Thanks for Giving

Ask Ariely: On Pointless Gaming, Topics and Teachers, and Getting Over It

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I waste about two hours each day playing stupid games on my iPhone. It feels so innocent, but it actually makes me lose focus at work and takes up time I should be spending with my wife and kids. Do you have an idea for how I can ditch this bad habit?

—Arianna

One way to fight bad habits is to create rules. When you start a diet, for example, you can set yourself a rule such as “I won’t drink sugary beverages.” But to be effective, rules need to be clear and well defined. For example, a rule such as “I will drink only one glass of wine a day” is unlikely to work. With this type of rule, it is not clear what size of glass we are talking about, or if we can drink more today and reduce our drinking next week. In essence, if the rule is not clear-cut and unequivocal, we are likely to break it while deceiving ourselves that we are actually following it.

In your case, you could decide that, from now, on you won’t be playing the iPhone between 6 a.m. and 9 p.m. And to help you follow this rule, you should let your loved ones know. Or you could set up game bans for weekdays or working hours. Good luck.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am in middle school, and there is one topic in school I really love and one I really dislike. There is also one teacher I really love and one teacher I am not very excited with. Would I be better off if the teacher I love taught the topic I love, and the duller teacher taught the topic I dislike? Or would I be better off if the teacher I love taught the topic I dislike, and the duller teacher taught the topic I love?

—Tima

What you are really asking me about is the accumulation of pleasure and pain. On the one hand, you might argue that having one class with a great teacher and a great topic, and one class with nothing going for it, would give you at least one class to look forward to. You might also argue that, if a class isn’t going to be good, it doesn’t really matter how bad it is—adding a good teacher to a bad topic, for example, wouldn’t help much.

On the other hand, you might argue that a class with a bad teacher and a bad topic is going to be too much to bear. In this case, the combined pain might pass your tolerance threshold and color the entire semester.

I should say, first, that I am delighted you like some of your teachers and topics, and I don’t want you to stop thinking of school as joyful. But I do think that the mixing approach would be better for you.

I suspect that having a class with a bad teacher and a bad topic will be too much for you to handle. And I suspect that in the class with the teacher you love and the topic you don’t, you will learn to focus on the teacher and pay less attention to the topic, while in the class with the teacher you dislike and the topic you love, you will learn to focus on the material and pay less attention to the teacher.

I wish you many years of joyful (or at least not torturous) learning.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What do you think is the best psychological approach to getting over a girlfriend? Should you cut off seeing her completely? Continue getting together for coffee, etc.?

—Jason

I suggest that you cut it off completely. Meeting an old girlfriend over and over, while wondering if you should have ended things or not, is just going to prolong the pain—and without any real value.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Feeling Gypped, Dishing out for Wine, and Dressing Down

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am the president of a local union that represents many federal workers. We are dealing with an interesting complaint stemming from the days during the government shutdown when employees were furloughed. Staffers who were furloughed are getting back pay for the days they were off, and because of this the employees who were designated as exempted from the furloughs (who originally felt special about their status and contribution) now feel gypped: Some of them expressed feeling like “a fool for working while others got to stay home.” Any advice?

—Robert

The current approach is clearly the wrong way to design paybacks after a furlough. Since we are likely to experience more government shutdowns in the years to come, maybe we should have a strategy for handling such situations.

I would suggest creating small groups composed of both furloughed and exempt employees and letting each furloughed worker decide how much of their back pay he or she is willing to contribute to the exempt workers in that group. A lot of research shows that people care to some degree about the welfare of others and about fairness, and we do so even at a cost to our own pocket. This kind of social utility should get the furloughed employees to act fairly, and they are even likely to be extra fair if the amount that they would give is going to be posted publicly and contribute to their reputation.

It’s possible that the government at some point will step in and do something to correct the issue. But while this local approach won’t completely fix the problem, it should make the distribution of income more equitable and, just as important, increase camaraderie among employees.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I love drinking good wine. Each time I go to a restaurant I wonder what is the ideal amount of money to spend on a bottle. What do you do?

