Wait For Another Cookie?

The scientific community is increasingly coming to realize how central self-control is to many important life outcomes. We have always known about the impact of socioeconomic status and IQ, but these are factors that are highly resistant to interventions. In contrast, self-control may be something that we can tap into to make sweeping improvements life outcomes.

If you think about the environment we live in, you will notice how it is essentially designed to challenge every grain of our self-control. Businesses have the means and motivation to get us to do things NOW, not later. Krispy Kreme wants us to buy a dozen doughnuts while they are hot; Best Buy wants us to buy a television before we leave the store today; even our physicians want us to hurry up and schedule our annual checkup.

There is not much place for waiting in today’s marketplace. In fact you can think about the whole capitalist system as being designed to get us to take actions and spend money now – and those businesses that are more successful in that do better and prosper (at least in the short term). And this of course continuously tests our ability to resist temptation and for self-control.

It is in this very environment that it’s particularly important to understand what’s going on behind the mysterious force of self-control.

Several decades ago, Walter Mischel* started investigating the determinants of delayed gratification in children. He found that the degree of self-control independently exerted by preschoolers who were tempted with small rewards (but told they could receive larger rewards if they resisted) is predictive of grades and social competence in adolescence.

A recent study by colleagues of mine at Duke** demonstrates very convincingly the role that self control plays not only in better cognitive and social outcomes in adolescence, but also in many other factors and into adulthood. In this study, the researchers followed 1,000 children for 30 years, examining the effect of early self-control on health, wealth and public safety. Controlling for socioeconomic status and IQ, they show that individuals with lower self-control experienced negative outcomes in all three areas, with greater rates of health issues like sexually transmitted infections, substance dependence, financial problems including poor credit and lack of savings, single-parent child-rearing, and even crime. These results show that self-control can have a deep influence on a wide range of activities. And there is some good news: if we can find a way to improve self-control, maybe we could do better.

Where does self–control come from?

So when we consider these individual differences in the ability to exert self-control, the real question is where they originate – are they differences in pure, unadulterated ability (i.e., one is simply born with greater self-control) or are these differences a result of sophistication (a greater ability to learn and create strategies that help overcome temptation)?

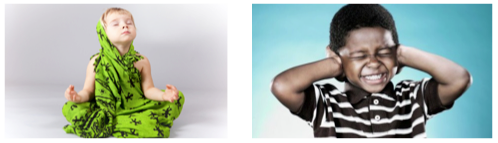

In other words, are the kids who are better at self control able to control, and actively reduce, how tempted they are by the immediate rewards in their environment (see picture on left), or are they just better at coming up with ways to distract themselves and this way avoid acting on their temptation (see picture on right)?

It may very well be the latter. A hint is found in the videos of the children who participated in Mischel’s experiments. It’s clear that all of the children had a difficult time resisting one immediate marshmallow to get more later. However, we also see that the children most successful at delaying rewards spontaneously created strategies to help them resist temptations. Some children sat on their hands, physically restraining themselves, while others tried to redirect their attention by singing, talking or looking away. Moreover, Mischel found that all children were better at delaying rewards when distracting thoughts were suggested to them. Here is a modern recreation of the original Mischel experiment:

A helpful metaphor is the tale of Ulysses and the sirens. Ulysses knew that the sirens’ enchanting song could lead him to follow them, but he didn’t want to do that. At the same time he also did not want to deprive himself from hearing their song – so he asked his sailors to tie him to the mast and fill their ears with wax to block out the sound – and so he could hear the song of the sirens but resist their lure. Was Ulysses able to resist temptation (the first path)? No, but he was able to come up with a very useful strategy that prevented him from acting on his impulses (the second path). Now, Ulysses solution was particularly clever because he got to hear the song of the sirens but he was unable to act on it. The kids in Mischel’s experiments did not need this extra complexity, and their strategies were mostly directed at distracting themselves (more like the sailors who put wax in their ears).

