Ask Ariely: On Passionate Presents, Curious Compulsions, and Happiness Hints

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Before we got married four years ago, my husband and I would give each other amazing, thoughtful birthday gifts. After we got married and set up a joint bank account, our birthday presents stopped being exciting or original—and recently, they stopped altogether. Now we just buy things we need and call them gifts. Is this deterioration because of the shared bank account, or is it just the story of marriage?

—Nis

Some of it, of course, is how marriage changes us once we’ve settled down. But the shared bank account is also important here, and that part is simpler to change.

In giving a gift, our main motivation is to show that we know someone and care for them. When we use our own money to do this, we are making a sacrifice for the other’s benefit. When we use shared money, this most basic form of caring is eliminated. We are simply using common resources to buy the other person something for common use—which greatly mutes a gift’s capacity to communicate our caring.

The simplest step to restore some excitement to your gifts is to set up a small individual account for each of you for your own discretionary spending. The longer, harder discussion is how to get marriages to sustain passion longer.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently started investing in the stock market. I know that people who manage to outperform the market buy stocks and then don’t look at their performance for a very long time. But I can’t stop looking at my portfolio every couple of hours. How can I keep myself from peeking so often?

—Edwin

Curiosity is a powerful drive, and it can lead us to expend time and effort trying to find out things that we’re better off not knowing. Curiosity also can create a self-perpetuating feedback loop, which is what you are experiencing: You think about the value of your portfolio, you become curious, you get annoyed by not knowing the answer, and you check your investments to satisfy your curiosity. Doing this makes you think about your stocks even more, so you feel compelled to monitor them ever more frequently—and then you’re really caught.

The key to getting a handle on this habit is to eliminate your curiosity loop. You can start by trying to redirect your thinking: Every time your mind wanders to your portfolio, try to busy it with something else, like baseball or ice cream. Next, don’t let yourself immediately satisfy your curiosity. For the next six weeks, check your portfolio only at the end of the day—or, better, only on Friday, after the markets have closed.

All of this should let you train yourself to not be so curious—and not to act on the impulse as frequently. Over time, the curiosity loop will be broken.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Have you found any small tricks you can use to make yourself happier?

—Or

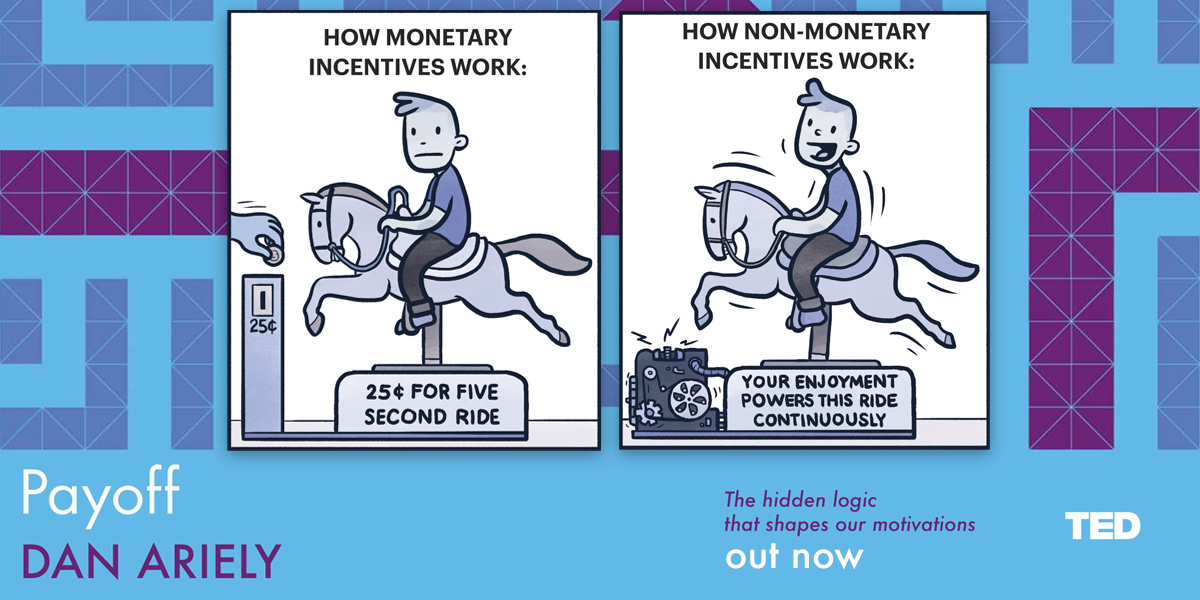

At some point, I managed to record my wife saying that I was correct. That doesn’t happen very often. I made this recording into a ringtone that plays whenever she calls my cellphone.

