Spider-man & Overcommitment

The Irrationality of Organizational Escalation: The Danger of Spider-man & Overcommitment

By Henry Han-yu Shen

Spider-man: Turn Off the Dark is an upcoming rock musical featuring music and lyrics from U2’s Bono and The Edge and originally directed by Julie Taymor, best known for the hit musical The Lion King.

This musical is also the most expensive Broadway production in history, with a record-setting initial project budget of $52 million. The show’s opening has been repeatedly delayed while the production cost continues to accrue, currently totaling a whopping 70 million dollars. The final estimated budget approaches 100 million dollars, with no guarantee of profit return and below-average reviews.

Spider-man’s situation exemplifies a classic case of organizational failure. Marked by producers’ continuously irrational contributions of monetary support to a seemingly hopeless project. In many ways this case is similar to the failed Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant program as analyzed by Ross and Staw (1993). The Shoreham project also experienced an escalation of project cost – from an initial $75 million to the final cost of $5 billion – and it a classical example of how organizations become increasingly committed to losing courses of action over time.

We can draw several parallels by comparing the Spider-man Broadway production to organizational escalation. We can see that economic data alone cannot easily deter organizational leaders from withdrawing from a full-scale course of action, especially in cases involving something that is highly subjective in its value (such as a Broadway production). When we consider that the cost of production for Spider-man continues to rise, the initial psychological over-commitment of the producers can become even stronger. Such forces appear to have come into play, trapping the producers into a losing situation while they continue to throw money into the project. It is important for future producers, or any organizational leaders, to keep in mind the existence and properties of these different types of escalating determinants in order to avoid clouded judgment and behavior when making decisions.

Rapture Me Not

On my drive to Asheville, NC this past weekend, I passed a multitude of billboards like the one below. According to multimillionaire Harold Camping, tomorrow is Judgment Day. You may have heard.

The idea of imminent rapture piqued my interest, so I looked into the matter, filling my brain with more than I ever wanted to know about the mathematically-inclined radio broadcaster and his cult of hopeful followers.

Although Camping’s 1994 doomsday prediction (clearly) turned out to be false, he has no doubts that this time he is on the right track. And why not? As you can see, the bible guarantees it! The alleged proof in favor of tomorrow’s rapture not only comes from the bible, but also from “indisputable” evidence in the form of devastating natural disasters and war, technological advances, economic crises, global governments…and, of course, the rise of the gays.

However, I’ve compiled a list of my own — a compendium of evidence in support of the impending demise of humanity:

- The Great Mississippi Flood

- The Sky is Falling

- Paris Hilton has a new reality show

- Sarah Palin has a NYT bestseller

- Extrasensory Perception (ESP) exists

- Touchdown Jesus is struck

- Kate and William postponed their honeymoon

- Charlie Sheen is no longer winning

- Obama becomes a US citizen

- Osama liked porn

- And, most notably, at this very minute I find myself wearing jeggings

Enjoy the rapture tomorrow, and have a lovely Sunday

~Aline Grüneisen~

Upside of Irrationality: Paperback!

The Upside of Irrationality has been released today in paperback! To celebrate this occasion, I will be releasing videos over the next few months — each discussing one of the chapters.

Here is a look into the introduction:

p.s I just learned that the world is going to end on May 21, so if you want to get the book, do it quickly (and pay with a credit card).

irrationally yours

Dan

Wait For Another Cookie?

The scientific community is increasingly coming to realize how central self-control is to many important life outcomes. We have always known about the impact of socioeconomic status and IQ, but these are factors that are highly resistant to interventions. In contrast, self-control may be something that we can tap into to make sweeping improvements life outcomes.

If you think about the environment we live in, you will notice how it is essentially designed to challenge every grain of our self-control. Businesses have the means and motivation to get us to do things NOW, not later. Krispy Kreme wants us to buy a dozen doughnuts while they are hot; Best Buy wants us to buy a television before we leave the store today; even our physicians want us to hurry up and schedule our annual checkup.

