Ask Ariely: On Lyrics, Joint Accounts, and Dialing Mom

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, just email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

The Korean music video “Gangnam Style” by the pop singer PSY has now been viewed on YouTube over a half billion times. Why do you think this video has become so popular? Most viewers don’t understand what PSY is singing about in Korean, yet they seem to love the video anyway.

I wonder if this is partially because the words are in a foreign language that they don’t have a clue about. It’s the same in my country, Kazakhstan. Although Kazakhstanis usually do not get the content of what they are listening to, they love American pop music and (these days) Korean pop. The closest parallel I can think of is when a woman wearing a miniskirt generates more curiosity than a woman who’s fully undressed.

Recently, PSY announced that his next debut will be in English. Would this be a mistake?

-Nurdaulet

A few years ago, Mike Norton, Jeana Frost and I looked at the question of ambiguity and found exactly the mechanism you’re suggesting—that knowing less can lead to higher liking. Focusing on online dating, we found that when people read online profiles of potential partners that were more ambiguous and imprecise, they liked the profiles more. That’s because when we face new information we try to resolve ambiguity, but rather than do it accurately, we let our minds fill in the gaps in an overly optimistic way. Sadly, we eventually meet the person behind the dating profile, and then our expectations get crushed (which, by the way, happens a bit more to women).

I just tried to understand the PSY phenomenon for myself (in an admittedly unscientific way) by watching 10 YouTube clips of popular songs (in English) without paying much attention to the words. Then I read each lyric carefully, twice. What I found is that the quality of the lyrics was surprisingly low, and this cut down on my appreciation of the videos, which I’d initially enjoyed.

What this suggests is that it might be good for the musicians to get people not to pay attention to the lyrics—maybe by creating very hectic music videos or by singing in a different language, or both. So if I were PSY, I’d switch to a language that almost no one understands—maybe Yiddish.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently got married, and my wife and I have been debating the topic of bank accounts. She’d like to combine them, because she wants to know how much is coming in and going out. I think separate accounts would be simpler for taxes, personal spending and budgeting. What’s your take?

-Jonathan

The fact that you’re wondering whether to follow your preferences or your wife’s tells me that you are either a slow learner or very recently married (sorry, my Jewish heritage would not let me pass up that opportunity). But to the point: I think you should have a joint account.

First, there’s no question that in reality your accounts are joint in the sense that anything one of you does has an effect on your mutual financial future. For example, if one of you starts buying expensive cars from your individual account, there’s going to be less money for both of you to spend later on vacations, medical bills and so on.

More important, by getting married you have created a social contract of the form: “I will take care of you, and you will take care of me.” Adding a layer of financial negotiations to this intricate relationship can easily backfire. Think about what would happen if there was “my money” and “your money”? Would you start splitting the bill in restaurants? What if one of you has an extra glass of wine? And what if your wife ran out of “her money”? Would you tell her that if she does the dishes and takes the garbage out for a week, you would give her some of “your money”?

The problem is that once money becomes intertwined with deep relationships, they can start looking a bit more like prostitution than like love, romance and long-term caring. Separate bank accounts do have some advantages, but having them could put unnecessary stress on your relationship—and your relationship is much more important than managing your money efficiently.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My son travels a lot and as a consequence we don’t talk much. Can you suggest a way that I can talk to him more frequently?

-Yoram

I suspect that your son has a busy life and that his lack of calling does not reflect his love or caring for you. This said, maybe you can pick a regular day and time to talk, and this will make your conversations more likely. And I promise to call you and mom the moment I get back from South America.

Love, Dan

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Why Can’t We Be Friends? The Joy of the Political Fight

Journalists, businesses, comedians, and the rest of us have been crying out to politicians, “Why so much fighting?” and asking, “Can’t we all just get along?” Despite these calls for bipartisanship and peace in Washington, the quarrels rage on. Why?

Although politicians say they wish the fighting would end, they may actually take pleasure in the brawl. It may be emotionally rewarding for partisans to be in the “smarter” and “morally superior” party.

Psychological research shows how derogating members of other cultural groups can make oneself feel superior and can even increase one’s self-esteem.

