Email Notifications

How many of our emails should we know about the moment someone decides to email us?

205 billion. That’s the number of emails we sent and received in 2015, and that number is expected to grow to 246 billion by 2019.[1] What does this mean for most of us? A steady stream of new messages coming into our inboxes throughout the day. And for most of us, it seems to be a norm to keep our inboxes open throughout the work day. We focus on the tasks we have at hand, and each “ping” from our inbox draws our attention, even if briefly, before we return back to our work.

The problem here is the high cost of interruption. This cost includes three categories: 1) time cost 2) performance cost 3) stress/ emotional well-being.

Time Cost In terms of time cost, researches have shown that any switching between tasks results in a loss of time. In other words, “multi-tasking” is a misnomer – we aren’t actually doing two tasks at once. We are doing one task, switching to the other, and then switching to the original task. One study showed that after switching tasks, it took an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds for people to get back to their original task.[2]

Performance Cost It should be no surprise to us that distraction can cause reductions in cognitive performance. In psychological terms, “task-irrelevant thoughts,” that is – thoughts that are unrelated to the task at hand, have indeed been shown to have deleterious effects on performance.[3]

A recent study published in The Journal of Experimental Psychology illustrates how this plays out for cell phones in particular, focusing on the distraction that cell phone notifications can create. In this study, participants were tasked with completing a task involving seeing items and pressing a button every time the item was a digit from 1-9, unless it was the number 3. Some were interrupted with notifications and others were not. The study found that the notification groups were more likely to make errors than the no-interruption group.

Stress/Emotional Well-Being A third factor to consider with interruptions is the effect they have on people’s well being. Task switching is fatiguing for us; it depletes us. One study showed that interruptions resulted in higher feelings of stress, pressure and effort.[4]

At this point, it should be painfully clear to us that we need to be worried about the interruptions-economy. What value interruptions provide, under what conditions, and what are their costs? A little ping may seem innocuous, but there is cumulating evidence that the cost of an interruption is higher than we realize, and of course given the sheer number of interruptions, their combined effect can very quickly become substantial.

If email interruptions can have all these negative effects, what can we do to reduce them? The first thing we should question is this idea that all emails are created equal. Should each email be able to interrupt people? Is the email from someone’s boss as important as the weekly industry newsletter he’s signed up for? What if we designed a different system in which emails were not treated equally?

In a previous study, we looked at how many emails truly are worthy of interruption. We asked people to look at the last 40 emails they received and asked them how soon they really needed to have seen each email. Immediately? At some point today? At some point this week? At some point this month? No need to see it at all?

As it turns out, very few – only 12%! – of emails need to be seen within 5 minutes of being sent.

7% of emails need to be seen within 1 hour, 4% within 4 hours, 17% by the end of the day, 10% by the end of the week, 15% at some point, and a whopping 34% fell into the “no need to see it” category.

