Ask Ariely: On Favorite Flicks, Cosmetic Complications, and Expert Exchanges

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My friends and I are huge fans of action movies, and before the pandemic we used to gather once a month at someone’s house to watch a film. We’ve tried to keep the tradition going by picking a movie for everyone to watch on their own schedule and then getting together on a video chat to talk about it. I enjoy the discussions, but why don’t I seem to like watching the movies as much anymore?

—Jack

Research has shown that when people do something together, shared emotions are amplified, making the activity feel more intense and engaging. That’s especially true if there’s an exciting or emotional component to the activity, as with an action movie. To bring back some of the experience you’re missing, try organizing a watch-party where everyone streams the movie at the same time. Knowing you’re part of a group experience, even in virtual form, can bring back some of the excitement until you can start meeting in person again.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Earlier this year my brother decided to have cosmetic surgery. He understood that there was some risk involved, although it was low. Unfortunately, there were complications during the surgery and he ended up even more dissatisfied with his appearance than before. Now he’s considering a second surgery to correct the first one, but he’s worried that he’s making the same mistake twice. Do you think he should go ahead?

—Lee

Learning from past decisions is important, but it’s tricky to be sure we’re learning the right thing. In your brother’s case, the fact that his decision to have surgery led to unfavorable results doesn’t necessarily mean the decision was wrong. It’s easy to be swayed by “outcome bias”—using our knowledge of how a decision turned out to judge whether it was right in the first place. Based on the available information at the time, having the surgery could have been the right decision even if it turned out badly.

Likewise, your brother has to decide about a second surgery based on the information that’s available now, not knowing what the future will bring. My advice is for him to talk to his surgeon and learn everything he can about the probability of new complications. He should only go forward with the surgery if he’s willing to live with that risk, knowing that it can be reduced but not eliminated.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My family did a Secret Santa gift exchange this year, and I was assigned my sister’s new boyfriend, whom I hardly know. I ended up getting him a book, but I have no idea whether he liked it. What’s the best way to buy a gift for someone you don’t know well?

—Allison

Rather than trying to figure out what the recipient likes and risk getting it wrong, why not give them an experience they’ve never had before, like trying a new kind of cuisine? That way, even if they end up not loving the gift, at least they will have something new and unexpected to look forward to.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Overwhelming Options, Better Budgets, and Expensive Emotions

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

I offered to purchase a computer as a gift for a close relative, and I asked him to pick out the one he wanted. But he simply can’t make a choice. He keeps comparing different models and researching all the available features, even though I’m sure he will never use most of them. How can I help him to make a decision?

—Stanley

Choice paralysis, or what’s sometimes called “paralysis by analysis,” is a common problem. Some famous experiments in behavioral science have shown that making decisions is harder when you have too many options and too much information. To force your relative to limit his search, tell him that the two of you will sit down together and go shopping online for two hours; then you’ll buy the best computer you’ve found in that time. Using firm deadlines is a good way to combat our indecisive nature.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I use a budgeting app to set monthly spending goals for each category of expense, but every month I find that I’ve gone over my limit in multiple categories. Are budgeting apps just a waste of time?

—Anthony

The struggle that you are experiencing is not between you and your app but between your emotional self, which wants to get things now, and your cognitive self, which wants you to plan for a better future. My guess is that you’d be in an even worse situation without the app.

Budgeting isn’t effective if you set a spending goal and then don’t think about it again until the end of the month. Instead, try using the app to analyze your spending every other day. That way, when you find yourself spending too much, you’ll be able to adjust your behavior to stay on track for your monthly goal, rather than discovering you’ve overspent only when it’s too late to do anything about it.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Our daughter attends a very expensive private university, where I recently attended an event. There were lots of freebies for us to take, including fancy snacks and notebooks with the university logo. I was excited to get these items, but of course they aren’t really free since we pay so much in tuition.

I thought about this last week when my tennis team was playing a match at a different club, and we were asked to pay a $10 fee to use the facilities. This felt annoying and unfair, even though I spend a lot more than that on my tennis hobby overall. Why did I get so excited about those “free” items and so angry about this small expense, when neither of them really matters in the big picture?

—Juliet

The problem is that we tend to think about each of our expenses separately, rather than seeing them in their overall context. This is the source of many of our irrational financial decisions and emotions—whether it’s paying high fees to money managers who don’t justify the cost, or paying Amazon an annual fee for “free” shipping or getting annoyed when the supermarket starts charging a nickel for a plastic bag. It’s not easy to think clearly about each small expense in terms of our total financial situation, but if you can, you will be able to make better decisions about money.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Irrational Investments and Company Complaints

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

One of my credit cards bears the words “member since 1989.” The truth is that I haven’t used this card in years, even though I pay a $95 annual fee for it. But I can’t seem to bring myself to cancel it, simply because of that “member since 1989”! It feels like I would be giving up a status I’ve been building for 30 years. Why is it so hard for me to make what is clearly the rational financial decision?

