Ask Ariely: On Seeing Solutions, Emotional Actions, and Fun Foods

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My girlfriend hates wearing contacts and has been talking about getting laser eye surgery ever since I’ve known her. But she’s never taken the first step of getting an evaluation. I had the surgery a few years ago, and it was like magic: One day I couldn’t see—and the next day I could. It took me about two years to get my act together, do the research and take off time for the procedure. How can I help my girlfriend to shorten this timeline?

—Phil

I’d suggest various forms of encouragement. For an incentive, offer to pay half the bill. To add a deadline, say that your offer to pay only holds if she has the procedure within the next two months. And to add social pressure to the mix, ask some of her friends to chip in for the effort but ask them to condition their gifts on the same two-month timeline. That should do it.

Of course, if you do this, you should expect that at some point she will set up some incentives for things that she wants you to do. Try to accept these cheerfully in the spirit of making your relationship more exciting and productive.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Last week, two different stories about senseless murders were all over the news. The first was about Cecil, Zimbabwe’s most famous lion, who was hunted down and killed as a trophy by a dentist from Minnesota. The second was about Samuel DuBose, an unarmed black motorist shot dead by a police officer in a routine traffic stop. Guess which story received more attention and outrage? Do we really care more about lions than people?

—Janet

Your question hinges on what we mean when we use the term caring. When you look at the volume of public outrage and the amount of ink spilled, it can sometimes seem that the loss of an endangered animal matters more. Sadly, that’s because, at least for some of us, the news of an animal’s death can have more emotional impact than the news of a person’s death.

Of course, this isn’t true for those who were close to the deceased, have personally experienced similar tragedies or have worked to fight similar injustices. But for those who experience such tragedies only via the news, the human loss sometimes doesn’t pull as much at their emotional strings.

This tendency has limits, though. If you gave most people two buttons, told them that pressing one would kill an endangered animal and pressing the other would kill a random fellow citizen, and ordered them to push one, very few would press the kill-a-person button. In this sort of direct comparison, I’d predict, almost everyone would prefer to kill the animal. Comparing lives more directly engages our cognition, not our emotions—and so the type of caring that emerges reflects our higher empathy for human beings and their families.

In other words, when we really think about it, we care more about humans—but we are often called to act based on our emotions, where our caring works quite differently.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

How can I get my kids to eat more vegetables?

—Yael

How about trying a new version of Popeye the Sailor, who used to gulp down spinach at moments of crisis and instantly grow stronger? You could modernize the Popeye approach by changing the language at the dinner table and talking about passing the Iron Man (kale), the Green Lantern (peas), the Superman (tomatoes), the Penguin (Oreos) and the Joker (soda). (My pairing of characters and foods may reflect some of my parental biases.)

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

A Modified Introduction to “Irrationally Yours:”

In 1984, as a 17-year-old high-school student in Israel, I was a member of a youth movement that focused on study, civic work and preparation for military service. Our graduation ceremonies often featured big fires, intended to dramatize our patriotic fervor. That year, some of our leaders had brought back military supplies to help make the blaze especially intense.

One Friday afternoon, as we began putting away these materials, there was an accident. Nobody knows exactly what happened, but a spark must have been struck somewhere. A large magnesium flare—the kind that the Israeli military uses to light up a battlefield—exploded right next to me. In a moment, I was engulfed by flames.

The fire nearly killed me. About 70% of my body was covered in third-degree burns. In a matter of seconds, my life had changed irreversibly. Looking back now, more than three decades later, I realize that my awful new situation had one unexpected and positive effect: It began my career as a serious observer of the peculiarities of human behavior.

The explosion marked the start of a three-year period of hospitalization and surgeries—first in the emergency department of Beilinson Hospital, then in Tel Hashomer Hospital, both near Tel Aviv. I’ll never forget the day, perhaps four months after my injury, when I first saw myself in a full-length mirror. Before the accident, I had been a decent-looking teenager. But that day, I saw something completely different. My eyes were pulled severely to the side. The right side of my mouth and my nose were both charred and distorted. So was my right ear.

Was this really me? It was hard to see, believe or accept. Why was I still here? What would my future be, looking like this?

