How many of our emails should we know about the moment someone decides to email us?

205 billion. That’s the number of emails we sent and received in 2015, and that number is expected to grow to 246 billion by 2019.[1] What does this mean for most of us? A steady stream of new messages coming into our inboxes throughout the day. And for most of us, it seems to be a norm to keep our inboxes open throughout the work day. We focus on the tasks we have at hand, and each “ping” from our inbox draws our attention, even if briefly, before we return back to our work.

The problem here is the high cost of interruption. This cost includes three categories: 1) time cost 2) performance cost 3) stress/ emotional well-being.

Time Cost In terms of time cost, researches have shown that any switching between tasks results in a loss of time. In other words, “multi-tasking” is a misnomer – we aren’t actually doing two tasks at once. We are doing one task, switching to the other, and then switching to the original task. One study showed that after switching tasks, it took an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds for people to get back to their original task.[2]

Performance Cost It should be no surprise to us that distraction can cause reductions in cognitive performance. In psychological terms, “task-irrelevant thoughts,” that is – thoughts that are unrelated to the task at hand, have indeed been shown to have deleterious effects on performance.[3]

A recent study published in The Journal of Experimental Psychology illustrates how this plays out for cell phones in particular, focusing on the distraction that cell phone notifications can create. In this study, participants were tasked with completing a task involving seeing items and pressing a button every time the item was a digit from 1-9, unless it was the number 3. Some were interrupted with notifications and others were not. The study found that the notification groups were more likely to make errors than the no-interruption group.

Stress/Emotional Well-Being A third factor to consider with interruptions is the effect they have on people’s well being. Task switching is fatiguing for us; it depletes us. One study showed that interruptions resulted in higher feelings of stress, pressure and effort.[4]

At this point, it should be painfully clear to us that we need to be worried about the interruptions-economy. What value interruptions provide, under what conditions, and what are their costs? A little ping may seem innocuous, but there is cumulating evidence that the cost of an interruption is higher than we realize, and of course given the sheer number of interruptions, their combined effect can very quickly become substantial.

If email interruptions can have all these negative effects, what can we do to reduce them? The first thing we should question is this idea that all emails are created equal. Should each email be able to interrupt people? Is the email from someone’s boss as important as the weekly industry newsletter he’s signed up for? What if we designed a different system in which emails were not treated equally?

In a previous study, we looked at how many emails truly are worthy of interruption. We asked people to look at the last 40 emails they received and asked them how soon they really needed to have seen each email. Immediately? At some point today? At some point this week? At some point this month? No need to see it at all?

As it turns out, very few – only 12%! – of emails need to be seen within 5 minutes of being sent.

7% of emails need to be seen within 1 hour, 4% within 4 hours, 17% by the end of the day, 10% by the end of the week, 15% at some point, and a whopping 34% fell into the “no need to see it” category.

With that initial starting point – the idea that very few emails need to be seen right away – we set out to build a tool to allow people create rules for receiving emails. We used a very simple sorting technique: sorting emails based on the sender. In other words, depending on the sender, emails could be set to be received at different intervals. No complex AI or learning mechanisms.

