Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When I host friends for dinner, can I ask them to help with cleaning up afterward? I hate doing dishes, but maybe it’s impolite to ask guests to share the load.

—Evelyn

I think that you should ask your friends to help. Doing dishes isn’t fun, but if your guests pitch in they will derive satisfaction from knowing they are helping you out. Not only is it a way for them to express appreciation for the meal, but working together on a task is a way of increasing social bonds.

But since the end of an experience is important in determining how we remember and evaluate it, you may want to avoid ending the evening with this chore. Instead, try cleaning up together right after the meal and then invite everyone for a final drink. Of course, that would create a few more glasses to wash, but you would end the evening on a positive note.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

I’ve told my family and friends that I don’t want them to buy me any gifts for the holidays this year—I already have everything I need. I’ve also learned about the bad working conditions for store employees during the holiday season and don’t want to contribute to the problem. Still, I’m worried that by cutting out gifts, I’ll miss the fun and energy of the season. Do you have any suggestions for other ways to show generosity?

—Name

Your commitment to avoiding consumerism this holiday season is admirable, but naturally it would be disappointing to see all your friends having fun and getting gifts while you don’t.

Why don’t you make a list of items you have at home in good condition but don’t want, and ask your friends to make a similar list. On Black Friday weekend, instead of hitting the sales, you could all get together and exchange things on your lists. If you want to have the fun of hunting for bargains, you could even hold an “auction” where you negotiate which items you are willing to trade. This way you will get some new things for the holidays, you will experience some of the fun of shopping and looking for deals, and you will be sticking to your principles.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m shopping for a new car and I’ve been finding it hard to make a decision. Which would I regret more—buying a car I really want but later finding out that I made a bad choice, or not buying the car I really want and later finding out I should have bought it?

—Warren

Research shows that in the short term, we tend to regret actions—in this case, buying a car—more than inactions. But in the long term, we’re more likely to regret the things we didn’t do. Psychologists suspect that this is because the consequences of inaction are uncertain and take much longer to make an impact. So while you might have regrets at first if you buy a car you don’t like, choosing not to buy a car you love would be worse in the long run.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I lead a small startup with an informal human-resources system. To get employees to report expenses accurately, would it be better to create detailed policies or to set out general principles for people to follow?

—Jenna

Setting out general principles is a better approach. Even if you made your company policies very detailed, it’s impossible to anticipate every contingency that might arise, so they will inevitably be incomplete. What’s more, when people are given highly specific rules, it’s easier for them to adhere to the letter of the law rather than to the spirit—telling themselves that they are not misbehaving even when they are. And bureaucracy is the enemy of trust: Every time you make people explain why they should be reimbursed for that extra cup of coffee, you are communicating to them that you don’t trust them.

Instead of creating a list of allowable expenses, try asking people to spend the company’s money as if it was their own. You could also remind them that a rigid system for expenses would make it more difficult for them to be reimbursed, so that in the long run behaving honestly will benefit both the company and its employees.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

There has been a lot of news recently about the potential dangers of e-cigarettes, and some states have even moved to ban them. But obesity is a much bigger public health problem, and the government isn’t trying to ban fattening foods. Why is there a disproportionate response to e-cigarettes?

—Dylan

One of the main reasons is that cigarettes themselves are widely known to be unhealthy, so we are prepared to be suspicious of any product that resembles them. Imagine that, instead of looking like a cigarette, liquid nicotine was mixed with coffee and drunk from a mug. Would people be as eager to ban it? I don’t think so.

Our reactions are often based more on emotion than on logic, and in this case the distrust many people feel toward tobacco and tobacco companies fuels their willingness to believe that e-cigarettes are especially dangerous.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I sometimes think about what it would be like if my husband died. Is this normal?

—Sheila

The evidence I’ve collected in an informal survey of 40 people suggests that, after a few years of marriage, it is perfectly normal to fantasize about your significant other dying. In fact, I found that the vast majority of respondents had thought in surprising detail about how they want their spouse to die. They tended to think about this in terms of a trade-off between how much their spouse was going to suffer and how long the survivor would be expected to mourn.

A sudden death by car accident, for example, minimized the suffering of the victim, but it seemed to demand a long mourning period from the survivor. On the other hand, a prolonged battle with cancer meant extended suffering but allowed the surviving spouse to move on after death. Most people hoped for something in between: a brief illness that would not involve too much suffering for the dying spouse and would allow the survivor to resume their life quickly.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Dear friends,

As part of the research for my next book (yes, it is time to get back to my cooking book), I am collecting stories about cooking or food that illustrate a social science principle. If you have one, I would be grateful if you could share it with me here. This will help me very much and in return, if I will use your story I will send you a book when it is ready and done.