—John

A recent experiment suggests an answer. Ayelet and Uri Gneezy from the University of California, San Diego, teamed up with a winery owner in their state to figure out, experimentally, the best price for his Cabernet. On some days they sold the wine for $10, on others for $20 or $40. Demand fell off at $40, but the winery sold more bottles of its Cabernet when the price was $20 than $10. On top of that, the customers who paid more indicated that the wine tasted better!

Uri and John List describe that experiment in their new book “The Why Axis,” in which they use field experiments as a method to look at many of life’s questions, from wine to love to the workplace. Their main advice is that we should all do more experiments.

So, the next time that you go to a restaurant, order two glasses of the same varietal of wine, one rather basic and one fancy, and tell the waiter to write down which is which and not to tell you. Then see if you can tell the difference. Of course, trying this experiment with just two wines is bad science, because you could be correct by chance, so you need to repeat the experiment many times. My guess? Your ability to tell the price difference will be indistinguishable from random guesses.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I recently watched your presentation at a professional conference and was wondering why an Israeli guy telling Jewish jokes is wearing an Indian shirt?

—Janet

In general I am not someone who should be asked for fashion tips, but this might be an exception. I like to dress comfortably, but in many professional meetings there is a code of uncomfortable dress: suits. My solution? I figured that as long as I am wearing clothes from a different culture, no one who is politically correct would complain that I’m underdressed. After all, the critics could be offending a whole subcontinent. Now that I think about it, maybe I should start giving fashion tips.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Help me name this documentary!

I have been working on a documentary about cheating with Salty Features for a while now, and I am looking for the best title for the film. And who better to ask than you?

If you’d like to help me name this documentary, please take the survey here. It should only take you about 2 minutes to complete, and I very much appreciate your help.

Thanks!!

Irrationally Yours,

Dan Ariely

Ask Ariely: On the Lottery, Corporate Charity, and Maternalism

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A strange thing happened to me a few days ago. One of my employees came into my office holding a few lottery tickets and asked, “You in? It’s 45 bucks.” I never play the lottery, but I felt an inexplicable urge to say yes–and I did. Was I being grossly irrational?

—Itay

You were indeed irrational, but in a very common way. Usually, when you are considering whether or not to buy a lottery ticket, you take into account how your life would change if you won and contrast this with the cost of the ticket and the slim chance of winning. After making this quick computation, you decide not to buy a ticket.

But when another person asks you to “go half” with them on a tickets that they’ve already purchased, another factor comes into play: regret. Now you can’t help thinking how you would feel if that other person won. You quickly conclude that it would make you feel terrible and you also realize that you would keep on thinking about this forgone fortune for a very long time.

I think that too many people are currently losing too much money on various lotteries (often state sponsored), and I wouldn’t want more people to keep losing money this way. But if I were looking for a way to get more people to gamble, I would certainly try to play on our capacity for regret.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

On a recent flight, the attendants declared it was “Breast Cancer Awareness” month and asked for donations from the passengers for this worthwhile cause. I give to a multitude of breast-cancer organizations, but this approach offended me. Maybe if the airline had offered to match my contribution dollar for dollar it would have made me feel we were partnering in this effort, but the way it was handled just annoyed me. Is it just me or were they doing this the wrong way and actually hurting the cause they are trying to help?

—Rob

I suspect that many companies trying this approach to corporate responsibility don’t get much of a boost from it in terms of internal morale or customer loyalty. It turns out that companies get the most credit for donating to charity in two cases: One is when they give first and then tell the customers, “Look, we’ve already given on your behalf, now you can contribute as well.” The second is when they empower their customers to give themselves (“here is a $5 voucher for you to give to any organization you value”). The approach you describe, where the company simply says, “We have a charity that we like and want you to give to it,” is ineffective in every way.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

It seems to me that any reading of social science research implies that we are all less capable in making our own decisions and that as a consequence we need help. Yet, it seems that Americans are emotionally against any hint of paternalism. Any idea how we can overcome this barrier?