—Arielle

You’re suffering from what economists call the “sunk cost fallacy.” To understand how this works, imagine you have spent 15 hours writing a new book, and you have 50 more hours to put in before you’re finished. Then you learn that someone else’s book on the exact same subject will be coming out next week. Should you keep working on your book for another 50 hours? Most people would say no—why spend so much time on a project that is unlikely to be successful?

But now imagine that instead of 15 hours, you have invested 1,500 hours in writing your book. In that case, would you put in another 50 hours to get it done? Now most people would say yes—if you’ve already spent 1,500 hours on something, why not put in the last 50 to finish it?

In both cases you are being asked to make the same amount of effort for the same doubtful result. But when you’ve invested a lot of time—or a lot of money—it’s hard to make the rational decision to write off your sunk cost and shift your resources to something better.

You’re facing a similar problem when it comes to your credit card. To make the decision clearer, ask yourself if you would keep paying for the card if it only said “member since 2019.” If your answer is yes, then keep it; if the answer is no, it’s clear that you are a victim of the sunk cost fallacy and you should cancel the card now, before that cost gets even bigger.

___________________________________________________

Hi Dan,

At least once a day, someone in my office sends an email to the whole company complaining about some small issue: Someone took the wrong lunch from the refrigerator, or someone drank the last of the coffee and didn’t make a new pot. I find it really annoying. Is there a way to get people to complain less?

—George

It seems like it should be simple to convince people to be more patient and polite. But the truth is that it’s much easier to change your own attitude than it is to change the behavior of your co-workers. One approach would be to make a game out of it: Every Monday, make a prediction about how many of these complaints will come your way that week. If your prediction is correct, reward yourself with some small indulgence. That way, you can think about the complaints not just as annoyances but as a way to earn a reward.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Ask Ariely: On Soiled Sinks, Busy Bathrooms, and Dainty Donations

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

People in my office drink a lot of coffee, which means a lot of mugs pile up in the sink. What happens is that one person leaves a dirty mug, and the next person to use the kitchen doesn’t want to clean that mug along with their own, so they leave theirs in the sink as well. Soon the sink is overflowing with these dirty dishes, and no one wants to take the time to wash all of them. If everyone just washed their own mug there wouldn’t be a problem, but what can we do to enforce this rule?

—Oran

As you observed, the heart of the problem is the first mug: If someone observes a dirty dish in the sink, they are less likely to wash their own, and so the problem is compounded over time. In my lab at Duke University we had the same issue, and we tried two different solutions. First, I put a picture of myself above the sink, looking directly into peoples’ eyes, with the message “Please don’t leave your dish in the sink.” This was meant to remind people of the importance of the rule, but while it helped a little, it didn’t eliminate the problem. Our next step was to issue everyone in the office a mug with their name written on it, so that it would be obvious who was responsible for leaving a dirty mug in the sink. The threat of being publicly embarrassed managed to solve the problem almost completely.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When I’m using the urinal in a public bathroom, it seems to me that I finish much faster when I’m alone than when someone is standing at the urinal next to me. Do you think this is a real phenomenon, or does it just feel that way because I’m more self-conscious when someone else is nearby?

—Joe

I once conducted an experiment on this subject on the MIT campus, in which a research assistant would enter a public men’s room alongside unsuspecting students. Sometimes he would use a urinal right next to a student, while other times he would leave a free urinal between them. We found that when men have someone using the urinal next to them, it takes them longer to start urinating, but once they start they finish faster, as if they’re trying to get it over with and leave quickly. So you’re not imagining it: Being observed in the bathroom does make the experience more stressful.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Recently I’ve been bombarded with requests for donations from various charities and political groups. Is it better to donate larger amounts of money to a few causes or smaller amounts to many?

—Barbara

There are many ways to define “better,” but if you’re asking what’s better for you personally, I would recommend making smaller, more frequent donations. Every time we help others, even a small amount, we get a boost of positive emotion, so you would enjoy this benefit more often. And because it’s psychologically harder to part with large amounts of money, you will enjoy making small donations more, which means you’re more likely to make giving into a habit.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

The (un-)expected link between the human and the artificial mind

Understanding the human mind is key to the better design of artificial minds.