It seems that Ulysses and kids ability to exert self-control is less connected to a natural ability to be more zen-like in the face of temptations, and more linked to the ability to reconfigure our environment (tying ourselves to the mast) and modulate the intensity by which it tempts us (filling our ears with wax).

If this is indeed the case, this is good news because it is probably much easier to teach people tricks to deal with self-control issues than to train them with a zen-like ability to avoid experiencing temptation when it is very close to our faces.

*********************************************************

* Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez MI (1989) Delay of gratification in children. Science. 244:933-938.

** Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Houts R, Poulton R, Roberts B, Ross S, Sears MR, Thomson WM & Caspi A (2011) A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth and public safety. PNAS. 108:2693-2698.

Squash and Our Intuitive Strategic Thinking

As you may or may not know, I am a fairly avid squash player (not so good but I love the game). One of my favorite aspects of squash, aside from being a great source of exercise, is the strategic thinking required.

The other day while playing, I had a slight itch to change strategies. It wasn’t a conscious, logical process, and it was more like a kind of the desire to itch or pick a scab. Like picking a scab, my better judgment told me that making this switch would be a bad idea, but the urge was too great, and I switched my playing style. And it worked!

After the game I wondered, where does this itch come from? Is it part of our creative instinct for exploring and trying out new strategies? Do we have a desire to try new things?

When Firefighters Don’t Fight

Recently, a flaming trashcan ignited a house in Tennessee. Local authorities were notified and a crew of firefighters rushed to the scene to put out the fire just in time.

Wait a minute. That’s not at all what happened. In Obion County, firefighters are not on-call to the community at large. Instead, the right to a fireman is only guaranteed to those who pay an annual $75 fire protection fee before their property lights up. When this house (belonging to homeowners who had not paid the fee) caught fire, firefighters refused to come to the rescue. They ignored the family’s begging, only arriving at the scene when the fire jumped to a neighbor’s house (who had, in fact, paid for protection). Still, not a drop of water was wasted on the first house. Firefighters merely stood and watched as the house dissolved into ash.

This problem is related to the question of bailing out people with bad mortgages. Should we help those who took o mortgages that they could not afford? Would it encourage them in the future to keep on being reckless?

Or we can ask a more general question — should we actually let people decide whether they’d like to pay the advance protection fee, or is there something ultimately flawed about letting people decide for themselves? Very few of us think that we will be the ones in need of fire protection, and because we don’t foresee the consequences of not paying, we might not be sufficiently prepared for a potential disaster. And maybe we shouldn’t have to make that difficult decision ourselves.

Back to School #2

The Magic of Procrastination

Oscar Wilde once said, “I never put off till tomorrow what I can do the day after.” As a university professor, I constantly see Wilde’s words put into action. Each fall students arrive to the first day of class determined to meet deadlines and stay on top of their assignments. And each fall the human weakness to procrastinate gets the best of them. After a few years of witnessing this behavior, my colleague Klaus Wertenbroch and I worked up a few studies hoping to get to the root of this problem. Our guinea pigs were the delightful students in my class on consumer behavior.

As they settled into their chairs that first morning, I explained to them that they would have to submit three main papers over the 12-week semester and that these three papers would constitute a large part of their final grade. “And what are the deadlines?” asked one student. I smiled. “The deadlines are entirely up to you and you can hand in the papers any time before the end of the semester,” I replied. “But, by the end of this week, you must commit to a deadline for each paper. Once you set your deadlines, they can’t be changed. Late papers,” I added, “would be penalized at the rate of one percent off the grade for each day late.”

“But Professor Ariely,” asked another student, “given these instructions wouldn’t it make sense for us to select the last date possible?” “That’s an option,” I replied. “If you find that it makes sense, by all means do it.”

Now a perfectly rational student would set all the deadlines for the last day of class—after all, they could submit papers early, so why take a chance and select an earlier deadline than absolutely necessary? From this perspective, delaying the deadlines to the last day of he semester was clearly the best decision. But what if the students succumbed to temptation and procrastination? What if they knew that they are likely to fail? If the students were not rational and knew it, then they might set early deadlines and by doing so force themselves to start working on the projects earlier in the semester.