—Tom

I agree with your general position. I think that part of the problem is that, while we see irrationalities and bad decision-making in those around us, we don’t see these mistakes as readily in our own behavior. Because of this partial blindness, we are not as interested in limiting our freedom to make our own stupid decisions. I’m not sure what we can do to fix this part of the problem. But perhaps we can think about how to market paternalism in a better way. As a first step, I would change the term and call it maternalism. After all, who could object to listening to a mother figure?

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

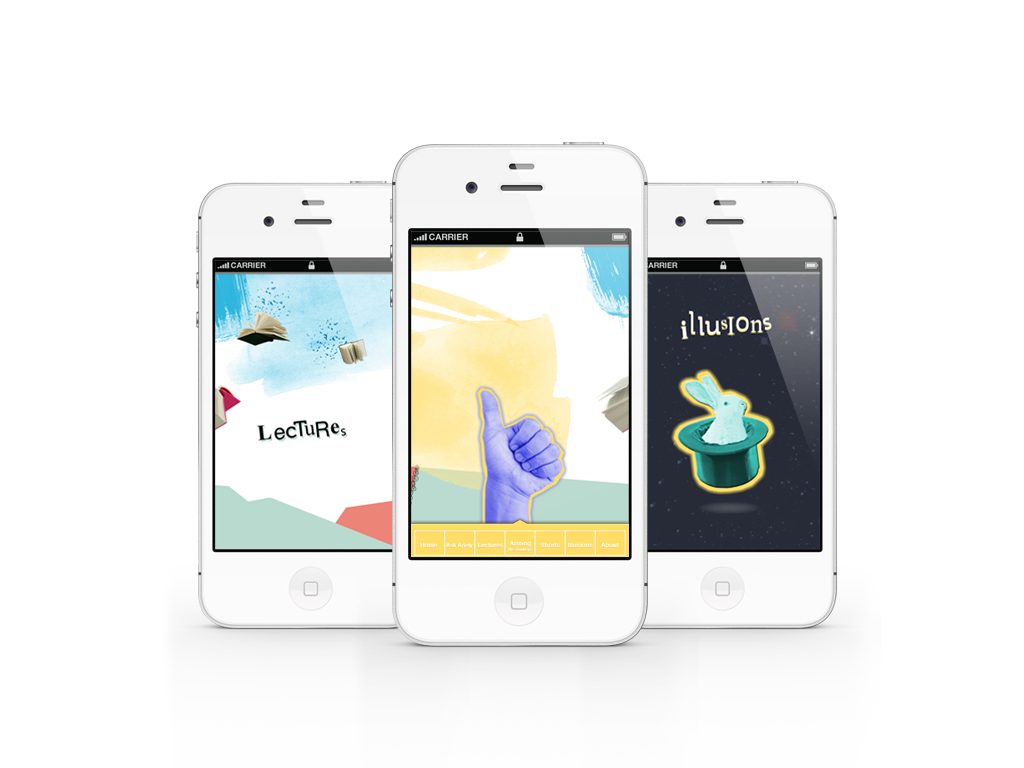

Introducing Pocket Ariely – the greatest app ever created!

What can you do with Pocket Ariely?

READ! life-changing advice from a “genius at understanding human behavior” [James Surowiecki, staff writer at The New Yorker and author of The Wisdom of Crowds], and never make another bad decision!

WATCH! lectures and entertaining videos from “one of my heroes” [George Akerloff, 2001 Nobel Laureate in Economics], and never let anyone else make a bad decision either!

LISTEN! as a man described as “surprisingly entertaining” [USA Today] interviews the leading scientists of the day, and learn everything there is to know about humanity!

LOOK! at visual illusions that will twist your brain into knots, and remind yourself of your own irrational tendencies wherever you are!

