It’s not a lie if…”

Based on George Costanza’s advice to Jerry Seinfeld:

THE LIST

1. It’s not a lie if you believe it.

2. It’s not a lie if it doesn’t help you.

3. It’s not a lie if it hurts you.

4. It’s not a lie if it helps someone else.

5. It’s not a lie if it doesn’t hurt someone else.

6. It’s not a lie if everyone expects you to lie.

7. It’s not a lie if the other person knows the truth.

8. It’s not a lie if nobody can prove it.

9. It’s not a lie if you don’t get caught.

10. It’s not a lie if you don’t need to tell another lie to cover it up.

11. It’s not a lie if you were crossing your fingers.

12. It’s not a lie if you proceed to make it true.

13. It’s not a lie if nobody heard you say it.

14. It’s not a lie if nobody cares.

Irrationally yours

Dan

Before television and the internet, political candidates had two primary means of getting their image out into the public: live appearances and campaign posters. And given the limited reach of the former, posters were a crucial element in political strategy. How else were candidates supposed to project an image of decisiveness and gravitas?

So when Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for governor of New York in 1928, his campaign manager had thousands of posters printed with Roosevelt looking at the viewer with serene confidence. There was just one problem. The campaign manager realized they didn’t have the rights to the photo from the small studio where it had been taken.

Using the posters could have gotten the campaign sued, which would have meant bad publicity and monetary loss. Not using the posters would have guaranteed equally bad results—no publicity and monetary loss. The race was extremely close, so what was he to do? He decided to reframe the issue. He called the owner of the studio (and the photograph) and told him that Roosevelt’s campaign was choosing a portrait from those taken by a number of fledgling artists and studios. “How much would you be willing to pay to see your work hung up all over New York?” he asked the owner. The owner thought for a minute and responded that he would be willing to pay $120 for the privilege of providing Roosevelt’s photo. He happily informed him that he accepted the offer and gave him the address to which he could send the check. With this small rearrangement of the facts, the crafty campaign manager was able to turn lose-lose into win-win.

This story reminds me of the famed trickster, Tom Sawyer, who duped the neighborhood boys into trading him toys and apples for the chance to whitewash a fence. When one of the boys taunted him for having to work instead of going swimming, Tom responded with all seriousness, “I don’t see why I oughtn’t to like it. Does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?” Then when the boy asked for a chance to try it, Tom hemmed and hawed until finally the boy said he would give up his apple for a chance to whitewash the fence. Once Tom had one taker, outsourcing the rest of the work to other boys was a snap.

I conducted a similar experiment in a class I was teaching on managerial psychology. One day, I opened my lecture with a brief reading of a poem by Walt Whitman, after which I informed the students I would be doing a few short poetry readings, and that space was limited. I passed out sheets of paper providing students with the schedule of these readings along with a survey. Half of the students were asked whether they would be willing to pay $10 to come listen to my reading; the other half were asked whether they would be willing to listen to my reading in exchange for $10. Sure enough, those in the second group set a price for enduring my poetry reading (ranging from $1 to $5). The first half, however, seemed quite willing to pay to attend my poetry reading (from $1 to about $4). Keep in mind that the second group could have turned the tables and asked to be paid for listening to my recitation, but they didn’t.

In all of these situations, people (the campaign manager, Sawyer, and myself) were able to take a situation of disadvantage or ambiguous value and spin it to their (my) advantage. Once Sawyer pretended to be unwilling to part with the privilege of whitewashing, other boys wanted it, because obviously Tom was hoarding all the fun. When I told my students that space was limited and gave a suggested price for the recitation, I created the idea that this was an experience they would definitely want to have (as opposed to the other group, to whom I insinuated that listening to my reading of Whitman might be less than enjoyable).

I think Twain summed this strategy up best when he wrote the following about Tom: “He had discovered a great law of human action, without knowing it – namely, that in order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain.”