This may explain why partisans’ lives are so often full of tweeting, Facebooking, and protesting about how other parties are terrible. Such actions may be motivated more by the desire to immediately improve their self-esteem and feel self-righteous than by the desire to improve policy.

For instance, many liberals tweet claims that conservatives do not care for the poor. One explanation for this could be that liberals really do care for the poor, but they may also tweet this because it makes them feel better to be the good guy fighting for the poor compared the conservatives that they claim are evil and selfish.

Because viewing the other party as evil can make oneself feel better by comparison, partisans might actually want the other party to be evil. Conservatives may actually want Obama to be a communist and liberals may actually want Romney to be universally against women’s rights. These claims fit the self-flattering good versus evil narrative, where the opposing party is the Evil Empire and the partisan’s own team is the heroic Rebel Alliance fighting for good.

So when we ask the question, “Can’t we stop the fighting?” The answer seems to be, “No, the self-righteous fighting is too much fun!”

~Troy Campbell & Rachel Anderson~

Ask Ariely: On Planning Ahead, Halloween Rationing, and Flipping Coins

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, just email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m shopping for several plane tickets for personal trips over the next couple of months, and I keep running into the same problem: “Current me” wants to pinch pennies by choosing overnight flights, routes with several legs or inconvenient airports that would require me to drive a few hours out of my way. “Future me”—the one that actually has to pick up the rental car at 11 p.m. and drive two hours from Phoenix to Tucson the night before a friend’s wedding—sometimes resents that I wouldn’t just spend an extra $100 to make an already expensive trip more pleasant. Travel-booking websites are getting better and better at predicting what will happen to flight prices, but I don’t seem to have gotten any better at predicting my own preferences.

How can I best determine whether these savings will feel worth it to me in the future? Or, failing that, how can I console myself when I’m pulling into a Tucson motel parking lot at 1 a.m.?

—Ruth

Your framing of the problem is spot on. In your current “cold” state, you focus on the price, which is clear and vivid and easy for you to think about. When you actually take the trip, that version of you will be feeling exhaustion and need for sleep (a “hot” state), which will be very apparent to you at that point—but it is not as vivid right now.

This, by the way, is a common problem that arises every time we make decisions in one state of mind about consumption that will take place in a different state of mind.

Here is what I recommend. In order to make a better decision, tonight at 9 p.m. put in some laundry and spend the next two hours sitting on the washer and dryer (this is to simulate the fun of flight, and if you want to really go all out, supply yourself with a package of peanuts and a ginger ale). When you “land” at 11 p.m., look around for some missing socks (to simulate looking for your luggage) and then, properly conditioned to think about the actual trip, log into the travel website and see what is more important to you: saving a few bucks or getting to bed sooner.

Plus, imagine how you would look in the wedding pictures after a long night of uncomfortable traveling.

Good luck in your decision and “mazel tov” to your friend.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I was wondering how you allocate candy during Halloween to make sure kids don’t dishonestly take more than they should. I’ve thought of handing each of the children their candy, but that way the kids can’t pick what candies they like best. Also, this method takes more time, which I don’t have, and makes things less pleasant for me.

But if I leave a bowl of candy out without any oversight, I know what will happen: They’re all going to take more than their share until the bowl is empty.

—Mary

Beyond Halloween, this is a general question about honesty. One of the things we find in experiments on honesty is that if people pledge that they will be honest, they will be—and this is the case even if the pledge is nonbinding (or what is called “cheap talk”).

Given these results, I would set up a table with a large sign reading “I promise to take only one piece of candy [or whatever amount you want them to take] so that there is enough left for all the other trick-or-treaters.” Below the sign, place a sheet of paper for your visitors to write down their names (and, given that it is Halloween, use red paint and ask them to sign in “blood”). With this promise to take only one candy, the public signature in blood and the realization that if they take more candy they will deprive their friends of having any, I suspect that honesty will improve dramatically.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Do you have general advice for how to approach difficult decisions? I’ve been thinking about which car to get for a very, very long time, and I just can’t decide.

—John

The poet Piet Hein gave this sage advice some time ago, and I think it will work in your case:

“Whenever you’re called on to make up your mind

And you’re hampered by not having any,

the best way to solve the dilemma, you’ll find,

is simply by spinning a penny.