There is not much place for waiting in today’s marketplace. In fact you can think about the whole capitalist system as being designed to get us to take actions and spend money now – and those businesses that are more successful in that do better and prosper (at least in the short term). And this of course continuously tests our ability to resist temptation and for self-control.

It is in this very environment that it’s particularly important to understand what’s going on behind the mysterious force of self-control.

Several decades ago, Walter Mischel* started investigating the determinants of delayed gratification in children. He found that the degree of self-control independently exerted by preschoolers who were tempted with small rewards (but told they could receive larger rewards if they resisted) is predictive of grades and social competence in adolescence.

A recent study by colleagues of mine at Duke** demonstrates very convincingly the role that self control plays not only in better cognitive and social outcomes in adolescence, but also in many other factors and into adulthood. In this study, the researchers followed 1,000 children for 30 years, examining the effect of early self-control on health, wealth and public safety. Controlling for socioeconomic status and IQ, they show that individuals with lower self-control experienced negative outcomes in all three areas, with greater rates of health issues like sexually transmitted infections, substance dependence, financial problems including poor credit and lack of savings, single-parent child-rearing, and even crime. These results show that self-control can have a deep influence on a wide range of activities. And there is some good news: if we can find a way to improve self-control, maybe we could do better.

Where does self–control come from?

So when we consider these individual differences in the ability to exert self-control, the real question is where they originate – are they differences in pure, unadulterated ability (i.e., one is simply born with greater self-control) or are these differences a result of sophistication (a greater ability to learn and create strategies that help overcome temptation)?

In other words, are the kids who are better at self control able to control, and actively reduce, how tempted they are by the immediate rewards in their environment (see picture on left), or are they just better at coming up with ways to distract themselves and this way avoid acting on their temptation (see picture on right)?

It may very well be the latter. A hint is found in the videos of the children who participated in Mischel’s experiments. It’s clear that all of the children had a difficult time resisting one immediate marshmallow to get more later. However, we also see that the children most successful at delaying rewards spontaneously created strategies to help them resist temptations. Some children sat on their hands, physically restraining themselves, while others tried to redirect their attention by singing, talking or looking away. Moreover, Mischel found that all children were better at delaying rewards when distracting thoughts were suggested to them. Here is a modern recreation of the original Mischel experiment:

A helpful metaphor is the tale of Ulysses and the sirens. Ulysses knew that the sirens’ enchanting song could lead him to follow them, but he didn’t want to do that. At the same time he also did not want to deprive himself from hearing their song – so he asked his sailors to tie him to the mast and fill their ears with wax to block out the sound – and so he could hear the song of the sirens but resist their lure. Was Ulysses able to resist temptation (the first path)? No, but he was able to come up with a very useful strategy that prevented him from acting on his impulses (the second path). Now, Ulysses solution was particularly clever because he got to hear the song of the sirens but he was unable to act on it. The kids in Mischel’s experiments did not need this extra complexity, and their strategies were mostly directed at distracting themselves (more like the sailors who put wax in their ears).

It seems that Ulysses and kids ability to exert self-control is less connected to a natural ability to be more zen-like in the face of temptations, and more linked to the ability to reconfigure our environment (tying ourselves to the mast) and modulate the intensity by which it tempts us (filling our ears with wax).

If this is indeed the case, this is good news because it is probably much easier to teach people tricks to deal with self-control issues than to train them with a zen-like ability to avoid experiencing temptation when it is very close to our faces.

*********************************************************

* Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez MI (1989) Delay of gratification in children. Science. 244:933-938.

** Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Houts R, Poulton R, Roberts B, Ross S, Sears MR, Thomson WM & Caspi A (2011) A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth and public safety. PNAS. 108:2693-2698.

Re: Wedding Advice

Hello, it’s the anonymous PhD again, back to report what the wisdom of the crowd was on our wedding-planning dilemma. First, I’d like to thank Dan’s readers for your excellent comments. Matt and I really appreciate your thoughtfulness.

