Ask Ariely: On Passionate Presents, Curious Compulsions, and Happiness Hints

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Before we got married four years ago, my husband and I would give each other amazing, thoughtful birthday gifts. After we got married and set up a joint bank account, our birthday presents stopped being exciting or original—and recently, they stopped altogether. Now we just buy things we need and call them gifts. Is this deterioration because of the shared bank account, or is it just the story of marriage?

—Nis

Some of it, of course, is how marriage changes us once we’ve settled down. But the shared bank account is also important here, and that part is simpler to change.

In giving a gift, our main motivation is to show that we know someone and care for them. When we use our own money to do this, we are making a sacrifice for the other’s benefit. When we use shared money, this most basic form of caring is eliminated. We are simply using common resources to buy the other person something for common use—which greatly mutes a gift’s capacity to communicate our caring.

The simplest step to restore some excitement to your gifts is to set up a small individual account for each of you for your own discretionary spending. The longer, harder discussion is how to get marriages to sustain passion longer.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently started investing in the stock market. I know that people who manage to outperform the market buy stocks and then don’t look at their performance for a very long time. But I can’t stop looking at my portfolio every couple of hours. How can I keep myself from peeking so often?

—Edwin

Curiosity is a powerful drive, and it can lead us to expend time and effort trying to find out things that we’re better off not knowing. Curiosity also can create a self-perpetuating feedback loop, which is what you are experiencing: You think about the value of your portfolio, you become curious, you get annoyed by not knowing the answer, and you check your investments to satisfy your curiosity. Doing this makes you think about your stocks even more, so you feel compelled to monitor them ever more frequently—and then you’re really caught.

The key to getting a handle on this habit is to eliminate your curiosity loop. You can start by trying to redirect your thinking: Every time your mind wanders to your portfolio, try to busy it with something else, like baseball or ice cream. Next, don’t let yourself immediately satisfy your curiosity. For the next six weeks, check your portfolio only at the end of the day—or, better, only on Friday, after the markets have closed.

All of this should let you train yourself to not be so curious—and not to act on the impulse as frequently. Over time, the curiosity loop will be broken.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Have you found any small tricks you can use to make yourself happier?

—Or

At some point, I managed to record my wife saying that I was correct. That doesn’t happen very often. I made this recording into a ringtone that plays whenever she calls my cellphone.

This not only made me happy when I was able to get the initial recording but also provides me with continuous happiness every time she calls.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Tempting Tomatoes, Genuine Gestures, and Optimistic Outcomes

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

We grow lots of tomatoes in our backyard garden, and we eat or freeze all of them. Each year, our neighbors hint about wanting some share of the bounty. We like our neighbors and occasionally socialize with them, but we fear that sharing our tomatoes will create an expectation for subsequent years. We also worry that such a gift would suggest the tomatoes are free when they actually cost us dearly in time and effort. Are we right, or are we just stingy tomato-hoarders?

—Martha

You’ve got a point. Just giving your neighbors the tomatoes that they covet will indeed encourage them to take for granted the work that goes into growing them. It will also create the expectation of future installments.

You could try to pre-empt the issue altogether by complaining demonstratively to your neighbors at the start of each growing season that you fear you won’t be able to grow enough to meet your own needs this year. But that would be dishonest.

Here’s a better approach: help your neighbors to experience firsthand the effort involved. This season, pick a weekend when you’ll be doing a lot of arduous garden work (maybe tilling the soil) and invite the folks next door to help out.

This will lessen your own workload and let them see how much sweat goes into gardening. You will then feel better about sharing some of the tomatoes that they will have helped to grow. Maybe your neighbors will learn to like gardening enough to start their own garden—and will share their own crops with you next year.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

When I pay someone a compliment, they often say something along the lines of “Thank you, but your house is beautiful too” or “Thank you, but your children are also so accomplished.” This makes me feel that my compliments aren’t being taken as genuine expressions of esteem but instead are seen as a sign of my own low self-esteem or an attempt to fish for accolades myself. I find that I’ve stopped complimenting people altogether. Should I?

—Irene

What’s happening here is best explained by the principle of reciprocity: When someone does something nice for us, we feel compelled to return the favor, often in a similar way. With compliments, the easiest way to reciprocate is to promptly return them.

