The Meaning of Happiness Changes Over Your Lifetime

The following is a scientific and personal article written by CAH member Troy Campbell about happiness.

The following is a scientific and personal article written by CAH member Troy Campbell about happiness.

One lovely afternoon, I began chatting to my grandpa. I was completely unaware he was about to say something that would change my view of happiness forever.

In the middle of our conversation, I felt a lull so I pulled out the classic question. “If you could have dinner with one person, living or dead, who would it be?” I couldn’t wait to talk about my long list of dead presidents, dead Beatles, dead scientists, and a really cute living movie star. But I was also really eager to hear what he’d say.

Then he simply answered, “My wife.”

I immediately assured him it’s not necessary for him to answer like that. We all knew he loves his wife, whom he eats dinner with every night and was currently over in the other room playing cards.

He still insisted, “My wife. I’d have a nice dinner with my wife.”

“Alright,” I said, maybe a little too snappy, “Someone other than your wife.”

“Well okay, it would be my good friend and neighbor, Bill,” He replied.

The I became a little angry and pleaded, “Come on, you wouldn’t pick like John Lennon or Abraham Lincoln or FDR? He was alive when you were, right?”

“No. I’d pick Bill.”

I was just about to explain the point of the game again when it hit me. He already understood the game, and he was not trying to mess with me. What would make him most happy would be to have the same meal he has everyday, with the woman he’s been married to for 50 years.

Happiness to him was ordinary.

***

Over the past years, the interest in happiness has exploded. Everyone seems to want to be happy, read about how to be happy, or listen to Pharrells’ hit song, “Happy.” In response, researchers and gurus have been trying to feed everyone’s interest in happiness by pumping out new studies and New York Times bestsellers.

However, there’s been one factor that’s been missing in all this happiness discussion and in retrospect, it seems ridiculously obvious. That factor is age. As the story of my grandfather vividly displays, at different ages, we are interested in very different kinds of happiness.

Two young psychologists have recently stepped onto the scene and started to explain how happiness varies over the lifetime. Amit Bhattacharjee of Dartmouth University and Cassie Mogilner of the University of Pennsylvania find that the young find happiness and self-definition through extraordinary experiences, like meeting a celebrity. In contrast, older adults find happiness and self-definition through everyday experiences, like dinner with a best friend or wife.

To fully illustrate this concept, consider any family vacation. Think about how difficult it always is to make both the children and parents happy. This is because happiness means something different to younger and older members of the family.

The young crave the extraordinary. They long to bungee jump off a cliff, find a celebrity, and post a stylized Instagram photo that exaggerates the extraordinariness of the moment. Youth culture embraces the concept the of Yolo — “You Only Live Once” — which is just a modern (and arguably more annoying) way to say “carpe diem,” which is just a Latin way to say “seize the day.” Yolo is not something new; it’s just a rebranding of the youth mindset that’s always been around.

In contrast, older people tend to find happiness and define themselves in the ordinary experiences that comprise daily life. So, on vacation, parents often just want to spend time as a family. They want to have a nice family dinner and play card games.

What’s important about Bhattacharjee and Mogilner’s happiness hypothesis is that it is a psychological hypothesis rather than a cultural hypothesis. The scientists argue that with fewer days left in their lives, people start to focus on daily experiences and close-knit friendships. And that’s exactly what the researchers find through a controlled experiment. When they took 20-somethings and made them feel as if their brains would stop optimally functioning at age 40 (as opposed to age 80), the 20-somethings felt like they had less time left and were more interested in everyday happiness activities. They end up acting more like older people.

It’s worth noting that these findings greatly contrast the “Bucket List” hypothesis, the idea that as people feel their days are running out, they are motivated to do the extraordinary. For instance, in the film The Bucket List, two aging men strive to have the most extraordinary experiences possible. Though these cases do exist in society, they may be the exception. In general the rule is that as people feel like they are aging, they turn away from the extraordinary and, like my grandfather, focus on the everyday.

***

So if happiness is as important a goal in life as American culture makes it seem, we need to understand how age affects it. Only then can we know how to better treat our families, communities, and citizens of all ages. Only then will we all be happy, even if happy will mean different things to different people at different stages of their lives.

Ask Ariely: On Happy Money, Splitting Bills, and Unintended Stalking

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have worked very hard for most of my life, and I am getting to feel more secure and comfortable. But I don’t feel as happy as I expected, given all my achievements and financial success. I am not one of those hippies who think that money is not important, but it feels like something is missing. What am I doing wrong?