A short report based on a paper by Darius-Aurel Frank, Polymeros Chrysochou, Panagiotis Mitkidis, and Dan Ariely

Technology around us is becoming smarter. Much smarter. And with this increased smartness come a lot of benefits for individuals and society. Specifically, smarter technology means that we can let technology make better decisions for us and let us enjoy the outcome of good decisions without having to make the effort. All of this sounds amazing – better decisions with less effort. However, one of the challenges is that decisions sometimes include moral tradeoffs and, in these cases, we have to ask ourselves if we are willing to allocate these moral decisions to a non-human system.

One of the clearest cases for such moral decisions involves autonomous vehicles. Autonomous vehicles have to make decisions about what lane to drive in or who to give way at a busy intersection. But they also have to make much more morally complex decisions – such as choosing whether to disregard traffic regulations when asked to rush to the hospital or to select whose safety to prioritize in the event of an inevitable car accident. With these questions in mind it is clear that assigning the ability to make decisions for us is not that easy and that it requires that we have a good model of our own morality, if we want autonomous vehicles to make decisions for us.

This brings us to the main question of this paper: how should we design artificial minds in terms of their underlying ethical principles? What guiding principle should we use for these artificial machines? For example, should the principals guiding these machines be to protect their owners above others? Or should they view all living creatures as equals? Which autonomous vehicles would you like to have and which autonomous vehicles would you like your neighbor to have?

To start examining these kinds of questions, we followed an experimental approach and mapped the decisions of many to uncover the common denominators and potential biases of the human minds. In our experiments, we followed the Moral Machine project and used a variant of the classical trolley dilemma – a thought experiment, in which people are asked to choose between undesirable outcomes under different framing. In our dilemmas, decision-makers were asked to choose who should an autonomous vehicle sacrifice in the case of an inevitable accident: the passengers of the vehicle or pedestrians in the street. The results are published under open-access license and are available for everyone to read for free at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-49411-7.

In short, what we find are two biases that influence whether people prefer that the autonomous vehicle sacrifices the pedestrians or the passengers. The first bias is related to the speed with which the moral decision was made. We find that quick, intuitive moral decisions favor killing the passengers – regardless of the specific composition of the dilemma. While in deliberate, thoughtful decisions, people tend to prefer sacrificing the pedestrians more often. The second bias is related to the initial perspective of the person making the judgment. Those who started by caring more about the passengers in the dilemma ended up sacrificing the pedestrians more often, and vice versa. Interestingly overall and across conditions people prefer to save the passengers over the pedestrians.

What we take away from these experiments, and the Moral Machine, is that we have some decisions to make. Do we want our autonomous vehicles to reflect our own morality, biases and all or do we want their moral outlook to be like that of Data from Star Track? And if we want these machines to mimic our own morality, do we want that to be the morality as it is expressed in our immediate gut feelings or the ones that show up after we have considered a moral dilemma for a while?

These questions might seem like academic philosophical debates that almost no one should really care about, but the speed in which autonomous vehicles are approaching suggests that these questions are both important and urgent for designing our joint future with technology.

How Does Pocket Ariely Make Sense of Life?

Check it out at: http://danariely.com/pocket-ariely/

Have you ever been in a situation where you could really use my help? How about putting away that last cupcake? Or saving that extra dollar for retirement? Maybe getting things done at work without draining all your time and energy? Or, maybe, you just need to spend less time giving out likes and more time nourishing your brain with food for thought?

I know I’ve felt that way, and chances are… so have you.

I want to introduce you to Pocket Ariely, a digital library of my most relevant work in behavioral economics and the best cheat sheet to life’s most difficult issues in Finance, Health, Productivity, Morality, Romance, and so much more. With Pocket Ariely, you can access videos, podcasts, articles, and even games that will prepare you to make sense of life through social science insights.

What’s more, all profits from Pocket Ariely will be put toward the research being conducted at my lab, the Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University. With your help, we will continue to advance the blossoming field of behavioral economics and continue the process of showing the world how irrational humans can be (sometimes), and ways to fix it.

The app is not free, but think about the monthly (weekly? daily?) $5 you spend on a Venti Caramel Macchiato at Starbucks, and skip one every other month in the name of science (your waistline will thank you too!). I promise you that we will keep working hard on some of humanity’s most pressing issues all for the cost of the occasional cup of Joe. Not a bad deal huh?

Download Pocket Ariely now

from the App Store and Google Play Store.

Irrationally yours,

Dan

Beginning at the End

Part of the CAH Startup Lab Experimenting in Business Series

By Rachael Meleney and Aline Holzwarth

Missteps in business are costly—they drain time, energy, and money. Of course, business leaders never start a project with the intention to fail—whether it’s implementing a new program, launching a new technology, or trying a new marketing campaign. Yet, new ventures are at risk of floundering if not properly approached—that is, making evidence-based decisions rather than relying on intuition.