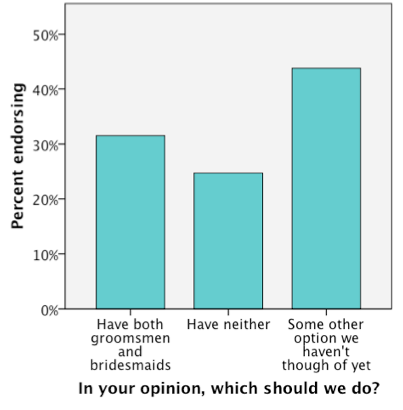

As the graph illustrates, of the two options I presented, having attendants won out, but not overwhelmingly. However, the most popular response was to propose a third option. The most common of these were:

- Have one of Matt’s bothers stand on my side, and the other on his side.

- Have no attendants, but give Matt’s brothers some other role of honor, such as giving toasts or readings.

- Have only groomsmen, and I should not worry what people infer about me.

Now it’s time to let you in on why I was asking for wedding advice on a blog about rationality and decision making. One motivation was that Dan and I were curious whether Matt’s “wanting” attendants carried more weight than my “not wanting” them. Many people (55%) said they simply chose the option they themselves prefer, or based on considerations of what is normal/typical (33%) or costly/effortful (31%). But, some (28%) did say that “wanting” is more important than “not wanting”. While I understand that feeling, I can’t figure out if it’s rational. What do you think?

Dan and I also wondered what people’s answers reveal about how they think people should resolve impasses like this. By far, the most common principle mentioned was that people in a relationship should take turns getting their way when it comes to big impasses. So, in our case, the idea was that since I conceded to Matt’s desire to have a big wedding, he should in turn concede to my desire not to have attendants.

But, we saw some very different principles advocated too, namely:

- People should not take turns getting their preferred outcome – scorekeeping and adversarial thinking are hurtful (though, an alternative method was not explicitly suggested).

- “Halfway” compromises (in this case, for example, a big wedding but no attendants) leave everyone unhappy – a couple should go all the way with one person’s preferences in a given situation.

Personally, one principle that stuck with me (and Matt, too) was brought up by the first commenter, Francesca: that what both of us should be doing is asking, “What will make this wedding great for the other person?” rather than concerning ourselves with our own interests. I thought this was very wise advice.

For those who are interested, we have ultimately decided to have my three sisters stand up as bridesmaids, and my brother, along with Matt’s brothers, stand up as groomsmen. Having just siblings as attendants avoids the political intricacies of picking friends, and Matt has offered to pay for the bridesmaids’ dresses (since my sisters are broke college students) as well as coordinate the fittings. My siblings are much more tradition-minded than I am, and they’re excited to be a part of the wedding.

Dishonest Drunks

When you think about behavioral science research, the image that probably comes to mind is that of laboratories, computers, surveys, electrodes, and maybe even rats — but you may not realize the amount of research conducted in the field. At the Center for Advanced Hindsight we certainly do our share of lab research, but we also like to shake things up and occasionally target the unsuspecting participant in their favorite local setting. For instance, you might find us at a popular eatery, your favorite independent bookstore, a busy shopping center, a science fair, or even driving around in our fancy research mobile.

When you think about behavioral science research, the image that probably comes to mind is that of laboratories, computers, surveys, electrodes, and maybe even rats — but you may not realize the amount of research conducted in the field. At the Center for Advanced Hindsight we certainly do our share of lab research, but we also like to shake things up and occasionally target the unsuspecting participant in their favorite local setting. For instance, you might find us at a popular eatery, your favorite independent bookstore, a busy shopping center, a science fair, or even driving around in our fancy research mobile.

On one of our latest excursions, we ventured out to Franklin Street, a hot spot for many Chapel Hillians to have a drink (or a few) and a good time. When the night was upon us we set out to answer the question: are you more likely to cheat when you’re drunk?

