The Facebook IPO: A Note to Mark Zuckerberg; or, With “Friends” Like Morgan Stanley, Who Needs Enemies?

I just received this letter from a friend in the banking industry. He prefers to remain anonymous (you’ll see why soon enough).

Dear Mark,

There’s been a lot of ballyhoo recently about your IPO and your choice of investment bankers. Indeed, a war was fought by the banks to win your “deal of the decade.” As reported in the press, the competition was so intense banks slashed their fees in order to win your business. Facebook is “only” paying a 1% “commission” for its IPO rather than the 3% typically charged by the banks.

Congratulations, Mr. Zuckerberg! On the surface it appears your pals in investment banking have given you a quite a deal!… Or have they?

Let’s take a closer look and see what you’re getting for your money.

To start, your bankers have the task of selling 388 million Facebook shares to the public. In return, these banks will receive $150 million for their efforts. Morgan Stanley will get the largest share of that amount—approximately $45 million. But is $45 million all that Morgan Stanley makes off your deal?

Before we answer this question, let’s first dissect the sales pitch that Morgan Stanley probably gave you to justify “only” the $150 million fee. We’ll look at what they told you, and then what that actually means.

1) We will raise the optimal amount of money for the company, for our 1% fee. (Translation: How great is it that Zuckerberg believes he got a great deal by getting us down to a 1% fee! We can’t believe he got hoodwinked into agreeing to any level of what are actually variable commission fees.)

2) The definition of a successful deal is having a good price “pop” on the first day of trading. This will make all parties happy and you, Mark, look like a rock star. (Translation: No one benefits more than us if Facebook’s share price rises significantly on day one. That first day price “pop” will take money directly out of your pocket and puts it in ours and those of our “best friends”—not yours or the public stockholders. We will, at almost all costs, make this happen.)

3) This is a very complicated process, especially for such a large company, but we are here to successfully guide you through it. (Translation: It actually takes the same amount of work to do a large IPO as a small one. Thus for approximately the same amount of work we’re doing for Facebook, we sometimes get only $10 million—$140 million less than we’re making on Zuckerberg’s IPO.)

4) We will perform due diligence on your company to make sure the business and its finances are as they seem. (Translation: While it certainly does take some time and effort to perform reasonable due diligence, Facebook is a very large and well-known company, and we have done this same procedure hundreds of times.)

5) We will write a prospectus that outlines Facebook’s strategy, business plan, financials, and risks, and we will get it approved by the SEC. (Translation: Per the regulatory guidelines, a prospectus is largely a boilerplate document; for the most part, it’s just a lot of cutting and pasting.)

6) Once this prospectus is completed and with input from the Facebook team, we will come up with “the range” or the approximate price we think your IPO shares should be sold at to the fund managers. (Translation: The price of your IPO will be determined by where and how we can best optimize our (secret) profits on the deal.)

7) We believe the best shareholders are large fund managers, as they will become long-term holders of Facebook stock. However, at your request, we will allocate 25% of the IPO shares to sell to individual investors. (Translation: There are 835 million Facebook users worldwide. One could argue that what is best for Facebook would be to let all of Facebook’s legally eligible customers enter orders to buy Facebook stock. Then through the broker of their choosing, they could enter the quantity of shares they want to buy and the price they want to pay, just like the fund managers do—or are supposed to do. More on this scenario below.)

8) Our 10-day sales process will begin. For this important “road show,” you will be introduced to our large fund manager clients. These fund managers will receive our pitch for why they should buy your stock, and we will assess their interest and at what price. (Translation: Far from being long-term holders, many of our large fund manager “best friends” will, as soon as Facebook shares start trading, sell (or “flip”) for a windfall profit on all the underpriced shares we’ve given them. We’ll enable this by creating a perceived “feeding frenzy” for the stock by putting out an artificially low initial estimate ($28 to $35 per share) for where we think the IPO will be priced. We will then raise that estimate during the road show. Rumors about this begin to circulate over the next day or so.)

9) At the end of the road show on the night before the IPO, we will review the overall supply and demand for the stock and then “price” the shares. This is the price at which the large fund managers will receive their “winning” Facebook shares. (Translation: The price of the stock is already known. For the past few years, Facebook shares have been actively trading on such venues as SecondMarket and SharePost.)

