Ask Ariely: On Cutting Cola, Loving Labor, and Engaging Investments

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been drinking soda for the past 15 years, and I’m trying to stop. I’ve tried phasing it out by switching to water some of the time and having a soda here and there, but I usually cave in to temptation by the end of the day. Is there a better strategy?

—Andrew

Getting off soda gradually isn’t going to be easy. Every time you resist having one, you expend some of your willpower. If you’re asking yourself whether you should have a soda whenever you’re thirsty, you’ll probably give in a lot and gulp one down.

So how can you break a habit without exposing yourself to so much temptation and depending on constant self-control to save you? Reuven Dar of Tel Aviv University and his colleagues did a clever study on this question in 2005. They compared the craving for cigarettes of Orthodox Jewish smokers on weekdays with their craving on the Sabbath, when religious law forbids them to start fires or smoke.

Intriguingly, their irritability and yearning for a smoke were lower on the Sabbath than during the week—seemingly because the demands of Sabbath observance were so ingrained that forgoing smoking felt meaningful. By contrast, not smoking on, say, Tuesday took much more willpower.

The lesson? Try making a concrete rule against drinking soda, and try to tie it to something you care deeply about—like your health or your family.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been living with a roommate for six months, and we divide up the household responsibilities pretty evenly, from paying the bills to grocery shopping. He says, however, that he feels taken for granted—that I don’t acknowledge his hard work. How can I fix this?

—C.J.

This is a pretty common problem. If you take married couples, put the spouses in separate rooms, and ask each of them what percentage of the total family work they do, the answers you get almost always add up to more than 100%.

This isn’t just because we overestimate our own efforts. It’s also because we don’t see the details of the work that the other person puts in. We tell ourselves, “I take out the trash, which is a complex task that requires expertise, finesse and an eye for detail. My spouse, on the other hand, just takes care of the bills, which is one relatively simple thing to do.”

The particulars of our own chores are clear to us, but we tend to view our partners’ labors only in terms of the outcomes. We discount their contributions because we understand them only superficially.

To deal with your roommate’s complaint, you could try changing roles from time to time to ensure that you both fully understand how much effort all the different chores entail. You also could try a simpler approach: Ask him to tell you more about everything he does for the household so that you can grasp all the components and better appreciate his work.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Is it useful to think about marriage as an investment?

—Aya

No, because the two things are profoundly different. You never want to fall in love with an investment because at some point you will want to get out of it. With a marriage, you hope never to get out of it and always to be in love.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Career Center Incentives, Painful Pricing, and Colorful Communication

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I work with liberal arts college students, many of whom don’t use their school’s career services early enough, if ever. What’s the best way to get reluctant students to participate in early career-discovery activities? Is there any way to make this fun or at least less overwhelming?

—Lisa

One of the challenges here is the perennial problem of “now versus later.” “Now” is at the forefront of our minds, and college students are no exception: What am I going to major in, how can I finish this 30-page paper on time, how can I balance basketball practice with my work-study job? All of these academic, social and financial concerns create cognitive demands right now—and make it hard to focus on career planning, which students tend to think about as years away.

You aren’t likely to convince busy and distracted students to assign a higher priority to the distant future. Instead, you could try to create structures that make career exploration feel like a “now” concern. Could a course require students to interview alumni in related fields at the career center? Could students fulfill certain distribution requirements by visiting the career center each semester? Could the career center pitch its services as tools to help students find summer jobs and internships?

Don’t present the career center as an optional, supplementary service to help find jobs after senior year. Try to match it to students’ immediate needs.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Uber infuriates me every time it declares “surge pricing.” I know that behavioral economics teaches us that framing is important. Would Uber be better off using the term “discounted pricing” during off-peak periods and “regular pricing” during peak periods?

—Paul

Yes, framing matters a lot. If Uber had its own fleet of cars and was just selling rides, your suggestion would be a great way to limit their customers’ ire. But Uber doesn’t have cars of its own and relies on motivating drivers to show up and offer rides. The same “surge pricing” that angers you appeals to Uber’s drivers, helping the company to get more of them on the road when it needs them.

The ideal framing would be to have Uber call its higher fares “surge prices” for its drivers and “regular prices” for its passengers—but that is manipulative and deceptive, so I wouldn’t suggest it.