This not only made me happy when I was able to get the initial recording but also provides me with continuous happiness every time she calls.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Life (and the Pursuit of Happiness)– But for How Long?

Confronting our mortality is not an easy task for most people. However, there are many reasons people should consider just how long they might live.

In the case of retirement planning, life expectancy is important in relation to the benefits like Medicare and Social Security that people earn during their working years. According to the Pew Research Center, use of these government benefits programs is “virtually universal (97%) among those ages 65 and older—the age at which most adults qualify for Social Security and Medicare benefits.”

Differences in life expectancy between the rich and the poor can mean that more affluent Americans receive hundreds of thousands of dollars more in benefits that those who are less well off. In addition to the economic considerations, there is a psychological and perhaps even moral factor that comes into play when thinking about how long we might expect to live in relation to our financial status.

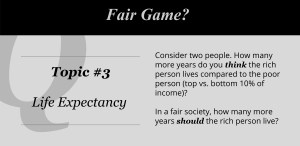

Topic 3 in Fair Game? asked users to think about exactly this question and to estimate how income is related to life expectancy and what that relationship should be in a fair world.

“It will surprise nobody to learn that life expectancy increases with income.”— Michael Specter, 4/16/16, The New Yorker

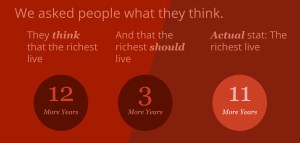

On the whole, our users estimated that the richest 10% of society would have a life expectancy 12 years longer than the poorest 10%. In reality, the difference is 11 years (12 additional years for men and 10.1 additional years for women).

How many more years of life do they think the wealthy should expect in a fair world? 3 more years (a 75% reduction from their estimate of what is true).

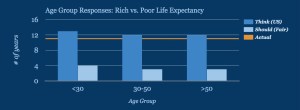

Estimates for the current difference in life expectancy were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair. Preferences for a fair difference were also similar. There may be hints of a difference between younger and older adults, with a possible explanation simply being ‘mortality salience’, or how much longer users themselves’ expect to live.

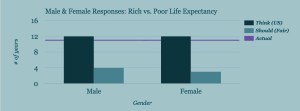

What about gender? Both males and females estimate 12 more years of life for the top 10%. But they differ slightly in what they think a fair amount of additional years would be — 4 vs. 3, respectively.

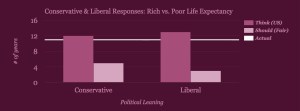

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal only differed by 1 year in terms of what they believed the life expectancy gain from wealth to be, and 2 years in what they thought it should be in a fair world. Conservatives estimate the gain to be 12 years, while liberals put it at 13 years. In terms of what they think would happen in a fair society, conservatives consider 5 years and liberals consider 3 years to be a fair number of years gained with wealth. Despite these small differences, the presumed improvement (from what is thought to what it should be) ends up being 7 years for conservatives vs. 10 years for liberals.

Together, the data reported here suggest that estimations of the present gap in life expectancy are fairly accurate. And that small differences in life expectancy (3-5 years) are considered fair (or perhaps tolerable) by most people. Has the wealth-based life expectancy gap always been this large? According to a Brookings report, it has actually grown from 4.5 years (for the cohort of seniors born in 1920) to 11 years (for the cohort born in 1940). It is likely that multiple factors, including differential access to quality medical care, and higher rates of smoking and obesity, contribute to the growth of this gap. On top of all of this, wealthier people typically retire later and can delay receiving social security payments, thereby increasing income inequality in the older population.