10) And finally, we will put a mechanism, called a Greenshoe, in place that “supports” your share price after the IPO. (Translation: Thank God Zuckerberg doesn’t understand one of the greatest investment banking profit enhancing creations of all time—“The Greenshoe.” The Greenshoe will likely be our most profitable part of this deal. It’s a secret windfall, and although we market it to Facebook as a method to stabilize its share price, it’s really just another way for us, with little effort, to make huge amounts of money.)

We’re not done yet, Mark. Now, I’d like to dig a bit deeper into what’s going to happen and show you all the additional ways your banker friends and their large fund manager clients are going to make oodles of money off your deal.

1) Morgan Stanley only gives Facebook shares (“golden tickets”) to their best client “friends.” In other words, it’s no coincidence that Morgan Stanley’s biggest fund manager clients get the bulk of the shares offered in this kind of deal.

2) How do you become best friends with Morgan Stanley? There are lots of ways, such as trading tens of millions of shares with them or using the firm as your prime broker.

3) I’m sure there are a lot of conversations going on right now between Morgan Stanley’s salespeople and their clients. These conversations are probably along the lines of (wink-wink) “before we allocate our Facebook shares, we’d like to ask first if you plan to do more trading with us over the next week to six months….”

4) Let’s assume that 50 of Morgan Stanley’s “best friends” trade an extra 2 million shares so they can get access to more shares of the Facebook IPO. Let’s also assume that the average commission these clients pay to Morgan Stanley is 2 cents per share. Well, those extra trades will dump an additional $2 million dollars into Morgan’s coffers.

5) Now comes the part where Morgan Stanley actually gives free money to its friends. If the Facebook IPO is like the majority of other recent Internet offerings, here’s what Morgan Stanley will likely do. They know Facebook will be a “hot” deal. Especially, with all of the “5% orders” coming in, there will be huge demand for Facebook shares. My prediction is that Morgan Stanley will “price” Facebook at approximately $40 per share. This is the price at which Morgan Stanley’s “best friends will be able to buy the bulk of the 388 million shares offered.

6) Now let’s now assume that Facebook shares open for trading at $50—a lower percentage premium than Groupon’s opening share-price “pop.”

7) Let’s assume that one of Morgan Stanley’s “best friends” decides to sell 3 million shares right after the opening at $50 per share. That “best friend” will instantaneously make a $30 million profit. That’s right, a $30 million profit.

8) Here’s a question for you Mark. If Morgan Stanley’s “best friends” are selling Facebook shares at $50, who’s buying them? The answer is your “friends,” individual investors, most of whom are your customers.

9) Now for the final insult—the Greenshoe. Technically speaking, the Greenshoe gives your investment banks a 30-day option to purchase up to 15% more stock from Facebook than was registered and sold in the IPO. In layman’s terms, this means that, over the next 30 days, your “best friends” at the investment banks are able to buy approximately 50 million of your shares at $40 per share.

10) As in our example above, let’s say Facebook shares do trade at $50 soon after the IPO. Now I am a simple person, but if I were given the opportunity to buy something at $40 that I could immediately sell at $50, I would do it all day, every day…. And so will the investment banks. The Greenshoe actually gives these banks the ability to do this for 50 million of your shares.

11) So let’s assume that Morgan Stanley and its other banking “friends” buy 50 million shares at $40 per share and then sell these shares at $50. Morgan Stanley and its banking “friends” will make an additional $500 million- yes, $500 million- a HALF BILLION DOLLARS off your company.

So let’s now do a tally to see how much money all of your banking friends are going to make just for the privilege of doing your IPO. Let’s also see where this money comes from.

“Discounted” fees/commission: $150 million

Greenshoe profits: about $500 million

Extra trading commissions from large fund managers: approximately $10 million

—————

Investment Bank Profits: $660 million

As the lead bank on your deal, Morgan Stanley is likely to get 30% of the overall take. This means that your closest investment banking “friend” will make a bit more than $200 million from your IPO.

Morgan Stanley and the rest of the investment banks involved will also make sure that their favorite fund manager client “friends” are given lots of free money. Assuming that these “friends” are given 75% of the total number of IPO shares, or a total of 291 million shares, and assuming that the stock does rise from $40 to $50, then these fund managers will collectively, in one day, make $2.9 billion dollars in realized or unrealized profits. That’s right, 2.9 BILLION DOLLARS.

