Recent Interview – Motivated Employees and Company Value

I recently spoke with Observer about the impact motivated employees can have on a company’s value. We discussed some of the background laboratory and industry research, looking in the data for signals that predict returns in the stock market, and what our findings mean for very large companies. We wrapped up with some thoughts about whether working from home is helping employees in the long-term.

From the interview:

Observer: Let’s start with discussing how you came to found Irrational Capital

Ariely began by explaining the trajectory of his career, which began with testing motivation in laboratory settings, then working directly with companies to design systems to better motivate their employees.“And the third stage, which is the stage we’re talking about now is saying, what about all the other companies out there? It started from an academic question of, could I find signals that could predict excess return in the stock to the stock market. The first exercise was to go and get data. So I spent years trying to collect data and my data has some private data and some public data. It’s a mix of the two but essentially you can think of it as a combination of satisfaction surveys and what’s on LinkedIn and what’s on Glassdoor and, and so on,

And then the question from all of this data, is what would predict returns from the stock market? What would not? And I didn’t start it like a black box approach because I already had the academic knowledge of what seems to be working from other studies and from my own studies. So for example, do companies that pay higher salaries have higher returns? The answer is no. But it turns out that the perception of fairness of salary matters a lot. So the absolute level of salary doesn’t matter so much. The relative salary matters a lot.”

Read the original article on the Observer website here.

What gives you your #MondayMotivation?

When work can give you that Friday Feeling…

Which of these pictures best reflects your job?

Love, status, money, or morals?

Better (and more) Social Bonuses

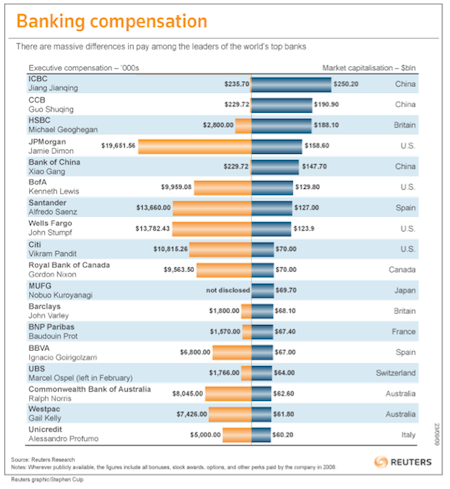

Over the last few years, many individuals (myself included) have been feeling tremendous anger about the level of executive compensation in the US, an anger that is particularly strong against those in the financial sector. As you can see in the chart below, there is an incredible gap between CEO compensation in the US compared to most other countries. Bankers are paying themselves exorbitant wads of cash, seen in both in their salaries and bonuses. And in their defense, the bankers in question claim that such extravagant wages are essential to properly motivate them, and that without such motivation they would just go and find a job somewhere else (they never exactly specify which jobs they will get and who will pay them more, but this is another matter).

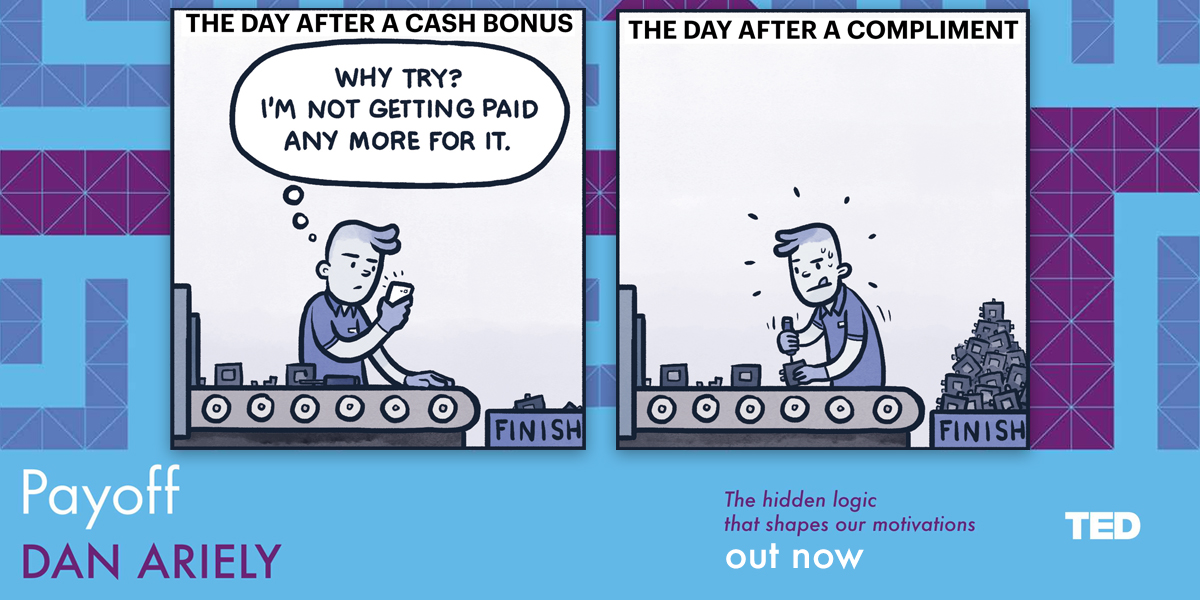

Inordinate compensation levels aside, it is important to try and figure out more generally how payment translates into motivation and performance. There is a general assumption that more money is more motivating and that we can improve job performance by simply paying people more either in terms of a base salary, or even better as a performance-based incentive – which are of course bonuses. But, is this an efficient way to compensate people and drive them to be the best that they can be?