As a message to customers, “surge pricing” also compels us to take immediate action. Imagine that you open the app and see that the current price is 1.5 times the usual fare. Do you wait and try again later, or do you worry that the price might leap up to 1.8 times that fare and order your Uber immediately?

Our deep desire to avoid regret—staring at a screen, stranded, as we watch prices soar—is so strong that it usually gets us to press the button even faster. So while customers hate surge pricing, it has important benefits for Uber.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

After a recent date, I’ve been wondering whether I should sign my next text to her with the word “love” or with an emoticon of a heart. Which one is she likely to take more seriously?

—Deb

Emoticons are a wonderful, colorful, rich way to express ourselves. But because emoticons can be interpreted in multiple ways, they are a less clear form of communication. So don’t hide behind the ambiguity of the emoticon. Use the word.

Love,

Dan

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Tipping Out, Question Quality, and Stockholm Syndrome

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Some restaurants have made news recently by eliminating tipping. But will the long-term effect be worse service?

—Phil

I wouldn’t expect a decrease in the quality of service. I’m not sure that tipping is a particularly motivating reward to begin with. For one thing, tips in many restaurants are often pooled among employees. That means that the gratuities are averaged across workers, so individual waiters won’t immediately or strongly experience the benefits (or punishments) that stem from superb or lousy service. Furthermore, statistical modeling by Ofer Azar of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev found only a small relationship between tips and service quality. He concluded that other factors had more influence on the type of service that you’re likely to get.

If anything, I suspect that eliminating tipping and giving waiters a stable, living wage would improve the quality of service. Without the vagaries of tips, restaurant employees would have a consistent, dependable income—and, perhaps, higher job satisfaction. That would help lower employee turnover and raise profits for the restaurant. These are all fine reasons why more restaurants should get rid of tipping.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve found that the most interesting people to talk to are often obsessed with a topic, whether it is food, music or economics. How can I increase my likelihood of meeting this type of person? What questions can I ask to uncover people’s passions when I meet them?

—Riley

When we meet someone new, most of us have a puzzling tendency to start the conversation as if we are exchanging resumes. We typically don’t go beyond questions like “What do you do?” and “Where are you from?” But the key to a good conversation isn’t meeting the right type of person; rather, as you suggest, the trick is asking questions that allow almost anyone to reveal who they are, what they have experienced and what they are passionate about.

Often, the questions that can help put a bit more depth into our conversations are more complex than the standard “What do you do” approaches. They also require more openness, effort and daring from the person asking the questions. Think of asking new friends about their ideal dinner companion, living or dead, or about the heroes they most admire or about the aspects of their life for which they’re most profoundly grateful. It may be a little unfamiliar, but such questions do get conversations going in very different directions.

I know from personal experience that starting conversations by asking nonstandard questions isn’t always easy. But as you get more used to asking such questions, your discussions will become more interesting. We all want lives filled with meaning, so we should get beyond the default of vacuous conversation-starters.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently learned about the Stockholm syndrome, in which captives develop sympathetic feelings for their captors. I know that the parallel isn’t exact, but does this dynamic operate in marriages too, with both partners (in a metaphorical and emotional sense) seeing themselves as imprisoned in a way and the attraction to the person “capturing” them creating a stronger relationship?

—Abhinav

Sorry, but the Stockholm syndrome just isn’t a sensible way to think about marriage—not least because marriage lacks the glaring power difference between the person doing the capturing and the person being captured. But now that I think about it, maybe the syndrome is a good way to think about spending the holidays at your in-laws, and perhaps this glue helps keep families together during those trying times.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Swift Sales, Debt Distortions, and Beauty Beliefs

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A European online retailer recently changed its delivery policy from offering multiple delivery times to offering free one-day delivery on all purchases. Before the change, one-day delivery was available but cost 10 euros. Is this retailer smart to shift to this quicker, cheaper delivery arrangement?

—Thilo

Many businesses are trying to deliver their wares more quickly, but it isn’t always a good idea. When we want something, we usually think that faster is better and now is ideal. But imagine that you had the choice of attending a concert by your favorite band either tonight or in two weeks. The vast majority of people would prefer to wait the two weeks. We recognize that the concert itself is only one part of the experience: Not only will the anticipation be fun, it also will help us to enjoy the performance more.