This yearning for reciprocity is deeply rooted in our evolutionary history. It has long helped to strengthen social bonds. So when people quickly compliment you back, it isn’t a response just to you; it’s human nature. They don’t think you need the emotional boost, but they do feel the need to reciprocate.

The upshot? Don’t take this personally, let alone badly. Even more important, don’t stop giving compliments. Praise is free, and it makes people happier, so offer it to others whenever you can and enjoy it when it comes your way.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve heard that you just turned 50. Is there any good news about getting old?

—Ron

Yes: Our eyesight deteriorates. Everything turns out to look better slightly blurry and without details, particularly other people’s faces.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Ask Ariely: Helmet Hesitation, Contemporary Caring, and Bicycle Bummers

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A friend told me recently that wearing a bike helmet is actually more dangerous than not wearing one because those who wear a helmet take more risks, which outweighs the benefits of having their heads protected. Should I tell my kids to stop wearing helmets?

—Phil

Definitely not, but the question is a complex and interesting one. The real issues here are: what kinds of injuries helmets can prevent, how wearing a helmet alters our behavior and how our risk-taking changes over time.

Let’s think for a minute about a related case: seatbelts. When drivers, pushed by legislation, began to wear seatbelts as a matter of course, they might have felt extra-safe at first, making them think that they could get away with driving more aggressively. But after a while, as wearing a seatbelt became fairly automatic, that sensation of cocooning safety subsided. The tendency to take extra risks subsided too. So the full benefits of seatbelt use only emerged after we got used to wearing them all the time.

The same can be said about helmets. When we initially put one on, we may feel overconfident and cut more corners with road safety. But once helmet-wearing becomes a habit, we should revert to more prudent behavior, which will let us realize the helmet’s full benefits. That’s especially important, of course, with children.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m finding dating tricky these days. I’d like to show some chivalry, but it isn’t clear how to do that. Try as I might to pay the bill for dinner as a sign of respect and care, the women I’ve been out with seem to want to split it. Any advice?

—Ron

Acts of chivalry are acts of respect. They aren’t about practicality but about doing something kind for the other person. So I would suggest instead that you open the car door for your dates.

Decades ago, when car doors had to be unlocked manually, it was customary for the driver to open the door for the passenger. These days, when car locks release with a click and a beep from a keychain, doing so seems like a pointless gesture.

But that only makes it a stronger signal of chivalry: You don’t have to open your date’s door to let her in or out, but by choosing to do so, you offer a true act of consideration and caring. And it’s not only a nice gesture–it’s cheaper than picking up the tab.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why don’t people bike more? Bicycles are amazing vehicles—fast, efficient, easy to park, good for our health and our planet. What’s holding us back?

—Ziv

Simple: hills. Bicycles are fine things, and technology will no doubt continue to make them lighter, faster and safer. But all of these improvements aren’t likely to overcome our laziness—our deep-seated desire to move through the world with as little effort as possible.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Last post about the INT

After a month on the INT

Birthday Gifts

My 50th is getting closer and closer (April 29th) and because a few people have asked me over the past few days what I want for my birthday, I am walking while wondering about what makes a good gift. There are a few obvious ways to think about good gifts. Good gifts should be experiences and not things. Good gifts should be memorable. Good gifts should be unique. Good gifts should increase the social bond between the giver and the receiver. Good gifts are things that the receiver wants, but is not willing to buy for themselves. Good gifts are things that would make the receiver happy, but they don’t realize that it will.

But what are some good examples of good gifts? Headphones, Pens? Culinary classes? I would love to get examples of good gifts that you either gave or received.

And what gifts did I ask from my friends this year? I asked them not to give me anything, but I also told them that if they feel that they have to give me something, I want a copy of one of their favorite book, with an explanation why they love this book so much. And I am looking forward to having this shelf of books and reading it over the next few years.

Ask Ariely: On Cutting Cola, Loving Labor, and Engaging Investments

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been drinking soda for the past 15 years, and I’m trying to stop. I’ve tried phasing it out by switching to water some of the time and having a soda here and there, but I usually cave in to temptation by the end of the day. Is there a better strategy?

