Summer Internship

Dear Friends,

Please pass this announcement on to undergraduate and graduate students who may be interested in applying to the Center for Advanced Hindsight’s first annual summer internship in behavioral science research. More information can be found below and here.

———————————————————————————————-

The Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University is accepting applications from students interested in conducting experiments in behavioral economics in our summer research internship. The 5-week program begins on July 7, 2011 and ends on August 11, 2011. For more about the CAH team at the Center for Behavioral Economics, see http://becon.duke.edu.

From studies on the consumption vocabulary of vegetables to the effect of eye gaze on trust, there is never a dull moment in the Center for Advanced Hindsight. The CAH summer internship will be valuable for students who are interested in gaining experience with experiments in behavioral economics. Our lab includes researchers with training in social and cognitive psychology, behavioral economics, marketing, design, and general judgment and decision-making. Interns will spend approximately 20 hours each week working in collaboration with CAH research assistants, faculty and graduate students and will be involved with planning and conducting experiments in the lab and field, as well as some data entry and analysis. At the end of the five weeks, interns will propose a project of their own (a 2-page report) stemming from the research they carry out over the summer.

Interns will be provided with a stipend to cover living expenses, with details to be determined.

To apply, please submit the following as a single pdf by April 20, 2011:

1. A resume or curriculum vitae. Please include your university, major, relevant courses, research experience, GPA, and email address.

2. A one-page cover letter describing your research interests, as well as your specific areas of strength and weakness. What experience do you have with the behavioral sciences? Why would you like to attend the program, and what do you hope to gain from your internship experience?

3. A letter of reference from a member of your academic community (a graduate student, post-doctoral researcher, or professor).

Materials (and any questions you may have about the internship) should not be sent to me, but should be submitted to advancedhindsight@gmail.com

FAQs and further information can be found here.

Applicants will be notified of their status by May 20, 2011

Dan

Backing Down From Agreements–Results

Imagine that you are shopping for a car, find a seller, and agree to purchase his car in a couple of days. The day before the sale, you find a better deal on a different car. Under what conditions would you renege on your original agreement? Would it be easier if your original agreement was made, so over the phone? Or over coffee?

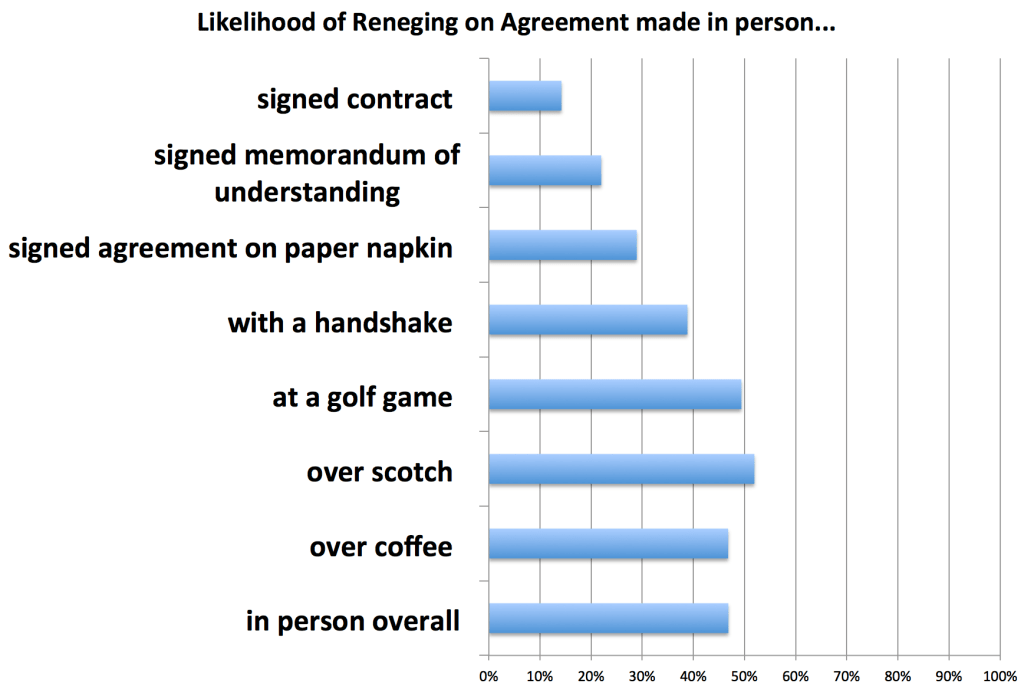

Last week we put out a survey to find out, and here are the results:

As you can see, people have the hardest time reneging on deals made in person (compared with phone and email), and we have much less of a problem reneging deals made via a car dealer relative to one that was mediated by a mutual friend.

Zooming in on in-person agreements, we see here that agreements made over scotch and golf seem most likely to be reneged on, whereas we see significant improvement over various, even rudimentary, forms of signed contracts (napkin).

So next time you’re out selling a car, make sure at least to bring a napkin and pen with you, and next time you’re out buying a car, don’t sign anything unless you absolutely have to!

p.s here is an interesting academic paper related to this topic

Admitting to another irrationality

My own worst enemy: procrastination and self-control

My problem with “Just Say No”

One of the main difficulties I face on a daily basis is an inability to say “no.” Sometimes my difficulties bring me back to the song in Oklahoma! Where Ado Annie sings “I’m just a girl who can’t say no,” and it looks to me that I’m basically like her (granted, she and I are responding to quite different propositions). I have always had this problem, but it used to be that nobody really asked much from me, so this weakness didn’t pose a real problem. But now that behavioral economics has become more popular, I receive invitations to speak almost every day. Accordingly, my inability to say “no” has turned into a real challenge.

So why do I (and I suspect many others) suffer from what we might call the “Annie” bias? I think it is because of three different reasons:

1) Avoidance of regret: Regret is a very interesting, uncomfortable feeling. It is about not where are, but where we could be. It is too easy to imagine that things could have been better. Imagine, for example, that you missed your flight either by two minutes, or by two hours: under which of these conditions would you be more upset? Most likely, you will feel more upset if you missed your flight by two minutes. Why? After all, your actual state is the same: in both cases you are stuck at Newark for five hours waiting for the next flight, watching the same news report on CNN, responding to email on your smartphone, and munching on expensive and not very good food. They key is that having missed your flight by just a few minutes, you continuously think about all the things you might have done to get on the plane on time – leaving the house five minutes earlier, checking your route to avoid traffic jams, and so on. This comparison to how things could have been, and the feeling of “almost” makes you miserable. By contrast, a two-hour delay is not as upsetting because you don’t make these kinds of regretful, “woulda, coulda, shoulda” comparisons. (Comparing your current state to some other idealized one, by the way, is a huge source of general unhappiness, especially when comparing yourself to your likeminded peers.)

Now think of a circumstance in which you don’t feel regret at the moment, but want to avoid feeling regret in the future. Let’s say you are buying an expensive new flat-screen TV. As you are whipping out your credit card to pay for it, the salesperson offers you an extended warranty for an additional 10% off the sticker price. You don’t relish the thought of paying more for this extended warranty, but the salesperson asks you to imagine how would you feel if, six months down the road, the TV stopped working and you had passed on the opportunity for the extended warranty. To make the moment even more salient, the salesperson adds that the offer is only available to you now (and only now!). With this final push, you go ahead and purchase the extended warranty – paying a premium in order to avoid the possibility that in the future you will hit yourself over the head and tell yourself that you should have purchased the extended warranty when you had the chance.

What has all this got to do with my own inability to say “no”? My version of the extended warranty is that I get invited to all kinds of stimulating conferences and meetings in amazing places, with interesting people. And the invitations always feel as if they are my only chance to see that particular place and meet those particular people.