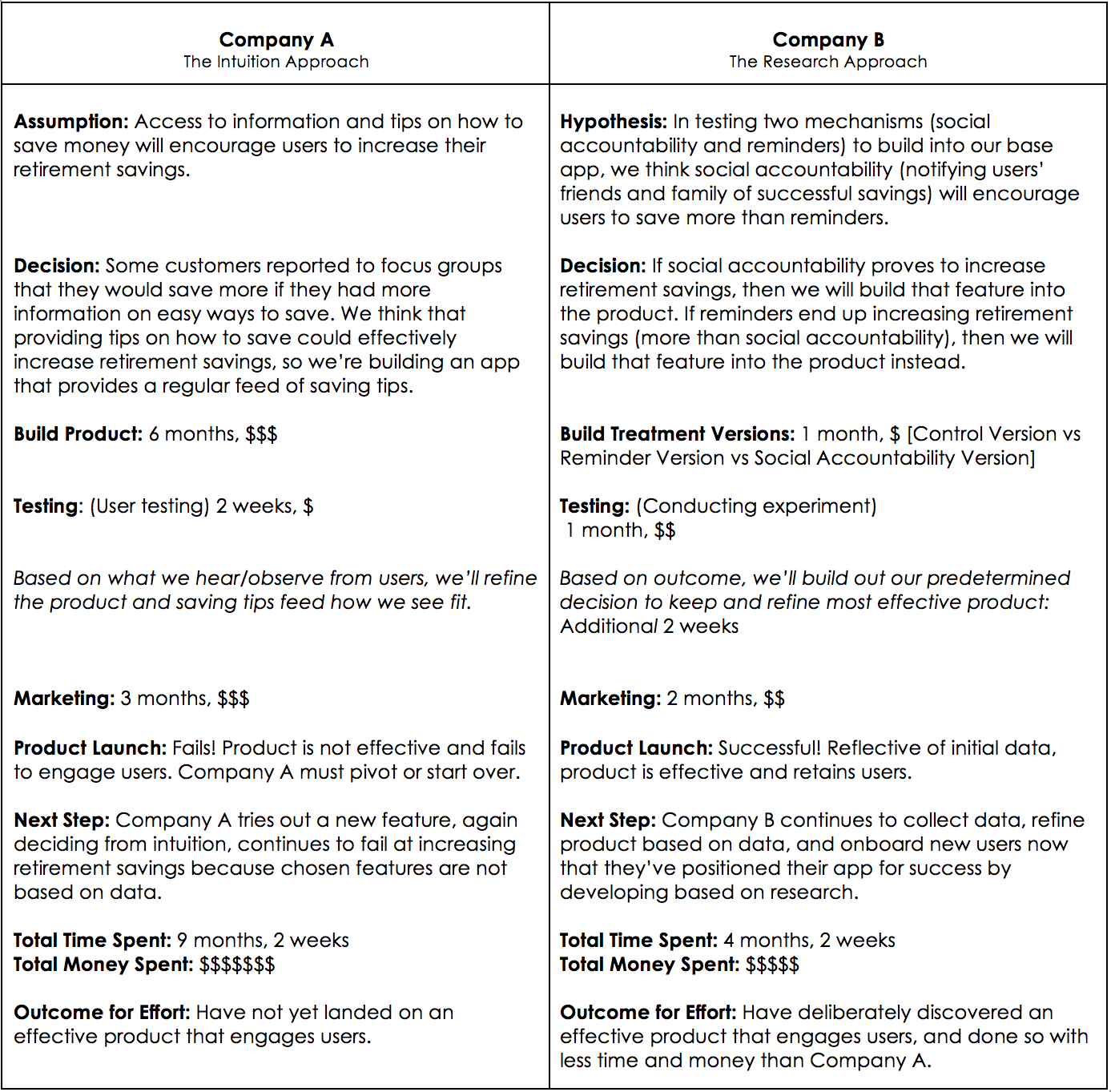

Let’s say your company is in the business of connecting consumers to savings accounts, helping them save for retirement through your app. You need to decide how your product will achieve this. Let’s look at how an intuition-backed approach (Company A) compares to a research-backed approach (Company B) in this scenario:

What if there was a way to more reliably ensure that business risks weren’t as prone to failure? As we see in the example above, the solution lies in well-planned experimentation.

If businesses can learn to identify concrete decisions needed to move new or existing projects forward, and set up experiments that directly inform those decisions, then much of the painful time, energy, and monetary costs of mistakes can be avoided. However, many business leaders and entrepreneurs are weary and unsure about how to leverage research to benefit their companies most effectively. Therefore, they rely (perhaps unknowingly) on riskier decision-making approaches.

