In compliance with a federal integrity agreement, pharmaceutical giant Pfizer released details of its financial involvement with the medical community.

According to the New York Times, the drug maker disclosed that it paid $20 million in consulting and speaking fees to 4,500 doctors in the second half of 2009. The company also shelled out $15.3 million to U.S. academic medical centers for their clinical trials.

A few other drug makers have disclosed their payments to physicians in the past, but this is the first time a company has disclosed its payments for clinical trials. As such, some may see this as a good deed on Pfizer’s part, a noble step towards eliminating or reducing some of the conflicts of interest in medicine.

Only, disclosure doesn’t seem to help. Several studies have shown that when professionals disclose their conflicts of interest, this only makes the problem worse. This is because two things happen after disclosure: first, those hearing the disclosure don’t entirely know what to make of it — we’re not good at weighing the various factors that influence complex situations — and second, the discloser feels morally liberated and free to act even more in his self-interest.

So, in this case the people who run Pfizer will likely feel even more entitled to disregard the public good, and the public, in turn, will not know what to make of the numbers it released. After all, what do you make of the numbers? It’s hard to figure out from a statement of disclosure just how much influence the conflict of interest had on the discloser, and to what degree we should be wary of them as a result.

The real issue here is that people don’t understand how profound the problem of conflicts of interest really is, and how easy it is to buy people. Doctors on Pfizer’s payroll may think they’re not being influenced by the drug maker — “I can still be objective!” they’ll say — but in reality, it’s very hard for us not to be swayed by money. Even minor amounts of it. Or gifts. Studies have found that doctors who receive free lunches or samples from pharmaceutical reps end up prescribing more of the company’s drugs afterwards.

It’s just a fact of human life: we are compelled to reciprocate favors, and an ingrained inability to disregard what’s in our financial interest. As author Upton Sinclair said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

In recent years there seems to have been a surge in academic dishonesty in high schools. No doubt this can be explained in part by 1) increased vigilance and reporting, 2) greater pressure on students to succeed, and 3) the communicable nature of dishonest behavior (when people see others do something, whether it’s enhancement of a resume or parking illegally, they’re more likely to do the same). But, I also think that a fourth, and significant, cause in this worrisome trend has to do with the way we measure and reward teachers.

To think about the effects of these measurements, let’s first think about corporate America, where measurement of performance has a much longer history. Recently I met with one of the CEOs I most respect, and he told me a story about when he himself mismanaged the incentives for his employees, by over-measurement. A few years earlier he had tried to create a specific performance evaluation matrix for each of his top employees, and he asked them to focus on optimizing that particular measure; for some it was selection of algorithms, for others it was return on investment for advertising, and so on. He also changed their compensation structure so that 10 percent of their bonus depended on their performance relative to that measure.

What he quickly found was that his top employees did not focus 10 percent of their time and efforts on maximizing that measure, they gave almost all of their attention to it. This was not such good news, because they began to do anything that would improve their performance on that measure even by a tiny bit—even if they caused problems with other employees’ work in the process. Ultimately they were consumed with maximizing what they knew they would be measured on, regardless of the fact that this was only part of their overall responsibility. This kind of behavior falls in line with the phrase “you are what you measure,” which is the idea that once we measure something, we make it salient and motivational. In these situations people start over-focusing on the measurable thing and neglect other aspects of their job or life.

So how does this story of mis-measurements in corporate America relate to teaching? I suspect that any teachers reading this see the parallels. The mission of teaching, and its evaluation, is incredibly intricate and complex. In addition to being able to read, write, and do some math and science, we want students to be knowledgeable, broad-minded, creative, lifelong learners, etc etc etc. On top of that, we can all readily agree that education is a long-term process that sometimes takes many years to come to fruition. With all of the complexity and difficulty of figuring out what makes good teaching, it is also incredibly difficult to accurately and comprehensively evaluate how well teachers are doing.

Now, imagine that in this very complex system we introduce a measurement of just one, relatively simple, criteria: the success of their students on standardized tests. And say, on top of that, we make this particular measurement the focal point of evaluation and compensation. Under such conditions we should expect teachers to over-emphasize the activity that is being measured and neglect other aspects of teaching, and we have evidence from the No Child Left Behind program that this has been the case. For example, we find that teachers teach to the test, which improves the results for that test but allows other areas of education and instruction (that is, those areas not represented on the tests) to fall by the wayside.