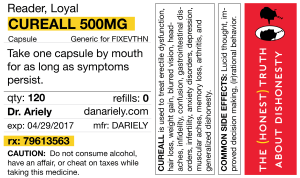

I’m excited to announce an innovative new therapy that will be released in tandem with my new book The Honest Truth About Dishonesty. I developed it with a team of medical doctors and behavioral economists to treat a broad spectrum of disorders. Cureall (Fixeverything) works to combat the tendency toward self-deception and dishonesty, which, like bacteria in the human body, affect everyone (some more than others).

Cureall is indicated for symptoms ranging from nervous headaches (which often result from faking our credentials to employers) to gastrointestinal disorders (a common side effect of seeing family and friends commit a dishonest act). Talk to your doctor about getting a prescription for Cureall, and watch as your lucidity, honesty, and energy levels go through the roof.

We’ve known for a while that both the processes and products of the pharmaceutical industry need to be regulated. The roots of this regulation stretch back over a century, but it’s been since the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments were passed in 1962 in response to thousands of severe birth defects caused by the drug thalidomide that drug manufacturers were for the first time required to prove the effectiveness and safety of their products to the FDA before marketing them. Since that time, we’ve created huge obstacles in terms of time, money, and evidentiary rigor between drug manufactures and the market; on average, it takes about 10-15 years and hundreds of millions of dollars for a drug to make it from the lab to the pharmacy. And as we come to a greater understanding about conflicts of interest and prescribing patterns, we also regulate the activities of pharmaceutical companies at even smaller level, such as when and to whom they can give pens or free lunches.

In stark contrast, we have the financial industry. In this domain, no one needs to prove the safety or effectiveness of financial products such as derivatives and mortgage-backed securities. This is because we make two major assumptions about such products based on economic theory: we presume first that they have sound internal logic and second, that the market will correct problems and mistakes if something goes awry with one of these new inventions.

In theory we could make the same argument for pharmaceutical products as well. Medications are also developed based on logic—in this case chemical and biological—and a group of experts assume that they will be effective based on this logic. We can also assume that the market would weed out bad medications, just as it weeds out unsuccessful companies and products. How would it do this? Well, people who take bad medications would become ill or die, other people would find out, and over time this process would preserve the demand for medications that work well—the same logic that is applied to financial products. Despite these parallels, there’s an incredible lack of symmetry in how we view regulating these markets.

People remain highly suspicious of one market (pharmaceutical), and far less so of the other (financial), but when we compare the systems in broad strokes, their similarities are evident. A paper I read recently got me thinking more about this comparison. In both cases, the industries in question get more money if people use more of their products, and both use salespeople to convey information about their products to consumers. So far that’s pretty standard fare in business. Less common is the similarity that these salespeople have incentives such that they benefit from selling the product, but lose nothing when it fails. Moreover, in both cases the product is complex and difficult to understand, even at the expert level. Additionally, there is substantial asymmetry in the knowledge of salespeople versus that of consumers. And in both cases, the stakes are very high, with physiological health and financial health in question. And while death rarely occurs as a direct result of financial products, the damage they can do is immense (see the financial crisis of 2008).

Yet we apprehend the dangers inherent in a free pharmaceutical market while remaining generally oblivious to those in the financial. No one protests along libertarian lines of letting pharma be free, or shouts from a podium that if the government just stayed out of our treatments and medications, amazing and innovative new cures would suddenly appear. Why then don’t we see the need to regulate the financial market?

I believe that one of the reasons for this discrepancy is that the casualties and damage done in the pharmaceutical domain are far more apparent. When things go badly in medicine, it’s easier for us to quantify them and make clear causal connections. Whereas in the financial market it’s generally the case that lots of people lose some money, but people rarely lose everything. Moreover, in the financial market, there are never just losers, there are always winners as well—someone will gain a lot from a losing transaction, and that’s frequently chalked up to how the system works. With pharmaceutical losses, the injury or death of patients far exceeds any gain the company might make (and then lose in litigation). Also, with medications, the counterfactual is generally much stronger. There are people who took a drug and those who didn’t, and often a clear comparison of the difference emerges. In economics it’s far more difficult to make a causal connection, after all, there is still debate over whether the first and second bailouts helped anyone other than the institutions that got paid directly.