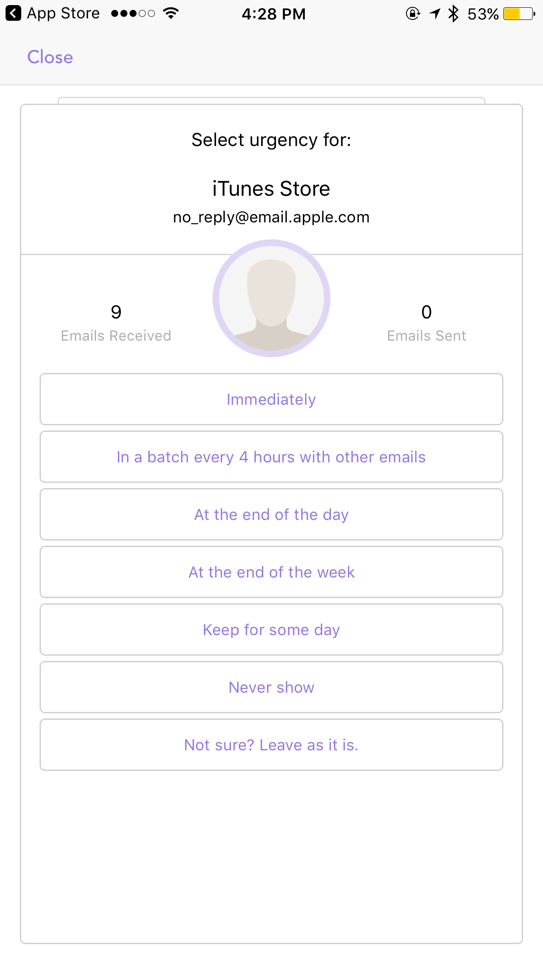

With that initial starting point – the idea that very few emails need to be seen right away – we set out to build a tool to allow people create rules for receiving emails. We used a very simple sorting technique: sorting emails based on the sender. In other words, depending on the sender, emails could be set to be received at different intervals. No complex AI or learning mechanisms.

Example of instructions users were given

Example of prompt to set rule by each sender

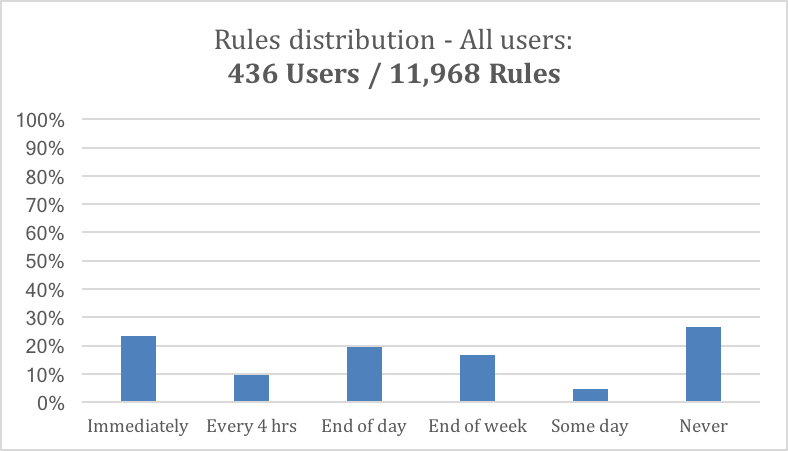

What did we find? People proceeded to create rules based on senders. Similar to our initial findings, only 23% of emails were set up to be in the “immediate” category. 10% were relegated to the every-4-hours category, 19% to the end of the day, 16% to the end of the week, 5% to some day and a whopping 27% to the “never” category.

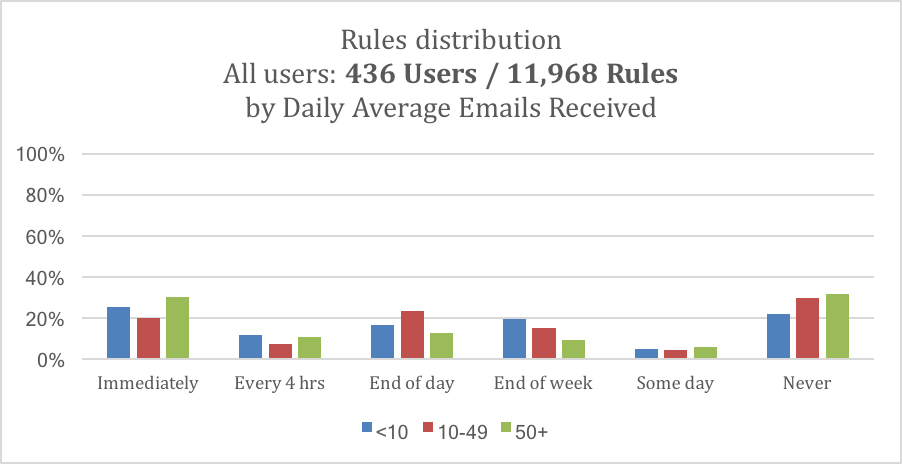

We also looked at whether people who received high vs, low quantities of emails behaved differently. While on the whole they had similar behavior, one interesting point of note is that people with 50+ emails/day put highest number of emails into “immediately bucket” (30%) vs. 10-49 emails/day (20%) and <10 emails/day (26%).

Overall, the key point and opportunity we should take away from all of this is that a very simple mechanism can have an impact, creating a significant amount of benefit for people. If you’d like to try this app for improving your email process for yourself, you can download it here.