And how is this related to dishonesty in the school system? I don’t think that teachers are cheating this way (by themselves changing answers, or by allowing students to cheat) simply to increase their salaries. After all, if they were truly performing a cost-benefit analysis, they would probably choose another profession—one where the returns for cheating were much higher. But having this single measure for performance placed so saliently in front of them, and knowing it’s just as important for their school and their students as it is for their own reputation and career, most likely motivates some teachers to look the other way when they have a chance to artificially improve those numbers.

So what do we do? The notion that we take something as broad as education and reduce it to a simple measurement, and then base teacher pay primarily on it, has a lot of negative consequences. And, sadly, I suspect that fudging test scores is relatively minor compared with the damage that this emphasis on tests scores has had on the educational system as a whole.

Interestingly, the outrage over teachers cheating seems to be much greater than the outrage over the damage of mis-measurement in the educational system and over the No Child Left Behind Act more generally. So maybe there is some good news in all of this: Perhaps we now have a reason to rethink our reliance on these inaccurate and distracting measurements, and stop paying teachers for their students’ performance. Maybe it is time to think more carefully about how we want to educate in the first place, and stop worrying so much about tests.

(This post also appeared as part of a leadership roundtable on the right way to approach teacher incentives in the Washington Post. The Washington Post will post more opinions about this topic here. )

My 2-year cell phone contract was up last month, and even before the date when I could opt for an upgrade, I began to experience the pain of indecision: which was it going to be – a Samsung Galaxy S3 or an iPhone 5? I was one of the only Android (HTC Evo) users in our Center for Advanced Hindsight team, and swayed by the rest of the group’s dedication to Apple, I was looking forward to switching to the new iPhone as soon as my contract was up. But I was not going to be able to befriend the newest iOS 6-adorned Siri until the iPhone’s release in a couple of months. In today’s impatient tech age, that is an eternity. My longing for an Apple clashed with my itching desire to get a new phone.

My 2-year cell phone contract was up last month, and even before the date when I could opt for an upgrade, I began to experience the pain of indecision: which was it going to be – a Samsung Galaxy S3 or an iPhone 5? I was one of the only Android (HTC Evo) users in our Center for Advanced Hindsight team, and swayed by the rest of the group’s dedication to Apple, I was looking forward to switching to the new iPhone as soon as my contract was up. But I was not going to be able to befriend the newest iOS 6-adorned Siri until the iPhone’s release in a couple of months. In today’s impatient tech age, that is an eternity. My longing for an Apple clashed with my itching desire to get a new phone.

After watching a hopeless number of face-off videos, reading about the features and specs of Galaxy S3 compared with the endless mock ups of the rumored iPhone 5, and even throwing the question around at dinner parties, I decided to come to my senses, listen to what research has to say, and make an irrationally rational decision. Though surely evidence from decades of research is not limited to the following considerations, I picked a number of conceptual tools from decision-making research that could help shed light on this quandary of iPhone vs. Samsung:

- Now vs. Later: I should pit my short-term interest in having a new smartphone now against my long-term interest in having an iPhone later. Temporal discounting suggests that we have the tendency to want things now rather than later, and delaying gratification depends on whether we are convinced that what will happen in the future is going to be better than what we can have now. In other words: howmuch better is this nebulous iPhone of the future when I could have this immediately awesome Galaxy S3? Given that the specs of Galaxy S3 are available but those of the iPhone 5 are not, it might be smart to bet for what is certain. (Winner: Galaxy S3)

- Misremembering the past vs. mispredicting the future: I can go with the certain specs of Galaxy S3, or potentially recall my past experiences with iPhones and decide accordingly. Sadly we are bad at remembering past feelings; rather than correctly weighing the positives and negatives we remember the peak moments and selected experiences. Since I am unable to accurately recall my past emotional states, then maybe I can imagine how much pleasure each of these phones could bring me in the future? Unfortunately, we are also notoriously bad at predicting the duration and intensity of future feelings. (Winner: Galaxy S3)

- Want vs. need: Do I want a new phone? Yes. Do I really need a new phone? No, because my old one is still in good shape. With the irresistible discounts of signing up for a new 2-year plan, I am conditioned by the cell phone market to switch to a new phone as soon as possible. This conditioning moves me from casually wanting a new device to absolutely needing it to survive (!). I feel that the longer I wait, the more I am giving up on a perceived opportunity. (Winner: wait until my current phone gives up, and then get an iPhone 5).

