April: That time of year when the weather is perfect and the mosquitoes have yet to emerge full swarm. When you can start to think about lying by the pool without fully having to come to terms with wearing a bathing suit in public….

…And yet it’s that time of year when the majority of the country will be gripped by stress as that fateful day moves ever closer – April 15th, tax day.

No one likes cutting a check to Uncle Sam, and the fact that the process of filling out the tax forms resembles a nightmarish (Choose-Your-Own-Adventure) story does nothing to improve matters. But as is often the case, the anticipation is arguably the worst part, and typically one dedicated night (in addition to a more substantial amount of time taken to organize) is sufficient to finish the paperwork. It’s just a matter of convincing yourself to sit down and do it.

But what if it wasn’t such a dreadful experience? Imagine how the tax experience would change if you had a way to alleviate the stress and maybe even enjoy some of the aspects of the task at hand…

Let’s say that your 1040 came with a little extra stuff: maybe a container with an alcohol content, or perchance something of the chocolate persuasion. What if your tax forms arrived in a gift box with some financial documents on the side? What if the instructions for filling out the form told you to type in your personal information and take a bite of chocolate, type in your W-2 information and drink some of the alcohol, add your deductions and try some of the nuts etc? What if we could live in a world where you actually looked forward filling out these forms?

What do you think? Would you be interested in doing something like this on this tax season?

If you don’t mind, click this link and let me know what you think about this idea.

Irrationally yours

Dan

We’ve seen numerous examples of how companies create an illusion of free choice when in fact they want us to choose one option over the other. The power of defaults takes advantage of our laziness and fear of making any changes when it comes to making complex, difficult, or big decisions.

Hitler seems to have had a few of these tricks up his sleeve as well, as seen here in this 1938 voting ballot:

Translation: “Referendum and Großdeutscher Reichstag; Ballot; Do you agree with the reunification of Austria with the German Reich that was enacted on 13 March 1938 and do you vote for the party of our leader; Adolf Hitler?; Yes; No”

Wealth Inequality in America

Perform the following thought experiment. Remove yourself for a moment from your present socioeconomic circumstances and imagine that you are to be replaced randomly into society at any class level.

Now, before you know your particular place in society you are told that it is within your powers to redistribute the wealth of that society in any way that you choose. What distribution would you choose? This famous thought experiment is the basis of political philosopher John Rawls, as outlined in his highly influential 1971 work, “A Theory Of Justice,” in which he argues that the lowest class should be made as well off as possible. But this of course assumes that we all come to the same conclusion when we perform the thought experiment ourselves. To test this, Mike Norton and I recently conducted a study in which we asked Americans to first guess at the distribution of wealth in the United States, and then we asked them to perform the thought experiment and lay out what they think would be the ideal distribution of wealth if they were to enter society and be placed randomly in a class.

Here is what we found:

As you can see from the figure, participants rather badly estimated the current state of wealth disparity! Furthermore, they offered an ideal wealth distribution (under a “veil of ignorance”) that was even more different (and more equal) relative to the current state of affairs.

What this tells me is that Americans don’t understand the extent of disparity in the US, and that they (we) desire a more equitable society. It is also interesting to note that the differences between people who make more money and less money, republicans and democrats, men and women — were relatively small in magnitude, and that in general people who fall into these different categories seem to agree about the ideal wealth distribution under the veil of ignorance.

Maybe this suggests that when there are no labels, and we think about the core of our morality in abstract terms (and under the veil of ignorance), we are actually very similar?

In Chile last June, I had the opportunity to spend some time with Felipe Kast, the new government’s minister of planning, and a few of his compadres. (We also went dancing, but that is another story.) One of the topics we talked about was the Chilean retirement saving plan.

By law, 11% of every employee’s salary is automatically transferred into a retirement account. Employees select their preferred level of risk, with the following restrictions: They may not choose either 100% equities or 100% bonds, and the percentage of equity that they can select diminishes as they age. When employees reach retirement, their savings are converted into annuities. The government auctions off the rights to annuitize retirees in groups of 250,000.

This brilliantly conceived approach solves thorny behavioral and institutional challenges. Behaviorally, it recognizes that people are not good at two aspects of financial planning for retirement—deciding to save and eliminating risk in later years—and it forces them to act in a better way. At the same time, the system acknowledges that people who enroll in retirement plans are reasonably good at managing their own risk. So investment choices are left to the individual, with limits on too-risky behavior, especially as a person ages, when bad choices can do irrecoverable damage.