—Matt

Don’t worry. The fact that your financial achievements have not brought you contentment does not mean that you’re a hippie. Social scientists have long been troubled by the finding that people basically think money will bring them happiness but it does so less than they expect.

There are two possibilities: First, that money cannot buy happiness. Second, that money can buy some happiness, but people just don’t know how to use it that way. The good news is that this seems to be the correct answer.

In their fascinating book “Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending,” Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton say there are two ways to get more happiness out of our money. The first is to buy less stuff and more experiences. We buy a sofa instead of a ski trip, not taking into account that we will get used to the sofa very quickly and that it will stop being a source of happiness, while the vacation will likely stay in our minds for a long time.

Second, and more interesting, Drs. Dunn and Norton demonstrate that we just don’t give enough money away. Which of these would make you happier: buying a cup of fancy coffee for yourself, buying one for a stranger, or buying one for a good friend? Buying a cup of coffee for yourself is the worst. Buying for a stranger will linger in your mind and make you happier for a longer time, and buying for a friend is the best—it would also increase your social connection, friendship and long-run happiness.

So money can buy happiness—if we use it right.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m going to an out-of-town concert next month with friends and, as usual, I ended up organizing everything, booking a hotel room and fronting the money. When I’ve done this with groups in the past, I always end up spending the most on shared expenses, because they are never divided up evenly.

Perhaps I’m afraid to ask for large amounts of money, even though these are the true expenses that should be shared by everybody. What can I do to make sure that the bill for this upcoming show is split fairly?

—Scott

This is a question, in part, of how much you care about splitting the expenses evenly and how much responsibility you’re willing to take to improve the situation. I assume you’re willing to take this responsibility, so I suggest that you collect money from everyone in advance and pay all bills from this pool of money (and add 20% just in case, because we often don’t take all contingencies into account).

This way, everyone will pay the same amount, and bill-splitting will never come up. If there’s extra money, keep it for next year, or buy everyone a small gift to better remember the vacation.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I have sometimes found myself walking behind a woman at night in an unsafe place and going in the same direction. Even though there is some distance between us, I can feel the doubt and worry in her mind. How do I handle this situation? Should I stop or say something? I have places to be, too, but clearly I don’t want the woman to feel unsafe.

—Steve

Simply pick up your cell phone and call your mother. In the world of suspicion, nobody who calls his mother at night could be considered a negative individual.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Understanding Ego Depletion

From your own experience, are you more likely to finish half a pizza by yourself on a) Friday night after a long work week or b) Sunday evening after a restful weekend? The answer that most people will give, of course, is “a.” And in case you hadn’t noticed, it’s on stressful days that many of us give in to temptation and choose unhealthy options. The connection between exhaustion and the consumption of junk food is not just a figment of your imagination.

And it is the reason why so many diets bite it in the midst of stressful situations, and why many resolutions derail in times of crisis.

How do we avoid breaking under stress? There are six simple rules.

1) Acknowledge the tension, don’t ignore it.

Usually in these situations, there’s an internal dialogue (albeit one of varying length) that goes something like this:

“I’m starving! I should go home and make a salad and finish off that leftover grilled chicken.”

“But it’s been such a long day. I don’t feel like cooking.” [Walks by popular spot for Chinese takeout] “Plus, beef lo mein sounds amazing right now.”

“Yes, yes it does, but you really need to finish those vegetables before they go bad, plus, they’ll be good with some dijon vinaigrette!”

“Not as good as those delicious noodles with all that tender beef.”

“Hello, remember the no carbs resolution? And the eat vegetables every day one, too? You’ve been doing so well!”

“Exactly, I’ve been so good! I can have this one treat…”

And so the battle is lost. This is the push-pull relationship between reason (eat well!) and impulse (eat that right now!). And here’s the reason we make bad decisions: we use our self-control every time we force ourselves to make the good, reasonable decision, and that self-control, like other human capacities, is limited.

2) Call it what it is: ego-depletion.

Eventually, when we’ve said “no” to enough yummy food, drinks, potential purchases, and forced ourselves to do enough unwanted chores, we find ourselves in a state that Roy Baumeister calls ego-depletion, where we don’t have any more energy to make good decisions. So–back to our earlier question–when you contemplate your Friday versus Sunday night selves, which one is more depleted? Obviously, the former.