In the new delivery approach you describe, the retailer is basically forcing everyone to pay for faster shipping (the list price of your goods will necessarily include the cost of faster shipping) and forgo the joy of waiting. Neither is ideal, especially if your purchase happens to be an exciting treat rather than a dreary necessity. Many online retailers would do better to help their consumers savor the anticipation rather than deliver so quickly that we lose some of the fun of our purchase.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m attending graduate school in famously pricey New York City. I’ve been living with my husband in a small studio apartment, but a huge, gorgeous one-bedroom just opened up next door for my final year of school. Of course, this perfect apartment costs considerably more than we can afford; we would have to take out more loans to cover the extra rent.

So is the difference between $150,000 in student loans and $156,000 in loans (a 4% additional expense) significant enough for us to remain in our underwhelming apartment—or, down the road, will any concern we feel about the financial difference matter less than our excitement about our great new place?

—Andrew

The way we ask ourselves questions about spending money influences our answer. You could have asked whether this move is worth $6,000 or if it is worth the difference between $150,000 and $156,000—which, sensibly, keeps the focus on the absolute amount of $6,000. But your choice to frame the extra expense as a percentage difference suggests that you really want to move. And if you’re so eager to move that you are willing to distort your economic reality to feel better with the answer you want, maybe you should go for it.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What is the essence of what we perceive as beauty? And what would it be if you were in charge of such things?

—Sinclair

Our brain is largely attuned to changes, and that, I suspect, includes beauty. We often find beauty in shifts or transitions that are smooth but not too smooth: the way a melody changes, the arc of your beloved’s raised eyebrow, the imaginary line at the beach where the waves strike and retreat, the place where the mountains curve and the cliffs abruptly depart from the ocean.

But since you asked what I would want the definition of beauty to be—it would be slightly balding, slightly chubby, middle-aged university professors.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

The Switching Type

Companies in the electric power industry want to keep their current customers and attract new ones. But when customers move to a new residence, they often switch providers. So, what’s the most effective way to convince these customers to switch back? A recent study suggests that goal-oriented go-getters are motivated not just by saving money, but by completing a task. Julie O’Brien, a research associate at Duke’s Center for Advanced Hindsight, discribes the “switching type” a personality trait and a novel way to appeal to customers.

And the iTunes link:

https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/the-switching-type/id420535283?i=1000377340352&mt=2

Higher Education, Higher Incomes…Opportunity for all?

Having a college degree can dramatically increase a young adult’s income. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2014 the median earnings of young adults (ages 25-34) with a bachelor’s degree were 66 percent higher ($49,900) than the median earnings of young adults with only high school diplomas ($30,000).

Anyone who performs well in high school can apply to college, and there are many scholarships, financial aid, and other support programs available to help make college an option for everyone. But does this help?

Topic 4 in Fair Game? asked users to think about whether household income is related to the likelihood of getting a college degree and what that relationship should look like in a fair world.

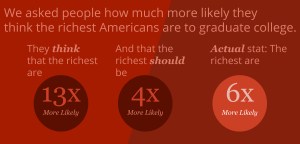

On the whole, our users estimated that the wealthiest 25% of society would be 13x more likely to get a college degree than the poorest 25%. In reality, the wealthiest 25% are about 6x more likely to get a college degree.*

How much more likely do people think the wealthy should be to get a college degree, in a fair world? 4x more likely.

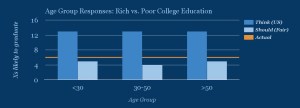

Estimates for the greater likelihood of getting a college degree were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair. There may be hints of a difference in what people think is fair, with 30-50 year-olds reporting 4x likelihood, while other age groups said a 5x likelihood would be fair. One possible explanation for this difference is that people in the 30-50 age range may be actively planning or paying for their children’s college expenses.

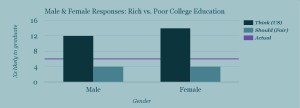

What about gender? Males and females differ in their estimates of the greater likelihood of getting a college degree for the top 25% of income, estimating 12 and 14 times greater likelihoods, respectively. But they agree in what they think a fair likelihood would be — 4x.

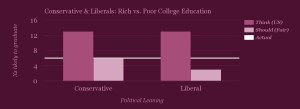

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal estimate the same (13x) greater likelihood of getting a college degree for the wealthy. In terms of how much more likely the top 25% of income should be to get a degree, in a fair society, conservatives answered 6x more likely and liberals answered 3x more likely. So although their understanding of the world is similar, their notions of fairness, for this topic, are very different.