TASTE! the culinary confections of a man widely acknowledged as the finest improvisational chef in three states, and never go hungry again! (Well, not really…)

With Pocket Ariely in your pocket, you can take me with you wherever you go. You’ll be happier (since you’ll never make another bad decision), healthier (since you’ll never make another bad decision), wealthier (since you’ll never make another bad decision) and wiser (yes, you guessed it: since you’ll never make another bad decision). We almost guarantee it!

Why spend $5 on an app? Think about how much you pay for one latte or one beer. Or how much money you waste on things you don’t need. Just think: you could improve your life forever by saving your lunch money and bringing a salad to work just once. Your waistline may thank you, too! But most importantly, think about how the purchase of this app will help the blossoming field of behavioral economics. All profits from this app will be put toward the research being conducted at my lab, the Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University.

Thank you in advance for helping our research, and I hope you enjoy what Pocket Ariely has to offer.

Irrationally Yours,

Dan

Watch our Pocket Ariely teaser and trailer, too!

Download now on your iPhone, iPad, and Android devices!

And check out the talented team of developers that made this app at mezzolab.com

Ask Ariely: On Tesla, To-Do Lists, and Knowing the News

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I was thinking about buying a Tesla electric car, and I was very excited about it, but given the recent news, I am not sure this is a wise decision. Is it too risky?

—Karl

Indeed, earlier this month a Tesla Model S drove over a large metal object, and the object punched a hole through the plate protecting the battery, and the battery pack caught on fire. But this is only one part of the story. In August, the model S received five stars in all test categories—an unusually high rating—by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. In the two days after we all learned about the crash test ratings, the stock of the company went up by 2%.

We now need to add one more data point to this body of evidence: The fire happened on Oct. 1. The share price fell by 10% over the next two days. By the way, this means that the effect of one small piece of bad news can be four times more effective than good news based on much more data. (A rare downgrade of the stock by the R.W. Baird brokerage from “outperform” to “neutral” probably also contributed to the drop.)

Elon Musk, Tesla’s CEO, pointed out in a statement Oct. 4 that no one was hurt, that the car warned the driver to pull over, and that gas cars are in no way safer. After the statement, the stock price increased by 3%, making the overall losses 6.2% from the day before the accident.

From a psychological perspective, this overreaction to one very salient (and very sad) accident is nothing new. It is a consistent way that we react to salient news, and it is perfectly irrational.

And after all of this, my suggestion to you? If you had decided to buy a Tesla before this accident, get one now—because the event didn’t add much to the information you used to make your original decision. In fact, given that other people might have an irrational fear of buying a Tesla, maybe the prices will go down a bit.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why do people love to write to-do lists?

—Joe

I suspect there are rational and irrational reasons for the very large amount of list-making activity we see around us. On the rational side, lists help us with faulty memory and allow us to share tasks with other people simply and efficiently. On the irrational side, making lists and checking items off these lists give us the false sense that we are actually making progress. The term for this by the way is “structured procrastination.” It’s an attempt to capture the momentary feeling that we are progressing—whereas in fact when we look back at the end of the day on what we achieved, we realize that we did not get much done. I also suspect that all the apps that help us make lists and then make it fun for us to check things off are reducing our collective productivity, by replacing real work and focus with structured productivity.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am always upset by bad news online when I turn on my computer. But negative news is pervasive, so what can I do to make myself feel better and get down to work immediately?

—Liz

One approach is to start each day with the most depressing set of news around for about five minutes and then move to the regular news. The idea here is that contrast between the highly depressing and the regular will make you feel good in comparison.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Wasted Time, Framing Failure, and Matrimonial Gambling

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Often when I meet with a group of my closest friends, the discussion goes something like this: “Where do you want to go?” “Not sure.” “Where do you want to go?” “Not sure.” Etc. These discussions are frustrating and waste time. Any advice on how to move them forward and get to a decision faster?

—Matthew

When someone asks “What do you want to do tonight?” what they often are saying implicitly is: “What is the most exciting thing we can do tonight, given all the options and all the people involved?”