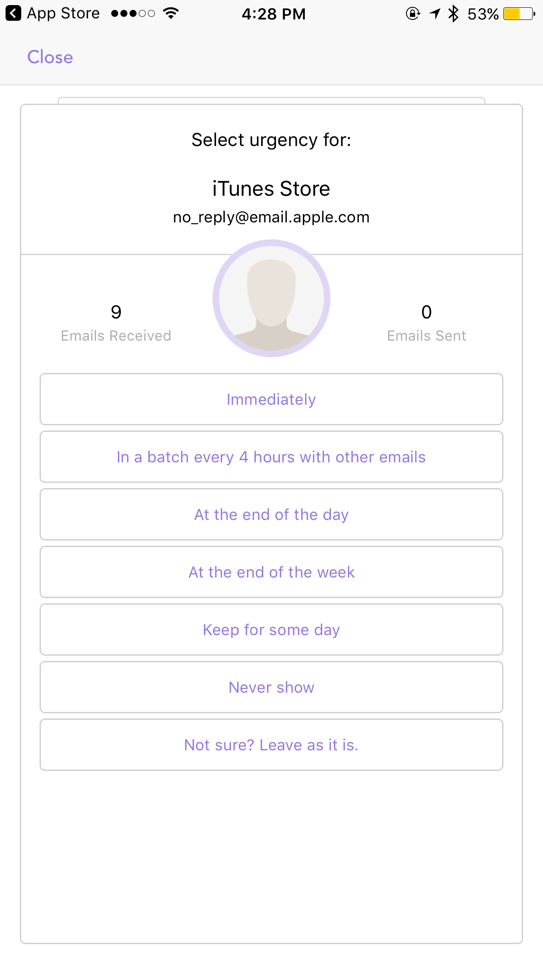

Example of instructions users were given

Example of prompt to set rule by each sender

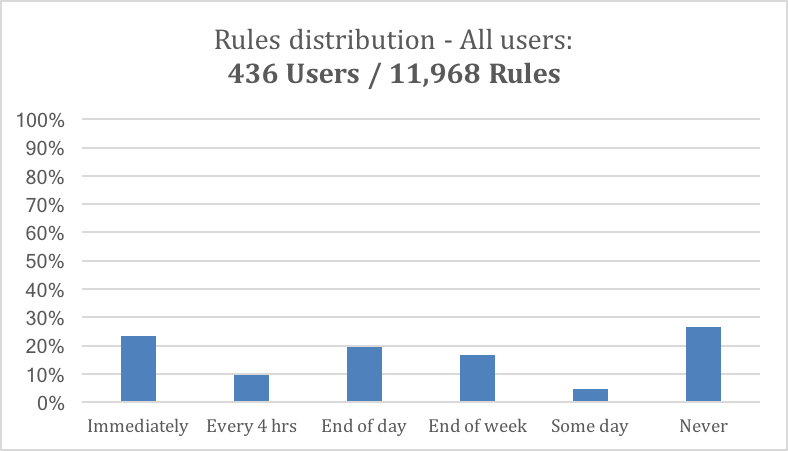

What did we find? People proceeded to create rules based on senders. Similar to our initial findings, only 23% of emails were set up to be in the “immediate” category. 10% were relegated to the every-4-hours category, 19% to the end of the day, 16% to the end of the week, 5% to some day and a whopping 27% to the “never” category.

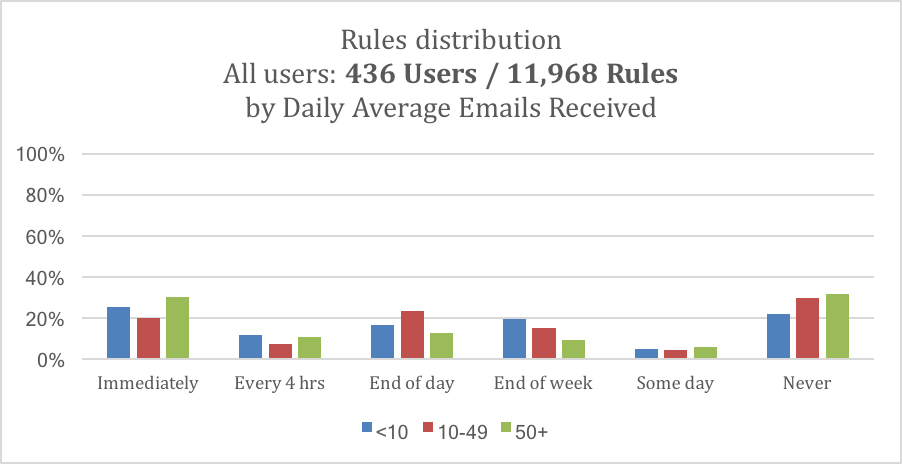

We also looked at whether people who received high vs, low quantities of emails behaved differently. While on the whole they had similar behavior, one interesting point of note is that people with 50+ emails/day put highest number of emails into “immediately bucket” (30%) vs. 10-49 emails/day (20%) and <10 emails/day (26%).

Overall, the key point and opportunity we should take away from all of this is that a very simple mechanism can have an impact, creating a significant amount of benefit for people. If you’d like to try this app for improving your email process for yourself, you can download it here.

[1] http://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Email-Statistics-Report-2015-2019-Executive-Summary.pdf

[2] Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Paper presented at the 107-110. doi:10.1145/1357054.1357072

[3] Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2006). The restless mind. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 946–958. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.946

[4] Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Paper presented at the 107-110. doi:10.1145/1357054.1357072

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I know that people are more likely to make smart decisions—about, say, contributing early and often to a retirement savings fund—if they’re nudged into it by default settings. How powerful is this effect? Do defaults push people a bit or change their choices dramatically?

