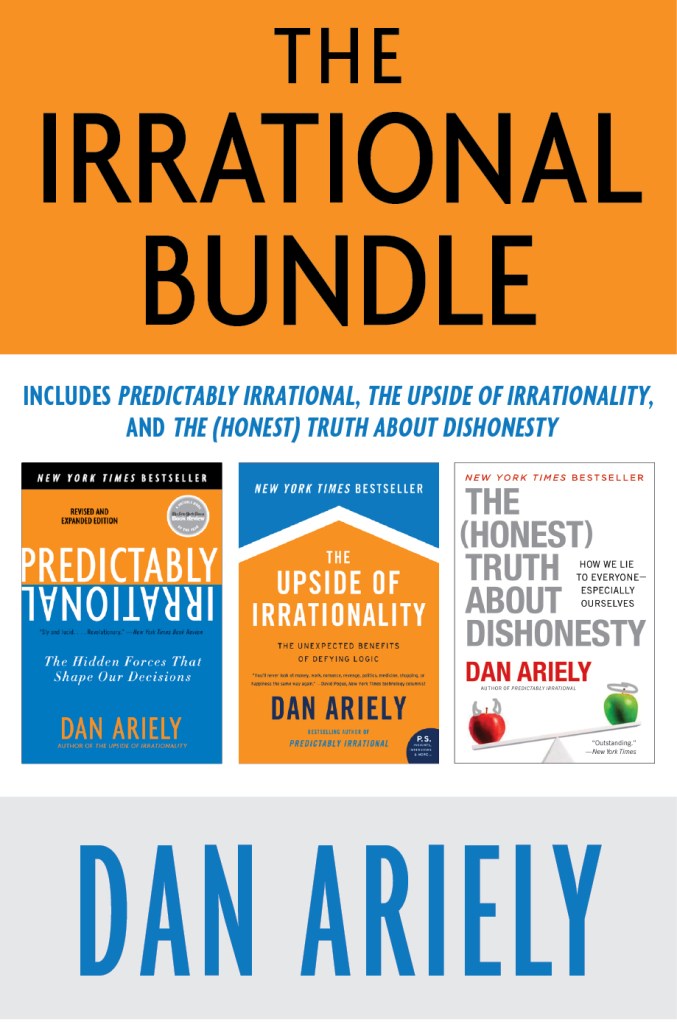

And in honor of this class, my three books will be available as an e-bundle at a discount ($19.99 for all three) until the day after the class starts, March 26th — but only until that date.

You can purchase the e-bundle through Kindle, Nook, iBookstore, Kobo, or Google.

And if you haven’t already signed up for A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior, it’s the perfect time to do it now! It’s not only FREE and open to everyone, but will surely keep you amused for the next six weeks.

Irrationally Yours,

Dan

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, just email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My boyfriend and I have been together for a while, and people ask us whether we’re going to get married. We get along great and love each other very much, but I just don’t see the point of marriage. Why not just live together in a civil union and be happy the way things are? Aside from the cost, is there any point to this elaborate ritual?

—Janet

I have no research on this topic, but allow me to share a story that might help you to think about the question.

When I was 19 and spending time in a hospital in Israel, recovering from severe burns, I had a friend there named David, who had been badly injured in the army while disassembling a land mine. He lost one of his hands and an eye and also had injuries to his legs and some scars. When Rachel, his girlfriend of several months, broke up with him, the other patients in the department were furious with her. How could she be so disloyal and shallow? Did their love mean nothing to her? Interestingly, David was better able to see her side, and he was not as negative as the rest of us about her decision.

Think about Rachel in the story above. Does her behavior upset you? How might your feelings differ if it had been a longer-term relationship, if they were engaged or in a civil union, or if they were married? And how would you behave if you were in Rachel’s position in each of these relationships?

I suspect that your level of scorn for Rachel will depend to a large degree on the type of relationship she had with David. I also suspect that your predictions about your own decision to stick with a partner who just experienced an awful injury would similarly depend on the type of relationship. If your assessment changes when you stipulate that David and Rachel were married, this suggests that publicly saying “for better and for worse” really means something to you.

Obviously, marriage is not some magical superglue for relationships; the high divorce rate is no secret. But marriage can serve a very real purpose by bolstering commitment and feeling in long-term relationships, all of which inevitably hit rough patches. So while I wouldn’t advocate marriage in all situations, I do think it’s worth thinking about the ways in which it can strengthen the bond between people.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When I go to a public bathroom, I often think about which stall I should use. Any advice?

—Cathy

I assume that your practical aim is to figure out which bathroom stall is likely to have been used the least. But what you are really asking is what drives other peoples’ choices in this important domain.

