A talk I gave at PopTech

The 7 Habits of Highly Ineffective People

The thing about habits is that for good and bad they require no thinking. An established habit, whether getting ready for work in the morning or having a whiskey after, is a pattern of behavior we’ve adopted—we stick to it regardless of whether it made sense when we initially adopted it, and whether it makes sense to continue with it years later. From a human irrationality perspective this means that something we do “just once” can wind up becoming a habit and part of our activities for a longer time than we envisioned.

To get some insight into this process, consider the following experiment: We asked a large number of people to write the last two digits of their Social Security number at the top of a page, and then asked them to translate their number into dollars (79 became $79), and to indicate if in general they’d buy various bottles of wine and computer accessories for that much money. Then we moved to the main part of the experiment and we let them actually bid on the products in an auction. After we found the highest bidders, took their money and gave them the products we calculated the relationship between their two digits and how much they were willing to pay for these products.

Lo and behold, what we found is that people who had lower ending Social Security numbers (for example 32), ended up paying much less than people who had higher ending Social Security numbers (for example 79). This is basically the power of our first decisions: if people first consider a low price decision (would I pay $32 for this bottle of 1998 Cote du Rhone?) they end up only willing to pay a low amount for it, but if they first consider a high price decision (would I pay $79 for this bottle of 1998 Cote du Rhone?) they end up willing to pay a lot more.

So this is the double-edged sword of habits, they can save us time, energy and unpleasant thinking, but on the other hand, it’s all too easy to start down an unwholesome path. Now onto “ The 7 Habits Of Highly Ineffective People”…

1) Procrastination. Joys untold attend this particular bad habit. And it’s one people indulge in all the time, exercise, projects at work, calling the family, doing paperwork, and so on. Each time we face a decision between completing a slightly annoying task now and putting it off for later, battle for self-control ensues. If we surrender, procrastination wins.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with delaying unpleasant tasks at work from time to time in order to watch a (crucial) football game at the pub with friends. But, the problem is that as we get close to our deadline we start thinking differently about the whole decision. As we stay up all night to finish a task on time we start wondering what were we thinking when we succumbed to the temptation of the football game, and why didn’t we start on the task a week earlier. Moreover, as with all habits one procrastination leads to another and soon we get used to watching deadlines as they zoom by.

2) The planning fallacy. This is more or less what it sounds like; it’s our tendency to vastly underestimate the amount of time we’ll require to complete a task. This hardly needs illustration, but for the sake of clarity, recall the last time you delegated time to a complex task. Cleaning your flat from top to bottom (couldn’t take more than two hours right? Wrong.); finishing the paper or project at hand (who knew the people in department X could be so impossibly slow?). The problem is that even if we try to plan for delays, we can’t imagine them all. What if the person you’re working out a deal with gets hospitalized? What if an important document gets deleted or lost? There are infinite possible delays (procrastination of course being one of them), and because there are so many, we end up not taking them into account.

3) Texting while driving. Let me start by saying that in my class of 200 Master’s students, 197 admitted not only to doing this regularly, but also to having made driving mistakes while doing so. Also, one of the three abstainers in the class was physically blind, so we should not really count him as a saint, and who knows maybe the other two were liars. Texting while driving is clearly very stupid. If we were not intimately familiar with our own Texting behavior, we might think that it’s insane to think that anyone would knowingly increase their chances of dying 10 fold rather than waiting a few minutes to check email, but this is the reality. Moreover, the issue here is not just Texting, it is much more general than this particular bad habit. The basic issue has to do with succumbing to short-term desires and foregoing long-term benefits. Across many areas in our life, when temptation strikes we very often succumb to it (think about your commitment to always wearing a condom when you are not aroused and when you are). And we do this over and over and over.

4) Checking email too much. If it seems that there’s too much about email on this list, I assure you, there isn’t. Checking email is addictive in the same way gambling is. You see, years back the famous psychologist B.F. Skinner discovered that rats would work much harder if the rewards were unpredictable (rather than a treat every 5 times they pressed a bar, one would come after 4, then 13, etc). This is the same as email, most of it is junk, but every so often, it’s fantastic: an email from the woman you’ve been chasing for instance. So we distract ourselves from work by constantly checking and checking and waiting to hit the email jackpot. And to be perfectly honest, I’ve checked my email at least 30 times since starting writing this article.