The burns and their treatment caused me extreme pain over a long period—a kind of pain that is more intense and lasting than almost any other medical condition. But since I had little else to do and badly needed distraction, I began to notice and record things.

For example, every day, I had to have a soaking bath that involved removing my bandages and scraping off my dead skin and flesh. The nurses would rip off the dressings all at once, without a break. It was excruciating, but the nurses insisted that tearing the bandages off was the best way.

One day, one of the nurses allowed me a bit of control over the process, and I found the treatment somewhat more tolerable. This made me wonder if having more control over the process would be better in general, but given my helpless position, I had little influence over the way I was treated.

After years of treatment, I left the hospital and went to Tel Aviv University. I decided to study psychology. My harrowing years had left me deeply interested in understanding how we experience pain and in the experimental method.

So I carried out laboratory experiments on myself, my friends and volunteers, using moderate (and safe) physical pain induced by heat, cold water, pressure and loud sounds—even the psychological pain of losing money in the stock market—to probe for answers. I learned that there are better and worse ways to deliver pain—and that my nurses’ methods hadn’t been the best ones. (One should remove the bandages slowly, not rip them off, and one should start from the most painful parts, then move toward the least.) If my nurses, despite all their experience with burn victims, had erred in treating the patients they cared so much about, other professionals might also be misunderstanding the consequences of their behaviors and make poor decisions.

Soon, I found, my personal and professional lives had become intertwined. For years, I felt the burden of my scars: the unending pain, the odd-looking medical braces, the pressure bandages that covered me from head to toe, the feeling of having gone through some kind of weird door and of living separately from the day-to-day experiences of my previous self and other “normal” people. I’d become an observer of my own life, as if I were watching an experiment on someone else—and I looked anew at other people as well.

This new approach became central to my work. Remembering the placebos given instead of medications during some treatments, I conducted experiments to explore the effects of expectations on painful treatments. (They can dramatically change our experiences—and even the intensity of the pain we feel.) Remembering how it felt to be given difficult information in the hospital, I tried to figure out how best to break bad news to patients. (Slowly, and in steps.) I kept finding topics that crossed the personal/professional boundary, and over time, I learned more about my own decisions and the behavior of those around me.

I saw people who managed their suffering and triumphed, and I saw others who caved in to fear and terror. I tried to take apart mundane daily activities—about why we shop, drive, volunteer, interact with co-workers, take risks, fight and behave thoughtlessly. And I couldn’t help noticing the intricate fibers that entwine our romantic life. (Fortunately, I never lost my sense of humor.)

All these questions began to weave their way into my research. I grew increasingly adept at observing how people went about their daily lives, prone to wonder about human habits, eager to explore the reasons for our behavior and motivated to find ways to make us behave slightly better.

My accident happened more than 30 years ago, and if any good came out of it, maybe it is this: I like to believe that the disaster and its aftereffects made me better able to understand myself and others. Maybe I’m rationalizing. We human beings do that exceptionally well: By trying to see something awful in a more positive light, we’re able to make sense of it, or at least make it more tolerable.

After years of writing scholarly papers on these topics, I started writing about my research and its implications in a more conversational, less academic way. And perhaps because I described how my research grew out of my own struggles, many people started sharing their personal challenges with me. With experience (warning: second rationalization coming), I got better at answering their questions. And I would like to believe that my advice was even helpful sometimes.

Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think that my injury was worth it. I have spent every day of my adult years in varying degrees of pain. I have endured, over and over, the dysfunction of the medical system. I have been exposed to an astonishing number of medical procedures and odd human interactions. I am more comfortable in public these days, but my scars still make me feel out of place in most social circumstances.

But—whether I’m rationalizing or not—I did learn important lessons from my injury, my time in the hospital, the years that followed, the research that emerged from my ordeal, and the questions and challenges that people have shared with me over the years. These have become my microscope on life.

My latest book, Irrationally Yours, which is based on my Wall Street Journal column “Ask Ariely,” was recently published by HarperCollins. See this article on the WSJ here.

Ask Ariely: On Minding the Gap, Making Contact, and Meaningful Kisses

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I do lots of research online for work. I’ve noticed that, as more and more information sources become available, I’m less and less sure about my research’s quality. Is my trust in online information dwindling?