Mark, by now you must be asking yourself the obvious question. “Where and out of whose pocket does this money come from?”

Well, just think of it this way… Let’s assume you own a very expensive piece of waterfront real estate, and you hire a broker to sell it for you. After exploring the market and after getting indications of interest, your broker advises you that $10 million would be a great price for your home. You meet with the potential buyers and decide to sell it for $10 million. After the $1 million commission you have to pay your broker, your net proceeds are $9 million. An hour later, you drive by the house and see your broker in the driveway shaking hands with some different people. You pull over to see what’s going on, and you find that the people you just sold the house to for $10 million are very close friends of your broker. To your dismay, you also find out that those friends just sold your (former) house to somebody else for $15 million.

The same exact game is going on here, Mark. You’ll be selling 388 million shares of Facebook stock in your IPO. A likely scenario is that your broker “friends” are telling you to sell your shares at $40 per share. You’ll take their advice and sell at $40 per share, and the buyers will be Morgan Stanley’s biggest fund management clients. By the time you drive around the block, these folks will have sold their shares at $50 per share. In other words, using the same real estate scenario, you’ll have sold something of yours for $15 billion that is really worth $19 billion. And for that “unique” privilege, you’ll be paying your “friends” at the banks $150 million as a fee.

Makes you wonder who your real friends are…

————-

End of letter

————-

I find the points that my (real life) friend makes here highly disturbing, but I suspect that they also fit with what we now know about dishonesty.

First, although there are many ethically questionable practices occurring here, it’s not clear that anything illegal is going on. Second, I think that while this banking industry’s IPO process is artfully designed in such a way that, although overall it’s good for the bankers and less so for the companies, no single individual believes he/she is doing anything wrong. Third, I also suspect that since this is such a common practice, the bankers most likely truly believe that mechanisms such as getting a first-day IPO “pop” is great for Facebook and that the Greenshoe is fact put in place to stabilize the Facebook stock price, and not simply to generate more windfall profits for themselves. Forth, they probably believe in their own definition of a “successful” IPO, which in their terms is one where the stock is priced at $40 and quickly trades up to $50. In the case of Facebook, this process simply redistributes $4 billion from Facebook to the banks and the large fund managers. For Zuckerberg and his team, I have to wonder whether the emotional value of a first day share price “pop” is worth $4 billion.

I am not sure about you, but I find all of this very depressing.

Irrationally yours,

Dan

It’s not a lie if…

It’s not a lie if…”

Based on George Costanza’s advice to Jerry Seinfeld:

THE LIST

1. It’s not a lie if you believe it.

2. It’s not a lie if it doesn’t help you.

3. It’s not a lie if it hurts you.

4. It’s not a lie if it helps someone else.

5. It’s not a lie if it doesn’t hurt someone else.

6. It’s not a lie if everyone expects you to lie.

7. It’s not a lie if the other person knows the truth.

8. It’s not a lie if nobody can prove it.

9. It’s not a lie if you don’t get caught.

10. It’s not a lie if you don’t need to tell another lie to cover it up.

11. It’s not a lie if you were crossing your fingers.

12. It’s not a lie if you proceed to make it true.

13. It’s not a lie if nobody heard you say it.

14. It’s not a lie if nobody cares.

Irrationally yours

Dan

Turning the Tables: FDR, Tom Sawyer, and me

Before television and the internet, political candidates had two primary means of getting their image out into the public: live appearances and campaign posters. And given the limited reach of the former, posters were a crucial element in political strategy. How else were candidates supposed to project an image of decisiveness and gravitas?

So when Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for governor of New York in 1928, his campaign manager had thousands of posters printed with Roosevelt looking at the viewer with serene confidence. There was just one problem. The campaign manager realized they didn’t have the rights to the photo from the small studio where it had been taken.