A new paper* by Mike Norton and his collaborators sheds a very interesting light on the ways that organizations should use money to motivate their employees, boost morale and improve performance – benefiting both employees and their organizations. The researchers looks at a few ways that money can be spent and how that affects outcomes such as employee wellbeing, job satisfaction and actual job performance. Specifically, they examine the effect of prosocial incentives, where people spend money on others rather than themselves, and they find that there are many benefits to spending money on others (think about the inherent joy of gift-giving).

In the first experiment, the researchers gave charity vouchers worth $25 or $50 to Australian bank employees and asked them to donate the money to a charity of their choice. Compared to people who did not receive the charity vouchers, those who donated $50 (but not $25) claimed to be happier and more satisfied with their jobs.

The second experiment took the concept of prosocial incentives a step further by directly comparing people who were asked to spend money on themselves (a personal incentive) with those who were asked to purchase a gift for a teammate (a prosocial incentive). This experiment took place in two different settings — with sales and sports teams — and looked at a broader range of outcomes. It not only examined employee satisfaction, but also the other side – benefits to the organization in terms of employee performance and return on investment. While neither sales nor sports teams improved when people were given money to spend on themselves, Norton and his colleagues found vast improvements for those who engaged in prosocial spending. While they were purchasing a gift for a teammate, they also became more interested in their teammate and were happier to help them further in multiple other ways.

If we compare these experiments, we can also see that while a gift of $25 did not make a difference when it was donated to a faceless and impersonal charity, a gift of $20 provided numerous positive outcomes when it was given in the form of helping out a teammate. Thus, it appears that we can reap the greatest benefits when we spend money on others, and even more when we spend money on close others.

Taken together, these results also suggest that our intuitions are leading us down the wrong path when we assume that we will be happiest and most motivated when we earn money to spend on ourselves. The findings from this paper can be extended to recommendations for current business practices, particularly in cases where compensation is very high. In fact, Credit Suisse has gotten a head start on adopting the idea of prosocial spending, as it has recently implemented a program requiring its employees to donate at least 2.5% of their bonuses to charity. Now, is this just a PR trick to try and diffuse some of the anger that people feel these days about bankers, or is this a real effort to increase and improve motivation? I don’t know. But what is clear to me is that prosocial incentives, either in the form of charitable donations or team expenditures, can be an effective means of encouraging more positive behavior for the individual, their teammate and for society.

* Norton MI, Anik L, Aknin LB, Dunn EW & Quoidbach J (manuscript under review). Prosocial Incentives Increase Employee Satisfaction and Team Performance.

Why we care? The Gulf & the Amazon

There are a few topics that Mother Teresa and Joseph Stalin agreed on, other than the cause for human apathy. So I suspect that both would be surprised – as I am — about the reaction to the BP oil spill.

If six months ago someone were to describe to me a tremendous oil spill and ask me to predict our collective reaction to it, I would have said that we would be highly interested in this disaster for a week or two and, after that short time, our interest would dwindle to “mildly interested.” After all, we (the public) appear only vaguely interested in a whole slew of environmental issues. The destruction of the Amazon rainforest, for example, has been going on for decades. Since 1970 we’ve managed to destroy about 600,000 square miles (www.mongabay.com/brazil.html), but we’re so used to these kinds of statistics that no one seems to care much.

So, why is it that we care so much about the BP oil spill than what happens on a daily basis in the Amazon? Here’s what we know about human caring and compassion. First and foremost, it is based on our emotions rather than our reasoning. Joseph Stalin said, “One death is a tragedy, a million is a statistic.” Mother Teresa said, “If I look at the masses I will never act, but if I look at the one I will.” In oil spill terms: We see pelicans and turtles mired and dying in oil, and we want to cry. We hear about families who have had their homes ruined and their livelihoods horribly affected or even destroyed, and we sympathize with their helplessness and want to do something to help them recover. Our compassion isn’t necessarily proportional to the magnitude of the catastrophe. It depends on how much of our emotion is invoked.

Perhaps I’m mistaken about human apathy, but it is also possible that there are particular features of the BP oil spill that influence how much we care, and that if these features were different, we would care substantially less, even if the magnitude of the disaster were the same.

Here are a few characteristics that might differentiate the BP oil spill from the destruction of the Amazon. First, it is a singular event with a precise beginning. Second, while the tragedy was ongoing (and we are not yet sure if it has ended or not) it seemed to become more desperate by the day. Third, we have a single organization that we can villainize. In contrast, in the Amazon, there are many organizations and individuals at fault, both in the countries where deforestation is occurring and abroad. And fourth, the Gulf is so much closer to home (at least for Americans).