Institutionally, Chile has cracked an age-old problem with annuities. It’s risky business to predict how long people will live, so insurance companies charge a high premium to cover that risk, which makes for an inefficient market. Annuities also suffer from an adverse selection problem, further increasing risk. (The classic example of adverse selection is health insurance: The healthiest people are the least likely to opt in, which increases the pool’s riskiness, making health care less appealing for insurance companies and policies more expensive for the people who want them.) By pooling the risk, the Chilean government makes annuities an attractive business with more competition and better prices. And since everyone is forced to annuitize, the adverse selection problem simply disappears.

I was impressed with this system and wondered how it would fly in the United States, where our own mandated savings program—Social Security—undergoes sporadic efforts to privatize it.

I suspect Americans would consider the Chilean system heavy-handed and limiting—a flagrant example of nanny-state control. You can force me to save money when you pry it from my cold, dead hands. Paradoxically, we happily accept deeply controlling (and expensive) regulation on our behavior in other areas with little thought or protest. Consider the strictures we allow on driving. Wear a seat belt. Drive this speed. Bear the cost of air bags. Pollute only this much. Don’t text while driving.

Why do we accept so much government intervention in driving but chafe when it comes to a few simple rules that would help us make better financial decisions? It’s probably not because we think we’re smarter about finances than driving. I think the reason has to do with our ability to imagine negative consequences. Car wrecks have a way of vividly communicating our incompetence as drivers and making the benefits of regulation crystal clear. Poor money management can carry similarly devastating consequences, but they are less readily apparent. Even in times of economic crisis, we don’t recognize our own bad judgment because people around us are in the same boat and we compare our fortune with theirs.

But the inability to see our own irrationality shouldn’t be an excuse to let it go unchecked. We need to analyze what people and markets are good at and what they’re not good at, and use those insights to improve our institutions. Chile’s approach to saving shows us that it can be done, and done well.

When going on a first date, we try to achieve a delicate balance between expressing ourselves, learning about the other person, but also not offending anyone — favoring friendly over controversial – even at the risk of sounding dull. This approach might be best exemplified by an amusing quote from the film Best in Show: “We have so much in common, we both love soup and snow peas, we love the outdoors, and talking and not talking. We could not talk or talk forever and still find things to not talk about.” Basically, in an attempt to coordinate on the right dating strategy, we stick to universally shared interests like food or the weather. It’s easy to talk about our views on mushroom and anchovies, and the topic arises easily over dinner at a pizzeria – still, that doesn’t guarantee a stimulating conversation, and certainly not a real measure of our long-term romantic match.

This is what economists call a bad equilibrium – it is a strategy that all the players in the game can adopt and converge on – but it is not a desirable outcome for anyone.

We decided to look at this problem in the context of online dating. We picked apart emails sent between online daters, prepared to dissect the juicy details of first introductions. And we found a general trend supporting the idea that people like to maintain boring equilibrium at all costs: we found a lot of people who may, in actuality, have interesting things to say, but presented themselves as utterly insipid in their written conversations. The dialogue was boring, consisting mainly of questions like, “Where did you go to college?” or “What are your hobbies?” “What is your line of work?” etc.

We sensed a compulsion to avoid rocking the boat, and so we decided to push these hesitant daters overboard. What did we do? We limited the type of discussions that online daters could engage in by eliminating their ability to ask anything that they wanted and giving them a preset list of questions and allowing them to ask only these questions. The questions we chose had nothing to do with the weather and how many brothers and sisters they have, and instead all the questions were interesting and personally revealing (ie., “how many romantic partners did you have?”, “When was your last breakup?”, “Do you have any STDs?”, “Have you ever broken someone’s heart?”, “How do you feel about abortion?”). Our daters had to choose questions from the list to ask another dater, and could not ask anything else. They were forced to risk it by posing questions that are considered outside of generally accepted bounds. And their partners responded, creating much livelier conversations than we had seen when daters came up with their own questions. Instead of talking about the World Cup or their favorite desserts, they shared their innermost fears or told the story of losing their virginity. Everyone, both sender and replier, was happier with the interaction.

What we learned from this little experiment is that when people are free to choose what type of discussions they want to have, they often gravitate toward an equilibrium that is easy to maintain but one that no one really enjoys or benefits from. The good news is that if we restrict the equilibria we can get people to gravitate toward behaviors that are better for everyone (more generally this suggests that some restricted marketplaces can yield more desirable outcomes).