You may call this condition by other names (stressed, exhausted, worn out, etc.) but depletion is the psychological sum of these feelings, of all the decisions you made that led to that moment. The decision to get up early instead of sleeping in, the decision to skip pastries every day on the way to work, the decision to stay at the office late to finish a project instead of leaving it for the next day (even though the boss was gone!), the decision not to skip the gym on the way home, and so on, and so forth. Because when you think about it, you’re not actually too tired to choose something healthy for dinner (after all, you can just as easily order soup and sautéed greens instead of beef lo mein and an order of fried gyoza), you’re simply out of will power to make that decision.

3) Understand ego-depletion.

Enter Baba Shiv (a professor at Stanford University) and Sasha Fedorikhin (a professor at Indiana University) who examined the idea that people yield to temptation more readily when the part of the brain responsible for deliberative thinking has its figurative hands full.

In this seminal experiment, a group of participants gathered in a room and were told that they would be given a number to remember, and which they were to repeat to another experimenter in a room down the hall. Easy enough, right? Well, the ease of the task actually depended on which of the two experimental groups you were in. You see, people in group 1 were given a two-digit number to remember. Let’s say, for the sake of illustration, that the number is 62. People in group two, however, were given a seven-digit number to remember, 3074581. Got that memorized? Okay!

Now here’s the twist: half way to the second room, a young lady was waiting by a table upon which sat a bowl of colorful fresh fruit and slices of fudgy chocolate cake. She asked each participant to choose which snack they would like after completing their task in the next room, and gave them a small ticket corresponding to their choice. As Baba and Sasha suspected, people laboring under the strain of remembering 3074581 chose chocolate cake far more often than those who had only 62 to recall. As it turned out, those managing greater cognitive strain were less able to overturn their instinctive desires.

(Photo: PetitPlat)

This simple experiment doesn’t really show how ego-depletion works, but it does demonstrate that even a simple cognitive load can alter decisions that could potentially have an effect on our lives and health. So consider how much greater the impact of days and days of difficult decisions and greater cognitive loads would be.

4) Include and consider the moral implications.

Depletion doesn’t only affect our ability to make good decisions, it also makes it harder for us to make honest ones. In one experiment that tested the relationship between depletion and honesty, my colleagues and I split participants into two groups, and had them complete something called a Stroop task, which is a simple task requiring only that the participant name aloud the color of the ink a word (which is itself a color) is written in. The task, however, has two forms: in the first, the color of the ink matches the word, called the “congruent” condition, in the second, the color of the ink differs from the word, called the “incongruent” condition. Go ahead and try both tasks yourself…

The congruent condition: color matches word.

The incongruent condition: color conflicts with word.

As you no doubt observed, naming the color in the incongruent version is far more difficult than in the congruent. Each time you repressed the word that popped instantly into your mind (the word itself) and forced yourself to name the color of the ink instead, you became slightly more depleted as a result of that repression.

As for the participants in our experiment, this was only the beginning. After they finished whichever task they were assigned to, we first offered them the opportunity to cheat. Participants were asked to take a short quiz on the history of Florida State University (where the experiment took place), for which they would be paid for the number of correct answers. They were asked to circle their answers on a sheet of paper, then transfer those answers to a bubble sheet. However, when participants sat down with the experimenter, they discovered she had run into a problem. “I’m sorry,” the experimenter would say with exasperation, “I’m almost out of bubble sheets! I only have one unmarked one left, and one that has the answers already marked.” She explained to participants that she did her best to erase the marks but that they’re still slightly visible. Annoyed with herself, she admits that she had hoped to give one more test today after that one, then asks a question: “Since you are the first of the last two participants of the day, you can choose which form you would like to use: the clean one or the premarked one.”

So what do you think participants did? Did they reason with themselves that they’d help the experimenter out and take the premarked sheet, and be fastidious about recording their accidents accurately? Or did they realize that this would tempt them to cheat, and leave the premarked sheet alone? Well, the answer largely depended on which Stroop task they had done: those who had struggled through the incongruent version chose the premarked sheet far more often than the unmarked. What this means is that depletion can cause us to put ourselves into compromising positions in the first place.

And what about the people, in either condition, who chose the premarked sheet? Once again, those who were depleted by the first task, once in a position to cheat, did so far more often than those who breezed through the congruent version of the task.

What this means is that when we become depleted, we’re not only more apt to make bad and/or dishonest choices, we’re also more likely to allow ourselves to be tempted to make them in the first place. Talk about double jeopardy.

5) Evade ego-depletion.

There’s a saying that nothing good happens after midnight, and arguably, depletion is behind this bit of folk wisdom. Unless you work the third shift, if you’re up after midnight it’s probably been a pretty long day for you, and at that point, you’re more likely to make sub-optimal decisions, as we’ve learned.