5) Relativity in salary. The fatter a sea lion is, the more sea lionesses he has in his harem. He doesn’t need to be immense, just slightly bigger than the others (too fat and he won’t make it out of the water). As it turns out, it’s the same for salaries; we don’t figure out how much we need to be satisfied, we just want to make more than the people around us. More than our co-workers, more than our neighbors, and more than our wife’s sister’s husband. The first sad thing about our desire to compare is that our happiness depends less on us, and more on the people around us. The second sad thing is that we often make decisions that make it harder for us to be happy with our comparisons: Would you prefer to get a 50,000 pound salary where salaries range from 40,000-50,000 or a 55,000 pound salary where they’re between 55,000-65,000? If you’re like almost everyone, you’d realize that you would be happier with the 50,000 pound salary, but you would pick the 55,000.

6) Overoptimism. Everyone, except for the very depressed, overestimates their chances when it comes to good things like getting a raise, not getting a divorce, parking illegally without getting a ticket. It’s natural—no one gets married thinking “I am so going to be divorced in 4 years”, and yet a large number of people end up getting divorced. Like other bad habits, overoptimism is not all bad. It helps us take risks like opening a business (even though the vast majority fail) or working to develop new medicines (which take many years and usually don’t pan out). Ironically overoptimism often tends to work out well for society (new restaurants, cures for disease) while endangering the individuals who take them (financial ruin, stress-induced insanity). Sadly we are often overoptimistic – my most recent example of this was just a few hours ago when I sat down to write an essay entitled: “The 7 Habits Of Highly Ineffective People.” If I only didn’t go out last night…..

Irrationally yours

Dan

Sunday Book Review

From the NYT Sunday Book Review:

STUFF YOUR BRAIN SAYS: “The Upside of Irrationality,” Dan Ariely’s follow-up to his 2008 best seller “Predictably Irrational,” hits the hardcover list at No. 12 this week. Ariely, a professor at Duke, is a leading researcher in behavioral economics. One of the field’s concerns is the way we tend to misjudge future pleasure — for example, by imagining that a new Ferrari will make us feel much happier than it actually does. But making The New York Times best-seller list, it turns out, really does feel good. “When my first book reached the list, I called my wife to tell her and I was just not able to talk from excitement,” Ariely said by telephone. “This was very interesting to me because I was very happy to hear the news, but somehow sharing it with someone I love intensified it to an extent that was just too much for me, and I was just able to say a word here and there and almost cry in between.” The differences in our experience of emotions when we are alone versus with others, he added, might be a fruitful avenue for future research.

So — how did I feel this time? About the same as the first time….

Irrationally yours

Dan

A Fun New iPhone app: At a boy!

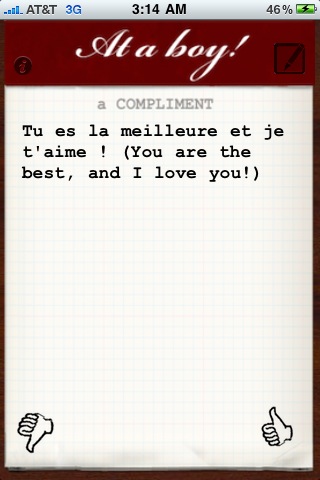

A few months ago, I had the idea to create an iPhone app that would give me (us) compliments. It turns out that as humans, not only are we sensitive to rude remarks from strangers, but we are also very excited when we get kind words, even if they are just random; they just make us feel much better, even if these strangers don’t know us very well.

At a boy! is a completely free app, and you can find it here.

HOW TO USE: when you open the app you get a compliment and if you want a new one simply tap the screen. To get a new compliment, simply tap the screen. I do want to encourage you to use the thumbs up/down to let me know which compliments make you feel the best — this way we will be able to figure out what kinds of compliments work better and worse.

Most important, users of At a boy! can submit their own compliments for other users to read: just tap the pen icon and type one in.

Here, for example, is a compliment that a French-speaking user of our app submitted (if you can please submit compliments also in English):

Doesn’t that make you feel good to read? We’ve had a few dozen great compliments already submitted, and we could always use more!

By the way, did I tell you that you look very nice today and that you are very clever?

Irrationally yours

Dan

NYT review of “The Upside”

The New York Times Sunday Book Review, just published a review of the Upside of Irrationality.

In general I think that the review is very good, but there is one point that made me wonder (and of course I focused on the one point that was less positive in the review).