[1] http://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Email-Statistics-Report-2015-2019-Executive-Summary.pdf

[2] Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Paper presented at the 107-110. doi:10.1145/1357054.1357072

[3] Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2006). The restless mind. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 946–958. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.946

[4] Mark, G., Gudith, D., & Klocke, U. (2008). The cost of interrupted work: More speed and stress. Paper presented at the 107-110. doi:10.1145/1357054.1357072

In the Home of the Free, Why Are So Many People in Prison?

The high rate of incarceration in the United States is fraught with social and economic costs. Relatively recent increases in our incarceration rate make us an international outlier and carry a price tag of more than $80 billion annually (more than quadruple the 1980 corrections expenditures). This is despite an overall reduction in crime rates between 1990 and 2012.

In addition to the overall incarceration rate, there is a staggering gap between the incarceration rates of black Americans and white Americans. The gap is most clearly seen between black and white males. Based on 2001 incarceration rates, nearly 1 in 3 (32.2%) black males will will be sentenced to prison during their lifetimes, whereas the rate for white males is 5.9%.

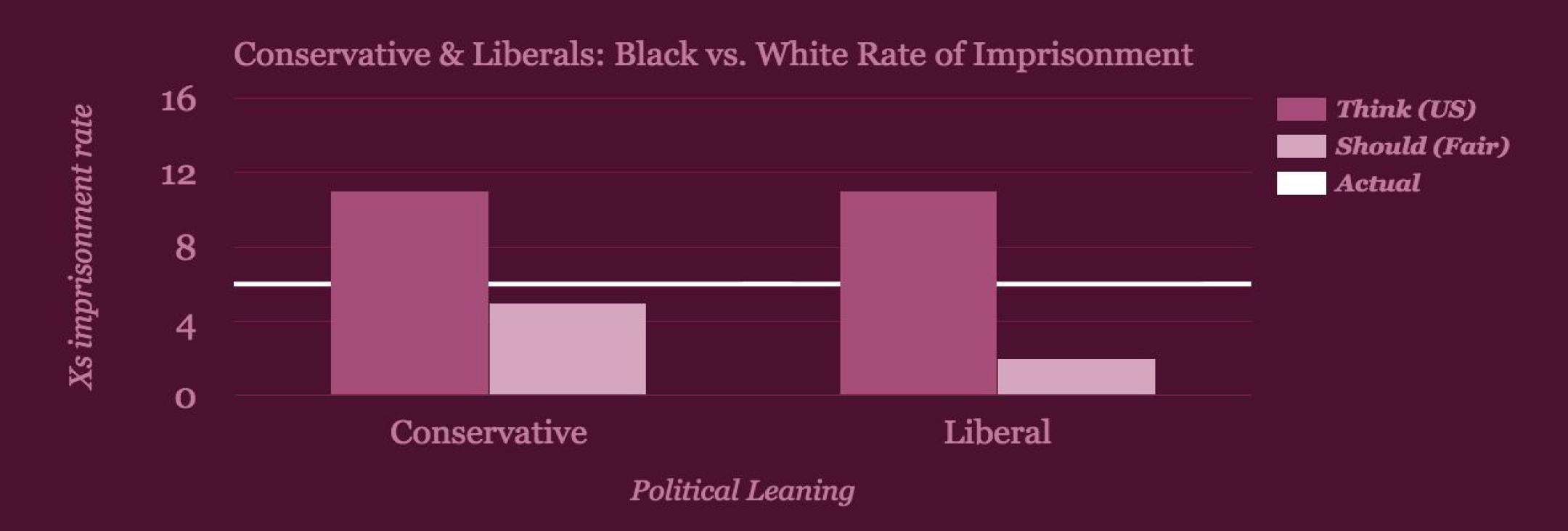

Topic 5 in Fair Game? asked users to think about how much greater the rate of imprisonment is for black versus white men in the US and how much greater it should be in a fair world.

