Regret

Imagine that you have a flight at 8:00 in the morning. Which would be worse, arriving at the gate, breathless, at 8:02, just after they’ve closed the door, or at 10:00, thanks to a couple unplanned delays in your morning. Obviously, the first scenario would cause far more misery, but why? Either way you’re stuck at the airport until the next flight, eating the same bad, overpriced food, missing whatever you were supposed to do after your planned arrival, whether that’s meetings or a stroll on the beach.

The difference between the two scenarios is the intensity of the regret you would feel—a great amount in the former and a lot less in the latter. As it turns out our happiness frequently depends not on where we are at the moment, but how easily we perceive we might be elsewhere, or in another, better situation. With the missed flight, you’re in the airport either way, but when it’s a close call, you can think of a dozen little things that would have changed the situation, and each one brings a pang of regret. So, the closer we are to this other possibility, what we refer to as counterfactual, the unhappier we become.

While there are plenty of things in life that cause disappointment and aggravation, consider the case of Costis Mitsotakis, a resident of Sodeto, Spain, who was the only person in this 70 household village who did not receive a share of the $950 million lottery payoff. The story is this: every year the homemaker’s association of Sodeto sells tickets to all the residents, and in 2011, their number won first prize (shared with 1,800 other winning tickets, but still an immense payoff for a tiny, economically depressed town). When the townspeople heard the news, they ran outside, and were congratulated over a megaphone by their jubilant mayor. But soon it was discovered that one resident hadn’t bought a ticket—Mr. Mitsotakis, who had moved to Sodeto for a woman with whom things did not work out, was overlooked when the homemakers made their yearly rounds.

In this case, the counterfactual looms incredibly and painfully large. If only they hadn’t skipped his house or he had run into them at some point—the smallest earning from the lottery in the village was $130,000, and some won more than half a million dollars. If that wasn’t bad enough, the reminders of this alternative outcome will last for the rest of his life, or at least as long as he remains in Sodeto. Mr. Mitsotakis will be continually reminded of the tiny difference in events between his life now and what it would have him. If I were him, maybe I would simply move. This would probably decrease his happiness in the short term, but in the long run I think his life would be much better, and much less regretful.

So, next time you miss a flight, are first in line after tickets sell out, or get stuck in traffic after trying out an alternative route home, just remember, your situation may be frustrating, but it’s not like you lost half a million dollars and it is not as if you will keep on remembering this for the rest of your life.

Supply, Demand, and Valentine’s Day

Want to know how to ensure your wife or girlfriend’s satisfaction with her Valentine’s Day present? Over breakfast, casually mention that recent census data shows women outnumber men in your area, and that men are apparently a scarce commodity (or maybe just the first part).

Why would this matter? Well, according to a recent study from the University of Minnesota, perceived gender ratio affects economic behavior in both men and women. Regarding your sweetheart’s present, after female participants read an article describing a dearth of men in the local population, the amount of money they expected a man to spend on dinner, Valentine’s Day, and engagement rings decreased (and likewise, they expected men to woo them more lavishly when there were reportedly more men than women).

This sort of news had a complementary effect on men. When male participants read an article indicating an excess of men in the population and then answered questions about monthly spending habits, they reported they would borrow 84% money more and save 42% less. When the article reversed the ratio, men accordingly borrowed less and saved more. (Unlike men, women’s spending habits were not altered by the reported population inequality, only their expectations were.)

Moreover, an apparent discrepancy in gender was all it took to increase men’s willingness to make financially riskier decisions. In another experiment, participants were shown photos of groups of people: some where women outnumbered men, some where men outnumbered women, and some with an equal number of each. Afterwards, experimenters asked participants whether they would rather be paid the following day, or wait for a greater amount in a month. The result? After viewing photographs graced by fewer women, men were much more likely to choose $20 the next day over waiting a few weeks for $30.

As it turns out, researchers discovered that these results are born out in real populations too: In Columbus, Georgia, there are 1.18 single men for every single woman, and the average consumer debt is $3,479 higher than it is 100 miles away in Macon, where there are 0.78 single men for every woman.

So for those of you who are single and looking to find a match, here’s a little help from the US Census Bureau. Ladies, you’ll want to try your luck in the blue areas; guys, your best bet is in the red.

Oh, and Happy Valentine’s Day.

Special Deals at Whole Foods

Jared Wolfe, one of the students working with me, took the following pictures at Whole Foods a few days ago. They illustrate amazing creativity in defining what the term “a deal” means.

1) Regular price is $1.99 and the Sale price is? Two of the same item for $5 — which according to Whole Foods’ quick calculation is a savings of $1.02. Amazing.