—Tom

You’ve put your finger on one of the key findings of behavioral economics. Shlomo Benartzi and Richard Thaler, among others, produced probably the field’s greatest success by encouraging employers to create retirement benefits packages whose default options are set for savings. Such packages used to require employees to enroll if they wanted to start saving. By switching the default, so that employees were automatically enrolled and had to act if they wanted to stop putting aside money, saving rates increased dramatically.

But what effect does changing the default setting have compared with other incentives to save? Take a recent study by Michael Callen, Joshua Blumenstock and Tarek Ghani. They worked with Roshan, a mobile communications provider in Afghanistan, to create a savings plan for its 1,000-person workforce. Half the participants were given a default of “opt in” (and had to call to leave the plan), and the other half was defaulted to “opt out” (and had to call to start saving).

The researchers wondered how much changing the company’s matching level and the employees’ default settings would increase savings. They found that automatic enrollment had about the same effect on participation as providing the pricey incentive of a 50% matching contribution from the firm. Default settings, they concluded, are powerful indeed—perhaps not enough to make businesses stop matching contributions for their workers, but more than enough to make them sweat the default details.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

On vacation in Mexico, I saw a hardworking server waiting on guests at a resort—who didn’t leave a tip. I can’t imagine they would have behaved this way in our native Canada. Did the fact that they had purchased an “all-inclusive” vacation have anything to do with it?

—Kevin

Several forces were probably at work. First, some all-inclusive vacations aren’t clear about tips, which may incline us to think gratuities are covered. Second, remember the saying: “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.” When we travel, we become slightly different versions of ourselves—and can act more freely without tainting our own reputations, at least in our own eyes. Finally, immorality often stems from our ability to convince ourselves that we’re doing something OK—even if we know that we’d want people to behave better if we were on the receiving end.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m often flummoxed by long restaurant menus, so I’ll pick a familiar dish—and feel that I haven’t gotten the most out of my dining experience. Any dining advice?

—Tom

Trying new things makes life more interesting, but the fear of making mistakes can drive us to play it safe. Restaurants are great places for a risk. The most you can lose is one meal, and you can always ask for something else if you hate your adventurous dish (just tip well). So I often ask the waiter for the most unusual dish on the menu.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I work with liberal arts college students, many of whom don’t use their school’s career services early enough, if ever. What’s the best way to get reluctant students to participate in early career-discovery activities? Is there any way to make this fun or at least less overwhelming?

—Lisa

One of the challenges here is the perennial problem of “now versus later.” “Now” is at the forefront of our minds, and college students are no exception: What am I going to major in, how can I finish this 30-page paper on time, how can I balance basketball practice with my work-study job? All of these academic, social and financial concerns create cognitive demands right now—and make it hard to focus on career planning, which students tend to think about as years away.

You aren’t likely to convince busy and distracted students to assign a higher priority to the distant future. Instead, you could try to create structures that make career exploration feel like a “now” concern. Could a course require students to interview alumni in related fields at the career center? Could students fulfill certain distribution requirements by visiting the career center each semester? Could the career center pitch its services as tools to help students find summer jobs and internships?

Don’t present the career center as an optional, supplementary service to help find jobs after senior year. Try to match it to students’ immediate needs.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Uber infuriates me every time it declares “surge pricing.” I know that behavioral economics teaches us that framing is important. Would Uber be better off using the term “discounted pricing” during off-peak periods and “regular pricing” during peak periods?

—Paul

Yes, framing matters a lot. If Uber had its own fleet of cars and was just selling rides, your suggestion would be a great way to limit their customers’ ire. But Uber doesn’t have cars of its own and relies on motivating drivers to show up and offer rides. The same “surge pricing” that angers you appeals to Uber’s drivers, helping the company to get more of them on the road when it needs them.

The ideal framing would be to have Uber call its higher fares “surge prices” for its drivers and “regular prices” for its passengers—but that is manipulative and deceptive, so I wouldn’t suggest it.

As a message to customers, “surge pricing” also compels us to take immediate action. Imagine that you open the app and see that the current price is 1.5 times the usual fare. Do you wait and try again later, or do you worry that the price might leap up to 1.8 times that fare and order your Uber immediately?

Our deep desire to avoid regret—staring at a screen, stranded, as we watch prices soar—is so strong that it usually gets us to press the button even faster. So while customers hate surge pricing, it has important benefits for Uber.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

After a recent date, I’ve been wondering whether I should sign my next text to her with the word “love” or with an emoticon of a heart. Which one is she likely to take more seriously?