—Andrew

Getting off soda gradually isn’t going to be easy. Every time you resist having one, you expend some of your willpower. If you’re asking yourself whether you should have a soda whenever you’re thirsty, you’ll probably give in a lot and gulp one down.

So how can you break a habit without exposing yourself to so much temptation and depending on constant self-control to save you? Reuven Dar of Tel Aviv University and his colleagues did a clever study on this question in 2005. They compared the craving for cigarettes of Orthodox Jewish smokers on weekdays with their craving on the Sabbath, when religious law forbids them to start fires or smoke.

Intriguingly, their irritability and yearning for a smoke were lower on the Sabbath than during the week—seemingly because the demands of Sabbath observance were so ingrained that forgoing smoking felt meaningful. By contrast, not smoking on, say, Tuesday took much more willpower.

The lesson? Try making a concrete rule against drinking soda, and try to tie it to something you care deeply about—like your health or your family.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been living with a roommate for six months, and we divide up the household responsibilities pretty evenly, from paying the bills to grocery shopping. He says, however, that he feels taken for granted—that I don’t acknowledge his hard work. How can I fix this?

—C.J.

This is a pretty common problem. If you take married couples, put the spouses in separate rooms, and ask each of them what percentage of the total family work they do, the answers you get almost always add up to more than 100%.

This isn’t just because we overestimate our own efforts. It’s also because we don’t see the details of the work that the other person puts in. We tell ourselves, “I take out the trash, which is a complex task that requires expertise, finesse and an eye for detail. My spouse, on the other hand, just takes care of the bills, which is one relatively simple thing to do.”

The particulars of our own chores are clear to us, but we tend to view our partners’ labors only in terms of the outcomes. We discount their contributions because we understand them only superficially.

To deal with your roommate’s complaint, you could try changing roles from time to time to ensure that you both fully understand how much effort all the different chores entail. You also could try a simpler approach: Ask him to tell you more about everything he does for the household so that you can grasp all the components and better appreciate his work.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Is it useful to think about marriage as an investment?

—Aya

No, because the two things are profoundly different. You never want to fall in love with an investment because at some point you will want to get out of it. With a marriage, you hope never to get out of it and always to be in love.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On a Magnificent Milestone, Processing Pain, and Relentless Reflection

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I know that you’re turning 50 this year. How are you handling the big milestone?

—Abigail

As you can imagine, I was rather apprehensive about my 50th birthday, but I decided to embrace it and designed my year with some extra time to reflect.

In fact, I am writing to you from the sixth day of a 30-day hike along the Israel National Trail, which spans the country of my birth from Eilat to the Lebanese border. I wanted to disconnect from technology and have more time to think about what I want from life and want to do next. Six days in, checking email only late at night, I’m already in a more relaxed and contemplative mode.

I also designed the hike to help me think about earlier stages in my life. So for each day along the trail, I have invited family and old friends to join me to walk and reflect on the road behind. I’ve just finished a day of hiking with six friends from first grade, and talking about our joint history and deep friendships made me calmer than I could have imagined.

Sure, I’m a bit worried about aging. But so far, taking myself out of the usual hurly-burly and opening up space to reconnect with loved ones is proving to be an amazing antidote to the 50th blues.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

How do people recover from horrible injuries, psychological traumas and other life-altering events? Is it character or circumstances that dictate whether people crumble or rebound?

—Lionel

My sense, as someone who suffered very serious injuries as a teenager, is that the answer is both. Resilience is surely a function of one’s character and level of support, but it also has to do with the circumstances of the injury.

One of the most interesting lessons we have learned on this subject comes from Henry K. Beecher, the late physician and ethicist. In his 1956 study of pain in military veterans and civilians, Beecher showed how important it is to understand how people interpret the meaning of their injuries. These interpretations, he argued, can shape the way we experience trauma and pain.

Beecher found that veterans rated their pain less intensely than did civilians with comparable wounds. When 83% of civilians wanted to take a narcotic to manage their pain, he found, only 32% of veterans opted to do likewise.