So we set up two research stations and waited for the bar crawlers to crawl. As the night progressed we surveyed the bar, recruiting bar-goers of varying drunkenness. Participants, many with drink in hand, played a 15-minute computer game that was designed to test their honesty. The game was a simple task where participants chose to pay themselves more or less money based on their choices in the game, and of course some of their decisions turned out to be more honest than others. We visited a wide array of bar scenes from the local band crowd to the underground pool players, the 90’s hip hoppers, the indie rockers, and even the Carrborites — and we found the same thing.

Our data shows a low to moderate correlation between cheating and drunkenness, which may suggest that the more alcohol you consume the more dishonest you become. Were the participants actually more dishonest? One could argue that perhaps that they were less capable of completing the task while intoxicated. Of course, we’ll need to keep looking into the possibility. And you can, too. Next time you are out with some friends, you might want to take a few minutes and conduct an “experiment” on your own.

~Jennifer Fink~

FN LN

Physician-Assisted Suicide and Behavioral Economics

By Arjun Khanna

As the American population ages, the debate about the ethics of physician-assisted suicide for terminal patients becomes more important.

Proponents of legalizing of physician-assisted suicide argue the practice is ethically justifiable because it can alleviate prolonged physical and emotional suffering associated with debilitating terminal illness. Opponents claim that legally sanctioned lethal prescriptions might destroy any remaining desire to continue living – a sign of society having “given up” on the patient.

Ultimately, these arguments rest on differing opinions regarding the effect of this policy on the patient’s wellbeing. The challenge, then, is to determine how legalization of physician-assisted suicide would affect the wellbeing of terminally ill patients and their medical decision-making.

Outside of philosophical arguments, examination of an interesting finding regarding physician-assisted suicide – know as “The Oregon Paradox” – can add an interesting dimension to the debate. The paradox is the finding that when terminal patients in Oregon receive lethal medication (under Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act), they often feel a sense of greater wellbeing and a desire to live longer. In 2010, of 96 patients requested lethal medication, only 61 actually took it. Even more interesting are the many anecdotal accounts of terminal patients, upon receiving lethal medication, that feel a surge of wellbeing and a desire to persevere through their illness.

Why is this this the case? Looking at this question from an expected-utility perspective suggests that given the option to terminate their own life, terminal patients will decide how long they want to live by comparing the value they expect to gain from the rest of their lives to the expected intensity of their suffering. At the point where future utility is expected to be negative – that is, when the patient’s condition becomes so intolerable that living any longer is not worth the cost – the patient would choose to end life if the option were available.

The critical point from this perspective is that patients choose the amount of time they are willing to continue living with their illness, which will depend how quickly they deteriorate. If the rate of deterioration is slower than expected, then patients should delay terminating their lives; if the rate of deterioration is faster than expected, patients should desire to end their lives quicker.

But now let us say that patients have been prescribed lethal medication and have the option of ending their lives at any point of their choosing. As before, patients don’t want to choose a time too soon or too distant, but with the power to control the end of their lives they no longer have a reason to err on the side of haste! The patients can now wake up every day with the comfort of knowing that they do not have to suffer through pain or stress they might find intolerable.

Being given the option to determine the time of our own death can transform patients from powerless victims of their illness to willing survivors of it. Together, the importance of feeling in control and the ability to reduce (but not eliminate) uncertainty about rate of deterioration adds an interesting new dimension to the underlying ethical debate and seems to provide credence to the benefits of legalized physician-assisted suicide.

It is clear is that we need a greater understanding of the decision-making of patients at the end of their lives, and that with this improved understanding we can construct policy to better protect their wellbeing (for an interesting recent movie on this topic see “How to Die in Oregon”).

———————–

References:

Lee, Li Way, 2010. “The Oregon Paradox” Journal of Socio-Economics. 39(2):204-208.

Turman, S.A., 2007. The Best Way to Say Goodbye: A Legal Peaceful Choice at the End of Life. Life Transitions Publications.

May brings more than flowers

How the Start of a Month Changes Everything (or seems that way)

How the Start of a Month Changes Everything (or seems that way)

A couple days ago, we took advantage of the changing of the months to run a series of studies on people’s confidence in achieving their closely approaching goals.