2) The curse of familiarity: I suppose I also suffer from a form of the “identifiable victim effect” that I described in Chapter 9. As you recall, when a problem is large, general and abstract, it is easy for us to turn our heads away and not care too much about it. But when the problem is close to home our emotions are evoked, and we are more likely to take action. Similarly, when I receive formal invitations from people I don’t know, it is relatively easy to politely turn down their offer. But when I receive invitations from people I do know, even if only superficially, it’s a different story altogether. And the better I know someone, the harder it is to say “no, sorry, you know I would really love to come, but I just can’t.”

One of the clever ways I attempt to deal with this version of the identifiable victim effect is to ask my wonderful assistant Megan to say no for me in the cases where I have to do so. This way, I don’t have to feel the pain of saying “no”, and because she is not saying “no” for herself, she has a much easier time with it than I do.

3) The future is always greener: I also find that it’s easier to say “yes” to things in the future, particularly the distant future. If someone asks me to come to an event in the next month or two, I generally have no choice but to say “no” because I’m either traveling or fully booked — there’s just no space in my schedule. [I have to admit that sometimes when someone asks me to come to an event and my calendar says that I’m already booked, I feel relieved.] But when someone asks me to do something in a year, my calendar naturally looks far emptier. (Of course, the feeling that I will have lots of extra time in the future is just an illusion – my life will likely be just as full of myriad, often unavoidable things. It’s just that the details aren’t filled in yet.

The basic problem is this: when we look far into the future, we assume that the things that are limiting and constraining us in the present won’t be there to the same degree. For me, I somehow imagine that meetings with students and administrators and colleagues, not to mention reviewing papers and so on, won’t be part of my daily life eight months in the future.

My friends Gal Zauberman and John Lynch, who have done research on this topic, recently gave me some interesting advice. They suggested that I imagine every single event I’m asked to attend will occur exactly four weeks from the present. With this exact schedule I mind, I should then ask myself whether I find it important enough to squeeze it in or cancel something else. If the answer is “yes,” then I should accept the invitation; but if my answer is “no,” I should pass. This is easier said than done, and I have not yet been able to consistently cultivate this frame of mind, but I am starting to adapt this mindset.

Perhaps what I need is to add some technological aid to Gal and John’s advice. What if I had an advanced calendar application made just for people who have a hard time admitting out how busy they will be in the future? Ideally, such an application would take all my meetings and travel from a given period and, based on that schedule, simulate what my time would look like in a year. This would allow people like me to respond to requests in a more realistic, less hopeful way. Perhaps this advanced calendar application is something I should start working on in a few months…

***

Thankfully, my own irrationalities tell me that there is still a lot of room for research and improvement.

Irrationally yours

Dan

A rather longish study

I just posted a rather longish new study (should take about 15 min).

So — if you have the extra time and you are willing to tell us about the way you view different moral decisions Please look on on the right under “Participate” and press on the “Right Now. Take a quick anonymous survey” link

I will post the results in a few weeks

Thanks in advance

Dan

The Magic of Natural

Our recent studies of medications labeled “natural” have yielded some interesting findings. First, most people prefer medications that are natural to medications that aren’t natural. Secondly, and perhaps most surprisingly, people do not see natural medications as being more effective than non-natural medications at attacking the disease at hand. So why do they prefer natural? It turns out that many people believe that natural medications have fewer unintended consequences in both short time and long term side effects. This stems from popular belief, sometimes called “caveman theory,” that our bodies are attuned for diets that were common thousands of years ago and thus might not react well to newer, synthetic products. Hopefully new, exciting research will shed light on the consequences, both positive and negative, of these beliefs.