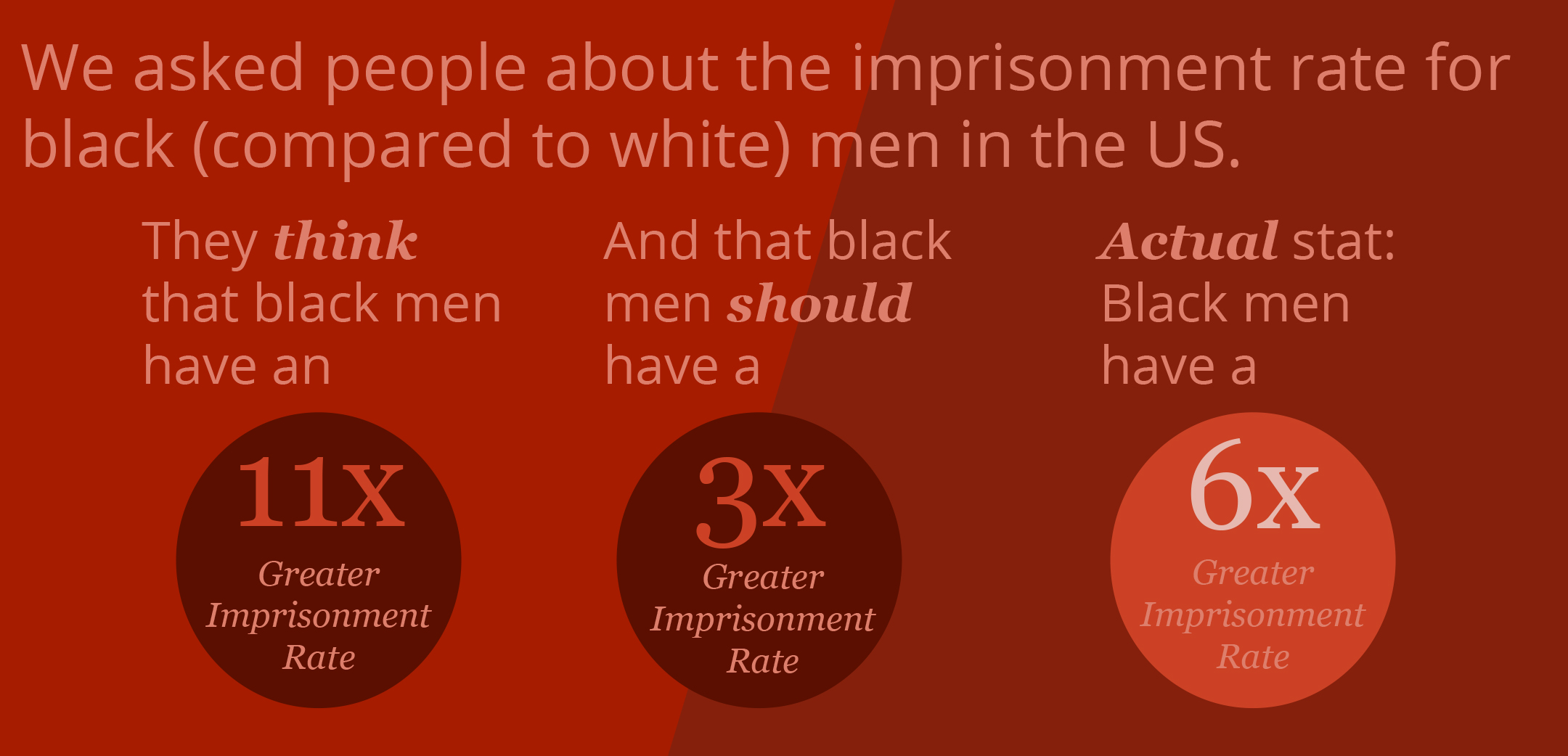

On the whole, our users estimated that black males have an 11x greater imprisonment rate than white males. In reality, recent data shows the imprisonment rate is 6x greater.

How much more greater do people think the imprisonment rate should be in a fair world? 3x more likely.