And what can you do personally with this idea? Think about what you can do to make sure that your discussions are not the boring but not risky type. Maybe set the rules of discussion upfront and get your partner to agree that tonight you will only ask questions and talk about things you are truly interested in. Maybe you can agree to ask 5 difficult questions first, instead of wasting time talking about your favorite colors. Or maybe we can create a list of topics that are not allowed. By forcing people to step out of their comfort zone, risk tipping the relationship equilibria, we might ultimately gain more.

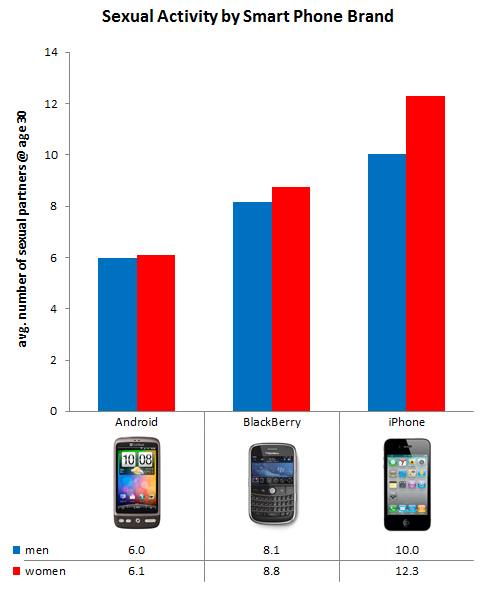

Popular online dating site OkCupid recently released some numbers users reported regarding their sex lives. One interesting correlation was between smart phone usage and number of sexual partners. As you see below, women iPhone users (at the age of 30) report having had 12.3 sexual partners, over twice as many as women Android users. Male smart phone users show a similar jump: from 6.0 sexual partners on Android to 10 on the iPhone. Blackberry users fall almost exactly in the middle.

The conclusion seems very simple: Look for a cute iPhone owner to get lucky with.

But, being careful about interpreting correlational data (and an avid iPhone user, I might add), I’ll offer a bit of advice: Please consider an alternative explanation of this graph: that iPhone owners might simply be more prone to exaggerate…..

One of the most general principles of human decision making is that we use relativity as a way to figure out how much we value things. We see a sale sign and the comparison of the current price to a more expensive past price makes us think that we are standing in front of a good deal. We see a modestly prices sweater next to a much more expensive one and we reason that is it a better deal for the money. And so on.

Relativity is not always the right strategy for figuring out how much to value things (very often it is not), but it gives us a quick and handy tool for going about the world making decisions.

Over the years the same type of relative decision making has been shown in monkeys, birds, and bees, but now it has been shown even with very simple lifeforms — the slime mould, Physarum polycephalum

Latty and Beekman did one such test using two food sources – one containing 3% oatmeal and covered in darkness (known as 3D), and another with 5% oatmeal that was brightly lit (5L). Bright light easily damages the slime mould, so it had to choose between a heftier but more irritating food source, and a smaller but more pleasant one. With no clear winner, it’s not surprising that the slime mould had no preference – it oozed towards each option just as often as the other.

But things changed when the researchers added a third option into the mix – a food source containing 1% oatmeal and shrouded in shadow (1D). This third alternative is clearly the inferior one, and the slime mould had little time for it. However, its presence changed the mould’s attitude toward the previous two options. Now, 80% of the slime mould headed towards the 3D source, while around 20% chose the brightly-lit 5L one. Even for slime mould relativity matters, suggesting that it is a very basic form of decision making!

The Magic of Procrastination

Oscar Wilde once said, “I never put off till tomorrow what I can do the day after.” As a university professor, I constantly see Wilde’s words put into action. Each fall students arrive to the first day of class determined to meet deadlines and stay on top of their assignments. And each fall the human weakness to procrastinate gets the best of them. After a few years of witnessing this behavior, my colleague Klaus Wertenbroch and I worked up a few studies hoping to get to the root of this problem. Our guinea pigs were the delightful students in my class on consumer behavior.

As they settled into their chairs that first morning, I explained to them that they would have to submit three main papers over the 12-week semester and that these three papers would constitute a large part of their final grade. “And what are the deadlines?” asked one student. I smiled. “The deadlines are entirely up to you and you can hand in the papers any time before the end of the semester,” I replied. “But, by the end of this week, you must commit to a deadline for each paper. Once you set your deadlines, they can’t be changed. Late papers,” I added, “would be penalized at the rate of one percent off the grade for each day late.”