Please submit the story using this link.

Many thanks,

Dan

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My diet goal is to stop eating so many sweets and start eating more vegetables. Would it be easier for me to focus on avoiding what I don’t want to eat or on eating more of what I should?

—Charlotte

Whether you focus on the positive goal or the negative one, the key thing to keep in mind is what social scientists call the principle of “friction”: People tend to follow the course of action that requires the least effort.

What this means is that you should arrange your environment to make it easier to achieve your goals. Place vegetables in a visible spot in your refrigerator and make sure that you serve them first at mealtimes, so you will have to expend minimal effort to eat them. Do the opposite with sweets—place them out of sight or on the highest shelf in the pantry, making them harder to reach.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

At my company, management is encouraging employees to seek advice and feedback from one another to improve our performance. But in my experience, it’s really hard to get people to give you useful, honest feedback, because they are afraid of giving offense. Is there any way to make this process work, or is it going to be a waste of time?

—Patricia

You’re right that people are unlikely to give accurate and honest feedback to their co-workers; there is a lot of social pressure against offering criticism, and people who receive it are likely to take offense.

But while it’s often hard to change our behavior in response to feedback, it turns out that giving advice can be more useful than receiving it. A recent study published in the journal Psychological Science shows that people who gave advice were more motivated when it came to challenges like controlling their tempers, saving money and finding jobs. In a follow-up study, high-school students who gave advice earned higher grades than those who received it.

This research suggests that giving advice can be a powerful confidence-booster—so your company’s initiative might be useful overall, even if people don’t act on the advice they receive.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve noticed that jokes that are meant to be funny sometimes come across as painful or offensive. Is there a way to know whether a joke is going to hurt people’s feelings?

—Pete

According to the behavioral scientist Peter McGraw of the University of Colorado, Boulder, jokes are funny when they involve “benign violations”: They transgress a social norm but not so much that they become objectionable. The trick is to hit the sweet spot between amusing and offensive.

For example, The Onion recently ran the headline “Harvard Officials Say $8.9 Million Donation From Jeffrey Epstein Was From Brief Recovery Period When He Wasn’t A Pedophile.” When I asked my friends how funny they found this headline, the ones from Harvard found it much less funny.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My retired parents and I usually go out for lunch every other Sunday. We have been taking turns paying the check, but I know that I make more money than they do. Should I start paying for all the meals or at least cover the tip when they are paying?

—Andrew

Since you’ve established a custom of taking turns paying for meals, I think you should continue on that basis. Think of these meals as gifts that you are giving each other: The purpose of gift-giving is to help strengthen relationships rather than a strictly financial exchange. If you are worried about potential strain on your parents, you can offer to pay some of their other bills or give them a yearly cash gift, but I would separate the issue of their finances from the weekly tradition that you have established.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am applying for a CFO role at a public company. I am competing for the job with several other candidates, and the interviews with the board of directors will take place over the course of a week. Should I try to schedule my interview early in the week, late in the week or somewhere in the middle?

—Eric

There are two countervailing forces here. One is the exhaustion of the people interviewing you, which will likely increase over the course of the week. When people get tired, they’re more likely to make negative decisions. There’s a disturbing study on judges’ decisions to grant parole, showing that they are twice as likely to accept a prisoner’s application when they decide in the morning than at the end of the day. From that perspective, it’s better for your interview to take place on Monday.

On the other hand, the “recency effect” says that people are more likely to remember the most recent information. If the board is making its decision after the last interview, it would be to your advantage to be later in the week, so that you’ll still be prominent in their memories. The question is which force is going to be stronger. If you think the process is going to be exhausting for the people interviewing you, go early in the week; if not, try to go late.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

In general, what do you think are the domains where we make our best and worst decisions?

—David

People are generally better at making decisions about the physical world than they are when it comes to the mental world. That’s because when we make physical mistakes we see the consequences right away—think about the consequences of bad driving—while mistakes that we make in the mental world take much longer to appear—such as the consequences of making bad choices in elections.

This difference came home to me on a recent trip to London. The British have been able to create a material environment that is just amazing, from the beauty of the buildings to the quality of public transportation. Yet the political crisis in the U.K. suggests that when it comes to making decisions about the future of their country, they are finding things much tougher to manage.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Understanding the human mind is key to the better design of artificial minds.