Given the similarities between the markets, and the differences in how we tend to regard them, I think we need an FDA-like entity and process for financial products, because if we don’t have a counterfactual, we can’t compare and measure the value of their products. We could call it the FPA, for Financial Product Administration. One example of a financial tool that the FPA could test is high frequency trading. Companies are going all out to profit by being the fastest to buy and sell stocks, owning them for fractions of a second; they even go so far as to buy buildings closer to the stock market to make trading faster. The logic behind high frequency trading is that companies can take advantage of even tiny price fluctuations. And it’s possible that in principle they’re adding to the efficiency of the market, but it’s more likely that they increase volatility, and frighten people off the market, and therefore have a negative effect. It’s an understatement to say that this strategy is focused on the short term, whereas investment ideally is about a longer-term commitment. But regardless of one’s beliefs on whether high frequency trading is ethically sound, it would be nice to know for sure if it makes the markets better or worse off before allowing it.

By the way, one thing I appreciated most about the paper that inspired this post is that the authors are from the University of Chicago—home of the free market champions. That’s a departmental seminar I wouldn’t mind sitting in on.

When I first moved to the U.S. for graduate school (which was a long time ago), I was very intrigued by and excited about the tax system and tax day. I envisioned it as a matter of civic engagement, a yearly ritual where citizens reflected on their contribution to the common pool of resources—for better and for worse. I imagined that people would consider the benefits of taxes—being able to fund schools, build roads and bridges, care for the poorest members of the community, and fund the defense of the U.S.—while at the same time watching for wastefulness and protesting against it. And indeed this is how I looked at tax day for my first few years here.

Fast forward to when I finished graduate school and started making a real income, then I began to see April 15th the way most other people do. I realized that the tax code is so complex and aggravating that instead of making people consider values and social issues, their contribution to society, and government waste, it is mostly a season of shared grumbling and annoyance trying to get all your records together in time. With all of this complexity and ambiguity (is taking your sister for dinner while she’s in town and discussing work projects a legitimate business expense? What if she gives you a good idea that you later use?), the only bonding we have on tax day is over the tedium of figuring out how much we owe and over the continual worry of whether we have done things correctly or not. So instead of promoting civic mindedness, the way the U.S. tax system is structured now highlights the small details of filing taxes. As a result, all of our attention is directed toward ending the irritating procedure, and in the process trying to find as many loopholes in the tax code as possible in order to minimize how much we pay.

So how can we fix this problem? The first step is to simplify and clarify the tax code to make the process less confusing. The process of figuring and filling out tax forms is so exasperating it’s hard not to direct that feeling toward someone or something—and generally speaking, that something is the agency that seems responsible for your suffering, which in this case is the IRS. After all, it’s difficult to maintain a cheerfully civic-minded outlook, or even an even-keeled neutral outlook, in the face of such frustration.

Now imagine the simplest, least irritating approach to taxation. The least bothersome way of paying taxes is to have it done for you; for instance, in Israel, the government takes taxes out of people’s income before they even receive their salary. This means that in Israel, no one really knows their gross pay, but they do know their net pay, which makes them much more realistic about what they make. Generally speaking, the opposite is true in the U.S., where people know their gross but not net pay.

This is one idea, and it certainly would simplify things, but it would also nullify the idea of tax day as a day of citizenship and a time of reflection. So while we want to minimize the procedural pain of tax day, we don’t necessarily want to eliminate the possibility of thoughtful and critical participation in government that it provides. To make it a more beneficial experience, I think citizens should be asked how they want the government to spend their tax money. I don’t mean in the larger sense of voting for a political candidate and his or her economic ideology, nor do I mean the total amount that an individual pays in taxes; rather, I think there should be a section on tax forms that prompts the taxpayer to decide how to allocate 10% of his or her taxes. The choices could be among education, clean energy, health care, defense, roads and infrastructure, and so on. Not only would this give taxpayers a more apparent role in deciding where their money goes, it would avoid the problem of missing the forest for the trees.