The problem is that figuring out the best solution is very difficult. First, we need to bring to mind all the alternatives, next our preferences and the preferences of the people in the group. Then we have to find the one activity that will maximize this set of constraints and preferences.

The basic problem here is that, in your search for the optimal activity, you are not taking the cost of time into account, so you waste your precious time asking “What do you want to do?”—which is probably the worst way to spend your time.

To overcome this problem, I would set up a rule that limits the amount of time that you are allowed to spend searching for a solution, and I would set up a default in case you fail to come up with a better option. For example, take a common good activity (going to drink at X, playing basketball at Y) and announce to your friends that, unless someone else comes up with a better alternative, in 10 minutes you are all heading out to X (or Y).

I would also set up a timer on your phone to make it clear that you mean business and to make sure that the time limit is kept. Once the buzzer sounds, just start heading out to X (or Y), asking who wants to come with you and telling everyone else that you will meet them there. After doing this a few times, your friends will get used to it and perhaps bring an end to this wasteful habit.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’d like to understand something I see in my own life and in billion-dollar companies: the switch from aiming to succeed to aiming not to fail. You see this in companies such as Microsoft, but even the National Aeronautics and Space Administration went from the ambitious 1960s-’80s era to its current conservative program. What can we do to overcome this problem?

—Alex

Assuming this is indeed a generalized pattern (and it would be interesting to collect data on the question), it might be a simple outcome of the endowment effect: basically, once we own something, we get used to it and are very reluctant to see it go away. When you are just starting out, you have nothing, so you look at potential gains and losses to some degree on an equal footing. But once you experience some success, you start thinking more carefully about what you have, and you don’t want to give it up, so you become much more conservative. In the process, you give up the things that made you successful from the get-go. Nor are companies alone in this: I suspect that the tendency to switch to a do-nothing defensive posture is just as common in the behavior of our public officials and governments.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Someone once said to me that marriage is like betting someone half of everything you own that you’d love him or her forever. Do you agree?

—Shane

From the perspective of an outside observer, there are some things in life that can be described as a bet or a gamble—while for the people directly involved, looking at it that way will be a very bad idea. Marriage is one of these cases. It might be fun and interesting to think about other peoples’ marriages in such terms, but don’t be tempted to think about your own relationship this way. And certainly don’t mention these odds to your significant other.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Economic Drinking Games, Regulating Relationships, and Wedding Ring Woes

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m turning 30 in December, and I want to have a “nontraditional” celebration. I’m thinking about re-creating some economics experiments at my party.

Here’s the plan: Lots of alcohol and yummy appetizers at a fancy place here in Dallas. Computers scattered across the room with small apps, each running a different experiment. After all, how many parties do you go to where you get to have fun, have too much to drink and learn something about economics? Any advice?

—Virginia

I really love your idea—and here is a suggestion for an experiment relating to dishonesty. Give each of your guests a quarter and ask them to predict whether it will land heads or tails, but they should keep that prediction to themselves. Also tell them that a correct forecast gets them a drink, while a wrong one gets them nothing.

Then ask each guest to toss the coin and tell you if their guess was right. If more than half of your guests “predicted correctly,” you’ll know that as a group they are less than honest. For each 1% of “correct predictions” above 50% you can tell that 2% more of the guests are dishonest. (If you get 70% you will know that 40% are dishonest.) Also, observe if the amount of dishonesty increases with more drinking. Mazel tov, and let me know how it turns out!

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My daughter started dating a lazy, dumb guy. How can we tell her gently that he is wrong for her without preaching to her, causing her to ignore us or go against our advice?

—Concerned Mother

It seems that you are experiencing the same reaction most mothers around the world have toward their daughters’ boyfriends. Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that you are, in fact, correct, and that your daughter’s new boyfriend really is dumb, lazy and up to no good. Nevertheless, don’t tell your daughter your opinion and instead ask her questions. Naturally, people tend not to ask themselves certain questions. But if someone else asks them, these questions get planted in their minds, and it is hard to keep from thinking about them. So thoughtful questions can make people think differently about what they want and how they view the world around them.