So how can we escape depletion?

A friend of mine named Dan Silverman once suggested an interesting approach during our time together at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, which is a delightful place for researchers to take a year off to think, plan, and eat very well. Every day, after a rich lunch, we were plied with nigh-irresistible desserts: cheesecake, chocolate tortes, profiteroles, beignets—you name it. It was difficult for all of us, but especially for poor Dan, who was forever at the mercy of his sweet tooth.

It was daily dilemma for my friend. Dan, who was an economist with high cholesterol, wanted dessert. But he also understood that eating dessert every day was not a good decision. He contemplated this problem (along with his other academic interests), and concluded that when faced with temptation, a wise person should occasionally succumb. After all, by doing so, said person can keep him- or herself from becoming overly depleted, which will provide strength for whatever unexpected temptations lie in wait. Dan decided that giving in to daily dessert would be his best defense against being caught unawares by temptation and weakness down the road.

In all seriousness though, we’ve all heard time and time again that if you restrict your diet too much, you’ll likely to go overboard and binge at some point. Well, it’s true. A crucial aspect of managing depletion and making good decisions is having ways to release stress and reset, and to plan for certain indulgences. In fact, I think one reason the Slow-Carb Diet seems to be so effective is because it advises dieters to take a day off (also called a “cheat” day–see item 4 above), which allows them to avoid becoming so deprived that they give up entirely. The key here is planning the indulgence rather than waiting until you have absolutely nothing left in the tank. It’s in the latter moments of desperation that you throw yourself on the couch with the whole pint of ice cream, not even making a pretense of portion control, and go to town while watching your favorite tv show.

Regardless of the indulgence, whether it’s a new pair of shoes, some “me time” where you turn off your phone, an ice cream sundae, or a night out—plan it ahead. While I don’t recommend daily dessert, this kind of release might help you face down challenges to your will power later.

6) Know Thyself.

(Image: AnEpicDay)

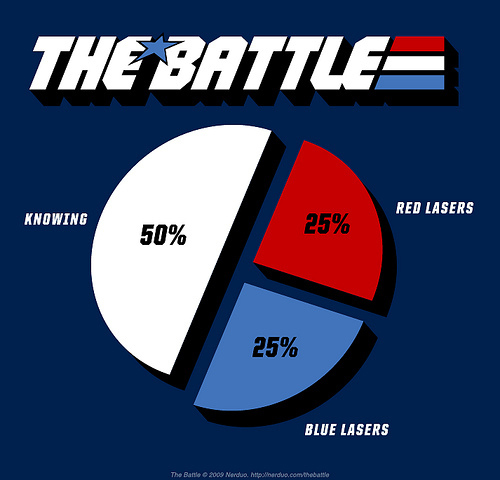

The reality of modern life is that we can’t always avoid depletion. But that doesn’t mean we’re helpless against it. Many people probably remember the G.I. Joe cartoon catch phrase: “Knowing is half the battle.” While this served in the context of PSAs of various stripes, it can help us here as well. Simply knowing you can become depleted, and moreover, knowing the kinds of decisions you might make as a result, makes you far better equipped to handle difficult situations when and as they arise.

This blog originally appeared on Tim Ferriss’ blog, here.

Burns and Happiness

The realization of how relative happiness is became very apparent to me some years ago when I was in the burn department.

One day a new patient came to the burn department — Miri, a teenage girl. Miri was 17 and her boyfriend just informed her that he was leaving her for someone else. As passionate as only teenagers can be, she went to the bathroom, slashed her wrists and poured bleach on them. As luck had it, when she was brought into the emergency room, Dr. Batya Yafe was there, an amazing woman and specialist in both plastic surgery and microsurgery who was able to reconstruct Miri’s blood vessels and take care of the damaged skin on her wrists.

A few weeks later Miri was a functional teenager again, but with second degree burns on her wrists. Relative to the rest of us, this was a relatively minor injury, but I am sure it was still very painful. The first few weeks were a serious adjustment for her – switching from being an active teenager in love to a patient in the burn department surrounded by these awful smells and many people in tremendous agony is not easy for anyone and particularly not for an idealistic teenager. The amazing thing was to see her a few weeks later and in the months to follow when she would come back to visit us. She seemed like a new and altogether person. She was happy, energetic, and with an appetite for life.