Together, the data reported here suggest that people overestimate the gap in the likelihood of getting a college degree. And they would reduce the size of the gap that they perceive. There are many factors that contribute to the gaps in attainment of a college degree. Family income based factors are certainly an important contributor. But there are also decisions about whether to apply to college at all, what type of college to attend (e.g. for profit vs. nonprofit), how to access and pay back loans, and what kind of support a student may have from their social networks. Sometimes, just the paperwork involved in applying to college can overburden a prospective student and derail the process. It is encouraging then that low-cost interventions have the potential to improve college opportunities for low-income students.

Given the potential economic benefits that would result from more low-income students getting a degree, what are other possibilities that might work to increase the proportion who ultimately do get a degree?

What do you think? Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

“Equal Pay for Equal Work”

It’s a simple statement but it represents so much more than just four words. For many people, it is a rallying call for closing the gap between men’s and women’s wages, ultimately achieving the goal of pay equity, and protecting a notion of basic fairness.

Others question the very idea of what equal work means, with some people arguing that women make different career choices compared to men and that any gap is merely a reflection of those choices. But in the United States, there are many historical examples of inequality affecting women including: denial of property rights, the right to vote, the ability to obtain higher education, and barriers to particular occupations and specialized careers.

Given the complex history of women’s equality in the U.S., we wanted to find out what people think about the current state of working women and their pay relative to men. We focused on the gender wage gap for topic 2 of Fair Game?, our new app that asks users what they think about the world as it is today and what they would want in a fair world.

Surprisingly, people tend to overestimate the gender wage gap and believe women earn 73% of men’s income. In reality, women are estimated to earn 79% of men’s income.

How much do people think women should be paid in a fair world? 93% of men’s income.

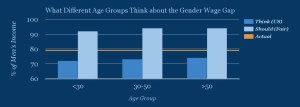

Overall, responses did not dramatically differ by the age of the user.

How does your own gender relate to what you think about this? Male and female users both overestimated the magnitude of the gender wage gap, with men thinking women currently earn 74% of men’s salaries, and women estimating that they earn 70% of men’s salaries.

There was closer agreement for the question of what a fair wage gap should be, with males preferring 93% and females preferring 94% of men’s salaries. On the whole, both genders perceive a gap to exist in the United States and would substantially – but not completely – close that gap in a fair society.

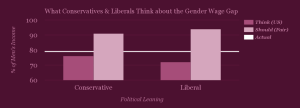

And can we observe differences in views according to political beliefs? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal only differed by 4% in terms of what they believed the gender wage gap to be, and 3% in what they thought it should be in a fair world. Conservatives estimate women’s salaries to be 76% of men’s, while liberals put that percentage at 72%. In terms of what they think would happen in a fair society, conservatives consider 91% and liberals consider 94% to be a fair ratio of women’s to men’s income. Despite these relatively small differences, on average, the increase in women’s salary thought to yield fairness would be 15% for conservatives vs. 22% for liberals.

The gender wage gap is a topic that deserves careful consideration. Although a single number represents an average for all women, the number varies substantially once we consider factors including race, age, education, profession, career trajectory, childbirth status, and U.S. state of residence, to name a few.

There is also likely to be some gender role stereotyping at play in the results we received, with many of our respondents probably assuming that the burden of childcare would or should fall disproportionately on women.

This is a complex topic, but we can learn from some efforts to equalize opportunities in the workplace for women. A program in the Canadian province of Quebec provided an interesting natural experiment, demonstrating that subsidized daycare could support an upsurge in employment of women that in turn boosted economic output to a level that more than paid for the childcare subsidy costs1.

A final consideration is how long it will take to close the gender wage gap, given the progress that has already been made. One measure of improvement (the upward trend since the 1960’s), predicts the gap to close by 2059. But if a recent slowdown in the trend persists, the gap would not close until 2152. What other efforts do you think might be worthwhile to pursue to help close this gap, sooner or later?

And please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

- Fortin, Pierre et al. (2012). Impact of Quebec’s Universal Low-Fee Childcare Program on Female Labour Force Participation, Domestic Income and Government Budgets. Sherbrooke: Research Chair in Taxation and Public Finance, University of Sherbrooke.

Fair Game? How many average workers’ salaries does it take to pay the CEO?

Inequality is an important topic and one that politicians and scholars spend a lot of time thinking about. But what does the general public think about inequality and the many ways it manifests in daily life? And how do factors like age, gender, or political leanings relate to our views on inequality?