—Maribel

I suspect that the real reason isn’t trust. During my first years at university, I took many introductory classes and felt that I knew a lot about all the topics I was studying, from physiology to metaphysics. But once I got to graduate school and started reading more academic papers, I realized how large the gap was between what I knew and what I needed to learn. (Over the years, this gap has only widened.)

I suspect that your online searches have a similar effect on you. They show you the size of the gulf between what you know from online research and the other knowable information still out there.

The magnitude of this gap can be depressing, maybe even paralyzing. But the good news is that a more realistic view of how little we really know—and more humility—can open the door to more data and fewer opinions.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am a saleswoman working at a major company. Recently, we’ve been told to try to make physical contact with customers—for example, by touching their arm when stressing an important point. I don’t like this approach. Do you know if it has any scientific basis?

—Ayala

You might not want to hear the answer, but we do have some evidence suggesting the efficacy of physical touch. Perhaps someone at your company read about a study by Jonathan Levav of Columbia University and Jennifer Argo of the University of Alberta published in Psychological Science in 2010. They found that individuals who experienced physical contact from women—a handshake or a touch on the shoulder—felt calmer and safer, and consequently made riskier financial decisions.

Another study published two years later—by Paul Zak and his team, in Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine—found that after receiving a 15-minute massage (especially the females) were more willing to give their money to others. Dr. Paul also found that their blood contained elevated levels of oxytocin, a hormone linked to trust and intimacy.

More research backs these findings up. One 2010 study, carried out by researchers at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, found that 45 minutes of Swedish massage reduced the levels of hormones that are released during stress and tied to aggressive behavior.

And why stop there? Armed with this information, you could go to your boss and suggest that massaging the customers is inefficient: There are lots of them, and they stay in the store for only a short time. Why not massage the employees each morning instead to make them more friendly and trusting?

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why does a first kiss feel so magical? Is it because of the law of decreasing marginal utility, according to which the utility derived from every ensuing kiss decreases, or is it because (besides the fun of the clinch itself) the kiss provides you with so much new information—notably, that the other person feels the same way about you, which in most cases offers a huge relief from the anxiety that you were on a one-way road?

—Gaurav

I suspect that the reason first kisses are special isn’t related to waning marginal utility or rising familiarity—and certainly not because they’re better. (The technique, strategy, approach and objective performance of a smooch probably increases over time.) The key is that a first kiss has tremendous meaning attached to it. It provides a transition to a new kind of relationship and a new way for two people to think about themselves, separately and together. Maybe it is time to try to imbue our other kisses with more meaning?

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Funny Decisions, Security Insecurity, and Anthrax Horn

To celebrate today’s Ask Ariely column, I’d like to share the final Reader Response video. (But don’t worry, you can always check out the rest of the collection in this album.)

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Is there any research on the relationship between humor and the quality of decision-making? Does humor make for better or worse decisions?

—Meher

Both. On the positive side, it has been shown that humor can improve creativity, which broadens the perspective from which we examine a problem and helps us to come up with novel solutions. In one study, researchers gave subjects a box of tacks, a set of matches and a candle. Their assigned task was to affix the candle to the wall so that it wouldn’t drip on the carpet when lighted. Subjects who had watched an amusing video clip before the task were more likely to recognize the solution: tack the box (which held the tacks) to the wall and use it as the candle’s base.

On the negative side, humor gets us to believe that things are safe, which can lead to risk-taking behavior. For example, recent research in the lab of Peter McGraw at the University of Colorado, Boulder, shows that humorous public service announcements are less effective than their traditional, nonhumorous scary counterparts. Why? Because the joking tone puts people at ease.

So as far we can tell, the effect of humor on the quality of decision-making is mixed. But using humor in an interpersonal relationship is certainly a good thing. It enhances liking and trust—and Prof. McGraw’s findings also suggest that humorous people are more attractive as lovers.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My wife and I bought a new house and are fighting about the door locks. She wants to replace all of the locks, fearing that some people might have keys that would let them enter. I think that there are many ways a thief could break into the house without bothering with a single door, so why spend money to deal with that negligible part of the problem? It seems to me that her irrational insecurity blinds her from the truth. Any advice?