Unfortunately, public benefits that were originally intended to be progressive seem to be becoming (unintentionally) regressive over time. Perhaps there are some solutions that might help to keep more Americans living long, happy, and healthy lives?

What do you think? Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

The Meaning of Happiness Changes Over Your Lifetime

The following is a scientific and personal article written by CAH member Troy Campbell about happiness.

The following is a scientific and personal article written by CAH member Troy Campbell about happiness.

One lovely afternoon, I began chatting to my grandpa. I was completely unaware he was about to say something that would change my view of happiness forever.

In the middle of our conversation, I felt a lull so I pulled out the classic question. “If you could have dinner with one person, living or dead, who would it be?” I couldn’t wait to talk about my long list of dead presidents, dead Beatles, dead scientists, and a really cute living movie star. But I was also really eager to hear what he’d say.

Then he simply answered, “My wife.”

I immediately assured him it’s not necessary for him to answer like that. We all knew he loves his wife, whom he eats dinner with every night and was currently over in the other room playing cards.

He still insisted, “My wife. I’d have a nice dinner with my wife.”

“Alright,” I said, maybe a little too snappy, “Someone other than your wife.”

“Well okay, it would be my good friend and neighbor, Bill,” He replied.

The I became a little angry and pleaded, “Come on, you wouldn’t pick like John Lennon or Abraham Lincoln or FDR? He was alive when you were, right?”

“No. I’d pick Bill.”

I was just about to explain the point of the game again when it hit me. He already understood the game, and he was not trying to mess with me. What would make him most happy would be to have the same meal he has everyday, with the woman he’s been married to for 50 years.

Happiness to him was ordinary.

***

Over the past years, the interest in happiness has exploded. Everyone seems to want to be happy, read about how to be happy, or listen to Pharrells’ hit song, “Happy.” In response, researchers and gurus have been trying to feed everyone’s interest in happiness by pumping out new studies and New York Times bestsellers.

However, there’s been one factor that’s been missing in all this happiness discussion and in retrospect, it seems ridiculously obvious. That factor is age. As the story of my grandfather vividly displays, at different ages, we are interested in very different kinds of happiness.

Two young psychologists have recently stepped onto the scene and started to explain how happiness varies over the lifetime. Amit Bhattacharjee of Dartmouth University and Cassie Mogilner of the University of Pennsylvania find that the young find happiness and self-definition through extraordinary experiences, like meeting a celebrity. In contrast, older adults find happiness and self-definition through everyday experiences, like dinner with a best friend or wife.

To fully illustrate this concept, consider any family vacation. Think about how difficult it always is to make both the children and parents happy. This is because happiness means something different to younger and older members of the family.

The young crave the extraordinary. They long to bungee jump off a cliff, find a celebrity, and post a stylized Instagram photo that exaggerates the extraordinariness of the moment. Youth culture embraces the concept the of Yolo — “You Only Live Once” — which is just a modern (and arguably more annoying) way to say “carpe diem,” which is just a Latin way to say “seize the day.” Yolo is not something new; it’s just a rebranding of the youth mindset that’s always been around.

In contrast, older people tend to find happiness and define themselves in the ordinary experiences that comprise daily life. So, on vacation, parents often just want to spend time as a family. They want to have a nice family dinner and play card games.

What’s important about Bhattacharjee and Mogilner’s happiness hypothesis is that it is a psychological hypothesis rather than a cultural hypothesis. The scientists argue that with fewer days left in their lives, people start to focus on daily experiences and close-knit friendships. And that’s exactly what the researchers find through a controlled experiment. When they took 20-somethings and made them feel as if their brains would stop optimally functioning at age 40 (as opposed to age 80), the 20-somethings felt like they had less time left and were more interested in everyday happiness activities. They end up acting more like older people.

It’s worth noting that these findings greatly contrast the “Bucket List” hypothesis, the idea that as people feel their days are running out, they are motivated to do the extraordinary. For instance, in the film The Bucket List, two aging men strive to have the most extraordinary experiences possible. Though these cases do exist in society, they may be the exception. In general the rule is that as people feel like they are aging, they turn away from the extraordinary and, like my grandfather, focus on the everyday.