You would most likely predict that the students would succumb to procrastination (not a big surprise there)—but would they understand their own limitations and would they commit to earlier deadlines just to overcome their procrastination?

Interestingly, we found that the majority of students committed to earlier deadlines, and that this ability to commit resulted in higher grades. More generally, it seems that simply offering students a tool by which they could pre-commit publically to deadlines can help them achieve their goals.

How does this finding apply to non-students? When resolving to reach a goal—whether it is tackling a big project at work or saving for a vacation, it might help to first commit to a hard and clear deadline, and then inform our colleagues, friends, or spouse about it with the hope that this clear and public commitment will help keep us on track and ultimately fulfill our resolutions.

Back to School #1

The dark side of “Productivity Enhancing Tools”

Email, Facebook, and Twitter have greatly enhanced the ways we communicate. These handy modes of communication allow us to stay in touch with people all over the world without the restrictions of snail mail (too slow) or the telephone (is it too late/early to call?). As great as these communication tools are, they can also be major time-sinks. And even those of us who recognize their inefficiencies still fall into their trap. Why is this?

I think it has something to do with what the behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner called “schedules of reinforcement.” Skinner used this phrase to describe the relationship between actions (in his case, a hungry rat pressing a lever in a so-called Skinner box) and their associated rewards (pellets of food). In particular, Skinner distinguished between fixed-ratio schedules of reinforcement and variable-ratio schedules of reinforcement. Under a fixed schedule, a rat received a reward of food after it pressed the lever a fixed number of times—say 100 times. Under the variable schedule, the rat earned the food pellet after it pressed the lever a random number of times. Sometimes it would receive the food after pressing 10 times, and sometimes after pressing 200 times.

Thus, under the variable schedule of reinforcement, the arrival of the reward is unpredictable. On the face of it, one might expect that the fixed schedules of reinforcement would be more motivating and rewarding because the rat can learn to predict the outcome of his work. Instead, Skinner found that the variable schedules were actually more motivating. The most telling result was that when the rewards ceased, the rats that were under the fixed schedules stopped working almost immediately, but those under the variable schedules kept working for a very long time.

So, what do food pellets have to do with e-mail? If you think about it, e-mail is very much like trying to get the pellet rewards. Most of it is junk and the equivalent to pulling the lever and getting nothing in return, but every so often we receive a message that we really want. Maybe it contains good news about a job, a bit of gossip, a note from someone we haven’t heard from in a long time, or some important piece of information. We are so happy to receive the unexpected e-mail (pellet) that we become addicted to checking, hoping for more such surprises. We just keep pressing that lever, over and over again, until we get our reward.

This explanation gives me a better understanding of my own e-mail addiction, and more important, it might suggest a few means of escape from this Skinner box and its variable schedule of reinforcement. One helpful approach I’ve discovered is to turn off the automatic e-mail-checking feature. This action doesn’t eliminate my checking email too often, but it reduces the frequency with which my computer notifies me that I have new e-mail waiting (some of it, I would think to myself, must be interesting, urgent, or relevant). Another way I am trying to wean myself from continuously checking email (a tendency that only got worse for me when I got an iPhone), is by only checking email during specific blocks of time. If we understand the hold that a random schedule of reinforcement has on our email behavior, maybe, just maybe we can outsmart our own nature.

Even Skinner had a trick to counterbalance daily distractions: As soon as he arrived at his office, he would write 800 words on whatever research project he happened to be working on—and he did this before doing anything else. Granted, 800 words is not a lot in the scheme of things but if you think about writing 800 words each day you would realize how this small output can add up over time. I am also quite certain that if Skinner had email he would similarly not have checked it before putting in a few hours of productive work. Now if we could only learn something from one of the world’s experts on learning….

Procrastination and self control

Shaving, Squash, and my birthday

The Internet and Self-Control: An App To the Rescue

I have “a friend” who will head over to a coffee shop to get work done. Not because she’s unable to work at her desk or because she needs the presence of other people, but rather because it lets her get away from the Internet and all its distractions.