- Decoy options iPhone 4s vs. HTC Evo: In my indecision, I can introduce a third option that is asymmetrically dominated either by Galaxy S3 or iPhone 5. If I consider iPhone 4S as a potential option, it would (hopefully) be dominated by iPhone 5 but could still be superior to the Galaxy S3 with the ease of its use, compactness and such. If I am leaning more towards the Android options, then I can consider staying with HTC Evo as a potential third choice, and given that Galaxy S3 surpasses my old Android in nearly every domain, I would lean towards upgrading to Samsung. (Winner: Depends on the decoy option)

- Reactance to unavailability: The brands also complicate the issue as they control supply and increase demand by playing with the availability of their products as well as the timing of their release. This can create several types of responses:

- Since iPhone 5 is currently unavailable, I experience a pressure to select iPhone 4S which is a similar alternative. If I perceive this as a limitation on my freedom to choose, I might react by selecting a dissimilar option. (Winner: Galaxy S3)

- The unavailability of iPhone 5 could also lead me to perceive it as more desirable. (Winner: iPhone 5)

- Or I can just despise what I can’t have. (Winner of the sour grapes story: Galaxy S3)

So, what should I do? Given the considerations above, there is still no clear winner for me. Yes, I have the plague of newism: I run after the genuine, exciting proposition of the emerging trends and products. Yes, I know there is something good now, but possibly something better around the corner.

At the end of the day, I will toss a coin: not because it will settle the question for me, but because in that brief moment when the coin is in the air, I will suddenly know which side I hope to see when it lands in my palm. And besides, whether I purchase my new phone from Apple or from Samsung, I will stick to my commitment, almost immediately forget about the forsaken option, and justify my choice infallibly in retrospect.

~Lalin Anik~

According to an article in SmartMoney, as many as 48% of U.S. dentists have seen their profits plummet thanks to the recession.

In and of itself, this isn’t a particularly remarkable statistic – after all, most of our wallets have taken a hit this past year – but what follows is an interesting discussion: how are dentists coping with this drop in income? Angie C. Marek reports a variety of tactics in her article (including lowered rates, freebies, eliminated IOUs, etc.), most of which benefit the patient – but they don’t all. Some dentists are softening the financial blow by upselling and overtreating patients.

One example came from a woman who, upon switching cities and dentists, was surprised to learn that her hitherto problem-free mouth was suddenly rife with problems: several cavities required coatings and two veneers needed replacement. Or so her dentist told her. However, this turned out to be just another case of overtreatment.

The problem here is conflicts of interests (COIs), which are instances when professionals are pulled in two directions, torn between personal gain and the good of the patient. And the sad news is that when faced with COIs dentists (or physicians) sometimes end up going the self-interested route, and this can have undesirable consequences for the patient.

Conflicts of interest are nothing new, they have been a problem for as long as there have been professions, and they are very pervasive. For instance, there’s the doctor who at accepts consulting fees from a drug company and studies their drug, the one who prescribes the treatment a drug rep pushed on him the week before over a free lunch, and even the doctor who urges a treatment on a patient in part so that he can use his costly new medical equipment.

This isn’t to say that these are dishonorable people who only see dollar signs and say to hell with the patient. Rather, COIs can deeply color the person’s perception, and thereby end up leading even the most upstanding citizens astray, and this happens often.

The long and short of it is, next time you are at the dentist’s office – think about your dentist’s conflicts of interests.

On the first day of one of my classes, I asked my undergraduate students whether they had enough self-control to avoid using their computers during class for non-class-related activities. They promised that if they used their laptops, it would only be for course-related activities like taking notes. However, as the semester drew on, I noticed more and more students checking Facebook, surfing the web, and emailing. And I noticed that as these behaviors increased, so did their cheating on weekly quizzes. In a class of 500 students, it was difficult to manage this deterioration. As my students’ attention and respect continued to degrade, I became increasingly frustrated.

Finally, we got to the point in the semester where we covered my research on dishonesty and cheating. After discussing the importance of ethical standards and honor code reminders, two of my students took it upon themselves to run something of an experiment on the rest of the students. They sent an email to everyone in the class from a fabricated (but conceivably real) classmate, and included a link to a website that was supposed to contain the answers to a past year’s final exam. Half the students received this email:

———- Forwarded message ———-

From: Richard Zhang <richardzhang44@gmail.com>

Subject: Ariely Final Exam Answers

To:

Hey guys,

Thought you might find this useful. See link below.

——————————————-From: Ira Onal<ira.onal@gmail.com>

To: Richard Zhang < >

Subject: Re:Hello!