—Deb

Emoticons are a wonderful, colorful, rich way to express ourselves. But because emoticons can be interpreted in multiple ways, they are a less clear form of communication. So don’t hide behind the ambiguity of the emoticon. Use the word.

Love,

Dan

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Or, better yet.. would you be willing to help me out for free?

I’ve put together a quick non-academic questionnaire: Click here to take the survey

Your response will help me immensely in figuring out which route to take in an upcoming project. Thanks very much in advance! I appreciate everything you do.

Irrationally Yours,

Dan Ariely

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Do you have any tips to improve productivity?

—Shana

Here’s one: Pick a food or drink that you love, turn consuming it into a ritual and make working on an important long-term project a condition of indulging in this exciting consumption.

I adore my morning coffee, so I’ve transformed it into a daily ceremony by using the same mug, savoring the grinding of the beans, watching the coffee pour from the machine and smelling the aroma as it spreads throughout the room. I then take the cup to my office, sit at my desk and move to the important part: I connect this marvelous mug of coffee to a continuing task that matters deeply to me.

This can be an academic article, grading my students’ term papers or anything else that I want to do in principle but tend not to feel like doing on any given day. I allow myself to start sipping my coffee only after I’ve been working on the project for a few minutes, and I don’t stop working until I’ve drained my cup. (This works better with a big mug of coffee than with an espresso.)

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I love using behavioral economics to produce better decision-making. But what happens when people discover that they’re being manipulated to do something? Do they lose motivation or try to play against the system?

—Sebastian

Of course, if we found out that someone had deliberately deceived us into doing something against our best interests (such as signing up for an insurance policy we don’t need), we’d be upset. The more interesting question: How would we react if we found out that we had been manipulated into doing something that is in our long-term interest (like saving more or eating better)?

Recent research found that in such cases, it doesn’t matter if people find out that they were manipulated. This holds across many domains, whether it is influencing people to eat healthier food, getting them to fill out advance directives about what to do if they become too ill to express their wishes, or prompting them to donate more to a charity. So while it might seem morally dubious to manipulate people into following their best interests, they are generally OK with it.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Is love overrated? I am deeply in love with someone, but to be with them, I’ll have to change jobs and cities. Should I make these changes and hope that this love will last, or should I assume that this love, like most loves, is doomed to fade and not worth the risk?

—Amy

Wait a few months, and if you still feel as ardent about your partner, take the chance. In general, the odds are very much against us when we start almost anything: a business, a book, an exercise regimen. But we often encourage people to do these things anyway, so why not for love? The odds are low that your love will burn as brightly in 10 years, but some risks in life are worth taking.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Some restaurants have made news recently by eliminating tipping. But will the long-term effect be worse service?

—Phil

I wouldn’t expect a decrease in the quality of service. I’m not sure that tipping is a particularly motivating reward to begin with. For one thing, tips in many restaurants are often pooled among employees. That means that the gratuities are averaged across workers, so individual waiters won’t immediately or strongly experience the benefits (or punishments) that stem from superb or lousy service. Furthermore, statistical modeling by Ofer Azar of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev found only a small relationship between tips and service quality. He concluded that other factors had more influence on the type of service that you’re likely to get.

If anything, I suspect that eliminating tipping and giving waiters a stable, living wage would improve the quality of service. Without the vagaries of tips, restaurant employees would have a consistent, dependable income—and, perhaps, higher job satisfaction. That would help lower employee turnover and raise profits for the restaurant. These are all fine reasons why more restaurants should get rid of tipping.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve found that the most interesting people to talk to are often obsessed with a topic, whether it is food, music or economics. How can I increase my likelihood of meeting this type of person? What questions can I ask to uncover people’s passions when I meet them?

—Riley

When we meet someone new, most of us have a puzzling tendency to start the conversation as if we are exchanging resumes. We typically don’t go beyond questions like “What do you do?” and “Where are you from?” But the key to a good conversation isn’t meeting the right type of person; rather, as you suggest, the trick is asking questions that allow almost anyone to reveal who they are, what they have experienced and what they are passionate about.

Often, the questions that can help put a bit more depth into our conversations are more complex than the standard “What do you do” approaches. They also require more openness, effort and daring from the person asking the questions. Think of asking new friends about their ideal dinner companion, living or dead, or about the heroes they most admire or about the aspects of their life for which they’re most profoundly grateful. It may be a little unfamiliar, but such questions do get conversations going in very different directions.