Using the posters could have gotten the campaign sued, which would have meant bad publicity and monetary loss. Not using the posters would have guaranteed equally bad results—no publicity and monetary loss. The race was extremely close, so what was he to do? He decided to reframe the issue. He called the owner of the studio (and the photograph) and told him that Roosevelt’s campaign was choosing a portrait from those taken by a number of fledgling artists and studios. “How much would you be willing to pay to see your work hung up all over New York?” he asked the owner. The owner thought for a minute and responded that he would be willing to pay $120 for the privilege of providing Roosevelt’s photo. He happily informed him that he accepted the offer and gave him the address to which he could send the check. With this small rearrangement of the facts, the crafty campaign manager was able to turn lose-lose into win-win.

This story reminds me of the famed trickster, Tom Sawyer, who duped the neighborhood boys into trading him toys and apples for the chance to whitewash a fence. When one of the boys taunted him for having to work instead of going swimming, Tom responded with all seriousness, “I don’t see why I oughtn’t to like it. Does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?” Then when the boy asked for a chance to try it, Tom hemmed and hawed until finally the boy said he would give up his apple for a chance to whitewash the fence. Once Tom had one taker, outsourcing the rest of the work to other boys was a snap.

I conducted a similar experiment in a class I was teaching on managerial psychology. One day, I opened my lecture with a brief reading of a poem by Walt Whitman, after which I informed the students I would be doing a few short poetry readings, and that space was limited. I passed out sheets of paper providing students with the schedule of these readings along with a survey. Half of the students were asked whether they would be willing to pay $10 to come listen to my reading; the other half were asked whether they would be willing to listen to my reading in exchange for $10. Sure enough, those in the second group set a price for enduring my poetry reading (ranging from $1 to $5). The first half, however, seemed quite willing to pay to attend my poetry reading (from $1 to about $4). Keep in mind that the second group could have turned the tables and asked to be paid for listening to my recitation, but they didn’t.

In all of these situations, people (the campaign manager, Sawyer, and myself) were able to take a situation of disadvantage or ambiguous value and spin it to their (my) advantage. Once Sawyer pretended to be unwilling to part with the privilege of whitewashing, other boys wanted it, because obviously Tom was hoarding all the fun. When I told my students that space was limited and gave a suggested price for the recitation, I created the idea that this was an experience they would definitely want to have (as opposed to the other group, to whom I insinuated that listening to my reading of Whitman might be less than enjoyable).

I think Twain summed this strategy up best when he wrote the following about Tom: “He had discovered a great law of human action, without knowing it – namely, that in order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain.”

Taxes and Cheating

Will Rogers once said that “The income tax has made liars out of more Americans than golf” and I worry that he was correct. During his confirmation hearing to become the Treasury Secretary, it was revealed that Tim Geithner failed to pay Medicare, Social Security, and payroll taxes for several years while he worked for the International Monetary Fund (IMF). When asked by Senator John Kyl (R AZ) during the hearing about the (more than $40,000) “mistake,” which Geithner blamed on the tax software he was using, he replied, “it was very clear that this was an avoidable mistake… You’re right. I had many opportunities to see it.” But he didn’t, apparently, and that was that.

There are many problems here—one of which is the possibility of a double standard that allowed Geithner to get away with this entirely (I am not sure if this is the case or not). I suspect that if he had he been working for a domestic monetary agency, that is, the IRS, he would have faced heavy prosecution, fines, and almost certainly been fired. Also, as the future head of the Treasury, we might hope that he understands the tax code well enough to do his own taxes. Part of his defense, was, of course, that the code is too complex. Which is true, but in light of this, and his own errors, we might then hope he would be more aggressive about reforming the code, which he has not. The worst part of it, however, is the personal example he provided to the rest of the American taxpayers: do your taxes wrong, omit a few things, and if they catch you all you need is to pay it back — it’s basically okay.

I’m not calling for punishing Geithner (retribution isn’t necessarily helpful, not to mention it’s a little late), but as we draw closer to tax time, it’s worth recalling this incident and how it might affect the American public. In the research my colleagues and I have carried out on dishonesty, we’ve found repeatedly that people become more likely to lie and cheat after witnessing the dishonest behavior of others. In one of our experiments, we tested to see how participants would respond to a blatant act of dishonesty in their midst—would they think they too could cheat and get away with it, or would they perhaps straighten up and fly righter than ever? To find out, we gave participants 5 minutes to solve as many mathematical problems as possible (where they were instructed to find which two numbers out of 12 add up to 10).