We asked them questions about how successful they felt they would be in reaching their goals tomorrow and in the next few days and how different things would be. For some, we subtly reminded them of the upcoming May 1st.

We found that the reminder of “May” made people think that they and others would be far more successful. This was controlling for gender, level of current struggling, importance of the goal, and previous contentment with goal progress. And we looked at both specific and general sets of goals.

Why? Calendar boundaries show how relatively irrelevant boundaries can drastically change how we compartmentalize events (For an example of how statelines can ‘prevent’ earthquakes see here). In this instance, a simple reminder of the upcoming month does not lead people to think that they themselves will change a lot but that the externalities that have recently been in their way will wane.

An Upside to Irrationality?

So how should we view this new finding? Are people being rational, irrational, or strategically irrational? We know from tons of research that people ignore base rates and make egregious forecasting errors about their life.

I think that this is an upside to irrationality. The new month gives us the opportunity to refocus and pre-commit to our goals through new gym memberships or a trip to an organic grocery store (I just signed up for an organic vegetable/fruit/bread delivery service, which I highly recommend). Furthermore, these temporal boundaries fill us with self-efficacy, which have been shown to be positively related to accomplishing goals.

Industries of self-help could take advantage of these boundaries and possibly create more “meaningless” boundaries to help motivate their clients.

Irrational or not, putting the past in the past is a great way to motivate us in the present. May your May be full of success!

~Troy Campbell~

Wedding advice

Wedding planning: A case study in joint decision making

By an anonymous PhD

My fiancé, Matthew, and I are currently planning our wedding, an absolute adventure in joint decision making. I am learning that even though I am a decision researcher, I know surprisingly little about how to make decisions with another person.

Since both of us greatly value autonomy, in the past if we have had different preferences, we’ve simply done our own thing. For example, one afternoon while vacationing at Arches National Park last summer, Matt wanted to go on a 7-mile hike, and I wanted to read by the hotel pool. So, we went our separate ways and did precisely what we each wanted.

But, that doesn’t really work out in the wedding domain. Obviously, I can’t say, “Well, you can have a big fancy wedding, I’m going to elope.” Thus, we recently find ourselves repeatedly gridlocked.

Some background: I am not a fan of weddings in general, and my own is no exception. I don’t like the pomp and circumstance, I don’t like the symbolism behind a lot of the traditions, and I think it’s a silly thing to spend many thousands of dollars on. Matthew, on the other hand, is much more sentimental than I am, in a surprising bit of gender-role reversal. He values the ritual of weddings, and it’s important to him to have a large audience of his friends and family there.

So, while I would prefer to have a small handful of people at a justice-of-the-peace style affair, we’re planning a traditional wedding and reception for 150 guests because it is important to Matthew, and Matthew is important to me. Fine – one bit of joint decision making solved.

But: one decision point has not been so easily solved. Matt wants to have attendants (i.e., groomsmen, bridesmaids) so that his brothers can be his groomsmen; Matt was a groomsman at his brothers’ weddings, and thinks his brothers will feel honored at being selected. But, I really don’t want to have attendants, I think because it’s such a clear marker of a typical, traditional wedding. Plus, I then have to choose bridesmaid dresses, theme colors, and the actual bridesmaids (the politics of which are arguably much more complicated when choosing female attendants vs. males).

One option we entertained was to have groomsmen but no bridesmaids, but this is unpalatable because I’m worried that everyone will infer that no one would be my bridesmaids. This appears to be a win-lose sort of endgame, rather than those nice win-win solutions exhorted by the negotiation books I’ve read, and I don’t see a way around that. So, the options apparently are:

a) have both groomsmen and bridesmaids

b) have neither

Dan proposed that I use his blog as a forum to ask for advice. So, readers, which of the two options would you advise us to do, and how did you come to that conclusion? Or, are there other win-win options we haven’t thought of?

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like