Those are the questions we are exploring with Fair Game?, our new app that asks users what they think about the world as it is today and what they would want in a fair world.

We’re asking users about 13 different topics related to inequality, from wage gaps to opportunities for education, and will be sharing our findings every few days now through mid-November.

Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play. We’ll release a new question every few days until we get through all 13.

You can think about the first topic right now.

So far, the data show a consistent knowledge gap.

Our users estimate that the average CEO’s pay is equal to 151 average worker salaries. In reality, the average CEO makes the same as 303 average workers combined. What do people think CEOs should be paid in a fair world: the same as 72 average employees combined.

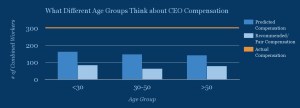

We also found some interesting patterns in what people think.

Younger people estimate the ratio of CEO pay to average worker pay to be larger than others do, and also think a larger ratio is fair. Perhaps younger people have lower salaries and therefore think the average worker’s salary is lower? Or they are looking ahead to larger, CEO-like salaries in the future, and that influences what they think is fair?

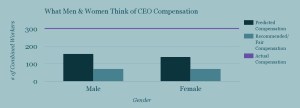

What about gender?

It is notable that males and females arrive at the same number for what would be fair (72 average worker salaries for each CEO), but differ in what they think currently exists in the world (158 for males vs. 140 for females). Perhaps the gender wage gap influences the perception of what salaries are in the world?

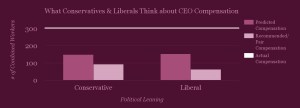

And political leaning?

People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal give similar estimates of what the current CEO to average worker salary is (149:1 and 152:1, respectively). But political leaning makes a big difference in what people think what would be fair. Liberal respondents believe 63:1 would be fair, whereas conservative respondents believe that 93:1 would be fair.

It is encouraging that political leaning does not dramatically change our respondents’ perceptions of the world. Both conservatives and liberals underestimate the magnitude of executive pay relative to worker pay in the United States. But their differing assessments of what would be fair suggests that conservatives and liberals might choose different approaches to reducing the executive-to-worker pay ratio.

Executive compensation is by no means a simple issue. In fact, the 2016 Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to researchers who considered how motivational factors should be related to pay, bonuses, stock compensation and the timeframe of company performance in order to achieve optimal levels. One of the winners, Bengt Holmström, told a reporter after hearing he had won, that he thought executive bonuses were “extraordinarily high” and compensation contracts were too complicated.

Has it always been like this? The ratio of executive pay to worker pay was 20-to-1 in 1965, when CEOs earned an average of $832,000 annually, compared to $40,200 for workers (adjusted for today’s dollars). In 2000, the number peaked at 376-to-1, and has since settled back down to the recent level of 303-to-1 (and some estimates are as low as 216-to-1). This increased ratio means that CEO compensation has risen dramatically over the past few decades, but the average worker compensation has not. In 2014 the average CEO made $16,316,000 compared to the $53,200 made by the average worker.

In an effort to promote greater transparency, the Securities and Exchange Commission will soon require every publicly traded company in the United States to disclose this ratio. A recent bill proposed in the California Senate calls for instituting a sliding scale of corporate taxation, with companies paying different tax rates based on their ratios and sharper increases for those with CEO to average worker pay ratios greater than 100-to-1. Other proposals for reducing the ratio and social ramifications of large gaps in companies include greater profit-sharing across employees and a more consistent relationship between (long-term) performance and bonuses.

Ask Ariely: On Celebratory Savings, Tools for Temptation, and Anticipating Activities

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My wife and I recently had our first child. We know that friends and family, especially grandparents, like to buy gifts for children for birthdays and holidays. But we have set up a college savings account for our child and would much prefer to have our loved ones put money into this account rather than buy things that our child doesn’t really need. How can we encourage this more rational behavior?

—Kyle

Though giving money is often more economically efficient than giving stuff, the feeling of social connection that we get from gift-giving is higher when we give something tangible. If I were you, I would try to provide the gift-givers with a chance to do a bit of both. You can ask them to buy something small for your child and also to put some money in the college fund.