Hey Richard,

Good to hear from you again. Yes, I was the TA for Ariely’s class. Here’s a link with the answers from the test when I was TA, and I don’t think he changes the questions/answers every semester. Hope this is helpful and let me know if you have any questions:

http://dl.dropbox.com/u/26171004/iraonal.html

Best of luck,

Ira

Ira T. Onal

Duke University Trinity School ’09

ira.onal@gmail.com | (410) 627-0299

Richard Zhang < > wrote:

> Hey Ira,

> I hope all is going well. I’m in Ariely’s class and saw your name on the syllabus – are you/were you the TA? I also heard there is an exam in the class, and was wondering if you had any guidance/tips for it. He just has a bunch of short quizzes this year, so should I use those to study from?

>Best,

Richard

–

Richard Zhang

Duke University ’12

(315) 477-1603

——————————————-

The other half got the same email but also included the following message:

~ ~ ~

P.S. I don’t know if this is cheating or not, but here’s a section of the University’s Honor Code that might be pertinent. Use your own judgment:

“Obtaining documents that grant an unfair advantage to an individual is not allowed.”

~ ~ ~

Using Google Analytics, the students tracked how many people from each group visited the website. The disparaging news is that without the honor code reminder, about 69% of the class accessed the website with the answers. However, when the message included the reminder about the honor code, 41% accessed the website. As it turns out, students who were reminded of the honor code were significantly less likely to cheat. Now, 41% is still a lot, but it is much less than 69%.

The presence of the honor code, as well as the ambiguity of the moral norm, may have had a role in the students’ behavior. When the question of morality becomes salient, students are forced to decide whether they consider their behavior to be cheating – and presumably most of them decided that it is.

Moreover, a qualitative look at the email responses from students (to the fictitious student who sent them the link to the test answers) showed that while those who did not see the code were generally thankful, those given the honor code were often upset and offended.

***

The issue of cheating arose again with the approach of finals. I received several emails from students who were concerned about their classmates cheating, so I decided to look into the situation with a post-exam survey. The day after the exam, I asked all the students to report (anonymously) their own cheating and the cheating they suspected of their peers.

The results showed that while the students estimated that ~30-45% of their peers had cheated on the final exam, very few of them admitted that they themselves had cheated. Now, you might be thinking that we should take these self-reports with a grain of salt – after all, even on an anonymous survey, students will most likely underreport their own cheating. But we can also look at the grades on the exam, and because less than 1% of students got a 90% or better (and the average got 70% correct), I am relatively confident that the students’ perception of cheating was much more exaggerated than the actual level (or they could just be very bad at cheating).

While it may seem like good news that fewer of their peers cheat than they suspect, in fact such an overestimation of the real amount of cheating can become an incredibly damaging social norm. The trouble with this kind of inflated perception is that when students think that all of their peers are cheating, they feel that it is socially acceptable to cheat and feel pressured to cheat in order to keep up. In fact, a few students have come to my office complaining that they were penalized because they decided not to cheat — and what was amazing to me was that in being honest, they truly felt that there was some injustice done to them.

The bottom line is that if people perceive that cheating is running rampant, what are the chances that next year’s students will adopt even more lenient moral standards and live up to the perception of cheating among their peers?

We once ran a study on cheating where we asked students to try to recall the Ten Commandments before an exam, and found that this moral reminder deterred them from cheating. Well, a professor at Middle Tennessee State University recently made practical use of the study – but in an extreme way.

Fed up with the low ethical standards among his MBA students, Professor Michael Tang passed out an honor pledge that not only listed the Ten Commandments, but also included a concluding flourish indicating that those who cheated would “be sorry for the rest of [their] life and go to Hell.” In response, several students called the department chair to complain and a good deal of controversy ensued.

But what the news coverage didn’t address (perhaps because no one at the school had) were the merits of this extreme pledge. Might this be an effective way of curbing dishonesty? I think yes, very much so. I also suspect that even those who don’t believe in God would take this pledge seriously.

Still, though I don’t doubt its effectiveness, the question remains whether we want to invoke such stringent punishments (stringent for those who believe, that is) on an MBA exam. Judging from the reactions in this case, I’m guessing that for most people, the answer is “no.” But it also makes me wonder about the people who didn’t want to sign this pledge….

After meeting her through a friend from graduate school, the editor of Harper’s Bazaar invited me to give a talk at the magazine headquarters. It was my first experience presenting at a fashion magazine and I suspect it may have been their first experience hosting an academic speaker. They were very gracious and interested (or at least they appeared to be), and they laughed where I hoped they would and asked thoughtful questions.

