A Couple Questions

Excuses. Justifications. Rationalizations. Stories. Stretching the truth… So many ways to whitewash the lies we tell ourselves and others. Here are a few questions that might remind you of your own dalliances with dishonesty.

1. What did you say the last time you were running late?

2. Take a look at your desk at home. How many pens and paperclips and so on did you “borrow” from work?

3. How accurate is your online dating profile? How accurate do you think others are?

4. Which e-mail threads would you delete if you knew someone was going to access your e-mail account?

5. Last time someone called you out for misrepresenting something, how did you explain it?

6. What questionable things have you done because “everybody else is doing it?”

7. Which line items on your resume are a bit of stretch?

8. What did you say the last time someone asked how much you weigh?

9. If you opened your mailbox and found a letter from the IRS informing you of an audit, how concerned would you be?

10. Have you ever told someone you never got their voicemail, text, or email?

11. What did you say the last time someone you don’t particularly like asked if you wanted to go to dinner or an event?

12. Speaking of dinner, have you ever said you enjoyed dinner at someone’s house when you didn’t?

13. What do you say when your dentist asks how often you floss?

14. How many haircuts have you claimed to like in the last year? How many did you actually like?

15. What should you be doing instead of reading this blog and answering these questions?

Ask Ariely: A new biweekly Q&A column for the WSJ

I’m going to start taking questions from you, dear readers, deeply ponder them, and send you my responses every other week in the Wall Street Journal.

Read this week’s column, A Double Dip for Voting?, right here. On voting, working, and new experiences.

If you have an interesting question for the column, please email me at: AskAriely@wsj.com

Power and Moral Hypocrisy

When a certain former New York State Attorney General became New York Governor, he pledged to “change the ethics of Albany” and make “ethics and integrity the hallmarks of [his] administration.” Sure enough, he went on to fight collar crime and corruption, reduce pollution and prosecute a couple prostitution rings. Oh, but then the New York Times disclosed that this same law-and-order Governor was patronizing high-priced prostitutes. So much for changing the ethics of Albany.

Power and moral hypocrisy are not strangers – it’s one of the oldest stories around (generally going under the name of hubris), and we see it all the time. But why?

A few social scientists decided to take a stab at finding an answer. Joris Lammers and Diederik A. Stapel (from Tilburg University) and Adam D. Galinsky (from Northwestern University) ran five experiments addressing how morality differs among the powerless and powerful.

They simulated a bureaucratic organization and randomly assigned participants to be in a high-power role (prime-minister) or low-power role (civil servant). The prime-minister could control and direct the civil servants. Next, the researchers presented all participants with a seemingly unrelated moral dilemma from among the following: failure to declare all wages on a tax form, violation of traffic rules, and possession of a stolen bike. In each case, participants used a 9-point scale (1: completely unacceptable, 9: fully acceptable) to rate the acceptability of the act. However, half of the participants rated how acceptable it would be if they themselves engaged in the act, while the other half rated how acceptable it would be if others engaged in it.

The researchers found that compared to participants without power, powerful participants were stricter in judging others’ moral transgressions but more lenient in judging their own: “power increases hypocrisy, meaning that the powerful show a greater discrepancy between what they practice and what they preach.”

Joris and Adam hypothesized that this power-hypocrisy connection was due to the sense of entitlement that comes with positions of power. But what if you took away that entitlement by having participants view their power as illegitimate? In that case, the researchers posited, you would see the power-hypocrisy effect disappear.

To test their idea, they had 105 Dutch students write about an experience in which they were powerful or powerless. But half of the participants were asked to write about a time when they deserved their high or low power (it was legitimate), while the other half were asked to write about a time when they didn’t deserve their high or low power. They then had to rate the acceptability of the bike dilemma from above.

Results: when power (or lack thereof) was legitimate, the powerful also exhibited moral hypocrisy (being less moral themselves but judging others more harshly), while the powerless weren’t – just as before. But when power (or lack thereof) was illegitimate, the powerful didn’t show hypocrisy. In fact, the moral hypocrisy effect not only disappeared but was reversed, with the illegitimately powerful becoming stricter in judging their own behavior and more lenient in judging the others.