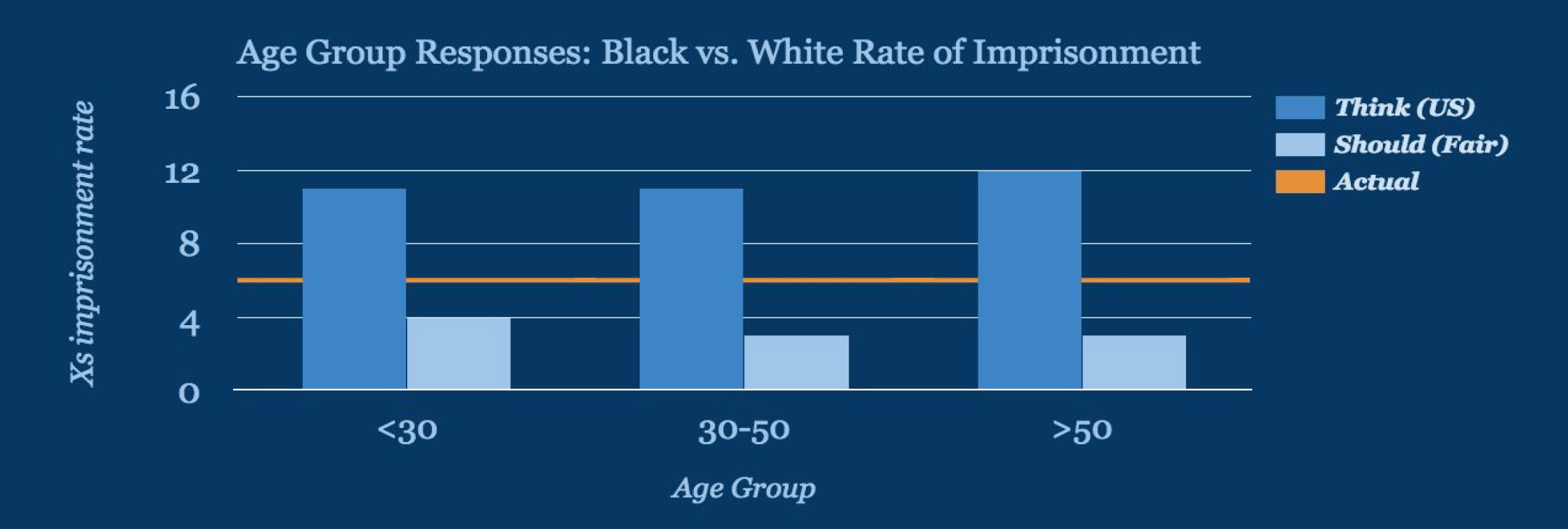

Estimates for the greater likelihood of imprisonment were remarkably similar across all age groups, as were our users’ beliefs about what would be fair.