—Darin

Your wife’s fear has to do with the ease and vividness of imagining a bad outcome rather than the probability of something actually happening. After the attacks of 9/11, for example, we were all more afraid of flying, so some people switched to driving. As a consequence, over the following months, more people died from car accidents. The increase in the number of people dying from car accidents was much higher than the number of people dying on flights.

This aspect of emotions is also why we are more afraid of Ebola (which, thankfully, did not kill many people in the U.S.) than of the seasonal flu (which kills thousands of people every year). Given that the power of emotions is connected to their vividness, it is only partially useful to try to counteract them by providing accurate information about probability. Sometimes it is better just to try to deal with our emotions more directly.

Your wife’s fear may not be rational, but neither is your refusal to take such a small action to make her less worried. Why not use this as an opportunity to look at all the new locking technologies out there (some of them are really interesting). You could turn replacing the locks into a fun activity for yourself.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Is there a way to use behavioral economics to stop rhino poaching? Some people believe that consuming rhino horn cures a range of ailments, and though this is entirely mythological, it is hard to get them to change their minds about its supposed health benefits. Can you think of a way to undermine this market?

—Veronica

Sadly, it is very difficult to use information or experience to counteract such mythical beliefs. The only way to fight them is with other beliefs. One approach would be take advantage of the widespread myth about the link between rhino horn and anthrax, and work hard to propagate this false belief. People might still believe in the healing power of rhino horn, but their fear of anthrax might overpower it.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Reader Response: Day 13

Review of Irrationally yours (ASSOCIATED PRESS)

`IRRATIONALLY YOURS’ DELIVERS CLEVER ADVICE WRAPPED IN HUMOR

BY CHRISTINA LEDBETTER

ASSOCIATED PRESS

In his compilation of articles from his Wall Street Journal column, “Ask Ariely,” Dan Ariely wraps in a clever bow all the questions we’ve ever wanted answered concerning the behavioral intricacies that dictate the decisions we make.

He offers extremely practical advice, like babysitting friends’ children for an entire week to better estimate the costs and benefits of having children, in addition to brain-stretching teasers like how to choose the least used bathroom stall (it’s the one furthest from the door).

As always, Ariely’s intelligence is swathed in humility and charm. Bolstering his already likable writing style are cartoons by the talented William Haefeli, which help to humorously drive home Ariely’s points.

While “Irrationally Yours” offers some tangible steps on how one can stick to a diet or have a better time vacationing, it also offers something more. For example, in one piece we learn exactly why long commutes are so hard on us (in a word, unpredictability). In another, we learn how to feel better about ourselves in the midst of that traffic (in another word, altruism). On one page he offers concrete solutions, and on another, a different way to think about the problem in the first place, therefore minimizing our dissatisfaction.

Some answers are very insightful, with an added dose of humor. A few land solidly on the witty side and offer little sound advice. However, it’s this mix of academics and laughs that makes the book not only useful, but also enjoyable. Without the drawings and one-off jokey answers, “Irrationally Yours” could prove an information overload for someone seeking real decision-making help. But combine Ariely’s obvious intellect with funny quips and whip-smart cartoons, and you have a read that could lightheartedly change your life.

So for those less interested in a detailed write-up of lengthy experiments conducted using the scientific method and more interested in the conclusions those experiments deliver, Ariely’s words will offer high quality rationality with a quick pace. There is even a section providing insight about the best way to recommend a book. Taking a cue from Ariely himself, let’s just say heightened expectations are a safe bet this time.