No—not so that chance shall decide the affair

while you’re passively standing there moping;

but the moment the penny is up in the air,

you suddenly know what you’re hoping.”

Truth Bending: Why Politicians are Such Comfortable Liars

Today many Americans find themselves thinking: how are politicians so comfortable lying?

The answer may be found in the important element of how they lie. Specifically, politicians rarely lie straightforwardly; instead, they bend the truth. Because “truth bending” is rooted in some version of the truth, it creates enough wiggle room for politicians to maintain the belief that they are good, honest people.

Moral psychology shows that people lie to the extent that they can still see themselves as good people. Their wrongful or shady actions need to allow enough wiggle room such that they do not perceive themselves as bad, and truth-bending conveniently provides this flexibility.

Most of the popular 2012 elections lies are examples of truth bending. When we examine this component, we can better understand why politicians feel so comfortable making false claims. Let’s take a look at two of the most popular bends.

“The 47 Percent” Attack Ads

Obama for America ads use the 47% comments to say Romney doesn’t care about veterans, the elderly, and at least 47% of the country.

The Truth:

Romney commented in a discussion of his campaign strategy, “My job is not is not to care about … the 47%.” However, he did not mean that he did not care about these people nor did he state that he does not want their lives to be improved. Instead, Romney meant that he would not focus on courting these voters because he believes that those efforts would be a waste of the Romney campaign’s time.

“You didn’t build that”

The Bend:

The Romney campaign publicizes the following quote from Obama: “If you’ve got a business—you didn’t build that.” This quote is used by the Romney Campaign to express that Obama does not think that businesses build themselves and instead rely completely on the government to succeed.

The Truth:

Obama stated that, “If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business—you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen.” In this quote, Obama expresses his belief that government can help create the environment that permits businesses to thrive. Obama says businesses did not build the roads that the businesses use. He does not claim people didn’t build their own businesses.

Jonathan Haidt explains in The Righteous Mind that when people want to do or believe something, they ask themselves, “Can I do this?” and search for an argument to support their desired actions.

Thus, when deciding whether an action is morally permissible, people have to convince themselves that it is. Without enough wiggle room, people cannot always rationalize their actions. However, as in the examples above, the combination of three factors create enough wiggle room for the campaigns to carry out such truth bending.

1. There is a bit of truth in the lie. These bends are grounded in direct quotes, or what high school students would call “primary evidence.” A politician may feel morally wrong putting words in another politician’s mouth, but taking the words that another politician said out of context may feel less wrong.

2. The essence of the message is true. Even if politicians realize they are bending the truth, technically, they may believe that they are still expressing the truth. The Obama campaign believes Romney only cares about the individuals at the top and the Romney campaign believes that Obama doesn’t care for individualism or the private sector. Their political ads may distort the truth of an isolated statement, but they also believe that the ads communicate a larger truth about the other candidate.

3. Both firmly believe they are the good guy fighting for the world. When people believe they are doing something altruistic (e.g., helping a family member), their wiggle room (and, consequently, their dishonest behavior) grows. Since politicians believe they are fighting for the good of the entire world, their wiggle room is proportionately greater.

A final caveat. One view may be that politicians are intentionally lying as much as possible and only curbing their lies out of fear of media scrutiny. Though the media does play a role in curbing bends, a richer understanding of the 2012 election comes from understanding politicians as somewhat normal moral beings who are in the perfect situation to bend the truth.

~Troy Campbell and Rachel Anderson~

Partisans Don’t Know How the Middle Feels

Ten minutes into the Presidential debate, my democratic friends were sure it was a failure. They tweeted, “Nothing he is saying is making me feel anything.”

A lot of Democrats have walked away from Romney’s monologues unaware of how moving Romney’s comments can be. They have felt absolutely secure that an Obama victory is in the bag. They have assumed that because they did have not found Romney’s words exciting, no one else would either.

However, Democrats were never going to feel excited by a Romney-Ryan speech. And if these Democrats gauge Romney-Ryan’s success by their own feelings, they’ll never understand how well the Romney-Ryan is doing with the electorate. Yet, people consistently make this mistake and predict that others’ reactions will be the same as theirs. When people do this, it leads them, their businesses, and their political parties to be overconfident about their lead in the market place

This inability to predict how different people will react can be costly for individuals, political strategists, and businesses. Should an Apple product designer predict the success of a Microsoft product based on how unimpressed she herself is? No. Should a bleeding heart liberal use her own outrage about Romney’s 47% comment as an estimate of how Republicans will react? No. Should a social conservative use his feelings about President Obama’s comment about Americans clinging to God and guns? No.