These differences depended not on the severity of the wound but on how individuals experienced them. Veterans tended to wear injuries as a badge of honor and patriotism; civilians were more likely to see injuries just as unfortunate events that befell them. The more we interpret events as the outcome of something that we did, rather than something done to us, the better our attitude and recovery.

This lesson, while very important for traumatic injuries, also applies to the small bumps of daily life.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My relationship with my husband is going downhill, and I can’t stop thinking about it—which is putting an added strain on our marriage. What can I do?

—Rachel

Trying not to think about something is one of the best ways to ensure that you think about it constantly. If you try not to think about polar bears for the next 10 minutes, you will think more about them in those 10 minutes than you have in the past 10 years.

The same is true for your relationship with your husband. Instead of trying not to think about your marital woes, try reflecting on the good things in your relationship—then try to find activities together that will strengthen your bond. Good luck.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Hiking the Israel National Trail

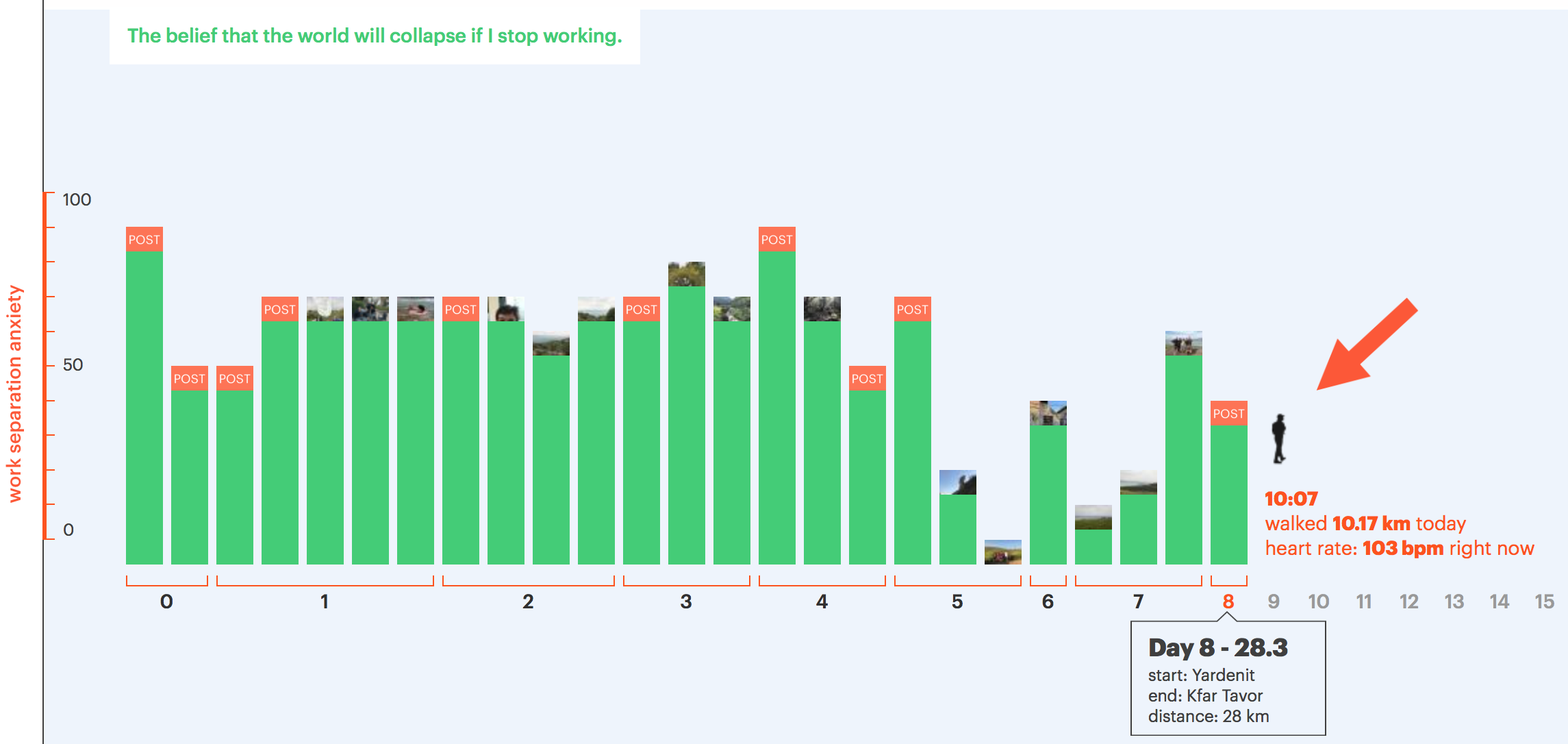

I’m just starting the second week of my month-long hike, and have been tracking some things along the way:

- Light Happiness

- Deep Happiness

- Love

- Optimism

- Regret

- Empathy

- Loving Nature

- Work Separation Anxiety

- Communication Anxiety

So far, I appear to be pretty stable on most dimensions (light happiness has taken a few dips but deep happiness is consistently high, and love/optimism/loving nature have remained high), but I’m most noticeably experiencing a downward trend on work separation anxiety. The more time I spend hiking, the less I am worrying about the growing list of tasks that would otherwise keep me up at night. It took a few days for me to get here, but my work is now taking a back seat to the importance of this trip.

I decided to embark on this adventure as an acknowledgement of my upcoming 50th birthday, and as an opportunity to reflect on life and how I want to spend the rest of it.

You can follow my journey at http://danarielyishikingtheint.com and see how the next few weeks pan out!

Irrationally Yours,

Dan Ariely

Ask Ariely: On Momentary Meaning, Hurried Health, and Poetic Practice

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why is it that the things that make me happy—such as watching basketball or going drinking—don’t give me a lasting feeling of contentment, while the things that feel deeply meaningful to me—such as my career or the book I’m writing—don’t give me much daily happiness? How should I divide my time between the things that make me happy and those that give me meaning?

—Vasini

Happiness comes in two varieties. The first is the simple type, when we get immediate pleasure from activities such as playing a sport, eating a good meal and so on. When you reflect on these things, you have no trouble telling yourself, “This was a good evening, and I’m happy.”

The second type of happiness is more complex and elusive. It comes from a feeling of fulfillment that might not be connected with daily happiness but is more lastingly gratifying. We experience it from such things as running a marathon, starting a new company, demonstrating for a righteous cause and so on.

Consider a marathon. An alien who arrived on Earth just in time to witness one might think, “These people are being tortured while everyone else watches. They must have done something terrible, and this is their punishment.” But we know better. Even if the individual moments of the race are painful, the overall experience can give people a more durable feeling of happiness, rooted in a sense of accomplishment, meaning and achievement.

The social psychologist Roy Baumeister and his colleagues distinguish between happiness and meaning. They see the first as satisfying our needs and wishes in the here-and-now, the latter as thinking beyond the present to express our deepest values and sense of self. Their research found, unsurprisingly, that pursuing meaning is often associated with increased stress and anxiety.

So be it. Simply pursuing the first type of happiness isn’t the way to live; we should aim to bring more of the second type of happiness into our lives, even if it won’t be as much fun every day.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently had my annual checkup, and my doctor spent maybe three minutes total with me during the visit. I know that physicians are busy, but are these quick visits the right way to go?

—James

Sadly, doctors increasingly feel pushed to move patients along as quickly as possible, like a production line. Research has shown that this approach hurts the doctor-patient relationship, which has important health implications.

Consider a 2014 study of patients who received electrical stimulation for chronic back pain, conducted by Jorge Fuentes of the University of Alberta and colleagues. They had medical professionals interact in one of two ways with their patients. Some were asked to keep their interactions short, while others were urged to ask deep questions, show empathy and speak supportively. Patients who received the rushed conversations reported higher levels of pain than those who got the deeper ones.

In other words, empathetic discussions are important for our health. Sadly, as physicians and other medical professionals become ever busier, we are shortchanging this vital part of healing.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Every year, my husband gets me a nice birthday card, but he never writes a personal note inside. Why?

—Ann

I suspect your husband overestimates the sentimental value of the words printed on the card, not realizing that they sound generic to you. Don’t judge him too harshly for this. Instead, buy one of those magnetic poetry sets and let him practice expressing himself on the fridge. Small steps.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like