One of the main differences between “The Upside” and PI is that this time around I wrote in a much more personal way about some of my experiences and how they got me thinking differently about different aspects of life (dating, adaptation, pain etc). It was very hard to write this way, and while writing I kept on wondering if this is a good approach to write or not. The reviewer from the NYT reaction was that I was overly personal in my descriptions, and maybe she was correct…

Either way it would be nice to find out the reaction to this approach — is writing in a more personal way, useful or distracting? I would love to get any feedback on this.

Thanks

Irrationally yours

Dan

How to commit the perfect crime

There is a certain perverse pleasure in contemplating the perfect crime.

You can apply your ingenuity to the hypothetical issues of choosing a target, evading surveillance and law enforcement, dealing with contingencies and covering your tracks afterward. You can prove to yourself what an accomplished criminal mastermind you would be, if you so chose.

The perfect crime usually takes the form of a bank robbery in which the criminals cleverly bypass all security systems using neat gadgets, rappelling wires and knowledge they’ve acquired over several weeks of casing the joint. This seems to be an ideal crime because we can applaud the criminals’ cunning, intelligence and resourcefulness.

But it’s not quite perfect. After all, contingencies by definition depend on chance, and therefore can’t ever be perfectly thought out (and in all good bank-robber movies, the thieves either almost get caught or do). Even if the chances of being caught are close to zero, do we really want to call this a perfect crime? The authorities are likely to take it very seriously, and respond accordingly with harsh punishment. In this light, the 0.001 percent chance of getting caught might not seem like a lot, but if you take into account the severity of punishment, such crimes suddenly seem much less perfect.

In my mind, the perfect crime is one that not only yields more money, but is one where, if by some small chance you did get caught, no one would care, and the punishment would be negligible.

So, with this new knowledge how would you go about it?

First, the crime would need to be obscure and confusing, making it difficult to detect. Breaking a window and stealing jewelry is too straightforward. Second, the crime should involve many people engaging in the same type of crime so that no one can point a finger at you. This is why looting, though easy to detect, is much more difficult to get a handle on than a single robbery. Third, your crime will need to fall under the shady umbrella of plausible deniability so that if you do get caught, you can always say you didn’t know it was wrong in the first place. With this kind of defense, even if the public cares, the legal system may let you off easy. Moreover, plausible deniability allows you to apologize in the aftermath and ask forgiveness for your “mistake.”

If you really want to go all out, do something you can spin in a positive light, and maybe even create an ideology around it. This way you can then explain how you’re actually on the side of progress. Say, for instance, you’re “providing liquidity” and “lubricating the market” and thereby helping the economy – even if it happens to be by taking people’s money. You can also resort to opaque and promising-sounding language to make your case; you’re “restoring equilibrium,” “eliminating arbitrage” and creating “opportunity” and “efficiency” across the board.

Basically, just bottle snake oil and tell them it will cure, rather than cause, blindness.

Something to avoid, on the other hand, is anything involving an identifiable victim with whom people can sympathize and feel sorry for. Don’t rob one little old lady blind, or any one individual for that matter. It’s part of human nature that we care so much about blue-collar crime, even though the average burglary only costs about $1,300 (according to 2004 FBI crime reports), of which the criminal only nets a few hundred. Crimes like burglaries are the least ideal crime: they’re simple, detectable, perpetrated by a single or just a few people. They create an obvious victim and can’t be cloaked in rhetoric. Instead, what you should aim for is to steal a little bit of money from as many people as possible—little, old or otherwise — it doesn’t matter, as long as you don’t reverse the fortune of any one individual. After all, when lots of individuals suffer just a bit, people won’t mind as much.

So, what is the ideal crime? Which activity is difficult to detect, involves many people, has plausible deniability, can be supported by an ideology and affects many people just a bit? Yes, I think you know the answer, and it does involve banks…

Seriously, what we have here is a problem with our priorities. We have tremendous regulations for what is legal and illegal in the domain of possessions and blue-collar crime. But, what about regulations in banking? It is not that I really think that bankers plan and plot crimes for a living (I don’t), but I do think they are continuously faced with tremendous conflicts of interests, and as a consequence they see reality in a way that fits their own wallets and not their clients. The recent turmoil in the market is just a symptom of this conflict of interest problem, and unless we remove conflicts of interests from the banking system, we are going to be part of a long stream of perfect crimes.

This blog post first appeared on a website for a new PBS show called Need To Know

The Upside of Irrationality is out…

This is an exciting day (but also a bit nerve-racking).