With a less frustrating and more participatory tax system, it’s possible we could remake tax day into a more constructive and less arduous occasion. And maybe (maybe) we could get the government to be more responsible.

For now though, we should all look around at what our taxes pay for—the roads, the streetlamps, the police and fire stations—and remember that paying taxes is just part of life.

Happy tax day!

Will Rogers once said that “The income tax has made liars out of more Americans than golf” and I worry that he was correct. During his confirmation hearing to become the Treasury Secretary, it was revealed that Tim Geithner failed to pay Medicare, Social Security, and payroll taxes for several years while he worked for the International Monetary Fund (IMF). When asked by Senator John Kyl (R AZ) during the hearing about the (more than $40,000) “mistake,” which Geithner blamed on the tax software he was using, he replied, “it was very clear that this was an avoidable mistake… You’re right. I had many opportunities to see it.” But he didn’t, apparently, and that was that.

There are many problems here—one of which is the possibility of a double standard that allowed Geithner to get away with this entirely (I am not sure if this is the case or not). I suspect that if he had he been working for a domestic monetary agency, that is, the IRS, he would have faced heavy prosecution, fines, and almost certainly been fired. Also, as the future head of the Treasury, we might hope that he understands the tax code well enough to do his own taxes. Part of his defense, was, of course, that the code is too complex. Which is true, but in light of this, and his own errors, we might then hope he would be more aggressive about reforming the code, which he has not. The worst part of it, however, is the personal example he provided to the rest of the American taxpayers: do your taxes wrong, omit a few things, and if they catch you all you need is to pay it back — it’s basically okay.

I’m not calling for punishing Geithner (retribution isn’t necessarily helpful, not to mention it’s a little late), but as we draw closer to tax time, it’s worth recalling this incident and how it might affect the American public. In the research my colleagues and I have carried out on dishonesty, we’ve found repeatedly that people become more likely to lie and cheat after witnessing the dishonest behavior of others. In one of our experiments, we tested to see how participants would respond to a blatant act of dishonesty in their midst—would they think they too could cheat and get away with it, or would they perhaps straighten up and fly righter than ever? To find out, we gave participants 5 minutes to solve as many mathematical problems as possible (where they were instructed to find which two numbers out of 12 add up to 10).

In the control, where no cheating was allowed, the average student solved 7 problems, which gave them a pay off of $3.50 out of a maximum of $10 (if they solved all 20 problems). To see how witnessing and act of dishonesty would affect participants, we had one student—a confederate named David—stand up after only a minute and claim he’d solved all 20 matrices. The experimenter merely responded that in that case he could take his earnings and go. So how did the participants respond to this display when asked to self-report the number of matrices they solved? By cheating a whole lot: they claimed an average of 15 correct answers, more than twice the average score when cheating was not allowed.

Seeing someone cheat for their own benefit and then get away with it clearly has an impact on our moral behavior—loosening it to a substantial degree.

So, what does this experiment means for paying taxes? It means that the more we see politicians—the people who make our laws—fudge their taxes (which seems to happen continually), the more likely the rest of us are to adjust our understanding of what is right and wrong about paying our taxes, and do the same.

But there is hope. When we ran the same experiment with one slight difference, we found that dishonesty decreased dramatically. This time, instead of looking like all the other participants, who were students at Carnegie Mellon University, we had our confederate wear a sweatshirt that located him within a different social group. This time h was wearing a University of Pittsburgh sweatshirt (Carnegie Mellon’s neighboring and rival university). When the dishonest act was committed by a person from an out-group, we found that cheating decreased dramatically to the lowest level in all the experiments (participants claimed “only” 9 correct problems).

What this means is that if we think of ourselves and our politicians as being part of the same social group, we might follow their footsteps when we hear about another politician or celebrity who hasn’t paid taxes in years. On the other hand, if we don’t think that we belong to the same social group we might not feel more justified in our own moral indiscretions, and instead be extra careful not to be confused with this other, not so moral, social group.

So the moral of the story is: when you settle in to work on your taxes in the next few weeks, try not to think about the individuals who cheat on their taxes—and if you can’t avoid thinking about them, at least try to separate your own social group from theirs.