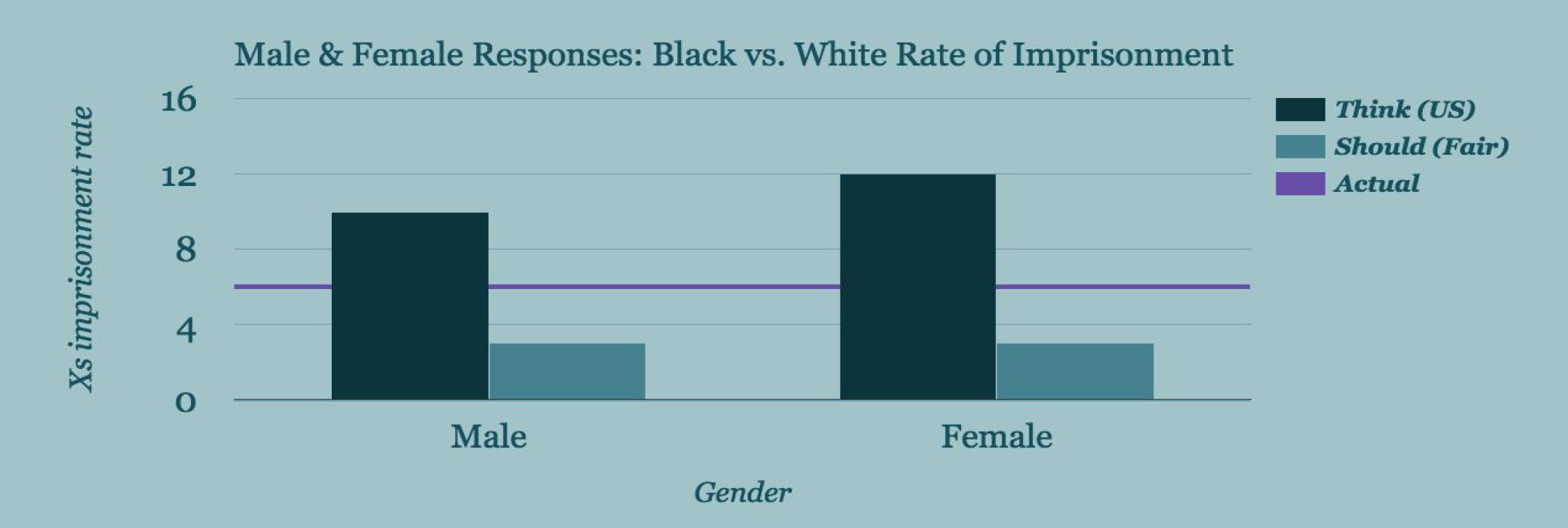

What about gender? Males and females differ in their estimates of the greater rate of imprisonment, estimating 10 and 12 times greater likelihoods, respectively. But they agree in what they think a fair rate would be — 3x.

And political leaning? People who identify as conservative and those who identify as liberal estimate the same (11x) greater rate of imprisonment. In terms of how much greater the rate should be in a fair society, conservatives answered 5x more likely and liberals answered 2x more likely. So although their understanding of the world is similar, their notions of fairness, for this topic, are very different.

Together, the data reported here suggest that people overestimate the gap in the incarceration rate by race. And they would reduce the size of the gap that they perceive. There are many factors that contribute to the racial disparity in imprisonment rate. The so-called War on Drugs may be the single largest factor, with Blacks and Hispanics disproportionately representing those in state prisons for drug offenses and sentenced for federal drug trafficking offenses. These offenses often carry harsh mandatory sentences, further exacerbating the disparities. Discrimination has been shown to be a problem at multiple levels of the criminal justice system, including law enforcement, prosecution, sentencing, and reentry to society.

Beyond the pervasive problem of racial discrimination, another consideration is more purely economic– the growth of private companies building and running prisons. Oliver Hart (a 2016 Nobel prize-winner in Economics) and his coauthors have written about private prison contracts and their tendency to induce the wrong incentives by not focusing on outcomes.

There are economic benefits to reducing the prison population, including reduced costs for taxpayers (construction, maintenance and operation of prisons) and of course income and opportunities for those who would otherwise have been imprisoned. Several states have drug decriminalization ballot initiatives in this year’s election and it will be interesting to see whether these have an impact on the rate of imprisonment in those states. What other possibilities might decrease the prison population and reduce the racial disparity in the rate of imprisonment?

Please join us and play along by downloading Fair Game? from iTunes or Google Play.

Rock the Vote 2016!

Thousands of people are currently involved with getting out the vote. They canvas neighborhoods, stand on street corners, write letters, make calls, and donate money to campaigns. But they rarely know if this has an impact. That’s about to change.

We teamed up with Rock the Vote and VoteRockIt to design and build a new app that allows highly engaged voters to make an impact within their personal networks. The Rock the Vote 2016 app amplifies the motivation and energy of get-out-the-vote volunteers by creating direct links from dedicated voters to their more complacent friends.

Here’s where science comes in. Research has found that simply making a plan can be incredibly effective for actual follow-through. Additionally, letting your friends, family, and co-workers know that voting fulfills a social obligation is something that can serve as an important reminder of their civic duty and generate more interest and involvement going forward.

Interested? Great! We’re here to help you channel your efforts into impacting our democracy, one fence-sitter friend at a time. Become a voter champion by inviting friends in your virtual or local networks to join your team; sign the Rock the Vote pledge, find your polling site, look up the candidates on your ballot, and share posts to your larger social media networks. Most importantly, turn your voting enthusiasm into action-based, goal-driven steps for others. Use the app to encourage your complacent friends to commit to voting, to make a concrete plan, and finally, to share that they’ve actually done it. The power is in your hands.

Download Rock the Vote 2016 for Apple or Android and start the chain reaction today. Use Invite Code ‘10000’ to register as a Voter Champion.

The team that created the app includes Dan Ariely, Julie O’Brien PhD, Steven Prince PhD, Stephanie Tepper, and Allison Waters (Center for Advanced Hindsight), Matt Hudson (app developer and founder of VoteRockit), and the civic tech and policy team at Rock the Vote.

Predictably Irrational App for iPad and iPhone

Thanks for downloading the PI app — you’ve brought it up to the #2 spot in iTunes!!