Plagiarism and Essay Mills

Sometimes as I decide what kind of papers to assign to my students, I can’t help but think about their potential to use essay mills.

Essay mills are companies whose sole purpose is to generate essays for high school and college students (in exchange for a fee, of course). Sure, essay mills claim that the papers are meant just to help the students write their own original papers, but with names such as echeat.com, it’s pretty clear what their real purpose is.

Professors in general are very worried about essay mills and their impact on learning, but not knowing exactly what essay mills are or the quality of their output, it is hard to know how worried we should be. So together with Aline Grüneisen, I decided to check it out. We ordered a typical college term paper from four different essay mills, and as the topic of the paper we chose… (surprise!) Cheating.

Here is the description of the task that we gave the four essay mills:

“When and why do people cheat? Consider the social circumstances involved in dishonesty, and provide a thoughtful response to the topic of cheating. Address various forms of cheating (personal, at work, etc.) and how each of these can be rationalized by a social culture of cheating.”

We requested a term paper for a university level social psychology class, 12 pages long, using 15 sources (cited and referenced in a bibliography), APA style, to be completed in the next 2 weeks, which we felt was a pretty basic and conventional request. The essay mills charged us in advance, between $150 to $216 per paper.

Two weeks later, what we received what would best be described as gibberish. A few of the papers attempt to mimic APA style, but none achieve it without glaring errors. Citations were sloppy, and the reference lists abominable – including outdated and unknown sources, many of which were online news stories, editorial posts or blogs, and some that were simply broken links. In terms of the quality of the writing itself, the authors of all four papers seemed to have a very tenuous grasp of the English language, or even how to format an essay. Paragraphs jumped bluntly from one topic to another, and often fell into the form of a list, counting off various forms of cheating or providing a long stream of examples that were never explained or connected to the “thesis” of the paper. Here are some excerpts from the four papers:

“Cheating by healers. Healing is different. There is harmless healing, when healers-cheaters and wizards offer omens, lapels, damage to withdraw, the husband-wife back and stuff. We read in the newspaper and just smile. But these days fewer people believe in wizards.”

“If the large allowance of study undertook on scholar betraying is any suggestion of academia and professors’ powerful yearn to decrease scholar betraying, it appeared expected these mind-set would component into the creation of their school room guidelines.”

“By trusting blindfold only in stable love, loyalty, responsibility and honesty the partners assimilate with the credulous and naïve persons of the past.“

“Women have a much greater necessity to feel special.”

“The future generation must learn for historical mistakes and develop the sense of pride and responsibility for its actions.”

At this point we were rather relieved, figuring that the day is not here where students can submit papers from essay mills and get good grades for them. Moreover, we concluded that if students did try to buy a paper from an essay mill, just like us, they would feel that they have wasted their money and won’t try it again.

But the story does not end here. We submitted the four essays to WriteCheck.com, a website that inspects papers for plagiarism and found that two of the papers were 35-39% copied from existing works. We decided to take action with the two largely plagiarized papers, and contacted the essay mills requesting our money back. Despite the solid proof that we provided, the companies insisted that they did not plagiarize. One company even tried to threaten us by saying that they will get in touch with the dean at Duke to alert them to the fact that we submitted work that is not ours (just imagine being a student who had used the paper for a class!).

The bottom line? I think that the technological revolution has not yet solved students’ problems. They still have no other option but to actually work on their papers (or maybe cheat the old fashioned way and copy from friends). But I do worry about the existence of essay mills and the signal that they send to our students. As for our refund, we are still waiting…

Related articles

Looming Integrity Crisis

Apparently, Britons are becoming less honest. At least according to a study conducted at the University of Essex, where several thousand respondents filled out an online survey that repeated questions from a study on citizenship and behavior conducted ten years earlier. According to researcher Paul Whiteley, the purpose of the study was to try to gain an idea of the level of dishonesty in British society, and moreover, what’s considered acceptable and whether that has altered over time.