A short report based on a paper by Darius-Aurel Frank, Polymeros Chrysochou, Panagiotis Mitkidis, and Dan Ariely

Technology around us is becoming smarter. Much smarter. And with this increased smartness come a lot of benefits for individuals and society. Specifically, smarter technology means that we can let technology make better decisions for us and let us enjoy the outcome of good decisions without having to make the effort. All of this sounds amazing – better decisions with less effort. However, one of the challenges is that decisions sometimes include moral tradeoffs and, in these cases, we have to ask ourselves if we are willing to allocate these moral decisions to a non-human system.

One of the clearest cases for such moral decisions involves autonomous vehicles. Autonomous vehicles have to make decisions about what lane to drive in or who to give way at a busy intersection. But they also have to make much more morally complex decisions – such as choosing whether to disregard traffic regulations when asked to rush to the hospital or to select whose safety to prioritize in the event of an inevitable car accident. With these questions in mind it is clear that assigning the ability to make decisions for us is not that easy and that it requires that we have a good model of our own morality, if we want autonomous vehicles to make decisions for us.

This brings us to the main question of this paper: how should we design artificial minds in terms of their underlying ethical principles? What guiding principle should we use for these artificial machines? For example, should the principals guiding these machines be to protect their owners above others? Or should they view all living creatures as equals? Which autonomous vehicles would you like to have and which autonomous vehicles would you like your neighbor to have?

To start examining these kinds of questions, we followed an experimental approach and mapped the decisions of many to uncover the common denominators and potential biases of the human minds. In our experiments, we followed the Moral Machine project and used a variant of the classical trolley dilemma – a thought experiment, in which people are asked to choose between undesirable outcomes under different framing. In our dilemmas, decision-makers were asked to choose who should an autonomous vehicle sacrifice in the case of an inevitable accident: the passengers of the vehicle or pedestrians in the street. The results are published under open-access license and are available for everyone to read for free at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-49411-7.

In short, what we find are two biases that influence whether people prefer that the autonomous vehicle sacrifices the pedestrians or the passengers. The first bias is related to the speed with which the moral decision was made. We find that quick, intuitive moral decisions favor killing the passengers – regardless of the specific composition of the dilemma. While in deliberate, thoughtful decisions, people tend to prefer sacrificing the pedestrians more often. The second bias is related to the initial perspective of the person making the judgment. Those who started by caring more about the passengers in the dilemma ended up sacrificing the pedestrians more often, and vice versa. Interestingly overall and across conditions people prefer to save the passengers over the pedestrians.

What we take away from these experiments, and the Moral Machine, is that we have some decisions to make. Do we want our autonomous vehicles to reflect our own morality, biases and all or do we want their moral outlook to be like that of Data from Star Track? And if we want these machines to mimic our own morality, do we want that to be the morality as it is expressed in our immediate gut feelings or the ones that show up after we have considered a moral dilemma for a while?

These questions might seem like academic philosophical debates that almost no one should really care about, but the speed in which autonomous vehicles are approaching suggests that these questions are both important and urgent for designing our joint future with technology.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

I started college a couple of weeks ago, and I find myself very preoccupied about whether the people I’m meeting like me. Do you have any advice about how I can relax around people?

—Bronwyn

You will be relieved to know that most of us tend to underestimate how much people enjoy our company. In 2018, Erica J. Boothby and colleagues published a paper about the “liking gap”—the difference between how much we think other people like us and how much they actually like us. In one of their studies, they asked first-year college students to rate how much they liked a given roommate and how much they believed their roommates liked them, starting in September and continuing throughout the school year.

They found that participants systematically underestimated how much they were liked. In fact, it wasn’t until May, after living together for eight months, that people accurately perceived how much they were liked. So try to focus your social energy on spending quality time with friends and don’t worry too much about the outcome.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I work for a nonprofit organization that offers mindfulness retreats for teens. Our tuition model is that we request 1% of a family’s income, up to $2,000, for a week-long retreat. We feel that this model is fair, but some higher-income families object to paying more than others for the same service. Why do they feel this way, when the cost is such a small share of their income?

—Tom

Our perception of what is fair depends to a large degree on what we’re being asked to give up to achieve a fair outcome. In your arrangement, people with more money are being asked to pay more, so they are likely to see a fixed price for tuition as being more fair than a sliding scale—and vice versa for families with less money.

One way to try to overcome this bias is what the political philosopher John Rawls called the “veil of ignorance.” In this approach, people are asked to design an imaginary society they will have to live in, without knowing whether they are going to be rich or poor. This means that they have to decide what is fair before they know how much they will personally stand to gain or lose from any given arrangement—for instance, the tax rate. Maybe you can try an exercise of this sort related to tuition as part of your mindfulness teaching.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

I have an aging but perfectly fine car and waste a lot of time pining for something more modern and comfortable. But I haven’t found a new model I love, and with technological improvements happening so fast, cars are getting better every year. Should I wait for the perfect car to come along or should I compromise and buy something now?