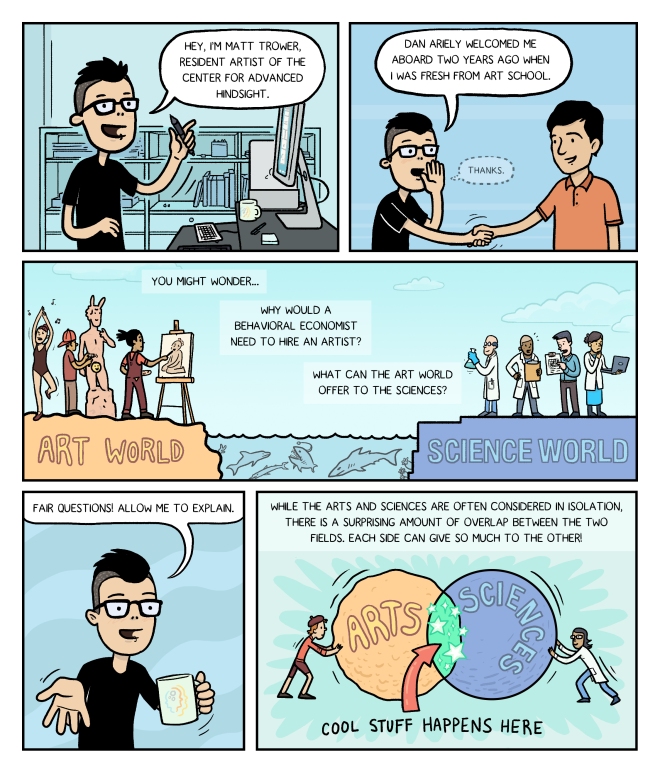

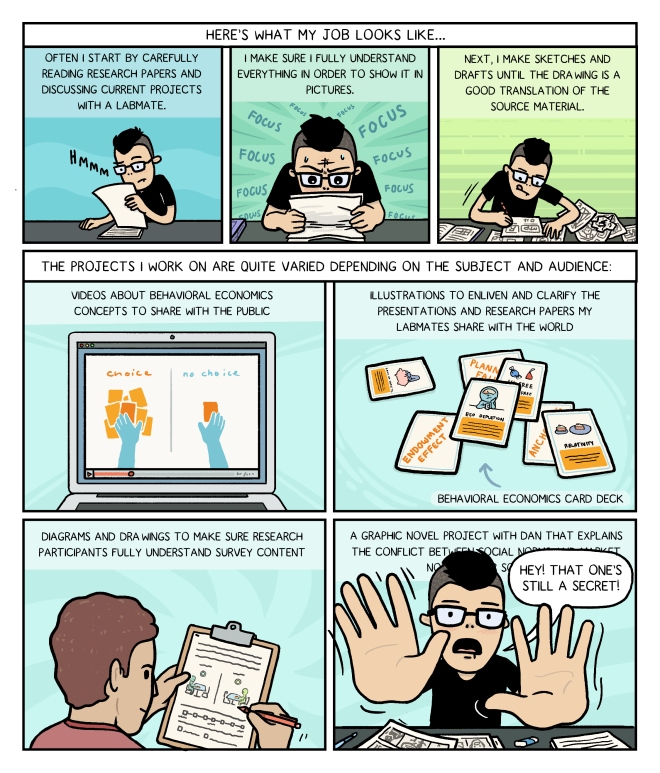

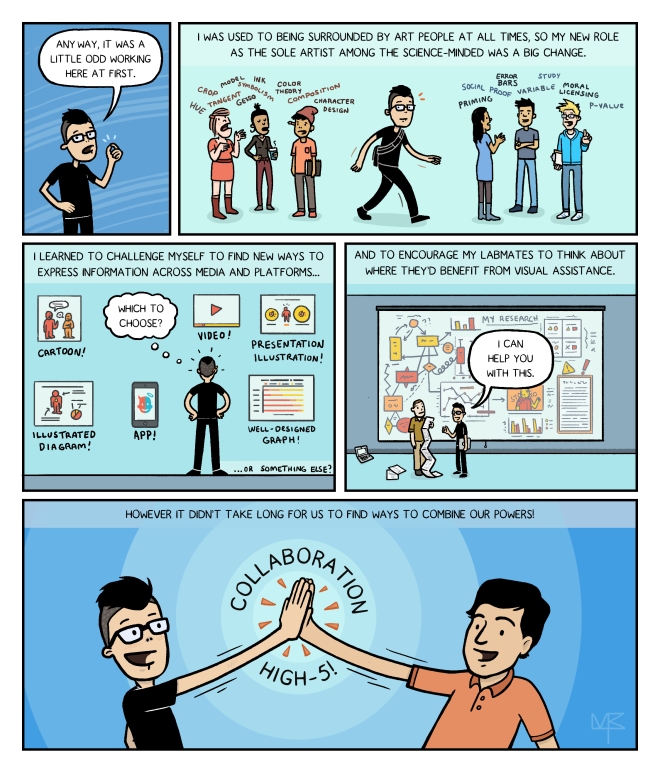

Why do we have an artist in the lab?