In the survey, participants were asked to rate various behaviors—such as littering, drunk driving, or having an affair—on a scale from 1 (always justified) to 4 (never justified). What researchers found was that people’s tolerance of certain dishonest behaviors have changed, and almost entirely for the worse. For instance, in 2000, 70% of respondents said having an affair could never be justified, a number that dropped to around 50% of respondents in 2011. And two out of three people said they could justify lying in their own interest. In fact, there was only one behavior that people condemned more in 2011 than in 2000. Perhaps not surprisingly, given that governments the world over have tightened their belts since 2000, that one behavior was falsely claiming benefits.

With this apparent relaxing of moral standards, one might wonder if this is the case across the board. Researchers observed that while women were slightly more honest than men, the most appreciable differences were found among different age groups. Young people were significantly more tolerant of dishonest behavior than older people—for instance, only around 30% of people under age 25 thought lying on a job application was never justifiable as opposed to 55% of people over 65. Neither income level nor education affected levels of honesty.

This is bad news, but the worst part is that over time, if no one counteracts the spread of dishonesty, it is likely to continue. Because we generally look to our peers for cues on what kinds of behaviors are acceptable, if lying on job applications seems to be par for the course, it will increase in frequency. So does this mean that England will be governed by degenerates in a few decades? I guess we’ll see.

Lying Liars Who Believe Those Lies

What do Williams Gehris, America’s most decorated war hero, and Walter Williams, the last Civil War veteran to pass away, have in common?

Both were frauds. They spun tales of military heroism, duped the public, and then – whoops – someone discovered that they hadn’t actually achieved the purported feats. Gehris professed to have racked up 54 decorations, when in reality he had just one. And Williams claimed to have fought in the Civil War, but records prove he couldn’t have because he was only five years old at the time.

I came across these and other military fish tales in the article “Fake War Stories Exposed,” in which Anne Morse covers frauds from all walks of life (journalists, actors, politicians, clergymen) who had all kinds of motives (money, glory, self-aggrandizement). That so many “veterans” could pull the wool over our eyes is remarkable, but what’s even more striking is that many of them seem to have convinced even themselves.

Take for example our decorated war hero from above, Williams Gehris. When a reporter confronted him about his lies, Gehris responded that “there are people who don’t believe 6 million Jews were killed, either.”

Or how about former military chaplain and purported Vietnam veteran Gary Probst? Morse writes that when Probst was confronted about his lies, he claimed that he “lied for the Lord.” Which was to say, his (false) heroics garnered him the trust and admiration of his flock, which ultimately was a good thing.

And then there’s my personal favorite, former Connecticut state representative (and yet another Vietnam faker) Robert Sorensen, who came up with this exquisite response to the disclosure: “For the first time ever, the American public had before them a war in their living rooms… Every single person in this United States fought in that war in Vietnam. We all felt the anguish that those people felt. So in a sense I was there.” Right.

It’s possible, of course, that these conmen fully realized all along what they were doing and only gave their feeble excuses out of a last-ditch effort to save themselves. But given what we know about the power of the mind to self-deceive – how it can rationalize almost anything and rework all kinds of memories – I suspect that many of these men had actually come to view their fibs as truth.

Maybe Lenin was correct when he said: “A lie told often enough becomes the truth.”