With the vice-presidential debates happening tonight, I am confident that partisans on both sides will think that the other failed to emotionally connect with the electorate. The truth however is that partisans cannot emotionally connect with each other.

~Troy Campbell~

Real-world Endowment

One of economists’ common critiques of the study of behavioral economics is the reliance on college students as a subject pool. The argument is that this population’s lack of real-world experience (like paying taxes, investing in stock, buying a house) makes them another kind of people, one that conceptualizes their decisions in altogether different ways. And although many decision-making studies in behavioral economics have shown that young adults do not act much differently than adult adults when it comes down to their core behavior (think of MDs whose diagnoses are influenced by defaults and the framing of choices, for example), the argument persists as a sweeping dismissal of using students as the main testing ground.

One area where we can test this assumption is with the endowment effect. Simply put, the endowment effect shows that we value the things we own more than identical products that we don’t own. This causes a mismatch between buyers and sellers, where buyers are often willing to spend less than the seller deems an acceptable price.

If we are to assume that consumers hold constant, well-defined preferences, this puts the stability of valuations into question. As such, the endowment effect has puzzled economists for quite some time because in principle, valuations should not be affected by ownership; if a purple hat is worth $15 to you, it should be worth $15 to you whether or not you have purchased it, and this value should remain consistent both before and after you purchase it.

Let’s say that undergraduate A receives a mug and is asked how much money she would require to sell it to undergraduate B. Studies find that undergraduate A will have a much harder time parting with the very same mug that undergraduate B has no attachment to. Now, these students don’t have much experience with real-world markets. So the question is — would those who do have experience in these markets behave differently than their inexperienced undergraduate counterparts?

In his senior research paper, Sean Tamm studied exactly this*. He approached 30 car salespeople and 46 realtors, a population that presumably has much experience with negotiating their maximum willingness to accept (when selling items), as well as with a maximum willingness to pay (when purchasing items). He endowed half of these participants with mugs, and asked the sellers what it would take to sell the mugs and the buyers what it would take to buy the mugs. And despite the extensive real-world market experience of these participants, willingness to accept was about three times higher than willingness to pay, demonstrating that even expert negotiators are susceptible to the endowment effect. This is consistent with previous research, showing an overvaluation of owned goods of about 2.5 times that of unowned goods.

This is just one more example of real-world experience not playing the protective role that we often assume comes with experience. It also suggests that our brains and the way we make decisions are similar, and that for the most part, students are operating under the same constraints as those with much more experience. In the end, we may just have to accept that students are real people (most of the time).

*“Can Real Market Experience Eliminate the Endowment Effect?” by Sean Tamm, Stetson University

Ask Ariely: On Splitting Checks, Vacations, and the Internet

Here’s my column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, just email them to askariely@wsj.com

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

In your answer last week about splitting checks at restaurants, you noted that there is a “diminishing sensitivity as the amount of money paid increases.” I’ve noticed this in my own spending. I’ll go out of my way to save a buck and then spend an ungodly sum on some purse. Why is that? And how can I control it?

—Lembry

Diminishing sensitivity is a very basic way that our minds work across many domains of life. For example, imagine that you light up one candle in the middle of the night. This small amount of light will dramatically change your ability to see your surroundings. But what if you already have 10 lit candles and you add one more? Now it would not have much of an effect. The basic idea of diminished sensitivity is that our minds tend to register relative increase; we take any additional amount of stuff as if it were a percentage gain, not an absolute one.

Now, when it comes to money, we should think about it in absolute terms ($10 is $10 regardless of whether we are saving it from a dinner bill or from the price of a new car), but we don’t. We think about money in terms of percentages, too.

What can we do about it? It’s not easy, but we should try to fight this natural tendency. One method that I use from time to time is to take the amount of money that I am thinking about spending and ask myself what else I could get with it. For example, since I like going to the movies (and let’s say that the price of two tickets and popcorn is $25), I ask myself whether a given $25 of spending on a prospective purchase is worth more or less than the pleasure of going to the movies.