Ask Ariely: On Lasting Gifts, Pre-engagement, and Incentivizing Scientists

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What is the best gift to give my mom for Mother’s Day?

—Logan

Mother’s Day comes once a year, but mothering is an everyday activity—which is why you should try to get your mother a gift that keeps giving in some way for the entire year. In general, transient things don’t make great gifts: flowers, gift certificates, cleaning supplies. Here are some better ideas: A special pillowcase, a nice case for her smartphone, a good wallet, an artistic keychain—or anything else that she’s likely to use daily, which will remind her of your gratitude. And of course, say something especially nice when you give it to her: The giving-ceremony and the accompanying words will define the way she will think about the gift and her relationship with you. And remember—you can’t be too mushy.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My partner and I have been together for a few years. At some point, I am sure we will get married. However, I’m not in any hurry to get engaged, let alone worry about a wedding date and all the planning that comes after. My partner, on the other hand, he is perfectly ready. What should I do?

—Aline

First, let’s ask why your boyfriend is so keen to get engaged soon. Perhaps it’s because you’ve been dating for a long time, and he wants to feel that the relationship is moving forward. Or perhaps he isn’t sure that the two of you really are going to get married, and he wants to try to seal the deal.

Depending on his reasons, you might be able to help assuage the root cause of his concern without getting engaged. If his concern is just about moving forward, you can take some lessons from game designers. Right now, you are playing a three-step “game”—dating, engagement, marriage. You don’t want to move to level two or three yet, so maybe you can design a game with more levels—with several steps between dating and marriage. There’s dating, dating steadily, dating seriously, pre-engagement, engagement and post-engagement. By thinking in terms of these additional steps, your boyfriend could get a feeling of progress while you avoid a feeling of pressure.

On the other hand, if he’s looking for more certainty about where you two are headed, you can do all kinds of things to make clear that you intend to stay with him for a very long time. Maybe you could set up a joint bank account, make plans for things far in the future or buy a car together.

If you don’t know the real concern, use both approaches.

One last personal note: In my experience, whenever we face a decision about something good—and presumably, getting married is something good—delaying is rarely better. The one downside, of course, is that once you do decide to get married, your parents are going to start calling to ask when you are going to give them grandchildren.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

How can I find scientists who will study people’s poop-pickup behaviors and help design campaigns to get more people to clean up after their dogs?

—Emily

Offer them treats. Treats for scientists are a bit more complex than treats for pets, but if you were to announce a competition of ideas to solve the dog-poop problem, promise to try the different proposals in a scientific way and announce the winner publicly, that combination of ego and data would probably work nicely.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Reasonable Requests, Trash Talk, and Paper Piles

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I fly by myself every week for work. I always fly coach and try to book my trips months in advance so I can get an aisle seat closer to the front of the plane. With fuller flights nowadays, I am frequently asked to move to accommodate a family or a couple who want to sit next to each other. I usually say yes and end up in a middle seat at the rear of the plane, which I hate. On the few occasions I have declined to move, the cabin crew has treated me like the enemy for the entire flight. How do I handle such situations?

—Kevin

Many years ago, Harvard psychology professor Ellen Langer carried out one of my all-time favorite studies. She asked her research assistants to look for lines for photocopiers, approach someone waiting to make copies and say, “Excuse me, can I get in line in front of you?” Unsurprisingly, this request was usually refused. Prof. Langer then had her research assistants change their phrasing and instead ask, “Excuse me, can I get in line in front of you—I need to make a photocopy” With this new version, they were frequently allowed to cut in. Obviously, the second phrase held no new information—why would anyone join this line if not to make a photocopy? But the longer phrasing had the structure of a reason-based-request: Excuse me, may I do X, I need Y. Prof. Langer showed that because people often don’t pay attention to what we say, it is sometimes enough to say something that sounds reasonable—and people will often agree.

So what can you say to the flight crew? It doesn’t really matter; it just needs to sound like a reason.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

The other day, I saw someone throw out garbage from her car. Other than pick up after her, should I have said something? If so, what? I was concerned about starting a confrontation that could have turned ugly.