If you want an even higher proportion of the money to go to the college fund, buy a nice book with blank pages and on its cover write your child’s name and the word “future” (“Dan’s Future,” for example). You can then ask each gift-giver to put money in the college fund and, at the same time, to share some advice for life by writing on one page of the book. This way, there will be a physical reminder of their gift (the book and the advice), but more of the money will go to the college fund.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am trying to stop using Facebook because it only wastes my time and makes me feel bad about myself. But despite repeated attempts to stay away from my Facebook page, I keep coming back to it. I think part of the reason is that I’m so impulsive. Do you have any advice on how I might finally break my Facebook habit?

—Maryam

My recommendation is to create some sort of “Ulysses contract.” As you will recall from Homer’s ancient tale, Ulysses knew that if he allowed himself to hear the tempting calls of the Sirens, he would follow them and in the process kill himself and his crew. So he asked his sailors to tie him to the mast of his ship and put wax in their own ears. Ulysses thus protected himself from temptation by making it impossible to take action when temptation appeared. He didn’t have to summon his willpower to resist.

Maybe you can make your own Ulysses contract by asking a friend to change your Facebook password and not to tell you what it is for a month. This will give you a chance to see what life without Facebook feels like and to decide if that is indeed what you want. If it is, you can then go ahead and delete your account—and you will be free of Facebook.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I hate waiting for anything. I get very impatient when I have to wait for food in a restaurant, for my new iPhone, for the next time I will meet a good friend, etc. Is there anything I can do to make it less painful to wait?

—Maya

Sometimes anticipation can be a pleasurable part of the experience. Imagine, for example, that you could get a kiss from your favorite movie star. Would you rather get the kiss in the next 30 seconds or in a week? When faced with this question, most people prefer to wait because, in the end, a kiss is just a kiss, but waiting for a unique kiss can be wonderful. My advice is that you try to get into such a mindset for other experiences as well, and instead of thinking about waiting as a delay, think about it as an opportunity for anticipation.

P.S. I got this question from you a few months ago, and I hope that you enjoyed anticipating my response.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Freelance Feedback, Teacher Tardiness, and Meal Money

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m a freelance copywriter. I like not having to hold a regular day job, but I never get performance assessments, never learn what I can do better, and never know why people stop hiring me. So to improve my performance, I’ve been thinking about sending my clients a short survey about the quality of my work. But I worry that if they’re forced to think about it, they might say, “Hmm, she’s not actually that friendly” or, “Hmm, her work is just average”—and stop hiring me. What do you think?

—Dana

Ask for the feedback. You might lose some clients in the short term, but the surveys should help you improve your work in the long term.

The trickier question is how to ask for feedback in a way that minimizes negative perceptions about your work (and maybe even spurs your clients to see your work more positively). You can do this by asking your clients to list 10 ways you could improve your work.

My guess is that your clients will easily find one or two ideas for how you could perform better, which will be useful feedback. But after that, they will find it increasingly difficult to come up with pointers until, perhaps at suggestion five, they will run out. By then, they will start thinking, “I can’t find many things wrong with this copywriter—so she must be great.” By creating the expectation that there should be 10 ways to improve your performance and having them come up well short of that, you incline them to think more positively about your work.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

At my school, in an effort to discourage teacher absenteeism and tardiness, we’ve instituted a carrot-and-stick system: Teachers gets a monetary reward if they are on time every day of the week, but if they are late on even one day, they lose a corresponding amount from their wages. Does this system make sense? Do you think it will work?

—Miriam

Yes and no. Assuming that the reward money is a substantial amount, the teachers will probably try hard to be there on time. On the other hand, since you’ve made the reward all-or-nothing (perfect attendance or a penalty), your teachers are also likely to experience the “what the hell effect.”

Imagine, for example, a teacher who was late for class on Monday. What will be his or her motivation for being on time for the rest of the week now that they’ve missed the mark on perfect attendance? Less dedicated educators may well shrug and start showing up late on purpose. I’d predict that teachers will start each week trying to be punctual, but once they slip, they’ll give up completely. You would probably be better off with a less punitive approach that is more compatible with a learning environment.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m an excellent cook who’s planning to host a gourmet, home-cooked meal for about 10 people. I’d like to use the pay-what-you-want method. So what’s the best way to ask for the money? Should I ask people to pay up front or at the end, and should it be in public or anonymous?

—Labanya

Based on the principle of reciprocity, you should ask for the money at the end of the meal (when people will know how good your food was). I would give people envelopes with their names on them at the end of the evening and ask them to put their payment inside. This way, your guests will be accountable to you but won’t know exactly how much their fellow diners paid. Have fun.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like