When framed this way, it doesn’t matter if the savings come from a dinner bill or a new computer—and it helps me to ask the question “What would I enjoy more?” in a more concrete way. So, the next time you are shopping for a new purse, try to measure its price in terms of another use for that money that you might value more.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have been on vacation for the last few days in New York City, and while reading your most recent book, on dishonesty, I have been wondering whether people behave more or less honestly on vacation.

—Julie

This is an interesting question, and (sadly) I don’t have any data to share with you on this topic. But here are a few ideas to consider:

Why might people on vacation be more honest? While on vacation people seem to be more relaxed with spending money, which suggests that the motivation to be dishonest for financial gain might be lower. On top of that, people on vacation are more often in a good mood, which they might not want to spoil by behaving badly.

Why might people on vacation be less honest? On vacation, the actions we take are in a new context. As they say, “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.” Also, the rules on vacation might seem less clear: What are the regulations for parking in San Francisco? How much should you tip in Portugal? Is it OK to take the towels from this hotel? This sort of wishful blindness can make it easier for us to misbehave while still thinking of ourselves as generally wonderful, honest people.

On balance, then, are vacationers more or less honest? I suspect that they are less honest—but I would love to be proven wrong.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What is it about Internet communication—Facebook, Twitter, email—that seems to make people descend to the lowest common denominator?

—James

It’s easy to blame the Internet, but I think we see such behavior mostly because people generally gravitate toward trafficking in trivialities. Consider your own daily interactions. How much is witty repartee—and how much is the verbal equivalent of cat pictures? The Internet just makes it easier to see how boring our ordinary interactions are.

Understanding Ego Depletion

From your own experience, are you more likely to finish half a pizza by yourself on a) Friday night after a long work week or b) Sunday evening after a restful weekend? The answer that most people will give, of course, is “a.” And in case you hadn’t noticed, it’s on stressful days that many of us give in to temptation and choose unhealthy options. The connection between exhaustion and the consumption of junk food is not just a figment of your imagination.

And it is the reason why so many diets bite it in the midst of stressful situations, and why many resolutions derail in times of crisis.

How do we avoid breaking under stress? There are six simple rules.

1) Acknowledge the tension, don’t ignore it.

Usually in these situations, there’s an internal dialogue (albeit one of varying length) that goes something like this:

“I’m starving! I should go home and make a salad and finish off that leftover grilled chicken.”

“But it’s been such a long day. I don’t feel like cooking.” [Walks by popular spot for Chinese takeout] “Plus, beef lo mein sounds amazing right now.”

“Yes, yes it does, but you really need to finish those vegetables before they go bad, plus, they’ll be good with some dijon vinaigrette!”

“Not as good as those delicious noodles with all that tender beef.”

“Hello, remember the no carbs resolution? And the eat vegetables every day one, too? You’ve been doing so well!”

“Exactly, I’ve been so good! I can have this one treat…”

And so the battle is lost. This is the push-pull relationship between reason (eat well!) and impulse (eat that right now!). And here’s the reason we make bad decisions: we use our self-control every time we force ourselves to make the good, reasonable decision, and that self-control, like other human capacities, is limited.

2) Call it what it is: ego-depletion.

Eventually, when we’ve said “no” to enough yummy food, drinks, potential purchases, and forced ourselves to do enough unwanted chores, we find ourselves in a state that Roy Baumeister calls ego-depletion, where we don’t have any more energy to make good decisions. So–back to our earlier question–when you contemplate your Friday versus Sunday night selves, which one is more depleted? Obviously, the former.

You may call this condition by other names (stressed, exhausted, worn out, etc.) but depletion is the psychological sum of these feelings, of all the decisions you made that led to that moment. The decision to get up early instead of sleeping in, the decision to skip pastries every day on the way to work, the decision to stay at the office late to finish a project instead of leaving it for the next day (even though the boss was gone!), the decision not to skip the gym on the way home, and so on, and so forth. Because when you think about it, you’re not actually too tired to choose something healthy for dinner (after all, you can just as easily order soup and sautéed greens instead of beef lo mein and an order of fried gyoza), you’re simply out of will power to make that decision.

3) Understand ego-depletion.