If you’d like to give the app a review in the app store, I’d very much appreciate it.

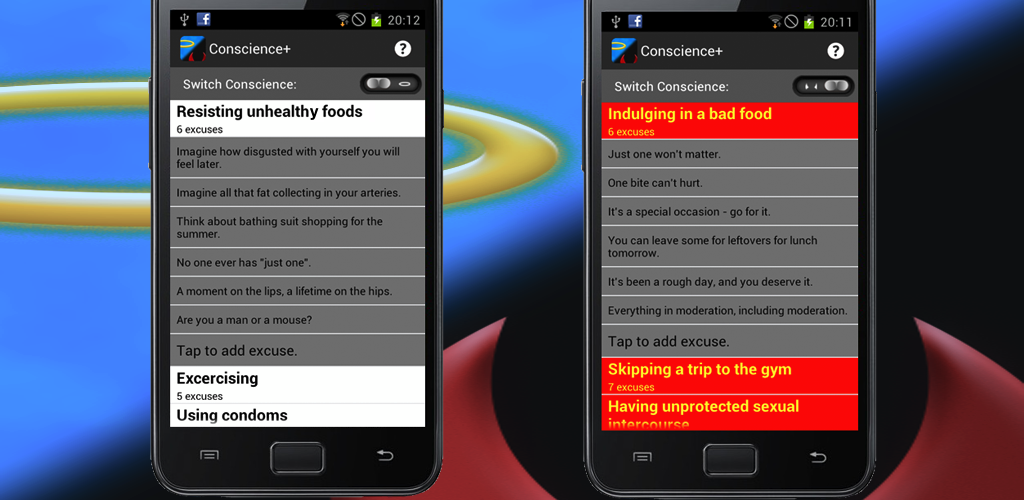

Conscience+ Now Available for Android

The Internet and Self-Control: An App To the Rescue

I have “a friend” who will head over to a coffee shop to get work done. Not because she’s unable to work at her desk or because she needs the presence of other people, but rather because it lets her get away from the Internet and all its distractions.

True, she could easily stay put by just keeping her browser closed. But that requires self-control, and as we all know, keeping ourselves in check is easier said than done. Whatever the resolution (start dieting, start saving, stop procrastinating, etc.) we routinely stick to it for a bit and then cave. We make the resolution in one state of mind – a cool, rational state – and then break it when temptation strikes.

That’s the reason for my friend’s coffeeshop strategy: precommitments allow us to commit upfront to our preferred course of action. In her cool, rational state, my friend can decide not to surf the web and make a point to leave the wireless behind; later, when temptation strikes, she’ll be out of luck. Access denied.

On the whole, I like my friend’s strategy. But there’s a potential problem: what if she needs the Internet to do her work? What then?

Not to worry – there’s an app to the rescue: SelfControl, a free Mac-only software program that blocks access to incoming/outgoing mail servers and websites and was thought up by artist Steve Lambert. (As the son of an ex-monk and an ex-nun, he’s well-versed in self-control.) The app only takes seconds to install and comes with all the flexibility that my friend’s coffeeshop strategy lacks.

Instead of taking leave of the Internet all-together, you can pick and choose what you can and can’t access, and for how long. If Facebook is your particular time-suck, then add its URL to SelfControl’s blacklist and the program will block Facebook and nothing else. If Twitter is another danger zone, then by all means, throw its URL into the mix. Next, figure out how long you want to block them for – anywhere from one minute to twelve hours – and move the slider accordingly. Then press start and you’re good to go.

But here’s the key part: once you click start, there’s no going back. (No wonder the app has a skull and crossbones symbol as its icon.) Switching browsers won’t help you, and neither will restarting your computer or even deleting the app. You won’t get those websites back until the timer runs out. As such, it’s as effective of a precommitment as seeking out a wireless-free zone.

Though temptation routinely deflects us from our long-term goals, our struggle with self-control isn’t a lost cause. Once we realize and admit our weakness, we can do something about it by taking on clever precommitments that save us from ourselves. In an ideal world we wouldn’t need the SelfControl app, but in this world it sure is useful.

Irrationally Yours,

Dan

P.S. For more on precommitments, check out this post on self-control and sex.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like