In the control, where no cheating was allowed, the average student solved 7 problems, which gave them a pay off of $3.50 out of a maximum of $10 (if they solved all 20 problems). To see how witnessing and act of dishonesty would affect participants, we had one student—a confederate named David—stand up after only a minute and claim he’d solved all 20 matrices. The experimenter merely responded that in that case he could take his earnings and go. So how did the participants respond to this display when asked to self-report the number of matrices they solved? By cheating a whole lot: they claimed an average of 15 correct answers, more than twice the average score when cheating was not allowed.

Seeing someone cheat for their own benefit and then get away with it clearly has an impact on our moral behavior—loosening it to a substantial degree.

So, what does this experiment means for paying taxes? It means that the more we see politicians—the people who make our laws—fudge their taxes (which seems to happen continually), the more likely the rest of us are to adjust our understanding of what is right and wrong about paying our taxes, and do the same.

But there is hope. When we ran the same experiment with one slight difference, we found that dishonesty decreased dramatically. This time, instead of looking like all the other participants, who were students at Carnegie Mellon University, we had our confederate wear a sweatshirt that located him within a different social group. This time h was wearing a University of Pittsburgh sweatshirt (Carnegie Mellon’s neighboring and rival university). When the dishonest act was committed by a person from an out-group, we found that cheating decreased dramatically to the lowest level in all the experiments (participants claimed “only” 9 correct problems).

What this means is that if we think of ourselves and our politicians as being part of the same social group, we might follow their footsteps when we hear about another politician or celebrity who hasn’t paid taxes in years. On the other hand, if we don’t think that we belong to the same social group we might not feel more justified in our own moral indiscretions, and instead be extra careful not to be confused with this other, not so moral, social group.

So the moral of the story is: when you settle in to work on your taxes in the next few weeks, try not to think about the individuals who cheat on their taxes—and if you can’t avoid thinking about them, at least try to separate your own social group from theirs.

Go forth and be financially virtuous.

Dan Ariely is the James B Duke professor of Psychology and behavioral Economics at Duke University and the author of (the soon to be released) The Honest Truth About Dishonesty.

TSA: Wasteful and Insecure

I travel a great deal so I frequently find myself in the company of TSA agents who check my boarding pass, remind me to remove my shoes, jacket, belt, laptop, liquids, and all items from my pockets (including the previously inspected boarding pass), and then screen these things, as well as myself. Every time I find myself standing in line, in my socks, I inevitably contemplate the efficiency of the system. It’s only half an hour or so per flight, but when you multiply that number by all the people traveling in the United States, it’s a tremendous amount of time, effort, and money. And this comes not only from the TSA, but also in the form of lost productivity of all the people standing in line in various states of undress. One has to wonder whether it’s worth it.

It’s likely that on an individual level, we’re merely annoyed by the time and hassle of the present security routine, after all, it’s difficult to imagine how many resources are being used as you hurry through the lines. Lucky for us, this organization made a fantastic flowchart to help us see how much time and money we’re spending collectively on TSA, and, more importantly, what kind of results that investment is yielding. Judging from the price (over $60 billion) versus results (very few that are discernable), the question is: what do we do? Clearly we want to be safe and we want to prevent any terrorist activities, but it doesn’t seem that the current system is working, to say nothing of efficiency.

Perhaps in this situation, more is less. That is, maybe if we’re willing to give up more information about our travels and our lives, we’ll have to endure less time-consuming and haphazard scrutiny at the airport. For example, I recently had an interview with U.S. Customs and Border Protection as part of the Global Online Enrollment System (GOES), which preauthorizes approved frequent travelers to enter the US more quickly. I allowed them to do a background and credit check, and then met with an officer for an interview so that he could determine whether I posed any security risks (I’m happy to say I do not). Essentially, I opted for a reduction in privacy in return for not spending half an hour several times a week in line. For now it only applies to in-bound international flights, but I hope it will become more widespread.

At bottom, we have to give up some freedom and information in exchange for security. There’s no avoiding it. So the question is whether we want to do that in half-hour, invasive (not to mention ineffective) increments, or to go through a longer process once that looks further into our lives. Because the cost of the former comes is in small, redundant bits, we tend to overlook it, but in terms of hassle and time spent collectively, the second is a far better option.