True, she could easily stay put by just keeping her browser closed. But that requires self-control, and as we all know, keeping ourselves in check is easier said than done. Whatever the resolution (start dieting, start saving, stop procrastinating, etc.) we routinely stick to it for a bit and then cave. We make the resolution in one state of mind – a cool, rational state – and then break it when temptation strikes.

That’s the reason for my friend’s coffeeshop strategy: precommitments allow us to commit upfront to our preferred course of action. In her cool, rational state, my friend can decide not to surf the web and make a point to leave the wireless behind; later, when temptation strikes, she’ll be out of luck. Access denied.

On the whole, I like my friend’s strategy. But there’s a potential problem: what if she needs the Internet to do her work? What then?

Not to worry – there’s an app to the rescue: SelfControl, a free Mac-only software program that blocks access to incoming/outgoing mail servers and websites and was thought up by artist Steve Lambert. (As the son of an ex-monk and an ex-nun, he’s well-versed in self-control.) The app only takes seconds to install and comes with all the flexibility that my friend’s coffeeshop strategy lacks.

Instead of taking leave of the Internet all-together, you can pick and choose what you can and can’t access, and for how long. If Facebook is your particular time-suck, then add its URL to SelfControl’s blacklist and the program will block Facebook and nothing else. If Twitter is another danger zone, then by all means, throw its URL into the mix. Next, figure out how long you want to block them for – anywhere from one minute to twelve hours – and move the slider accordingly. Then press start and you’re good to go.

But here’s the key part: once you click start, there’s no going back. (No wonder the app has a skull and crossbones symbol as its icon.) Switching browsers won’t help you, and neither will restarting your computer or even deleting the app. You won’t get those websites back until the timer runs out. As such, it’s as effective of a precommitment as seeking out a wireless-free zone.

Though temptation routinely deflects us from our long-term goals, our struggle with self-control isn’t a lost cause. Once we realize and admit our weakness, we can do something about it by taking on clever precommitments that save us from ourselves. In an ideal world we wouldn’t need the SelfControl app, but in this world it sure is useful.

Irrationally Yours,

Dan

P.S. For more on precommitments, check out this post on self-control and sex.

Sex, Shaving, and Bad Underwear

Sex, Shaving, and Bad Underwear

Or how to trick yourself into exerting self-control

Recently, I gave a lecture on the problem of self-control. You know the one: At time X you decide that you’re done acting a certain way (No more smoking! No more spending! No more unprotected sex!), but then when temptation strikes, you go back on your word.

As I mention in Predictably Irrational, this predicament has to do with our inherent Jekyll-Hyde nature: We just aren’t the same person all the time. In our cold, dispassionate state, we stick to our long-term goals (I will lose ten pounds); but when we become emotionally aroused, our short-term wants take the helm (Oh but I am hungry, so I’ll have that slice of cake). And what’s worse, we consistently fail to realize just how differently we’ll act and feel once aroused.

Fortunately, there’s a way around the problem: pre-commitments, or the preemptive actions we can take to keep ourselves in check. Worried you’ll spend too much money at the bar? No problem, bring just the cash you’re willing to part with. Afraid you’ll skip out on your next gym visit? All right, then make plans to meet a friend there. And so on. Pre-commitments can take many a form, and some get pretty creative.

For example, I surveyed my audience at the lecture hall for their pro-self-control tactics, and I received two noble suggestions. One woman reported that when she goes out on a date with someone she shouldn’t bed, she makes a point to wear her granniest pair of granny underwear. Similarly, another woman said that when faced with that kind of date, she just doesn’t shave.

Both are great ideas, I think, and are likely to work — well they’re certainly better than only relying on the strength of your self-control — but there is a risk. Let’s say the woman with the ugly underwear finds herself uncontrollably attracted to her date and decides that, you know what, ugly underwear be damned, there will be sex tonight! Chances are she will wake up in the morning wishing she had worn her silk lingerie after all.

Irrationally yours

Dan

p.s if you have any personal self control stories that you are willing to share — please send them my way

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like