—Alex

My sense is that if you don’t like any of the available options, it means you’re not yet ready to make a change. Happiness isn’t just about what we have and don’t have; it’s also about not constantly looking for something better. Why don’t you decide that you won’t look at new cars for a certain period—say, two years—and then give yourself a three-month window to research a purchase. At the end of that time, you will pick the best option available. This way, you won’t waste time and energy on an open-ended search.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am a widow, and my friendships are very important to me. But many of my friends are couples, and each year I end up buying birthday gifts for both the husband and the wife, plus an anniversary gift. While I always get a nice present in exchange on my birthday, the balance of gift-giving seems unfair. Is there a more evenhanded way to exchange gifts?

—Carol

It’s very hard to shift social norms about gift-giving, especially when a pattern is well established. The best approach might be to try to replace the current norm with a new one. For example, what if you told your friends that you are concerned about the environment and want to try to reduce your level of consumption and waste, so you are planning to start giving cards instead of gifts. Ask them to help you with this commitment by giving you cards in exchange. This way, you would be appealing to a moral principle, rather than telling the that all you are trying to do is to save SOME money.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m planning a vacation, and I’m considering a prepaid, all-inclusive resort, so that I won’t have to worry about the cost of every drink and sandwich. But I’m concerned that the all-inclusive package won’t be as good an experience as some of the other, pay-as-you-go options that I’m looking at. Is prepaying always the best choice?

—Saurabh

You’re certainly right that an all-inclusive resort isn’t always the highest-quality option. But you have to remember that what’s most important is whether you’re going to enjoy the experience you have. Constantly having to make decisions about what to buy can detract from your vacation experience, even if the hotels or restaurants you end up patronizing are of better quality.

In general, when you make a decision, it’s better not to ask “Am I choosing the absolute best option?” Instead, you should consider your enjoyment of the experience as a whole, including your ability to relax and your peace of mind.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I grew up in a working-class household, and I’ve been upwardly mobile in my career, but I’ve recently begun to feel that my job is meaningless. Should I think about my work merely as a way to make money to survive? Or would it be better for me to look for a job that I can take pride in as part of my identity?

—Ella

The research is very clear that finding meaning in your job is necessary for happiness. At the same time, if too much of your identity is tied up in your job, it can make you more vulnerable to work-related stress. A study conducted in 1995 by Michael R. Frone, Marcia Russell and M. Lynne Cooper found that people who strongly connected their identities with their jobs were much more sensitive to work stressors than those who thought about their work in a more casual and detached way.

Ideally, you should look for work that gives you a sense of pride and meaning, but you should also remember that a job doesn’t define you, and that there are other, equally important parts of your identity.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Hello all,