That said, similar approaches to cutting time and money spent on security checks for domestic travel might be worthwhile. If individuals could agree to being tracked to a higher degree in order to gain quicker passage through security lines, it would allow TSA (or perhaps another group in charge of security) to know more readily who is and is not on flights. That way we could stop the inanity of having to take off our shoes, being x-rayed, and limiting liquids to theoretically non-explosive amounts.

After all, when you consider the approach to security so far, who knows what the next step might be—will we have to wear certain clothes only, carry only certain kinds of luggage, or no luggage at all? Instead we need a comprehensive approach that addresses concerns more fully, rather than the reactionary, piecemeal approach we have at present.

Honest Tea Declares Chicago Most Honest City, New York Least Honest

From the Huffington Post:

Would you still pay a dollar for Honest Tea if you could take it for free? On July 19, the company conducted an Honest Cities social experiment—it placed unmanned beverage kiosks in 12 American cities. There was a box for people to slip a dollar in, but there were no consequences if they did not pay.

Turns out, Americans (or at least Americans who like Honest Tea) are pretty gosh darn honest. Chicago was the most honest city, with 99 percent of people still paying a dollar. New York was the least honest city—only 86 percent coughed up the buck.

The full results:

Chicago: 99%

Boston: 97%

Seattle: 97%

Dallas: 97%

Atlanta: 96%

Philadelphia: 96%

Cincinnati: 95%

San Francisco: 93%

Miami: 92%

Washington, DC: 91%

Los Angeles: 88%

New York: 86%Honest Tea is donating all of the money collected, nearly $5,000, to Share Our Strength, City Year and Rails-to-Trails Conservancy. The company is matching the total, bringing the total donated to $10,000.

What kinds of things might have changed this very honest behavior?

Here are some open questions, or maybe future experiments to try:

1) What if the box for paying was not transparent? If it was opaque, then no one could see if the person in front of the box was really paying and there was no evidence that many people have paid before (based on the number of dollars that were there)

2) What if people approached the booth one by one and without being observed by anyone?

3) What if the experiment was conducted at night? What if people were slightly drunk?

4) What if there was an actor who would go by and take a bottle without paying? Would it make the other people be less honest? (I think so)

5) Who is more likely to be dishonest, people who come as individuals, or people who come in groups?

6) When it is sunny and people are happier, are they also more honest?

What is clear is that there are lots of interesting questions here.

The Behavioral Economics of Eating Animals

Throughout my life, I have loved eating meat, but my two best friends at Duke are vegetarians, and because of them I was persuaded to read Eating Animals by one of my favorite contemporary authors, Jonathan Safran Foer. While Foer mainly writes novels, his newest book is non-fiction, and discusses many topics that revolve around, well…eating animals.

One of the main takeaways from the book is that the vast majority (about 99%) of the meat we eat in America comes from factory farms, where animals face a shocking level of unnecessary suffering, a kind of suffering that is generally unseen at local, organic farms. After reading the book, I still eat meat, but only if it comes from humanely-raised sources.

While reading Eating Animals, I couldn’t help but think of behavioral economics (a topic which, admittedly, is often on my mind anyway), and how so many behavioral economic principles seem to apply to various patterns of people’s general thoughts, emotions, and actions regarding meat. While I do not have the empirical data to support my musings, I figured I would share them as “food for thought.”

Identifiable Victim Effect: The massive scale on which factory farms operate is precisely what makes it so difficult to sympathize with the animals within them.

- Animal Abuse: Many people would be horrified if they saw a dog being hit by its owner, yet are relatively unconcerned (or just don’t think about) that the piece of meat they are eating undoubtedly lived a life of incomparably greater pain.

- Hunting: Many find hunting immoral, yet animals that are hunted would generally have lived a much better life up until death than animals in factory farms (e.g., the Sarah Palin hunting controversy and Aaron Sorkin’s infamous letter criticizing her, even though he is not a vegetarian, and so presumably eats factory-farmed meat..

One Step Removed (see the “Coke vs. dollar” study): Many would find it immoral to treat a cow, pig, or chicken the way that the ones we eventually eat are, but aren’t fazed with it being done for us indirectly by others (or just don’t think about it either way).