As social scientists at Dan Ariely’s Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University, we’re in the business of human behavior and decision-making. We see in our research the effects that our biases and environments have on our ability to make optimal decisions. In the high-risk environment of building a company, founders aren’t well-served by calling shots based on gut feelings or reasoning plagued by cognitive biases. (Don’t feel bad! We’re only human!)

The better route? Rigorous experimentation. Asking well-formed research questions, designing tests with isolated variables and control groups, randomizing users to groups, and using data to inform business decisions.

Adapting the Process: Making Experimental Results Actionable

At the Center for Advanced Hindsight’s Startup Lab (our academic incubator for health and finance technologies), our mission is to equip startups with the tools to make business decisions firmly grounded in research.

But the research process has to be more accessible to businesses. Entrepreneurs often come to us excited about research, but with little to no idea of what it takes to execute a rigorous experiment. There’s a lot of anguish, confusion, and hesitation about where to even begin.

The Startup Lab makes experimentation more approachable to entrepreneurs who have the will, but often not the time and resources to run studies like our colleagues in academia.

There are specific considerations that businesses take into account when wading into the world of research. An important one is what makes investing in experimentation worthwhile? The driving purpose of running experiments, in most business contexts, is to uncover results that are clearly actionable.

So how do you ensure actionable results? You set up your process with this goal in mind from the start – not as an afterthought. The Startup Lab adapts Alan R. Andreasen’s concept of “backward market research”[1] to bring the process of planning and executing a research project to entrepreneurs.

The ‘Backward’ Approach: Beginning at the End

“Beginning at the end” means that you determine what decision you’ll make when you know the results of your research, first, and let that dictate what data you need to collect and what your results need to look like in order to make that decision.

This ‘backward’ planning is not how businesses usually approach research projects. The typical approach to research is to start with a problem. In business, this often leads to identifying a lot of vague unknowns—a “broad area of ignorance” as Andreasen calls it—and leaves a loosely defined goal of simply reducing ignorance. For example, startups often come to us with the goal of better understanding their customers. While we commend this noble goal, we ask, “to what end?”

What business decision will you make based on what your research uncovers?

The problem with the simple exploratory approach is that it sets you up for certain failure from the start. An unclear question produces an unclear answer. You’ll end up with data that you can’t possibly base a concrete decision on.

Let’s revisit the example of Company A (the intuition-based entrepreneurs) and Company B (their ‘backward market research’ counterparts). If you approach product development based on intuition like Company A, then you may be tempted to ask your customers about the challenges they have saving, or their ideal income at retirement – but this would be misguided if you don’t first determine what you will do with this information. If you find that your customers have trouble saving, you might conclude that you need to give them more information about the benefits of saving for retirement. If you create and implement this content into your app only to discover that it is completely ineffective at increasing savings, will you trash your product and start over? (Probably not. But if you set up your research in this way, then that may be the only logical conclusion.)

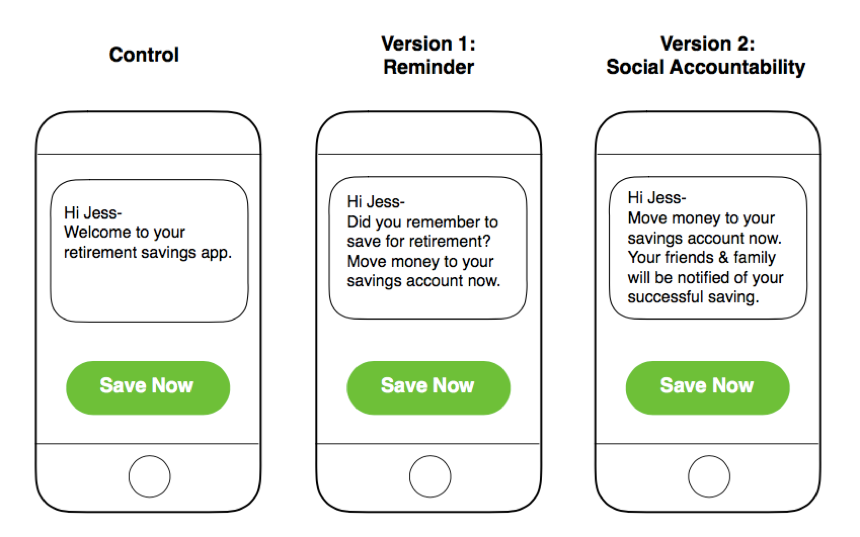

But imagine that instead, like Company B, you plan a research project to collect data on your users’ saving behavior (instead of probing to reduce your ignorance on their stated savings challenges). You set up an experiment to test two different ways of encouraging users to save (your two treatment groups, reminders and social accountability) against the current version of your product (what we call a control group).

Now you’ve set up an experiment, but you can’t stop at designing your research.