I know from personal experience that starting conversations by asking nonstandard questions isn’t always easy. But as you get more used to asking such questions, your discussions will become more interesting. We all want lives filled with meaning, so we should get beyond the default of vacuous conversation-starters.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently learned about the Stockholm syndrome, in which captives develop sympathetic feelings for their captors. I know that the parallel isn’t exact, but does this dynamic operate in marriages too, with both partners (in a metaphorical and emotional sense) seeing themselves as imprisoned in a way and the attraction to the person “capturing” them creating a stronger relationship?

—Abhinav

Sorry, but the Stockholm syndrome just isn’t a sensible way to think about marriage—not least because marriage lacks the glaring power difference between the person doing the capturing and the person being captured. But now that I think about it, maybe the syndrome is a good way to think about spending the holidays at your in-laws, and perhaps this glue helps keep families together during those trying times.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Yesterday, I lost my phone in the woods and spent hours looking for it. Many hours later, with the help of my mother and the “Find My iPhone” app, we found it in the snow. It was a lot of effort—the hardest scavenger hunt we’ve ever been on—but I’ve never had so much fun or appreciated my phone as much as I did that day. I know that, in general, making a major effort leads people to love something more when they create it (as you have argued with the “IKEA effect”). Does this principle apply to finding a lost item too?

—Niv

Yes. Our appreciation for an item isn’t just about creating it; it is also about the connection we make with it. Every time you invest effort in some object (as in your hunt in the woods), you strengthen your link with the item, and you like it more.

But before you start losing items on purpose, let me point out two limits to your exciting discovery. First, the joy and increased attachment that you experienced was probably yours alone. I can’t imagine that your mother felt the same affection for your phone after rooting around in the snow. Second, the surge of fun and fondness about this particular item isn’t something you’d want to experience multiple times a year—so hang on to your phone.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve been reading that chain restaurants with many branches are now required to post calorie information. Do you think this will push people to eat better or not?

—Paul

Probably not. The experiments that we’ve done on the impact of this sort of calorie information on eating behavior have shown scant effects on what people order. There seems to be a gap that prevents us from translating knowledge into action, and just giving people the data clearly doesn’t do the trick. People often tell me that knowing a menu item’s calorie count influences their ordering, but the research data on this suggests that such effects are very small at best.

There may also be a downside to posting the calories: We know that the presence of “healthy” side dishes can make people feel entitled to order “unhealthy” entrees. Darren Dahl and his colleagues have shown, for example, that the simple presence of a healthy item on a menu increases the likelihood that customers will order the least healthy options. The basic principle is called “licensing”: When we do something that we think is good (like ordering a small salad), we feel that it balances out a subsequent “bad” action (like eating a double cheeseburger).

Given these findings, I predict that we will see more calorie listings on menus, with more items such as side salads as healthy options. People will order these salads—often with gloppy and highly caloric dressing—and continue eating other high-calorie items. Don’t expect it to help our waistlines.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Is regifting OK? Over the years, I’ve received plenty of gifts that I didn’t want, and I’m thinking about getting rid of them this holiday season. Can I tell the people that I’m regifting what I’m doing?

—Beth

In general, I consider regifting a wonderful practice. So long as the present that you are regifting is something that you think the new owner will appreciate, you aren’t just giving them something that they will like; you are preventing waste and saving money.

As to whether you can tell your friends and family that you’ve regifted them a present, sadly, we still aren’t a sufficiently enlightened society. So for now, I would slap on fresh wrapping paper and keep the history of the gift a secret.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I always agonize this time of year over getting the right gift for my children’s teachers. I hate gift certificates, which feel so thoughtless and generic. So what should I give?

—Raquel

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

As we enter December, I wonder whether I should make any New Year’s resolutions. I have been making them for years, and I inevitably fail to keep them, which is pretty frustrating. Should I give up or give it another go?

—Jamie

Don’t give up. Even if you stick to your resolution for, say, three or six months, you will be better off than you would have been if you had done nothing. And you might do better if you make New Year’s resolutions that are more limited and achievable. For example, what if instead of promising yourself that you will exercise three times a week for the whole year, you pledged just to work out for six weeks? That goal would be far easier to grasp, and maybe by the time you reach it, you will want to keep going.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like