Social Norms and “Us” vs. “Them” (see the CMU vs. UPitt cheating study): Many non-vegetarians see others eating meat indiscriminately and so think doing so is OK, and may not stop and think much about a vegetarian’s reasons for not eating meat (which may be reasons non-vegetarians would actually agree with, too) because vegetarians may automatically be categorized as a fringe group.

“Hot” vs. “Cold” States (see the “laptop” study): Our food decisions (and therefore, our thinking about food) often occur when we are already in the “hot” state of hunger. When we are not hungry at all (in a “cold” state), we are probably more receptive to the logical arguments against eating factory-farmed meat, and might agree to do so. But the hungrier we get, the more likely we are to do something we might think of as unethical. This is the same reason that people find it so easy to find the resolve to quit smoking just after a cigarette, but nearly impossible when cravings set back in.

Paradox of Choice: Limiting our food options (by cutting out factory-farmed food options) should help us better appreciate the options that remain for us.

Dating: I was told that many vegetarians will only date fellow vegetarians, and the majority of vegetarians are female (60-67%)…so the demand for potential vegetarian males is much greater than the supply. Thus, for males, it would be irrational not to be a vegetarian to allow yourself access to this wonderful market of potential dates.

~Jared Wolfe~

Dishonest Drunks

When you think about behavioral science research, the image that probably comes to mind is that of laboratories, computers, surveys, electrodes, and maybe even rats — but you may not realize the amount of research conducted in the field. At the Center for Advanced Hindsight we certainly do our share of lab research, but we also like to shake things up and occasionally target the unsuspecting participant in their favorite local setting. For instance, you might find us at a popular eatery, your favorite independent bookstore, a busy shopping center, a science fair, or even driving around in our fancy research mobile.

When you think about behavioral science research, the image that probably comes to mind is that of laboratories, computers, surveys, electrodes, and maybe even rats — but you may not realize the amount of research conducted in the field. At the Center for Advanced Hindsight we certainly do our share of lab research, but we also like to shake things up and occasionally target the unsuspecting participant in their favorite local setting. For instance, you might find us at a popular eatery, your favorite independent bookstore, a busy shopping center, a science fair, or even driving around in our fancy research mobile.

On one of our latest excursions, we ventured out to Franklin Street, a hot spot for many Chapel Hillians to have a drink (or a few) and a good time. When the night was upon us we set out to answer the question: are you more likely to cheat when you’re drunk?

So we set up two research stations and waited for the bar crawlers to crawl. As the night progressed we surveyed the bar, recruiting bar-goers of varying drunkenness. Participants, many with drink in hand, played a 15-minute computer game that was designed to test their honesty. The game was a simple task where participants chose to pay themselves more or less money based on their choices in the game, and of course some of their decisions turned out to be more honest than others. We visited a wide array of bar scenes from the local band crowd to the underground pool players, the 90’s hip hoppers, the indie rockers, and even the Carrborites — and we found the same thing.

Our data shows a low to moderate correlation between cheating and drunkenness, which may suggest that the more alcohol you consume the more dishonest you become. Were the participants actually more dishonest? One could argue that perhaps that they were less capable of completing the task while intoxicated. Of course, we’ll need to keep looking into the possibility. And you can, too. Next time you are out with some friends, you might want to take a few minutes and conduct an “experiment” on your own.