The “backward market research” approach forces you to specify which decisions you will make based on the outcome.

If the social accountability version leads your users to save twice as much as they do when using your base product, will you implement this mechanism in your product strategy? How will you do so, and what might the implications be? Once you determine 1.) The decision you will make from every possible outcome of your research results and 2.) How each decision will be implemented, then your research is set up to lead to actionable insights that have the power to move your business forward.

P.S. You too can design and conduct experiments using the ‘backward market research’ method. Use our handy tool to guide you through the backward approach: ‘Beginning at the End’ Worksheet.

And remember, to orient your research toward actionable decisions, start with the end in mind.

[1] Andreasen, A. R. (1985). ‘Backward’Market Research. Harvard Business Review, 63(3), 176-182.

At the Center for Advanced Hindsight’s Startup Lab, our academic incubator for health and finance tech solutions, we aim to instill a commitment to research-backed business decisions in the companies we bring into our fold. We will be releasing more articles and tools like this as part of our Experimenting in Business Series on our blog. Leveraging research for smart business decisions is a powerful skill—we’re aiming to make rigorous experimenting less intimidating and more accessible to a broad range of businesses.

By the way—we’re also accepting applications for the Startup Lab’s upcoming program, which starts in October. We’re looking for startups that are eager to experiment, and demonstrate a passion for building research-backed solutions to health and finance challenges.

APPLY NOW.

You only have until June 30th at 5pm EST.

Build better health and finance tech products for humans. Join the Startup Lab.

We’re excited to announce that we’re searching for our next class of the Startup Lab, which begins October 2017. Applications are only open until June 30th at 5pm EST.

Apply to the Startup Lab now.

Our academic incubator supports problem-solvers by making behavioral economics findings accessible and applicable. See how behavioral researchers and entrepreneurs work together at the Center for Advanced Hindsight:

The Startup Lab provides:

- Ability to explore behavioral economics and learn how to leverage findings for your startup

- Opportunity to collaborate with world-renowned behavioral researchers

- Guidance and resources to run rigorous experiments

- Office space in downtown Durham, NC up to 9 months (October-June)

- Investment up to $60k

Are you insatiably curious about what drives decisions, shapes motivation, and influences behavior? Does your startup’s success hinge on the ability to affect positive behavior change that helps people live happier, healthier, and wealthier lives?

We’re looking for startups that are eager to experiment, and demonstrate a passion for building research-backed solutions to health and finance challenges.

APPLY NOW.

You only have until June 30th at 5pm EST.

To learn more, visit our FAQs (includes information on the Startup Lab investment structure and other logistics) or connect with us at startup@danariely.com.

Email Notifications

How many of our emails should we know about the moment someone decides to email us?

205 billion. That’s the number of emails we sent and received in 2015, and that number is expected to grow to 246 billion by 2019.[1] What does this mean for most of us? A steady stream of new messages coming into our inboxes throughout the day. And for most of us, it seems to be a norm to keep our inboxes open throughout the work day. We focus on the tasks we have at hand, and each “ping” from our inbox draws our attention, even if briefly, before we return back to our work.

The problem here is the high cost of interruption. This cost includes three categories: 1) time cost 2) performance cost 3) stress/ emotional well-being.

Time Cost In terms of time cost, researches have shown that any switching between tasks results in a loss of time. In other words, “multi-tasking” is a misnomer – we aren’t actually doing two tasks at once. We are doing one task, switching to the other, and then switching to the original task. One study showed that after switching tasks, it took an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds for people to get back to their original task.[2]

Performance Cost It should be no surprise to us that distraction can cause reductions in cognitive performance. In psychological terms, “task-irrelevant thoughts,” that is – thoughts that are unrelated to the task at hand, have indeed been shown to have deleterious effects on performance.[3]

A recent study published in The Journal of Experimental Psychology illustrates how this plays out for cell phones in particular, focusing on the distraction that cell phone notifications can create. In this study, participants were tasked with completing a task involving seeing items and pressing a button every time the item was a digit from 1-9, unless it was the number 3. Some were interrupted with notifications and others were not. The study found that the notification groups were more likely to make errors than the no-interruption group.

Stress/Emotional Well-Being A third factor to consider with interruptions is the effect they have on people’s well being. Task switching is fatiguing for us; it depletes us. One study showed that interruptions resulted in higher feelings of stress, pressure and effort.[4]

At this point, it should be painfully clear to us that we need to be worried about the interruptions-economy. What value interruptions provide, under what conditions, and what are their costs? A little ping may seem innocuous, but there is cumulating evidence that the cost of an interruption is higher than we realize, and of course given the sheer number of interruptions, their combined effect can very quickly become substantial.