“But Professor Ariely,” asked another student, “given these instructions wouldn’t it make sense for us to select the last date possible?” “That’s an option,” I replied. “If you find that it makes sense, by all means do it.”

Now a perfectly rational student would set all the deadlines for the last day of class—after all, they could submit papers early, so why take a chance and select an earlier deadline than absolutely necessary? From this perspective, delaying the deadlines to the last day of he semester was clearly the best decision. But what if the students succumbed to temptation and procrastination? What if they knew that they are likely to fail? If the students were not rational and knew it, then they might set early deadlines and by doing so force themselves to start working on the projects earlier in the semester.

You would most likely predict that the students would succumb to procrastination (not a big surprise there)—but would they understand their own limitations and would they commit to earlier deadlines just to overcome their procrastination?

Interestingly, we found that the majority of students committed to earlier deadlines, and that this ability to commit resulted in higher grades. More generally, it seems that simply offering students a tool by which they could pre-commit publically to deadlines can help them achieve their goals.

How does this finding apply to non-students? When resolving to reach a goal—whether it is tackling a big project at work or saving for a vacation, it might help to first commit to a hard and clear deadline, and then inform our colleagues, friends, or spouse about it with the hope that this clear and public commitment will help keep us on track and ultimately fulfill our resolutions.

The dark side of “Productivity Enhancing Tools”

Email, Facebook, and Twitter have greatly enhanced the ways we communicate. These handy modes of communication allow us to stay in touch with people all over the world without the restrictions of snail mail (too slow) or the telephone (is it too late/early to call?). As great as these communication tools are, they can also be major time-sinks. And even those of us who recognize their inefficiencies still fall into their trap. Why is this?

I think it has something to do with what the behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner called “schedules of reinforcement.” Skinner used this phrase to describe the relationship between actions (in his case, a hungry rat pressing a lever in a so-called Skinner box) and their associated rewards (pellets of food). In particular, Skinner distinguished between fixed-ratio schedules of reinforcement and variable-ratio schedules of reinforcement. Under a fixed schedule, a rat received a reward of food after it pressed the lever a fixed number of times—say 100 times. Under the variable schedule, the rat earned the food pellet after it pressed the lever a random number of times. Sometimes it would receive the food after pressing 10 times, and sometimes after pressing 200 times.

Thus, under the variable schedule of reinforcement, the arrival of the reward is unpredictable. On the face of it, one might expect that the fixed schedules of reinforcement would be more motivating and rewarding because the rat can learn to predict the outcome of his work. Instead, Skinner found that the variable schedules were actually more motivating. The most telling result was that when the rewards ceased, the rats that were under the fixed schedules stopped working almost immediately, but those under the variable schedules kept working for a very long time.

So, what do food pellets have to do with e-mail? If you think about it, e-mail is very much like trying to get the pellet rewards. Most of it is junk and the equivalent to pulling the lever and getting nothing in return, but every so often we receive a message that we really want. Maybe it contains good news about a job, a bit of gossip, a note from someone we haven’t heard from in a long time, or some important piece of information. We are so happy to receive the unexpected e-mail (pellet) that we become addicted to checking, hoping for more such surprises. We just keep pressing that lever, over and over again, until we get our reward.

This explanation gives me a better understanding of my own e-mail addiction, and more important, it might suggest a few means of escape from this Skinner box and its variable schedule of reinforcement. One helpful approach I’ve discovered is to turn off the automatic e-mail-checking feature. This action doesn’t eliminate my checking email too often, but it reduces the frequency with which my computer notifies me that I have new e-mail waiting (some of it, I would think to myself, must be interesting, urgent, or relevant). Another way I am trying to wean myself from continuously checking email (a tendency that only got worse for me when I got an iPhone), is by only checking email during specific blocks of time. If we understand the hold that a random schedule of reinforcement has on our email behavior, maybe, just maybe we can outsmart our own nature.

Even Skinner had a trick to counterbalance daily distractions: As soon as he arrived at his office, he would write 800 words on whatever research project he happened to be working on—and he did this before doing anything else. Granted, 800 words is not a lot in the scheme of things but if you think about writing 800 words each day you would realize how this small output can add up over time. I am also quite certain that if Skinner had email he would similarly not have checked it before putting in a few hours of productive work. Now if we could only learn something from one of the world’s experts on learning….

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like