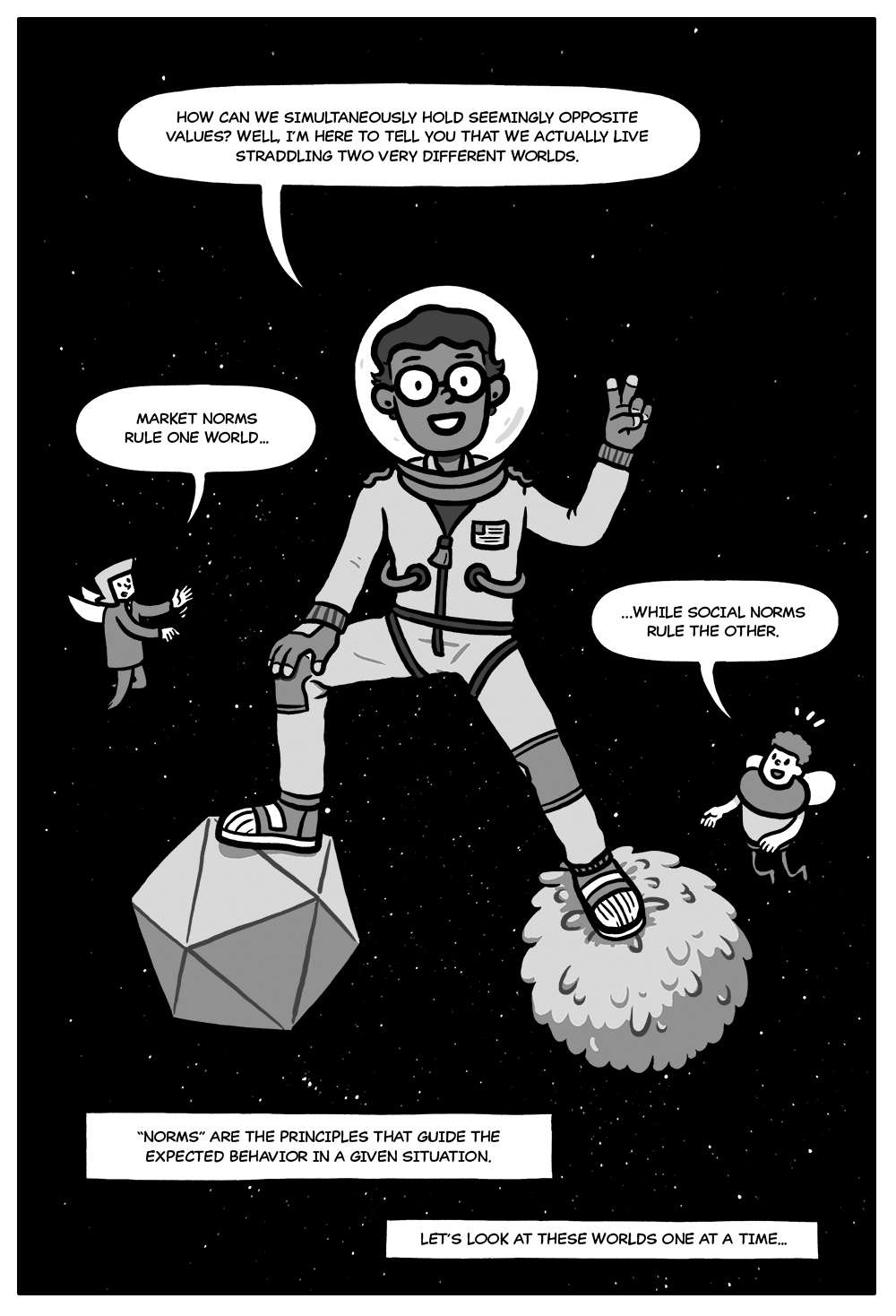

I’m excited to share with you my new graphic novel with illustrator Matt R. Trower, Amazing Decisions: The Illustrated Guide to Improving Business Deals and Family Meals. This book will help you understand how to navigate the complex and curious interaction between social norms and market norms… and make better decisions for it!

Please watch this video to understand more, and find the book here on Amazon or in your local bookstore!

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Does the fact that so many Democrats are running for President in 2020 make it more difficult for voters to choose among them? I’m especially interested in politics, and even I find it hard to compare each candidate’s positions. I wonder if many Democratic voters will simply give up on paying attention to the primaries.

—Tracy

In behavioral science, we call this phenomenon “the paradox of choice.” While many people report that they like having more choices, having too many choices can end up making it impossible to make a decision at all. For example, when people are given a lot of flavors of jam to choose from, they tend to sample more flavors, but they are less likely to actually buy one of them. In the case of the Democratic primaries, the number of candidates is certainly overwhelming, and I think it is likely to decrease voter turnout.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

During a recent doctor visit, I was asked to sign an agreement saying that if I missed a future appointment I would have to pay a $50 fee. I thought this was excessive and refused to sign. Does this kind of policy really get more people to show up for medical appointments?

—George

Negative incentives—in other words, punishments—are more complex than they seem and can backfire. One of my favorite studies on this topic is by the economists Uri Gneezy and Aldo Rustichini, who showed that when a day-care instituted a fine for late drop-offs, parents became even less likely to arrive on time. Instead of viewing the fine as a punishment, parents saw it as a way to pay for the right to be late, and they took advantage of this service without guilt.

In your case, I would expect to see a similar result: Patients might feel more entitled to miss appointments if they know they can pay a fee for it. In addition, the system will probably make patients even more furious when doctors are inevitably late, since it implies that the doctors think their own time is more valuable than that of their patients.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Do people’s salaries tend to accurately reflect the value they contribute to society? Can we assume that if someone makes a lot of money, they are adding significantly more value than someone who makes only a little?

—Richard

On the contrary, there are many people who create a lot of value and don’t get paid much, as well as many who create very little value and get paid well. One of the best examples of this mismatch is teachers. A paper by Raj Chetty and colleagues in the American Economic Review estimated how much of an impact teachers have on the future of the students in their classes.

They found that students with strong teachers are more likely to attend college, have higher lifetime salaries and are less likely to become pregnant as teenagers. They estimated that replacing a teacher in the bottom 5% with an average teacher would increase their students’ lifetime income by $250,000 per classroom. Yet obviously, teachers don’t make anywhere close to that figure. Maybe one day we will evolve as a society and base people’s salaries on their actual contribution to the common good.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like