If email interruptions can have all these negative effects, what can we do to reduce them? The first thing we should question is this idea that all emails are created equal. Should each email be able to interrupt people? Is the email from someone’s boss as important as the weekly industry newsletter he’s signed up for? What if we designed a different system in which emails were not treated equally?

In a previous study, we looked at how many emails truly are worthy of interruption. We asked people to look at the last 40 emails they received and asked them how soon they really needed to have seen each email. Immediately? At some point today? At some point this week? At some point this month? No need to see it at all?

As it turns out, very few – only 12%! – of emails need to be seen within 5 minutes of being sent.

7% of emails need to be seen within 1 hour, 4% within 4 hours, 17% by the end of the day, 10% by the end of the week, 15% at some point, and a whopping 34% fell into the “no need to see it” category.

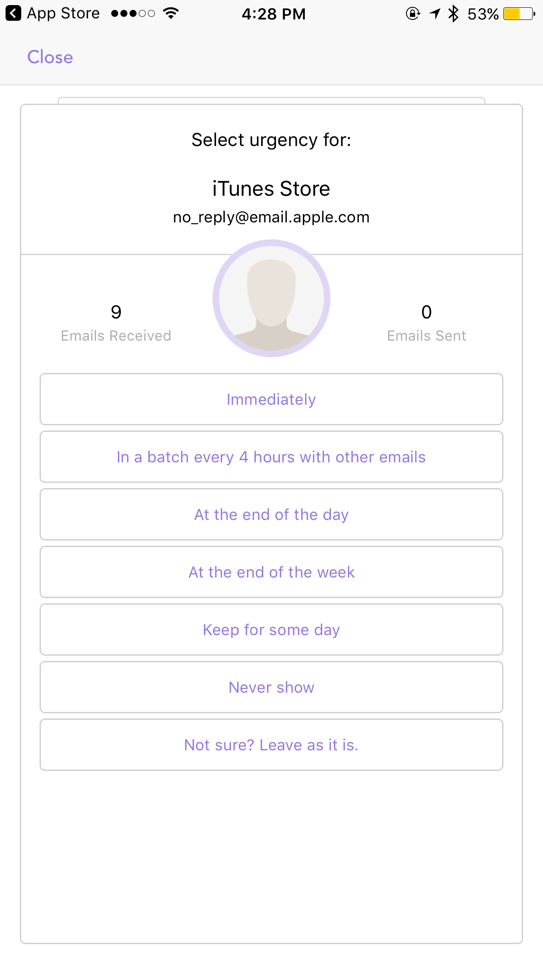

With that initial starting point – the idea that very few emails need to be seen right away – we set out to build a tool to allow people create rules for receiving emails. We used a very simple sorting technique: sorting emails based on the sender. In other words, depending on the sender, emails could be set to be received at different intervals. No complex AI or learning mechanisms.

Example of instructions users were given

Example of prompt to set rule by each sender

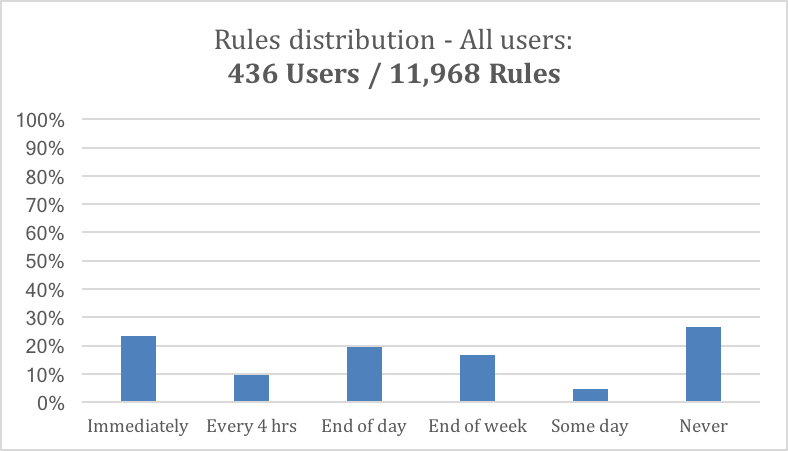

What did we find? People proceeded to create rules based on senders. Similar to our initial findings, only 23% of emails were set up to be in the “immediate” category. 10% were relegated to the every-4-hours category, 19% to the end of the day, 16% to the end of the week, 5% to some day and a whopping 27% to the “never” category.