***

So if happiness is as important a goal in life as American culture makes it seem, we need to understand how age affects it. Only then can we know how to better treat our families, communities, and citizens of all ages. Only then will we all be happy, even if happy will mean different things to different people at different stages of their lives.

Burns and Happiness

The realization of how relative happiness is became very apparent to me some years ago when I was in the burn department.

One day a new patient came to the burn department — Miri, a teenage girl. Miri was 17 and her boyfriend just informed her that he was leaving her for someone else. As passionate as only teenagers can be, she went to the bathroom, slashed her wrists and poured bleach on them. As luck had it, when she was brought into the emergency room, Dr. Batya Yafe was there, an amazing woman and specialist in both plastic surgery and microsurgery who was able to reconstruct Miri’s blood vessels and take care of the damaged skin on her wrists.

A few weeks later Miri was a functional teenager again, but with second degree burns on her wrists. Relative to the rest of us, this was a relatively minor injury, but I am sure it was still very painful. The first few weeks were a serious adjustment for her – switching from being an active teenager in love to a patient in the burn department surrounded by these awful smells and many people in tremendous agony is not easy for anyone and particularly not for an idealistic teenager. The amazing thing was to see her a few weeks later and in the months to follow when she would come back to visit us. She seemed like a new and altogether person. She was happy, energetic, and with an appetite for life.

The scars that Miri carried on her wrists must have made her feel immensely different in the world outside the burn department, a constant reminder of her time spent in the burn department and the events that brought her there. I also suspect that these scars acted as a permanent reminder of what could have been, and her relative fortune in life. Was her newfound happiness related to the negative experience in the burn department? I imagine that Miri’s injury and her weeks in the burn department adjusted her perspective on life. Both the struggle she had with her burns, and the comparison to the other people in the burn department must have dwarfed her perceptions of her romantic trouble in comparison.

The burns on her wrists really helped Miri, and more generally I think that injuries that “work best” in giving people a new perspective on life are those that continuously act as a reminder of their relative happiness — even once the initial injury is over. Miri’s wrists, or losing a leg, for example, are promising on these grounds because the loss can act as a permanent reminder. And so are deep burns (the superficial ones are not as good because they can disappear with time). Lets be clear — I am not advocating burning people who are not very happy with their lives and letting them struggle with the pain and agony of burns, the slow recovery, and the comparison to other less fortunate individuals — but I do think that ironically such negative experiences can actually improve the outlook people have on life and their motivation for living.

So, as we plan for 2011 maybe we can find ways to be happy without any serious injuries.

Happy new year

Dan

Adaptation to new new circumstances? — happiness

An interesting story about research on well-being and our understanding of it was published today in the NYT. The issue is whether people get used to new life circumstances and, as a consequence, their long-term happiness (well-being) is not affected. Basically, a large body of research on well-being suggests that people in general become used to new circumstances to an extent that is beyond their, and others’, initial estimates (Diener and Diener 1996; Diener and Suh 1997; Gilbert et al. 1998; Kahneman 1999; Schkade and Kahneman 1998). For example, it has even been suggested that people who sustain a substantial injury are not much worse off than people who have not (Brickman, Coates, and Janoff-Bulman 1978). The story in the NYT describes some new research that questions these findings.

Here are some personal reflections on this topic:

(more…)