The scars that Miri carried on her wrists must have made her feel immensely different in the world outside the burn department, a constant reminder of her time spent in the burn department and the events that brought her there. I also suspect that these scars acted as a permanent reminder of what could have been, and her relative fortune in life. Was her newfound happiness related to the negative experience in the burn department? I imagine that Miri’s injury and her weeks in the burn department adjusted her perspective on life. Both the struggle she had with her burns, and the comparison to the other people in the burn department must have dwarfed her perceptions of her romantic trouble in comparison.

The burns on her wrists really helped Miri, and more generally I think that injuries that “work best” in giving people a new perspective on life are those that continuously act as a reminder of their relative happiness — even once the initial injury is over. Miri’s wrists, or losing a leg, for example, are promising on these grounds because the loss can act as a permanent reminder. And so are deep burns (the superficial ones are not as good because they can disappear with time). Lets be clear — I am not advocating burning people who are not very happy with their lives and letting them struggle with the pain and agony of burns, the slow recovery, and the comparison to other less fortunate individuals — but I do think that ironically such negative experiences can actually improve the outlook people have on life and their motivation for living.

So, as we plan for 2011 maybe we can find ways to be happy without any serious injuries.

Happy new year

Dan

Nicholas Christakis

Recently I wrote a short summary of Christakis’s research for Time magazine 100 people of 2009. Here is my summary of the research:

Social scientists used to have a straightforward, if tongue-in-cheek, answer to the question of how to become happy: Surround yourself with people who are uglier, poorer and shorter than you are – and who are unhappily married and have annoying kids. You will compare yourself with these people, and the contrast will cheer you up.

Nicholas Christakis, 47, a physician and sociologist at Harvard University, challenges this idea. Using data from a study that tracked about 5,000 people over 20 years, he suggests that happiness, like the flu, can spread from person to person. When people who are close to us, both in terms of social ties (friends or relatives) and physical proximity, become happier, we do too. For example, when a person who lives within a mile of a good friend becomes happier, the probability that this person’s good friend will also become happier increases 15%. More surprising is that the effect can transcend direct links and reach a third degree of separation: when a friend of a friend becomes happier, we become happier, even when we don’t know that third person directly.

This means that surrounding ourselves with happier people will make us happier, make the people close to us happier – and make the people close to them happier. But social networks don’t transmit only the good things in life.

Christakis found that smoking and obesity can be socially infectious too. If his thesis proves out, then the saying that you can judge a person by his or her friends might carry more weight than we thought.

Valentine’s Blog

Given Valentine’s Day and the state of the market, let’s consider which approach to finding love is better: 1) the free market system where everyone can find their own date and figure out who and what is best for themselves; or 2) a regulated market where your parents, family, or perhaps some kind of matchmaker have a say. This may be an impractical question these days (how many people let their mothers set them up?), but this is still a complex problem that’s been discussed for millennia, without any apparent solution. But here’s a boon for anyone who is starting to lose hope of finding love: a study that shows the importance of commitment to happiness.

The world of dating has grown increasingly complex, we have online dating, speed dating, casual dating, traditional dating (I think it’s still around anyway), and so on. The problem is, that with so many options, commitment to a relationship becomes difficult—you never know if there’s someone more perfect for you just around the corner. In a world where switching partners is difficult, people are likely to hang on and attempt to work things out. But in a world where it’s easy, or seems easy, to switch partners, people are likely to give up when things first go wrong. And yet, the ever-present temptation that there is someone out there who is better can be incredibly devastating to our personal happiness.

So we have to wonder then, how important is commitment? Dan Gilbert and Jane Ebert conducted a study with this question in mind using photography. In their experiment, they gave students a short course in taking black and white photos and taught them how to develop their pictures in the darkroom. Half the people were told that they could pick one of their pictures to be professionally enlarged and developed, which they could then keep. The other half were told to pick two pictures to keep, and that they could change their minds until the minute that the film was sent off. These people had a continual temptation to change their choices, so they had time to consider and reconsider which of their prints were the best.

Later, each participant was asked to rate their level of happiness with their prints. Guess who was happier, those who chose a photo and stuck with it, or those who had flexibility and time to make the perfect selection? As it turned out, the people who could alter their choices were much less happy than the first group. The principle behind this is that when we have to deal with a certain reality, we get used to it and often come to prefer it. But if we think we can change it, we don’t force ourselves to cope, so inevitable imperfections—whether in people or in pictures—can drive us to distraction. And the same thing happens with marriage. If we think of marriage as an open market and always have half an eye on other options, we’ll be less likely to be happy.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like