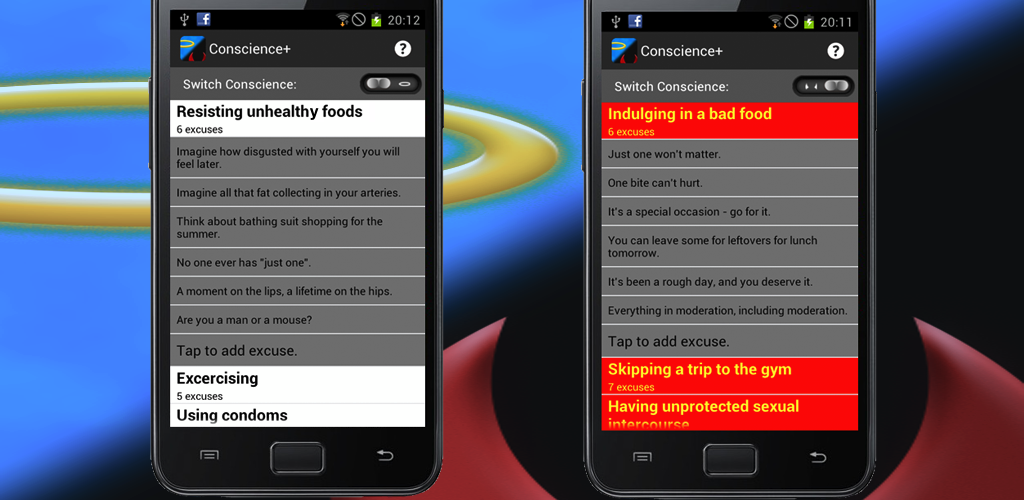

Conscience+ Now Available for Android

Green Consumption: It’s Not All Positive

There was a time when farmer’s markets, eco products, recycling, and renewable energy were squarely in the tree hugger’s domain. Then, somewhere along the line, green went mainstream, turning environmental awareness into a socially desirable trait and a mark of morality.

But is eco-friendliness always a boon? When University of Toronto researchers Nina Mazar and Chen-Bo Zhong recently looked into this, they found that under certain circumstances, green products can license us to act immorally.

Through a series of experiments, Mazar and Zhong drew the following distinction between two kinds of exposure to green: When it’s a matter of pure priming (i.e., we are reminded of eco products through words or images), our norms of social responsibility are activated and we become more likely to act ethically afterwards. But if we take the next step and actually purchase the green product (thereby aligning our actions with our moral self-image), we give ourselves the go-ahead to then slack off a little and engage in subsequent dishonest behavior.

So in effect, a green purchase licenses us to say “I’ve done my good deed for the day, and now I can think about my own self-interest.” I gave $20 to a charity, I pledged support to NPR, I did my share — that sort of thing. How moral we choose to be at any given moment depends not only on our stable character traits but also on our recent behavior.

This implies that if you have two important environmental decisions to make on a given day, your early decision may impact the later one. If you choose a mug over a paper cup for your morning coffee, you may later decide it’s okay not to recycle if a bin isn’t handy. This choice could even affect your subsequent moral choices in other areas, since the moral licensing effect is not domain-specific. (Participants in the above-mentioned experiment, for example, were more likely to cheat and steal cash after making green purchases).

All this to say that we need to think carefully about the unintended consequences of all the decisions we make. While we may consider the consequences of questionable decisions (speeding or parking illegally for example), we rarely consider the effects of “good” ones.

Disclosure? Not Good Enough.

In compliance with a federal integrity agreement, pharmaceutical giant Pfizer released details of its financial involvement with the medical community.

According to the New York Times, the drug maker disclosed that it paid $20 million in consulting and speaking fees to 4,500 doctors in the second half of 2009. The company also shelled out $15.3 million to U.S. academic medical centers for their clinical trials.

A few other drug makers have disclosed their payments to physicians in the past, but this is the first time a company has disclosed its payments for clinical trials. As such, some may see this as a good deed on Pfizer’s part, a noble step towards eliminating or reducing some of the conflicts of interest in medicine.

Only, disclosure doesn’t seem to help. Several studies have shown that when professionals disclose their conflicts of interest, this only makes the problem worse. This is because two things happen after disclosure: first, those hearing the disclosure don’t entirely know what to make of it — we’re not good at weighing the various factors that influence complex situations — and second, the discloser feels morally liberated and free to act even more in his self-interest.

So, in this case the people who run Pfizer will likely feel even more entitled to disregard the public good, and the public, in turn, will not know what to make of the numbers it released. After all, what do you make of the numbers? It’s hard to figure out from a statement of disclosure just how much influence the conflict of interest had on the discloser, and to what degree we should be wary of them as a result.

The real issue here is that people don’t understand how profound the problem of conflicts of interest really is, and how easy it is to buy people. Doctors on Pfizer’s payroll may think they’re not being influenced by the drug maker — “I can still be objective!” they’ll say — but in reality, it’s very hard for us not to be swayed by money. Even minor amounts of it. Or gifts. Studies have found that doctors who receive free lunches or samples from pharmaceutical reps end up prescribing more of the company’s drugs afterwards.