For example, you can ask, “How do you and your boyfriend get along? Do you ever fight? What do you love about him? What do you like less about him?” I admit it’s a bit manipulative, but I hope it will get her to think about her relationship in more depth. And maybe she will reach the same conclusions you have.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My wife-to-be really wants to get a two-carat ring, but I’d rather get a smaller ring and spend the rest of the money for future expenses—house, wedding, etc.

Her view is that most of her friends have big rings, plus she’s been dreaming about this for a long time. What do you think about this irrational behavior? Any advice?

—Jay

First, there is a difference between irrational and difficult to understand, and for sure it is irrational to call your future wife irrational in public. If you get her a ring, realize that comparison to her friends is part of the game you are buying into and try to get her a ring that will make her happy with this comparison.

At the same time, what if you could switch to a different jewelry category—maybe a wedding necklace or bracelet? In this case comparison will not be as clear, and you could probably get away with spending much less.

Finally, has it occurred to you that she may want this so much because you are so against it?

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Audiobooks, Idle Waiting, and Public Transportation

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

From time to time, people around me discuss a book they have read recently. While I know the book well, and I want to participate in the conversation, I hesitate because I listened to the book on tape. My first question is why am I embarrassed to say that I listened to the book? My second question is what can I do about it?

—Paula

We learn how to listen and comprehend at a young age and therefore we don’t really remember how difficult it was for us. On the other hand, we learn how to read and write at a later age and we all remember the difficulty of the early struggles with reading and writing. Because of that, people associate greater difficulty with reading than listening. As a consequence, we take greater pride in reading than listening.

My first suggestion is that you realize that it isn’t necessarily the case that reading is more difficult. It’s just that we forget how difficult it is to learn to comprehend. When I got your question I purchased an audio book and I listened to it on a long flight–and for what it is worth, I find it is harder to focus when listening to a book than when reading one.

A second suggestion is that you to find a different word to describe your experience. For example, for books you loved, maybe you can say: “I inhaled that book.” For more difficult books, maybe you can say: “I struggled with it,” or some other phrase.

If these don’t work, perhaps it is time to change the meaning of the word “read.” Maybe we should acknowledge that today there are many ways to get information — audiobooks being one of them. This might seem dishonest, but you might be able to start a revolution, and help lots of people who listen to audiobooks feel more comfortable with what they’re doing. Good luck!

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I noticed that when I drive around the block looking for parking I spend a lot of time too far away from my destination (I live in Chicago, and hate the cold), so instead, I just wait until somebody leaves and take the spot. It proved to be more efficient, but my friends can’t seem to stand it, and I can’t do it when I’m not alone in the car. My question is why my friends find in intolerable waiting for someone to leave.

—Danny

The phenomenon you’re encountering is aversion to idleness. There was a story a while ago about an airline that tried to optimize which carousel that the luggage would come out of. There was an engineer with this airline that realized that some carousels were close to some gates, and others were close to other gates. He wrote an algorithm to try to figure out which carousels to send the luggage to so that it would be closest to where the plane was landing. Before this algorithm was created, travelers would get out of the plane, walk for a while and get to the carousel. Sometimes it was such a long walk that their luggage was waiting for them already, and they would pick it up and go home. In the new system, the carousel was much closer and people would walk a little bit, find the carousel and wait for their luggage. People hated this new system because they were standing in one place to wait for their luggage. This idleness was so unpleasant that people complained and the airline rejected this algorithm. My understanding is that they have not gone the whole way in the reverse and tried to get the luggage in the farthest carousel possible, but maybe it is something they are still working on.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Many people justify evading paying for public transportation by rationalizing that “public transportation services aren’t value for money,” that “it’s a victimless crime,” and that “as a tax paying passengers, we’ve already paid for my journey once.” Do you have any advice on counteracting these rationalizations?

—Julian

Make these people buy some shares of the public transportation company.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like