—Blaine

You should have certainly said something—perhaps something like, “Excuse me—I’m new in town, and I’m trying to figure out the local customs. Is throwing out trash from the car window something that is common here?”

You should have spoken up not only because it might make her think twice in the future but also for you. At some point, you will inevitably encounter bigger injustices and even more inappropriate behavior. How can you expect to stand firm in these large cases if something as simple as a comment about trash left you too fearful to speak up? Think about such small cases of confrontation as training wheels that will help move you toward becoming the person you want to be—and start practicing.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have this pile of papers on my desk. It is growing by the day, and the clutter is driving me crazy. At the same time, I don’t feel like I can handle my regular workload, so I keep postponing clearing up the pile—and it keeps getting larger and more daunting. Any advice?

—Marc

Sometimes, we need to be forced to make a decision. My advice: spill a cup of coffee on your pile of papers. A few weeks ago, I was grappling with a similar problem, and one morning, while on a video conference call, I reached out to pick up my coffee and knocked it onto the pile of papers. I then had to look at each page and decide whether it was worth cleaning and drying. Most of them were useless.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

The Oscars' "Meta-Film" Bias

For the third time in four years, the Oscar for Best Picture has gone to a film about film – a “meta-film” if you will. In 2011, The Artist examined film and art from behind the scenes and last year, Birdman did the same with a darker edge.

For the third time in four years, the Oscar for Best Picture has gone to a film about film – a “meta-film” if you will. In 2011, The Artist examined film and art from behind the scenes and last year, Birdman did the same with a darker edge.

The 2012 best picture went to Argo prompting Stephen Colbert to incisively comment, “Big surprise, Hollywood honors the film where Hollywood is the hero.” Notably, the only recent year without a meta-film winner, 2013, was also the only year without a meta-film in the Best Picture category.

If we wanted to, we could take this observation and ask the question: What does this say about the Academy? Then we could use this question as an excuse to gleefully criticize the Oscars for the duration of a news cycle.

But instead, why don’t we take this Academy bias and ask a harder question: Are we not all as biased as the Oscars?

The Oscars have always been a huge self-congratulating event. The event allows artistic elites to indirectly praise themselves by praising others and the magic of art. What’s important to remember, however, is that this self-congratulatory behavior is not confined to the Oscars; it is a fundamental human tendency.

Hollywood’s bias to praise films that embody Hollywood values and issues is just another example of how people in general excessively praise politicians, professionals, and pastors who uphold their own personal values.

The Oscars, punk rock concerts, and Sunday-morning church services all often reiterate this wonderful self-congratulation. “Movies are magic.” “Punks are awesome and the Man is terrible.” “We are the people of God and we alone follow the truth.” These experiences make us feel good because they affirm the core of our identity and the rightness of our groups, in a socially acceptable way.

Psychological research shows that people derive their self-worth from their groups and beliefs. Accordingly, people are motivated to uplift their own groups and beliefs while derogating outsiders and rival beliefs. This can provide immediate joy, but here’s where the warning comes in.

The desire to see our own beliefs and groups as wonderful may weaken our ability to perceive the actual truth. Furthermore, it may weaken our ability to understand how others who do not hold our biases will perceive the world.

The Oscars picking The Artist (in my opinion a delightful film), Argo (in my opinion a great film), and Birdman (in my opinion a stylish thoughtful film) is no immediate cause for alarm. However, these Oscar selections offer insight into a fundamental tendency of human nature, and that tendency is causes for constant alarm. It is the tendency that leads to social bias and societal problems.

In a culture where winners are often selected by like-minded individuals, we must watch out for this tendency in ourselves, others, and society at large. We all, the Academy very much included, should try and genuinely celebrate people other than themselves.

By Troy Campbell

@TroyHCampbell studies marketing as it relates to identity, beliefs, and enjoyment here at the Center for Advanced Hindsight and the Duke University Fuqua School of Business. In Fall 2015 he will begin as an assistant professor at the University of Oregon Lundquist College of Business.

@TroyHCampbell studies marketing as it relates to identity, beliefs, and enjoyment here at the Center for Advanced Hindsight and the Duke University Fuqua School of Business. In Fall 2015 he will begin as an assistant professor at the University of Oregon Lundquist College of Business.

You may also enjoy his other posts mixing psychology and movies:

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like