As a thank-you gift, they gave me a Prada overnight bag. Now, Apple products are the closest I have ever come to owning anything from a highly recognized brand, so acquiring this bit of couture was an interesting experience for me. As I made my way through JFK, I tried to decide whether I should hold the bag so that the triangular Prada logo was visible to other travelers or if I should keep it facing towards me. I quickly decided to keep the logo facing me, and began thinking about the role of brands in people’s lives.

We usually think of brands as signaling something to others. We drive Priuses to show that we are environmentally conscious or wear Nike to show that we’re athletic. In this case I didn’t want to send a signal to the world, but nevertheless I felt different, as if I were signaling something to myself—telling myself something about me and as a result of carrying the Prada bag.

Maybe this is the attraction of branded underwear. They are basically a private consumption experience, but my guess is that if I put on a pair of Ferrari underwear, even if nobody saw them, they would still make me feel differently somehow (Perhaps more masculine? Wealthier? Faster?).

The thing is, I realized I couldn’t just try to make myself feel better by imagining myself wearing Ferrari underwear. I would have to actually wear them in order to feel differently.

So brands communicate in two directions: they help us tell other people something about ourselves, but they also help us form ideas about who we are.

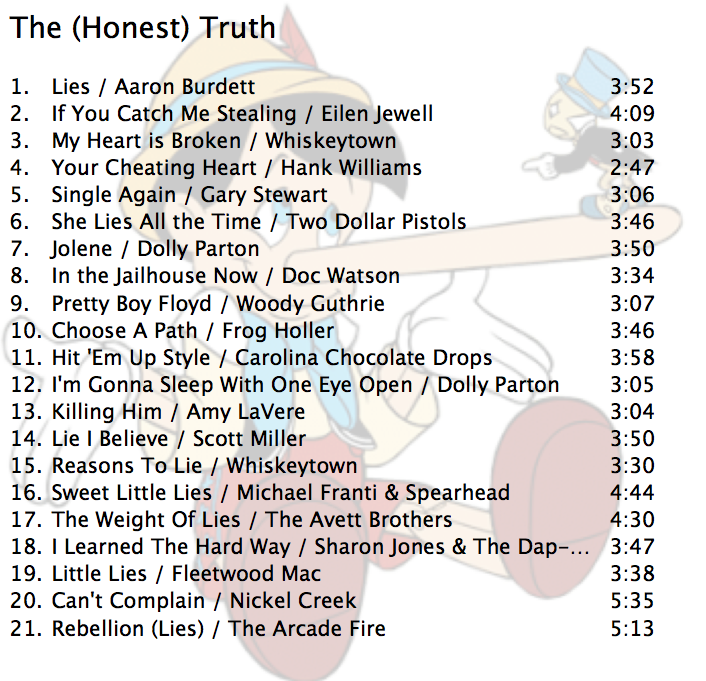

Tomorrow, Friday, at 7 PM I will talk about The Honest Truth at the Regulator bookstore in Durham NC.

This is the list of songs that they have created to play in the store for the day. I am just wondering if these songs will make the people in the store (employees and customers) more dishonest compared to a regular day…..

I am pleased to announce that I will be hosting a live book talk on Shindig (http://www.shindigevents.com/) , a new customized video chat space for live events. We will be connected globally via webcam online, and can interact and participate in a live talk about Honesty and Dishonesty. You can socialize with other participants, or watch and listen. The event will be on Monday July 2nd at 6pm EST.

Here’s how it works. About 15 minutes before it starts, go to this link and log in (http://www.shindig.com/event/dan-ariely). You should test your microphone and camera at this time. Then when the event starts we can get going. We will have an interactive talk about irrationality, honesty and dishonesty, followed by a question and answer session.

The only way to make this interesting and fun is to have people in attendance. So please invite as many of your friends as you like to join us! Spread the word on Facebook and Twitter to as many people as you can.

Honestly* yours

Dan Ariely

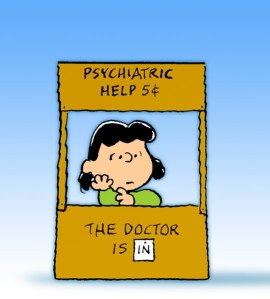

Starting next week, the doctor is in! I’m teaming up with The Wall Street Journal to offer answers to readers’ questions sent to IdeasMarket@wsj.com. Whether it’s about family matters, work conundrums, in-law issues, or where to take your next vacation, I’m happy to have the chance to let you sprawl out on my e-couch and provide some (hopefully useful) advice. And it won’t cost you a dime. Or a nickel.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like