Go forth and be financially virtuous.

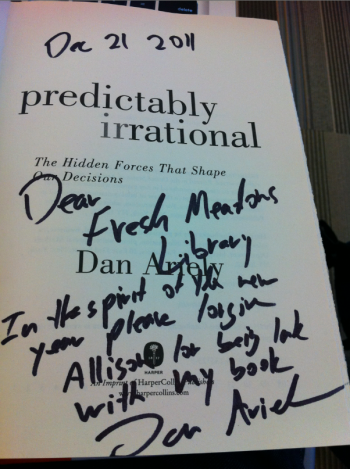

Dan Ariely is the James B Duke professor of Psychology and behavioral Economics at Duke University and the author of (the soon to be released) The Honest Truth About Dishonesty.

I travel a great deal so I frequently find myself in the company of TSA agents who check my boarding pass, remind me to remove my shoes, jacket, belt, laptop, liquids, and all items from my pockets (including the previously inspected boarding pass), and then screen these things, as well as myself. Every time I find myself standing in line, in my socks, I inevitably contemplate the efficiency of the system. It’s only half an hour or so per flight, but when you multiply that number by all the people traveling in the United States, it’s a tremendous amount of time, effort, and money. And this comes not only from the TSA, but also in the form of lost productivity of all the people standing in line in various states of undress. One has to wonder whether it’s worth it.

It’s likely that on an individual level, we’re merely annoyed by the time and hassle of the present security routine, after all, it’s difficult to imagine how many resources are being used as you hurry through the lines. Lucky for us, this organization made a fantastic flowchart to help us see how much time and money we’re spending collectively on TSA, and, more importantly, what kind of results that investment is yielding. Judging from the price (over $60 billion) versus results (very few that are discernable), the question is: what do we do? Clearly we want to be safe and we want to prevent any terrorist activities, but it doesn’t seem that the current system is working, to say nothing of efficiency.

Perhaps in this situation, more is less. That is, maybe if we’re willing to give up more information about our travels and our lives, we’ll have to endure less time-consuming and haphazard scrutiny at the airport. For example, I recently had an interview with U.S. Customs and Border Protection as part of the Global Online Enrollment System (GOES), which preauthorizes approved frequent travelers to enter the US more quickly. I allowed them to do a background and credit check, and then met with an officer for an interview so that he could determine whether I posed any security risks (I’m happy to say I do not). Essentially, I opted for a reduction in privacy in return for not spending half an hour several times a week in line. For now it only applies to in-bound international flights, but I hope it will become more widespread.

At bottom, we have to give up some freedom and information in exchange for security. There’s no avoiding it. So the question is whether we want to do that in half-hour, invasive (not to mention ineffective) increments, or to go through a longer process once that looks further into our lives. Because the cost of the former comes is in small, redundant bits, we tend to overlook it, but in terms of hassle and time spent collectively, the second is a far better option.

That said, similar approaches to cutting time and money spent on security checks for domestic travel might be worthwhile. If individuals could agree to being tracked to a higher degree in order to gain quicker passage through security lines, it would allow TSA (or perhaps another group in charge of security) to know more readily who is and is not on flights. That way we could stop the inanity of having to take off our shoes, being x-rayed, and limiting liquids to theoretically non-explosive amounts.

After all, when you consider the approach to security so far, who knows what the next step might be—will we have to wear certain clothes only, carry only certain kinds of luggage, or no luggage at all? Instead we need a comprehensive approach that addresses concerns more fully, rather than the reactionary, piecemeal approach we have at present.

Imagine that you have a flight at 8:00 in the morning. Which would be worse, arriving at the gate, breathless, at 8:02, just after they’ve closed the door, or at 10:00, thanks to a couple unplanned delays in your morning. Obviously, the first scenario would cause far more misery, but why? Either way you’re stuck at the airport until the next flight, eating the same bad, overpriced food, missing whatever you were supposed to do after your planned arrival, whether that’s meetings or a stroll on the beach.