The BP oil spill is, of course, a hugely devastating tragedy. At this stage, we don’t fully understand the magnitude of its consequences, which will likely last for decades. At the same time, it might be worthwhile to take this moment in history as an opportunity – when are caring about this tragedy is still high – to reflect on our larger relationship with the oceans, and the apathy with which we generally greet the less dramatic, but perhaps equally devastating, environmental consequences of overfishing and “everyday pollution.”

I suspect that, because our abuse of the oceans is commonly the result of many small steps by many people, we fail to become enraged with either the process or the outcomes. But we should be. And we should do our best to take better care of our oceans, and not only when the pollution is caused by a single large, easily villainized organization.

Maybe this is another case in which we want to make sure that we don’t waste a really good crisis (for a related missed opportunity see financial crisis). Maybe it is time to look more broadly at our interactions with the oceans and make it a better long-term relationship, and maybe we need to do this while we still care, and before our interest in the oceans dissipates.

…

A talk I gave at PopTech

How to commit the perfect crime

There is a certain perverse pleasure in contemplating the perfect crime.

You can apply your ingenuity to the hypothetical issues of choosing a target, evading surveillance and law enforcement, dealing with contingencies and covering your tracks afterward. You can prove to yourself what an accomplished criminal mastermind you would be, if you so chose.

The perfect crime usually takes the form of a bank robbery in which the criminals cleverly bypass all security systems using neat gadgets, rappelling wires and knowledge they’ve acquired over several weeks of casing the joint. This seems to be an ideal crime because we can applaud the criminals’ cunning, intelligence and resourcefulness.

But it’s not quite perfect. After all, contingencies by definition depend on chance, and therefore can’t ever be perfectly thought out (and in all good bank-robber movies, the thieves either almost get caught or do). Even if the chances of being caught are close to zero, do we really want to call this a perfect crime? The authorities are likely to take it very seriously, and respond accordingly with harsh punishment. In this light, the 0.001 percent chance of getting caught might not seem like a lot, but if you take into account the severity of punishment, such crimes suddenly seem much less perfect.

In my mind, the perfect crime is one that not only yields more money, but is one where, if by some small chance you did get caught, no one would care, and the punishment would be negligible.

So, with this new knowledge how would you go about it?

First, the crime would need to be obscure and confusing, making it difficult to detect. Breaking a window and stealing jewelry is too straightforward. Second, the crime should involve many people engaging in the same type of crime so that no one can point a finger at you. This is why looting, though easy to detect, is much more difficult to get a handle on than a single robbery. Third, your crime will need to fall under the shady umbrella of plausible deniability so that if you do get caught, you can always say you didn’t know it was wrong in the first place. With this kind of defense, even if the public cares, the legal system may let you off easy. Moreover, plausible deniability allows you to apologize in the aftermath and ask forgiveness for your “mistake.”

If you really want to go all out, do something you can spin in a positive light, and maybe even create an ideology around it. This way you can then explain how you’re actually on the side of progress. Say, for instance, you’re “providing liquidity” and “lubricating the market” and thereby helping the economy – even if it happens to be by taking people’s money. You can also resort to opaque and promising-sounding language to make your case; you’re “restoring equilibrium,” “eliminating arbitrage” and creating “opportunity” and “efficiency” across the board.

Basically, just bottle snake oil and tell them it will cure, rather than cause, blindness.

Something to avoid, on the other hand, is anything involving an identifiable victim with whom people can sympathize and feel sorry for. Don’t rob one little old lady blind, or any one individual for that matter. It’s part of human nature that we care so much about blue-collar crime, even though the average burglary only costs about $1,300 (according to 2004 FBI crime reports), of which the criminal only nets a few hundred. Crimes like burglaries are the least ideal crime: they’re simple, detectable, perpetrated by a single or just a few people. They create an obvious victim and can’t be cloaked in rhetoric. Instead, what you should aim for is to steal a little bit of money from as many people as possible—little, old or otherwise — it doesn’t matter, as long as you don’t reverse the fortune of any one individual. After all, when lots of individuals suffer just a bit, people won’t mind as much.

So, what is the ideal crime? Which activity is difficult to detect, involves many people, has plausible deniability, can be supported by an ideology and affects many people just a bit? Yes, I think you know the answer, and it does involve banks…

Seriously, what we have here is a problem with our priorities. We have tremendous regulations for what is legal and illegal in the domain of possessions and blue-collar crime. But, what about regulations in banking? It is not that I really think that bankers plan and plot crimes for a living (I don’t), but I do think they are continuously faced with tremendous conflicts of interests, and as a consequence they see reality in a way that fits their own wallets and not their clients. The recent turmoil in the market is just a symptom of this conflict of interest problem, and unless we remove conflicts of interests from the banking system, we are going to be part of a long stream of perfect crimes.

This blog post first appeared on a website for a new PBS show called Need To Know

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like