After a lot of hard work, “The Upside of Irrationality” is finally out, and now all I can do is to stand by and see how people react to it. The Upside of Irrationality covers different topics from Predictably Irrational, but it is also much more personal (hence the nerve-racking part).

Here is a short intro to this book, and if you end up reading it, let me know what you think:

I am going to be on a book tour for a few weeks, and here is a list of places that I will give talks at:

NEW YORK

TUESDAY, JUNE 1; 7:00 pm

B&N

2289 Broadway at 82nd Street

SAN FRANCISCO

THURSDAY, JUNE 3, 7:30PM

Berkeley Arts & Letters

Hillside Club

2286 Cedar Street

Berkeley CA 94709

MONDAY JUNE 7, 7:30PM

The Booksmith

1644 Haight Street

San Francisco CA 94117

SEATTLE

TUESDAY JUNE 8, 7:30PM

Town Hall Seattle

1119 8th Avenue

Seattle, WA

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 9, Noon

Chamber of Commerce lunch

Rainier Square Conference Center

5th and University

BOSTON

THURSDAY, JUNE 10, 6:00PM

Brattle Theater

40 Brattle Street

Cambridge

WASHINGTON, D.C.

SATURDAY, JUNE 12, 3:30PM

Politics & Prose

5015 Connecticut Avenue NW

ST. LOUIS

MONDAY, JUNE 14, 7:00PM

St. Louis County Library

1640 S. Lindbergh Blvd.

CHARLOTTE NC

TUESDAY, JUNE 15, 7:00PM

Joseph Beth Booksellers

4345 Barclay Downs Dr.

DURHAM NC

MONDAY, JULY 19, 7:00PM

Regulator Bookstore

720 9th Street

Durham, NC

A Focus on Marketing Research

When businesses want to find answers to questions in marketing, whom do they ask? Do they set up experiments to test their ideas, pitting the approach they think is most effective against alternatives? Do they survey consumers on a large scale? Do they go to experts who have questioned and requestioned their theories? Surprisingly, the answer is no. Most often, businesses rely on small “focus groups” to answer big questions. They rely on the intuition of about 10-12 lay people with no relevant training who ultimately have no idea what they’re talking about.

I wonder how can this be a useful strategy? Why ask those who are lacking any kind of proficiency when, by definition, experts are more knowledgeable on the topic and have experience that could actually be beneficial? And even if experts are more narrowly focused, and tunneled vision, how can this be better than carrying out their own research?

Research in psychology and behavioral economics has shown time after time that people have bad intuitions. We are very good at explaining our behavior (sometimes shocking and irrational), and to do so we create neatly packaged stories – stories that may be amusing or provocative, but often have little to do with the real causes of our behaviors. Our actions are often guided by the inner primitive parts of our brain – parts that we can’t consciously access — and because of that we don’t always know why we behave in the ways we do; still, we can compensate for this lack of information by writing our own versions. Our highly sophisticated prefrontal cortex (only recently developed, by evolutionary standards) takes the reigns and paints a perfect picture to explain what we don’t know. Why did you buy that brand of fabric softener? Of course, because you love the way it makes your clothes smell like a springtime breeze when you pull them out of the warm dryer.

So, why do businesses go to our imagination when we know it’s just a cover for what’s really going on? Indeed, why do businesses go to the imaginations of a group of people to find real answers? I suspect that the story here is linked to another one of our irrationalities: As human beings, we have an insatiable need for a story. We love a vivid picture, a penetrating example, an anecdote that will stay in our memories. Nothing beats the feeling of knowledge we get from a personal story because stories make us feel connected – they help us relate. Just one example of customer satisfaction has a stronger emotional impact than a statistic telling us that 87% of customers prefer product A over product B. A single example feels real, where numbers are cold and sterile. Although statistics about how a large group of people actually behave can tell us so much more than the intuitions of a focus group, the allure of a story is irresistible. Our inherent bias to prefer the story compels us to believe in the worth of small numbers, even when we know we shouldn’t.

This “focus group bias” is not just a waste of money it is also most likely a waste of resources when products are designed according to the “information” gathered from these focus groups. We need to find a way to base our judgments and decisions on real facts and data even if it seems lifeless on its own. Maybe we should try and supplement the numbers with a story to quench our thirst for an anecdote, but what we can’t do is forget about the facts in favor of fairy tales. In the end, the truth lies in empirical research.

—

Arming the Donkeys is back…

After a short break, my podcast (Arming the Donkeys) is back..

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like