Enter Baba Shiv (a professor at Stanford University) and Sasha Fedorikhin (a professor at Indiana University) who examined the idea that people yield to temptation more readily when the part of the brain responsible for deliberative thinking has its figurative hands full.

In this seminal experiment, a group of participants gathered in a room and were told that they would be given a number to remember, and which they were to repeat to another experimenter in a room down the hall. Easy enough, right? Well, the ease of the task actually depended on which of the two experimental groups you were in. You see, people in group 1 were given a two-digit number to remember. Let’s say, for the sake of illustration, that the number is 62. People in group two, however, were given a seven-digit number to remember, 3074581. Got that memorized? Okay!

Now here’s the twist: half way to the second room, a young lady was waiting by a table upon which sat a bowl of colorful fresh fruit and slices of fudgy chocolate cake. She asked each participant to choose which snack they would like after completing their task in the next room, and gave them a small ticket corresponding to their choice. As Baba and Sasha suspected, people laboring under the strain of remembering 3074581 chose chocolate cake far more often than those who had only 62 to recall. As it turned out, those managing greater cognitive strain were less able to overturn their instinctive desires.

(Photo: PetitPlat)

This simple experiment doesn’t really show how ego-depletion works, but it does demonstrate that even a simple cognitive load can alter decisions that could potentially have an effect on our lives and health. So consider how much greater the impact of days and days of difficult decisions and greater cognitive loads would be.

4) Include and consider the moral implications.

Depletion doesn’t only affect our ability to make good decisions, it also makes it harder for us to make honest ones. In one experiment that tested the relationship between depletion and honesty, my colleagues and I split participants into two groups, and had them complete something called a Stroop task, which is a simple task requiring only that the participant name aloud the color of the ink a word (which is itself a color) is written in. The task, however, has two forms: in the first, the color of the ink matches the word, called the “congruent” condition, in the second, the color of the ink differs from the word, called the “incongruent” condition. Go ahead and try both tasks yourself…

The congruent condition: color matches word.

The incongruent condition: color conflicts with word.

As you no doubt observed, naming the color in the incongruent version is far more difficult than in the congruent. Each time you repressed the word that popped instantly into your mind (the word itself) and forced yourself to name the color of the ink instead, you became slightly more depleted as a result of that repression.

As for the participants in our experiment, this was only the beginning. After they finished whichever task they were assigned to, we first offered them the opportunity to cheat. Participants were asked to take a short quiz on the history of Florida State University (where the experiment took place), for which they would be paid for the number of correct answers. They were asked to circle their answers on a sheet of paper, then transfer those answers to a bubble sheet. However, when participants sat down with the experimenter, they discovered she had run into a problem. “I’m sorry,” the experimenter would say with exasperation, “I’m almost out of bubble sheets! I only have one unmarked one left, and one that has the answers already marked.” She explained to participants that she did her best to erase the marks but that they’re still slightly visible. Annoyed with herself, she admits that she had hoped to give one more test today after that one, then asks a question: “Since you are the first of the last two participants of the day, you can choose which form you would like to use: the clean one or the premarked one.”

So what do you think participants did? Did they reason with themselves that they’d help the experimenter out and take the premarked sheet, and be fastidious about recording their accidents accurately? Or did they realize that this would tempt them to cheat, and leave the premarked sheet alone? Well, the answer largely depended on which Stroop task they had done: those who had struggled through the incongruent version chose the premarked sheet far more often than the unmarked. What this means is that depletion can cause us to put ourselves into compromising positions in the first place.

And what about the people, in either condition, who chose the premarked sheet? Once again, those who were depleted by the first task, once in a position to cheat, did so far more often than those who breezed through the congruent version of the task.

What this means is that when we become depleted, we’re not only more apt to make bad and/or dishonest choices, we’re also more likely to allow ourselves to be tempted to make them in the first place. Talk about double jeopardy.

5) Evade ego-depletion.

There’s a saying that nothing good happens after midnight, and arguably, depletion is behind this bit of folk wisdom. Unless you work the third shift, if you’re up after midnight it’s probably been a pretty long day for you, and at that point, you’re more likely to make sub-optimal decisions, as we’ve learned.

So how can we escape depletion?