Gold

Cars, iPhones, and Incentives to Work

A few centuries ago little luxuries like iPhones and cars did not exist for the working class to consider buying, so the motivation to work did not extend beyond the desire to feed oneself and one’s family. Now, however, we can imagine that with cars and iPhones within reach, even lower wages in the face of higher taxes are offset by the motivation to acquire these items. The market for such consumer luxuries, in turn, has inspired an incredible wave of motivation and innovation, so let’s be thankful for them.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KrvhvXzAz3s?w=425&h=349]

We have a fun new study…

In Praise of the Handshake

Imagine that you and I meet at a party, and I tell you about my research on behavioral economics. You see opportunities to use the principles to improve your business and think we could work together. You have two options: You can ask me to collaborate, with a handshake promise that if things work out, you’ll make it worth my while. Or you can prepare a contract that details my obligations and compensation, specifies who will own the resulting intellectual property, and so on.

For most of you, the decision is obvious. The second approach, the complete contract, is the way to go. But should it be?

The idea of making a deal with a handshake—what we generally call an incomplete contract—makes most of us uncomfortable. A handshake is fine between friends, but when it comes to vendors, partners, advisers, employees, or customers, we believe that incomplete contracts are a reckless way to do business.

Indeed, firms try to make contracts as airtight as possible—specifying outcomes and contingencies in advance, thus lowering the chances for misunderstanding and uncertainty. But complete contracts have their own flaws, and business’s increasing dependence on (I would say, fetish for) absurdly detailed contracts in every situation comes with its own downside.

All contracts deal with the direct aspects of the expected exchange and with unexpected consequences. Incomplete contracts lay out the general parameters of the exchange (the part that we shake hands over), while the unexpected consequences are covered by social norms governing what is appropriate and what is not. The social norms are what can motivate me to work with you, and what would establish goodwill in resolving problems that might arise.

As for complete contracts, they too specify the parameters of an exchange, but they don’t imply the same adherence to social norms. If something is left out, or if circumstances change, there’s no default to goodwill—it’s happy hunting season for all. When we use complete contracts as a basis for working together, we take away flexibility, reasonableness, and understanding and replace them with a narrow definition of expectations. That can be costly.

A CEO of a large internet company recently told me about one of the worst decisions of his career. He instituted a very specific performance-evaluation matrix that would determine 10% of his employees’ compensation. Before this, the firm, like most, had a general agreement with its employees—they had to work hard, behave well, and were measured on certain goals. In return they were rewarded with salary increases, bonuses, and benefits. This CEO believed he could eliminate the uncertainty of the incomplete contract and better define ideal performance.

The complete-contract approach backfired. Employees became obsessively focused on meeting the specific terms of their contracts, even when it came at the expense of colleagues and the company. Morale sank, as did overall performance.

Even lawyers see the risks of complete contracts. As part of my research, I asked the dean of Duke’s law school, David Levi, if I could take a look at the school’s honor code. Expecting a detailed contract written by lawyers for lawyers, I was shocked to find that the code went something like this: If a student does anything the faculty doesn’t approve of, the student won’t be allowed to take the bar exam. It was, in essence, a handshake agreement!

“Imagine that a student decides to deal drugs and raise chickens in his apartment,” Levi said. “Now suppose that our code of conduct bans many activities but doesn’t address pot or chickens. The student has honored the code. But does Duke really want that student to become a lawyer?”

Complete contracts are inevitably imperfect. So what’s better: a complete contract that mutates goodwill into legal trickery, or an incomplete contract that rests on the understanding we share of appropriate and inappropriate behavior?

This post first appeared on HBR

Three Valentines Day Tips

Tip #1: Go for the chocolate and flowers.

While a rational economist would tell you and your special Valentine to skip the formalities of jewelry, chocolate, and flowers (after all, don’t we all really have better things to spend our money on?), we know that in reality, human relationships are based on more than money.

This video also appeared on my friend Paul Solman’s website

Tip #2: Be careful. Kids are expensive.

Toys, Nintendo, iPads, clothes, birthday parties: kids are expensive. Be careful.

Tip #3: Don’t let your expectations run away.

Our data show that our expectations about people we meet online tend to be overinflated. If we see that somebody is into sports, for example, we tend to mistakenly assume that they like the same sports we do. This bias, as you can imagine, can lead to emotional distress after the date. Keep your expectations modest.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like