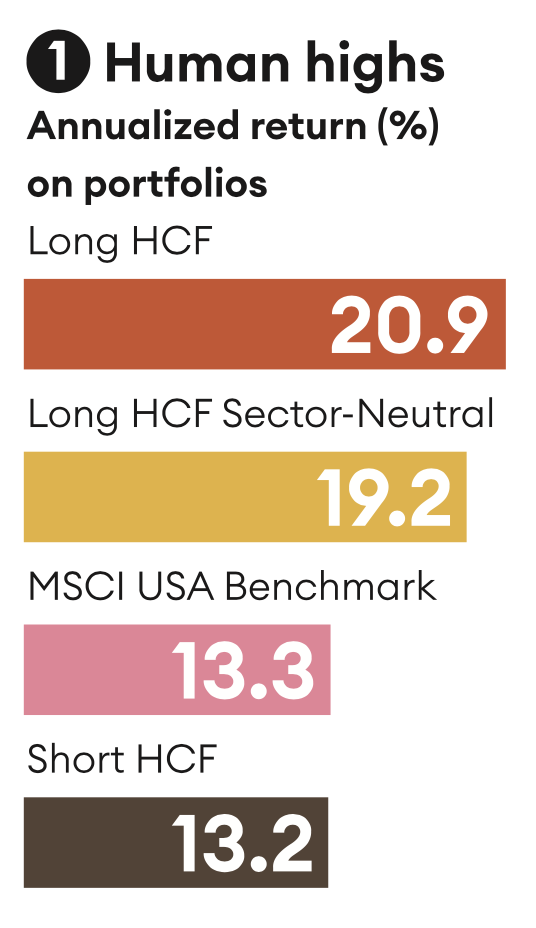

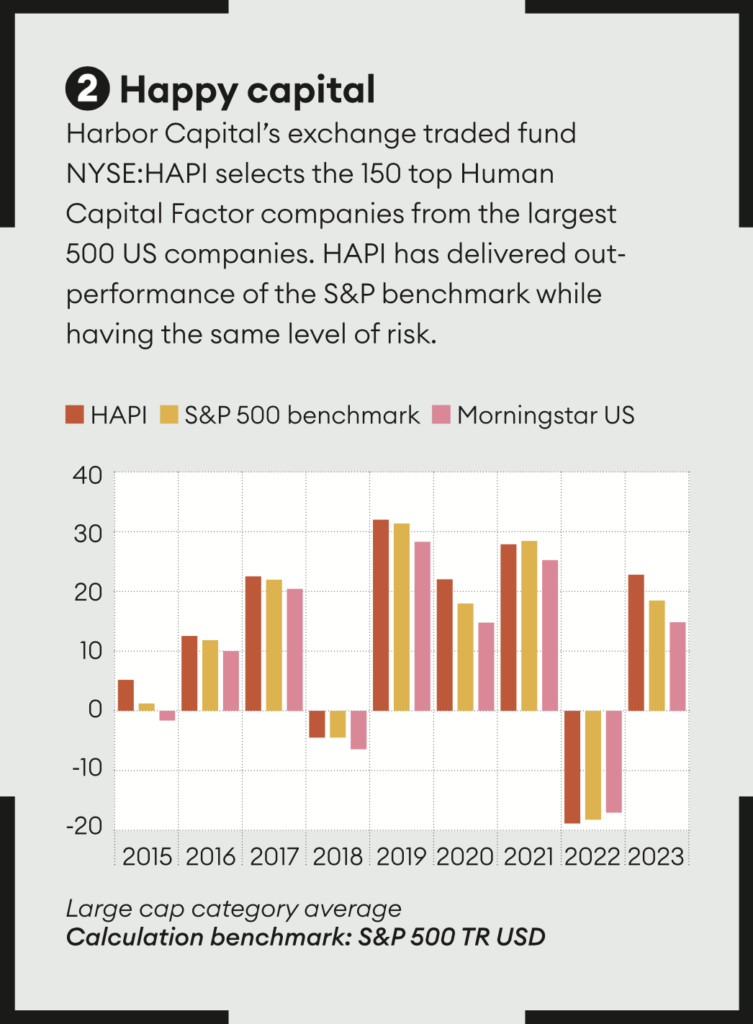

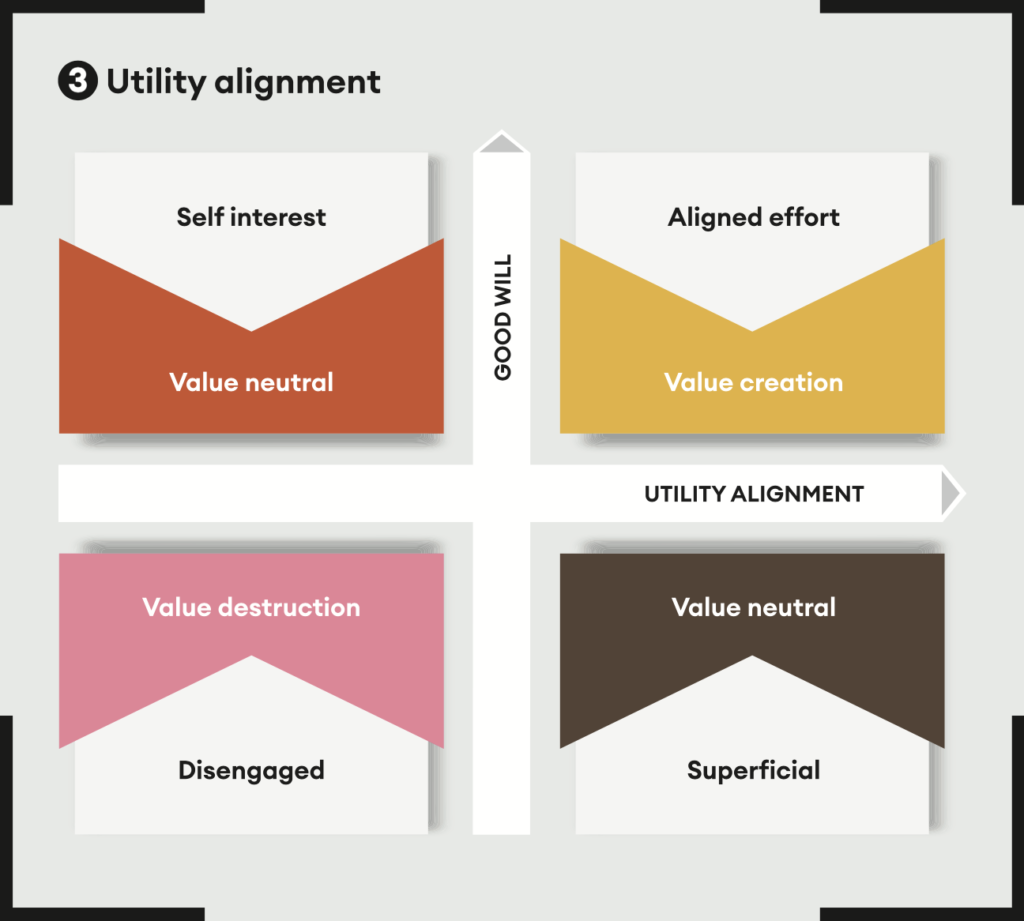

The human catalyst

A strong Human Capital Factor ignites growth.

“I only want to invest in fundamentals.” Such is a common statement from financiers. Yet these self-proclaimed ‘fundamental investors’ are people who regularly ignore a key aspect of a successful business.

Originally posted on December 1st 2023 here https://dialoguereview.com/the-human-catalyst/

Greater Goods

Episode description:

Do most of us, no matter our circumstances, generally land at about an 8 (out of 10) on the proverbial happiness scale? Does the human tendency to ruminate and reflect lead us toward or away from that happiness? What sort of person should we aim to be, particularly if something overwhelming and life-changing is going to happen?

In this final, retrospective episode of “The Upside of Down,” Dan and fellow social psychologist Paul Bloom examine the critical features that lead some people to give up when faced with extreme challenges, and others to persist. They also discuss why Dan chose to take on this project altogether, and how it could be an essential step toward deeply understanding the mechanisms of resilience.

Guest: Paul Bloom

Professor Emeritus of psychology and cognitive science at Yale University and Professor of Psychology at the University of Toronto

Ask Ariely: On Pleasing Presents and Sympathizing Sibling

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My aunt gave me some money for my birthday. Since she wasn’t sure about my likes and dislikes, she said to spend it on something that would make me happy. Do you have any advice on how to choose?

—Katy

While I’m sure there are many items that would make you happy, spending the money on someone else could make you even happier. In an experiment, researchers gave participants either $5 or $20. They then randomly asked the participants to go about their day and spend that money either on themselves or on someone else. Later, the researchers asked them about their happiness. Those who had spent the money on someone else, regardless of the amount, reported feeling happier throughout the day.

But what to buy these other people in order to get both the glow from gift-giving and something that they will like? A different set of researchers asked people to name the last gift that they had received and say how happy they were with it.