A friend of mine named Dan Silverman once suggested an interesting approach during our time together at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, which is a delightful place for researchers to take a year off to think, plan, and eat very well. Every day, after a rich lunch, we were plied with nigh-irresistible desserts: cheesecake, chocolate tortes, profiteroles, beignets—you name it. It was difficult for all of us, but especially for poor Dan, who was forever at the mercy of his sweet tooth.

It was daily dilemma for my friend. Dan, who was an economist with high cholesterol, wanted dessert. But he also understood that eating dessert every day was not a good decision. He contemplated this problem (along with his other academic interests), and concluded that when faced with temptation, a wise person should occasionally succumb. After all, by doing so, said person can keep him- or herself from becoming overly depleted, which will provide strength for whatever unexpected temptations lie in wait. Dan decided that giving in to daily dessert would be his best defense against being caught unawares by temptation and weakness down the road.

In all seriousness though, we’ve all heard time and time again that if you restrict your diet too much, you’ll likely to go overboard and binge at some point. Well, it’s true. A crucial aspect of managing depletion and making good decisions is having ways to release stress and reset, and to plan for certain indulgences. In fact, I think one reason the Slow-Carb Diet seems to be so effective is because it advises dieters to take a day off (also called a “cheat” day–see item 4 above), which allows them to avoid becoming so deprived that they give up entirely. The key here is planning the indulgence rather than waiting until you have absolutely nothing left in the tank. It’s in the latter moments of desperation that you throw yourself on the couch with the whole pint of ice cream, not even making a pretense of portion control, and go to town while watching your favorite tv show.

Regardless of the indulgence, whether it’s a new pair of shoes, some “me time” where you turn off your phone, an ice cream sundae, or a night out—plan it ahead. While I don’t recommend daily dessert, this kind of release might help you face down challenges to your will power later.

6) Know Thyself.

(Image: AnEpicDay)

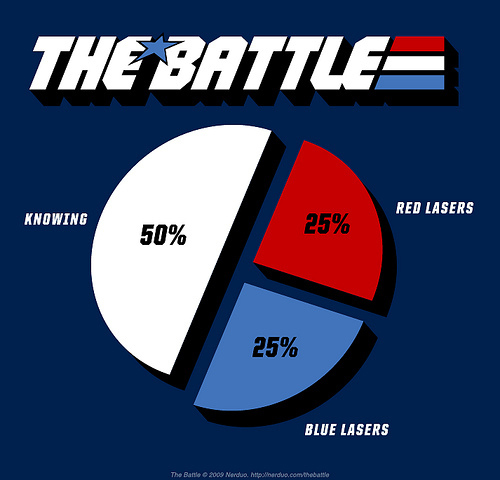

The reality of modern life is that we can’t always avoid depletion. But that doesn’t mean we’re helpless against it. Many people probably remember the G.I. Joe cartoon catch phrase: “Knowing is half the battle.” While this served in the context of PSAs of various stripes, it can help us here as well. Simply knowing you can become depleted, and moreover, knowing the kinds of decisions you might make as a result, makes you far better equipped to handle difficult situations when and as they arise.

This blog originally appeared on Tim Ferriss’ blog, here.

Please Don’t Steal the Charmin

A Chinese tourist destination decided to experiment with offering free toilet paper, the Wall Street Journal reports. Rather than the usual procedure in China, where people bring their own toilet paper, in Qingdao they now encounter a toilet paper dispenser when they enter the public restroom (and, naturally, pass it again on the way out).

Now that the dispensers have been in the bathrooms for a month, it has become clear that visitors to Qingdao’s restrooms take an astonishing amount of care for their personal hygiene. Two kilometers (1.24 miles) of toilet paper disappear each day.

In this case, the excess T.P. use seems to reflect our findings with other forms of cheating and stealing: most people are cheating a little, rather than a few people cheating a lot. Of course, there are exceptions.

The toilet paper scenario meets the right conditions for people to cheat: they’ve got the opportunity and face no consequences for taking a bit extra, they can use the toilet paper later, and they can rationalize their behavior. They might tell themselves that the government is paying for their bathroom use in general, not only for that specific restroom; or that it’s expected that they’d take extra on the way out; or that they’ve already paid for it in the form of taxes; or that the government deserves what it gets. They’ve easily justified a way to walk out with wads of toilet paper and an untroubled conscience.