~Jennifer Fink~

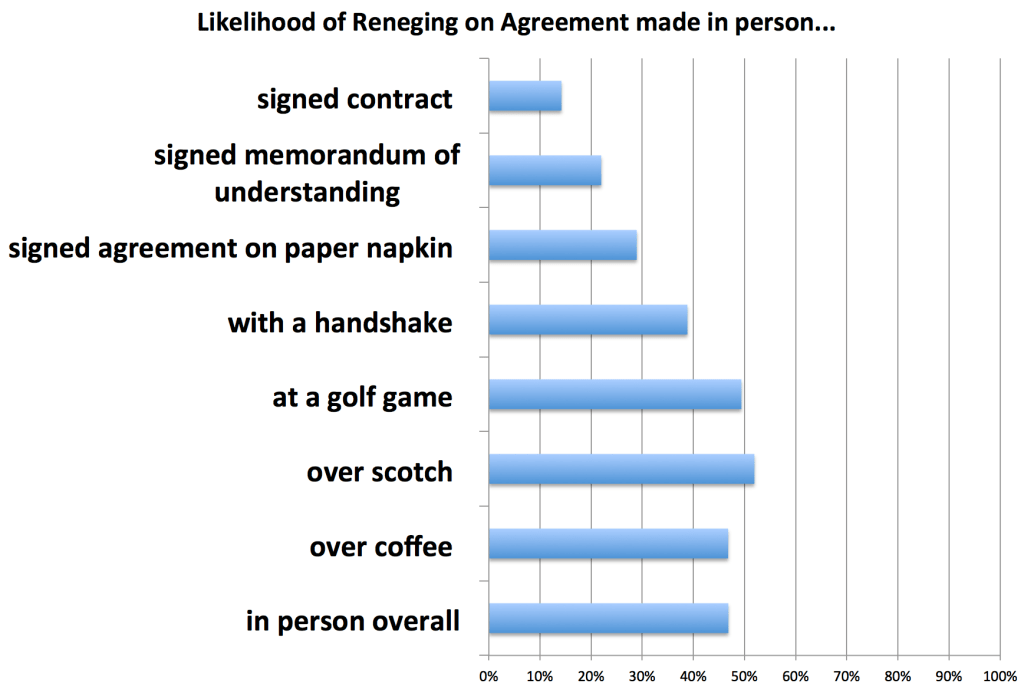

Backing Down From Agreements–Results

Imagine that you are shopping for a car, find a seller, and agree to purchase his car in a couple of days. The day before the sale, you find a better deal on a different car. Under what conditions would you renege on your original agreement? Would it be easier if your original agreement was made, so over the phone? Or over coffee?

Last week we put out a survey to find out, and here are the results:

As you can see, people have the hardest time reneging on deals made in person (compared with phone and email), and we have much less of a problem reneging deals made via a car dealer relative to one that was mediated by a mutual friend.

Zooming in on in-person agreements, we see here that agreements made over scotch and golf seem most likely to be reneged on, whereas we see significant improvement over various, even rudimentary, forms of signed contracts (napkin).

So next time you’re out selling a car, make sure at least to bring a napkin and pen with you, and next time you’re out buying a car, don’t sign anything unless you absolutely have to!

p.s here is an interesting academic paper related to this topic

Medical Gray Zones

Michael Jackson died of cardiac arrest on June 25, 2009. Recently, a hearing started regarding his former personal physician Conrad Murray. In this hearing the physician is accused of involuntary manslaughter, negligence, and administration of a dangerous and unnecessary cocktail of medications that accelerated the superstar’s death.

While I won’t argue for the physician’s innocence, I do think we should ask – how common is the tendency to prescribe patients what they want? Is this a singular incident, a case of a drug-pushing “bad apple,” or could there be more general forces at play?

What I hear from my physician friends is that they feel tremendous pressure to please their patients, and they know that if they don’t give them what they want, some other physician will (or at least this is how they justify their overprescription).

A common case of this sort is the case of the influenza virus. When patients contract the flu, they go to their doctors, feeling miserable and begging for help. Doctors know that they shouldn’t prescribe anything for their viral patients (and that the best thing to do is nothing), but they feel a pressure to give the patients something as they walk out the door. And so, they prescribe antibiotics, which don’t treat the flu but do build up drug-resistant bacteria that may cause trouble in the future.

Doctors in this situation face a conflict of interest, between what the patient wants from them, what is good for their own wallet (to keep the patient happy), and what is the right medical thing to do. Moreover, the situation is not perfectly clear because while it is unlikely that the patient has a bacterial infection (one where antibiotics could help) it is still possible – creating a gray zone of medical practice.

The thing about medical gray zones is that they become grayer, more blurred, when patients are more powerful or high-profile. The minute a doctor has a patient like Michael Jackson who is wealthy and used to getting his way, the pressure to succumb has to be much higher.

In thinking about Michael Jackson’s physician, consider this. It’s easy to find someone guilty and lay the blame solely on that individual, one man who shamefully deviated from the standard of care, but it’s much more challenging to put ourselves in his position and think about what we would have done if we were in his position. I suspect we too would have prescribed those meds.

P.S. I can’t believe that I am writing a blog about Michael Jackson

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like