Though gift recipients were happy with items that they had wanted, on average they were even happier with unexpected and surprising gifts. These made them appreciate the thought from the sender and got them to experience something new. Hopefully your aunt will also appreciate how you choose to spend her gift money.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My sister is one of my closest friends, and she’s usually one of the first people I call when I need solid advice or someone to talk to. Our lives, however, are pretty different, and they are starting to differ more. Sometimes I hesitate to open up and ask for her advice because I’m not sure she can relate to what I’m going through. What should I do? Should I look for someone else to get feedback and advice from?

—Ingrid

It’s reasonable to think that it is best for someone to have “been there” in order to understand you and give you good advice. Indeed, a recent survey found that people predicted that a shared experience would lead to greater insights. But is that true?

In one experiment, participants listened to a short video describing a negative emotional experience. They were asked to analyze how the storyteller was feeling about the experience and also indicate if they had a similar story from their own past. The results showed that listeners who had a negative experience in common with a storyteller were much less accurate at describing how the storyteller felt.

It may be that people were more likely to focus on their own similar experience if they had one, which shifted their focus away from how the storyteller was feeling. These results suggest that even though someone has “been there,” they might not understand how you’re feeling in the moment you most need support.

So while your sister might not be going through the same things as you, that doesn’t mean she can’t empathize. In fact, her distance from your exact situation—but closeness with you—might give her a perspective nobody else can offer. Stick with your sister.

Ask Ariely: On Keepsake Conundrums and Proxy Practicality

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m planning a family reunion where relatives will be asked to bring photos and keepsakes. One side of the family, however, hasn’t been able to hold on to many physical memories, and I’m concerned that the lack of memorabilia will bring down the mood of the event. What’s the best way to handle this situation?

—Selena

Memories make us happier than we expect, even sad or seemingly mundane memories—and even memories that aren’t our own.

One study asked college students to write their favorite college memories on notecards. A month later the students read either their own memories or those of another student. Both groups reported boosts in happiness after writing and reading memories, even when the memories were about things that could be considered sad. The study was replicated in nursing homes in New Jersey: The residents who read memories, even ones that weren’t their own, reported feeling less lonely, more connected and happier.

These findings suggest that everyone at the reunion will be better off after looking at photos and scrapbooks. The reunion is also a great opportunity for family members to write down memories and stories that aren’t otherwise recorded, which could be a good start for enjoying memories at the next reunion.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently divorced after many years of marriage. Splitting our assets and accounts was a long and difficult process. Now I’ve discovered that my advance medical directive still has my ex-wife listed as my healthcare proxy. Should the situation arise, she can decide whether to keep me alive or disconnect me from life support. Should I find somebody else to take over this role or wait a bit, so as not to ruffle already hurt feelings or cause further practical headaches? What if I die in the meantime?

—Alec

You should certainly keep your ex-wife as your healthcare proxy, and not simply out of convenience or a desire to avoid giving offense.

As the doctor and medical writer Jerome Groopman has observed in one of his New Yorker Columns “Sometimes, however, a doctor’s impulse to protect a patient he likes or admires can adversely affect his judgment.” Dr Groopman then continues to describe one of his own cases: “I was furious with myself. Because I liked Brad, I hadn’t wanted to add to his discomfort and had cut the examination short. Perhaps I hoped unconsciously that the cause of his fever was trivial and that I would not find evidence of an infection on his body. This tendency to make decisions based on what we wish were true is what Croskerry calls an “affective error.” In medicine, this type of error can have potentially fatal consequences.”

My interpretation of Groopman’s observation is that it is often better for doctors not to have special feelings for their patients. Why? Because as lots of research has shown that it is difficult to be objective in making decisions for people we are attached to. We make more judicious decisions regarding people we care about less.

In your case, your ex-wife doesn’t care much about you these days. And because of that, should you sustain a serious injury or illness, the odds are in your favor that she will make more rational decisions on your behalf than she would have done during the days when she loved you deeply. Even if you do end up getting remarried, keep her as your healthcare proxy. There is no substitute for the rational coldness that comes from having your ex-wife make decisions for you.

This being said, don’t tempt her too much: Make sure she is not one of the beneficiaries of your will or life insurance.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like