But why steal something like toilet paper?

One explanation probably has to do with the power of free. Maybe Qingdao’s bathroom users are so enchanted with the idea of FREE toilet paper that they would take it in any case, regardless of what they know about its value or usefulness.

Another explanation that pops up a lot with government-provided goods is the tragedy of the commons. The theory goes that individuals will use a limited resource (like commons for grazing animals) in an unsustainable way, so long as they get the full benefit and the harm is spread across the group. In the case of the toilet paper, the theory suggests that people use no more than they need when they have to pay for it individually. But when the cost is spread out across Qingdao, they are happy to overuse the resource. The usual prescription is to make individuals pay for the resource on their own—in other words, to go back to the days without free toilet paper.

But there might be a better solution. We can take research from behavioral economics to think of ideas that may be less strict than taking away the free toilet paper and, instead, simply push people toward lighter use of the product. How about replacing the landscape paintings above some dispensers with a picture of watching eyes—a tactic that has effectively encouraged people to clean up after themselves and pay on the honor system.

In Qingdao, restroom managers have attempted to confront their problem by posting a poetic reminder of social responsibility:

Convenience for you,

convenience for me,

civility is there for all to see.

My paper use, your paper use,

conservation is up to us.

The sign hasn’t had a noticable effect yet, but it may be on the right track. Reminders like the poem sometimes work (p.41, The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty) to keep people from stealing toilet paper. The Qingdao bathroom poets appeal to bathroom users’ social norms (“civility is there for all to see”) and allude to future benefits (convenience and conservation)—tactics that have been shown to work in getting people to wash their hands. But getting some sort of assent—like a signature—may be even more effective.

For example, bathroom visitors could sign in under a poem like this:

Future benefits and social obligations

Should outweigh your current temptations

You agree not to steal by signing below

You’ll take just what you need when you need to goSign here: _______________________

_______________________

_______________________

Of course, if the bathroom management is going to ask people to sign anywhere, they might also want to keep watch over the “free” pens.

~Susan Wunderink~

Swiss Army People

Plato once said that people are like dirt. They can nourish you or stunt your growth. This seems sage and reasonable, but I think people are more like Swiss Army knives (To be fair, Plato did not have the benefit of knowing of such a tool, so I don’t think I’m detracting from his comparison in the least). Swiss Army knives, as we all know, are incredibly versatile, and have a tool for almost any situation. Need to open a package—it’s got a knife! Sharing beers with friends on the beach—it’s got an opener! Have something in your teeth—there’s a toothpick for that! Need to do a little electrical work—it’s a got a tool that can strip wires! The downside is that Swiss Army knives are not particularly good for any specific purpose because any really intricate task is going to require much more specific tools.

People are a lot like Swiss Army knives from this perspective, and I am saying this with tremendous appreciation. A lot of the research in behavioral economists criticizes people for various ineptitudes: why we don’t save money, why we don’t exercise, why we text and drive. And it’s true, there’s a lot to criticize and a lot that goes wrong in our decision-making processes, but when you consider just how versatile we are, it’s very impressive. Essentially, we do a lot of things sort of OK. We can reason moderately well about money, we’re often pretty good with various relationships, we’re fairly moral, and most of the time we don’t kill ourselves or others. Not bad if you think about it this way!

Now, some people are more like the specialty tools, like post hole diggers, or lemon zesters, or cigar cutters; in these cases these individuals are truly excellent in certain domains. But often these people aren’t the best at navigating the world in a pragmatic fashion. There are often savants, like Kim Peek (the person that Rain Man is based on), who certainly can’t handle the day-to-day on their own, but have extraordinary abilities in other spheres. And plenty of geniuses have similar problems; take Bobby Fischer’s statelessness and detentions, or van Gogh’s famously self-detrimental tendencies and ultimate suicide. If everyone were like these folks, our species would surely be in peril. If people were all specialized, and could only think numerically, or long-term, or probabilistically, what would life be like? Neither rich nor long.

Of course these people provide inspiration and spur progress, and we admire and celebrate many of them (who don’t put their genius to antisocial use), but we should be grateful that most of us are more like Swiss Army knives.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like