The difference between the two scenarios is the intensity of the regret you would feel—a great amount in the former and a lot less in the latter. As it turns out our happiness frequently depends not on where we are at the moment, but how easily we perceive we might be elsewhere, or in another, better situation. With the missed flight, you’re in the airport either way, but when it’s a close call, you can think of a dozen little things that would have changed the situation, and each one brings a pang of regret. So, the closer we are to this other possibility, what we refer to as counterfactual, the unhappier we become.

While there are plenty of things in life that cause disappointment and aggravation, consider the case of Costis Mitsotakis, a resident of Sodeto, Spain, who was the only person in this 70 household village who did not receive a share of the $950 million lottery payoff. The story is this: every year the homemaker’s association of Sodeto sells tickets to all the residents, and in 2011, their number won first prize (shared with 1,800 other winning tickets, but still an immense payoff for a tiny, economically depressed town). When the townspeople heard the news, they ran outside, and were congratulated over a megaphone by their jubilant mayor. But soon it was discovered that one resident hadn’t bought a ticket—Mr. Mitsotakis, who had moved to Sodeto for a woman with whom things did not work out, was overlooked when the homemakers made their yearly rounds.

In this case, the counterfactual looms incredibly and painfully large. If only they hadn’t skipped his house or he had run into them at some point—the smallest earning from the lottery in the village was $130,000, and some won more than half a million dollars. If that wasn’t bad enough, the reminders of this alternative outcome will last for the rest of his life, or at least as long as he remains in Sodeto. Mr. Mitsotakis will be continually reminded of the tiny difference in events between his life now and what it would have him. If I were him, maybe I would simply move. This would probably decrease his happiness in the short term, but in the long run I think his life would be much better, and much less regretful.

So, next time you miss a flight, are first in line after tickets sell out, or get stuck in traffic after trying out an alternative route home, just remember, your situation may be frustrating, but it’s not like you lost half a million dollars and it is not as if you will keep on remembering this for the rest of your life.

At a coffee shop in Bluffton, South Carolina, people have been spontaneously paying for future customers’ drinks on a fairly consistent basis. Sometimes, those who are not even looking to buy coffee for themselves will come in and donate money for future (anonymous) customers.

future customers’ drinks on a fairly consistent basis. Sometimes, those who are not even looking to buy coffee for themselves will come in and donate money for future (anonymous) customers.

While certainly unique, this may not be too surprising when viewed under the lens of behavioral economics — and could suggest an interesting business model. Let’s consider a hypothetical coffee shop that chooses to employ a strictly “pay-what-you-want-for-other-customers” pricing strategy, in which customers can only leave money to be used by other customers, and are allowed to leave as much (or as little) as they would like. In turn, their drinks are paid for by previous donations.

First, there are a number of examples in the scientific literature (and in the real-world) of the benefits of pay-what-you-want pricing systems. Allowing people to pay the price they want can sometimes result in people paying more money than they would if a standard price was requested for any particular product or service.

Second, recent research by Elizabeth Dunn, Lara Aknin, and Mike Norton shows that spending money on others can have a more positive impact on one’s happiness than spending money on oneself. So this may mean return visits by customers who wish to get that extra boost in happiness that they do not get from places where they buy their own selected product(s).

Third, Dan Ariely has studied how powerful the idea of “free” can be; in short, people love free things. Receiving a “free” drink in our hypothetical coffee shop (paid for by another customer) should be more desirable than directly paying for the drink.

At this hypothetical coffee shop with a “pay-what-you-want-for-other-customers” pricing strategy, customers may have an experience in which they get to enjoy a “free” product (good for that customer), get a boost of happiness from buying something for others (good for that customer…and the customer(s) who get to spend that money), and may wind up spending more money overall than they would have under a traditional pricing scheme (good for the coffee shop). Thus, allowing people to pay what they want for other customers may potentially lead to a lot of good all around.

There are certainly many risks that come along with a “pay-what-you-want-for-other-customers” pricing system. But if the events of the coffee shop in South Carolina are any indication, such a pricing strategy may just be irrational enough to work.

~Jared Wolfe~

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like