It’s just a fact of human life: we are compelled to reciprocate favors, and an ingrained inability to disregard what’s in our financial interest. As author Upton Sinclair said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

Teachers, Cheating, and Incentives

In recent years there seems to have been a surge in academic dishonesty in high schools. No doubt this can be explained in part by 1) increased vigilance and reporting, 2) greater pressure on students to succeed, and 3) the communicable nature of dishonest behavior (when people see others do something, whether it’s enhancement of a resume or parking illegally, they’re more likely to do the same). But, I also think that a fourth, and significant, cause in this worrisome trend has to do with the way we measure and reward teachers.

To think about the effects of these measurements, let’s first think about corporate America, where measurement of performance has a much longer history. Recently I met with one of the CEOs I most respect, and he told me a story about when he himself mismanaged the incentives for his employees, by over-measurement. A few years earlier he had tried to create a specific performance evaluation matrix for each of his top employees, and he asked them to focus on optimizing that particular measure; for some it was selection of algorithms, for others it was return on investment for advertising, and so on. He also changed their compensation structure so that 10 percent of their bonus depended on their performance relative to that measure.

What he quickly found was that his top employees did not focus 10 percent of their time and efforts on maximizing that measure, they gave almost all of their attention to it. This was not such good news, because they began to do anything that would improve their performance on that measure even by a tiny bit—even if they caused problems with other employees’ work in the process. Ultimately they were consumed with maximizing what they knew they would be measured on, regardless of the fact that this was only part of their overall responsibility. This kind of behavior falls in line with the phrase “you are what you measure,” which is the idea that once we measure something, we make it salient and motivational. In these situations people start over-focusing on the measurable thing and neglect other aspects of their job or life.

So how does this story of mis-measurements in corporate America relate to teaching? I suspect that any teachers reading this see the parallels. The mission of teaching, and its evaluation, is incredibly intricate and complex. In addition to being able to read, write, and do some math and science, we want students to be knowledgeable, broad-minded, creative, lifelong learners, etc etc etc. On top of that, we can all readily agree that education is a long-term process that sometimes takes many years to come to fruition. With all of the complexity and difficulty of figuring out what makes good teaching, it is also incredibly difficult to accurately and comprehensively evaluate how well teachers are doing.

Now, imagine that in this very complex system we introduce a measurement of just one, relatively simple, criteria: the success of their students on standardized tests. And say, on top of that, we make this particular measurement the focal point of evaluation and compensation. Under such conditions we should expect teachers to over-emphasize the activity that is being measured and neglect other aspects of teaching, and we have evidence from the No Child Left Behind program that this has been the case. For example, we find that teachers teach to the test, which improves the results for that test but allows other areas of education and instruction (that is, those areas not represented on the tests) to fall by the wayside.

And how is this related to dishonesty in the school system? I don’t think that teachers are cheating this way (by themselves changing answers, or by allowing students to cheat) simply to increase their salaries. After all, if they were truly performing a cost-benefit analysis, they would probably choose another profession—one where the returns for cheating were much higher. But having this single measure for performance placed so saliently in front of them, and knowing it’s just as important for their school and their students as it is for their own reputation and career, most likely motivates some teachers to look the other way when they have a chance to artificially improve those numbers.

So what do we do? The notion that we take something as broad as education and reduce it to a simple measurement, and then base teacher pay primarily on it, has a lot of negative consequences. And, sadly, I suspect that fudging test scores is relatively minor compared with the damage that this emphasis on tests scores has had on the educational system as a whole.

Interestingly, the outrage over teachers cheating seems to be much greater than the outrage over the damage of mis-measurement in the educational system and over the No Child Left Behind Act more generally. So maybe there is some good news in all of this: Perhaps we now have a reason to rethink our reliance on these inaccurate and distracting measurements, and stop paying teachers for their students’ performance. Maybe it is time to think more carefully about how we want to educate in the first place, and stop worrying so much about tests.

(This post also appeared as part of a leadership roundtable on the right way to approach teacher incentives in the Washington Post. The Washington Post will post more opinions about this topic here. )

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like