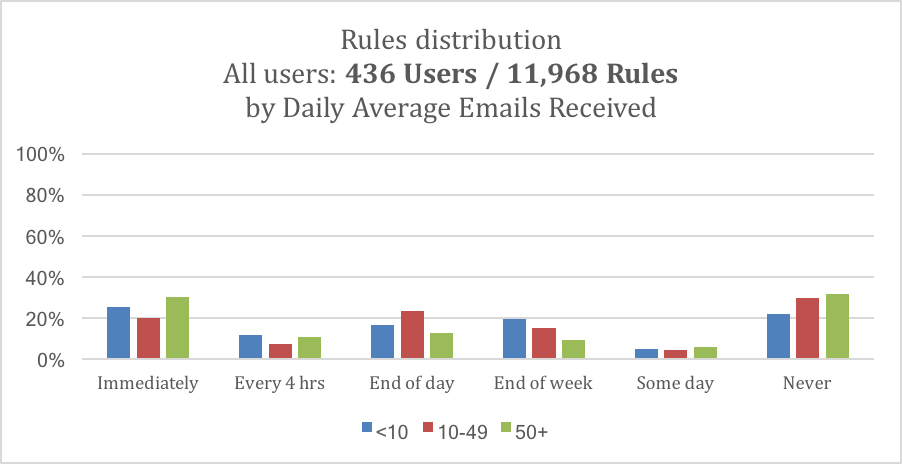

We also looked at whether people who received high vs, low quantities of emails behaved differently. While on the whole they had similar behavior, one interesting point of note is that people with 50+ emails/day put highest number of emails into “immediately bucket” (30%) vs. 10-49 emails/day (20%) and <10 emails/day (26%).

Overall, the key point and opportunity we should take away from all of this is that a very simple mechanism can have an impact, creating a significant amount of benefit for people. If you’d like to try this app for improving your email process for yourself, you can download it here.

[1] http://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Email-Statistics-Report-2015-2019-Executive-Summary.pdf

[2] Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Paper presented at the 107-110. doi:10.1145/1357054.1357072

[3] Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2006). The restless mind. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 946–958. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.946

[4] Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Paper presented at the 107-110. doi:10.1145/1357054.1357072

Higher Education, Higher Incomes…Opportunity for all?

Having a college degree can dramatically increase a young adult’s income. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2014 the median earnings of young adults (ages 25-34) with a bachelor’s degree were 66 percent higher ($49,900) than the median earnings of young adults with only high school diplomas ($30,000).

Anyone who performs well in high school can apply to college, and there are many scholarships, financial aid, and other support programs available to help make college an option for everyone. But does this help?

Topic 4 in Fair Game? asked users to think about whether household income is related to the likelihood of getting a college degree and what that relationship should look like in a fair world.

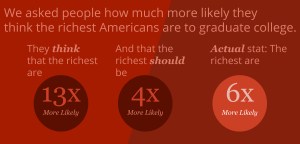

On the whole, our users estimated that the wealthiest 25% of society would be 13x more likely to get a college degree than the poorest 25%. In reality, the wealthiest 25% are about 6x more likely to get a college degree.*

How much more likely do people think the wealthy should be to get a college degree, in a fair world? 4x more likely.

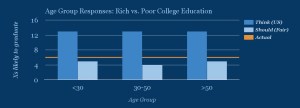

Estimates for the greater likelihood of getting a college degree were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair. There may be hints of a difference in what people think is fair, with 30-50 year-olds reporting 4x likelihood, while other age groups said a 5x likelihood would be fair. One possible explanation for this difference is that people in the 30-50 age range may be actively planning or paying for their children’s college expenses.

What about gender? Males and females differ in their estimates of the greater likelihood of getting a college degree for the top 25% of income, estimating 12 and 14 times greater likelihoods, respectively. But they agree in what they think a fair likelihood would be — 4x.

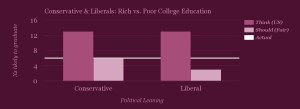

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal estimate the same (13x) greater likelihood of getting a college degree for the wealthy. In terms of how much more likely the top 25% of income should be to get a degree, in a fair society, conservatives answered 6x more likely and liberals answered 3x more likely. So although their understanding of the world is similar, their notions of fairness, for this topic, are very different.

Together, the data reported here suggest that people overestimate the gap in the likelihood of getting a college degree. And they would reduce the size of the gap that they perceive. There are many factors that contribute to the gaps in attainment of a college degree. Family income based factors are certainly an important contributor. But there are also decisions about whether to apply to college at all, what type of college to attend (e.g. for profit vs. nonprofit), how to access and pay back loans, and what kind of support a student may have from their social networks. Sometimes, just the paperwork involved in applying to college can overburden a prospective student and derail the process. It is encouraging then that low-cost interventions have the potential to improve college opportunities for low-income students.

Given the potential economic benefits that would result from more low-income students getting a degree, what are other possibilities that might work to increase the proportion who ultimately do get a degree?

What do you think? Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like