If those who patronize public bathrooms usually choose a stall based on which toilet they think is used the least, they will all choose the one they think is used least—which as a result, ironically, would be that most of them would use the same toilet. Therefore, you would be advised to pick the opposite (i.e., the stall that people think gets the most traffic). Following this logic, if people expect the stall farthest from the entrance to be the most popular, they will avoid using it—leaving it relatively more clean and unused than the others.

But what happens if people are more sophisticated than that? What if they come to the restroom with this same understanding and as a consequence pick what they think is the opposite of what other people think, or the opposite of the opposite?

All of this boils down to a more essential question: How sophisticated do you think other people are?

Personally, I believe people generally take about one step in their logical thinking. So I would say: Choose the opposite of the opposite and select the stall that people think will be used the most.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I enjoy Twitter, but I find that some people tweet very frequently, sometime as often as a dozen times an hour. When their face shows up again and again, I begin ignoring their messages. By contrast, when people tweet just once a day, I’m more likely to pay attention to what they say. Is this just me or does it reflect a larger principle?

—Heidi

I suspect that this feeling is very common. I also imagine that very few people have dozens of interesting things to say a day, much less an hour. Perhaps Twitter is a place where a system based on limits and scarcity (maybe two tweets a day) would be better for everyone.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

I recently came across this video that some talented person made of a study I conducted on wealth inequality a few years back with Mike Norton. It does a great job covering the main findings regarding the differences between what Americans think the distribution of wealth is (somewhat even), what they would prefer (more even than socialist Sweden), and how wealth is actually distributed (the bottom 40% of Americans possessing less than 0.3% of total wealth, the top 20% possessing 84%). The graphs, and a longer explanation, are also available here.

The only thing I wish he emphasized a little more is how similar the results were for Democrats and Republicans, which I found very hopeful. Even with all the ideological polarization in Washington, the moment we ask the question of ideal wealth distribution in a general and less self-interested way, we seem to be a country that cares a lot about each other.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, just email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I was recently approached by a panhandler who asked me for 75 cents, and I gave him the money. I was late for my train, so I didn’t have time to stop and try to understand why he chose 75 cents. But I wonder: Do you think the 75-cent request could be a “market tested” amount, one that yields a higher overall level of “donations” than asking outright for a buck or more.

—Brad

The panhandler could be trying to make a unique request in order to separate himself from the competition. But my guess is that you were more willing to give him money because you inferred things from the specificity of his request.

When someone tells us to meet them at 8:03, we come to a different conclusion about how seriously they mean that exact time as compared with their telling us to meet them at 8 or 8-ish. In the same way, a request for exactly 75 cents may carry a set of inferences about how seriously the person needs the money. It may lead us to think there is a specific reason for the request, like getting enough for bus fare. Plus, even if he asks for 75 cents, it’s likely that people will give $1 and not wait for change.

You could argue that the same principle would apply if he asked for $1.25, but in this case the size of the request might deter some people, and if they don’t have exact change, giving $2 might be too much. This is just speculation, though. If you are willing to volunteer as an experimenter for a few days, we can gather some real data and get to the bottom of this.

What lessons can we draw from this strategy? First, think about the inferences that people make from the exact way that we request something. Second, asking for general help is unlikely to be as effective as asking for exactly what we need.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

In a restaurant where waiters pool their tips, could they actually receive more tips overall by employing a “good waiter/bad waiter” routine, where one waiter is surly and unhelpful, then another waiter steps in who is friendly and goes above and beyond in serving the client? I suspect that the scheme might cause the customer to leave a larger tip for the second waiter, which will ultimately be pooled with the tips of the “bad” waiter.

—David

I agree with your analysis. And for it to work, you don’t even need the waiters to share their tips—they could just alternate roles.

A friend who worked for a large consumer-products company was trying to change the company’s service motto from “we do things right for our customers” to “we mess up the first time, but then we fix it.” His idea (which upper management rejected, by they way) was that when people expect and receive good customer service, it draws no attention, and they just take it for granted (you can think of parallels to romantic relationships as well). But if we give customers a contrast between good and bad service (as at a restaurant), they may start to notice and appreciate good service more.

I suspect that some industries may have already picked up on this idea, and that airport restaurants are leading the charge by providing the training grounds for delivering bad service most effectively.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I graduated from college a few years ago, and since then my social life has been limited to Facebook. And it is far from satisfying.

—James

Facebook has many wonderful aspects, but I agree that it is no substitute for human contact. If you ever feel that nobody really cares whether you’re alive, try missing a couple of student loan payments.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like