2) Regular price is $3.99 and the Sale price is? $3.99 — thankfully this time they did not add any amount to the savings.

What I am wondering is how many people just look for the orange tags and the Sale signs without even looking at the details. I suspect that this is very common, particularly in a busy and hectic grocery store and particularly when we buy many items that each of them by itself is not very expensive.

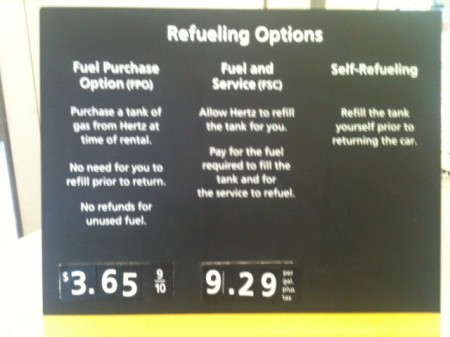

Refueling Options at Hertz

I got this picture this week. What is interesting about this price menu is that the “Fuel and Service,” priced at $9.29, is so off the scale (and so outrageous) that perhaps it makes the pre-paid option of $3.65 look attractive. After all it is about 1/3 the price of the Fuel and Service.

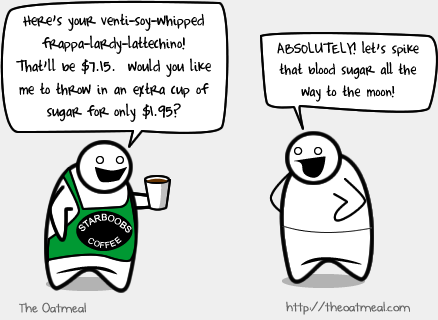

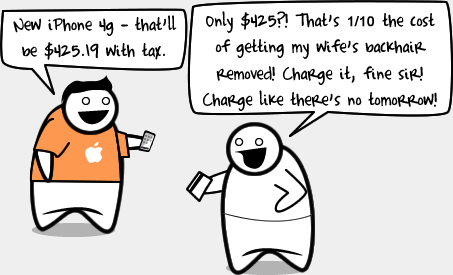

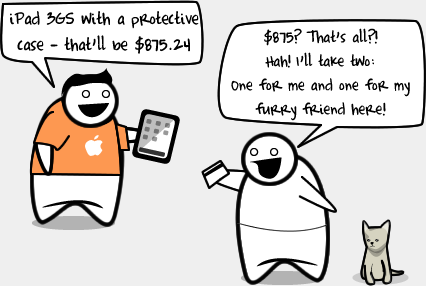

This Is How I Feel About Buying Apps

I came across a funny cartoon the other day that captures an interesting aspect of our purchasing behavior. We are perfectly willing to spend $4 on coffee (for some of us this is a daily purchase), or $500 on devices that you can argue we don’t really need. However, when it comes to buying digital items, such as apps, most of which are priced at $1, we suddenly get really cheap. Why?

http://theoatmeal.com/blog/apps

Here are some reasons. The first is that we are anchored by the price of categories, so when we think about lattes, we compare only across beverages. When we think about apps, we only compare across digital downloads. Thus, when we think about buying a $1 app, it doesn’t occur to us to ask ourselves what the pleasure that we are likely to get from this $1 app — or even what is the relative pleasure that we are likely to get from this app compared with a $4 latte. In our minds, those two decisions are separate.

So now the question becomes, why is the price anchor for apps so low? I think the answer to this is that we have been trained with the expectation that apps should be free. Having lots of free apps on the App Store is clearly advantageous for Apple, because it makes their devices more attractive. However, because FREE! is such a special, exciting price level, it makes the thought of paying even $1 for an app into an agonizing decision.

I think this could have been avoided. Imagine if instead of offering free apps on day one, Apple instead created a really low minimum price–say $0.15. Lots of people would still go for Apps at this price, but instead of being anchored to the idea that apps should be free, we would be anchored to the idea that apps should cost something. Then paying more (maybe even $2) for an app would be a simpler step, maybe one that we could take as easily as paying $4 for a latte.

Easing the Pain This Holiday Season

The image (and jingle) of the bells of Salvation Army volunteers is almost as synonymous with the holiday season as Santa Claus himself. However, the New York Times reported last month that a change may be coming to a street corner near you; the charity has begun testing the use of a digital donation system called Square that would allow passersby to donate via credit card, rather than have to worry about scrambling for loose change.

The image (and jingle) of the bells of Salvation Army volunteers is almost as synonymous with the holiday season as Santa Claus himself. However, the New York Times reported last month that a change may be coming to a street corner near you; the charity has begun testing the use of a digital donation system called Square that would allow passersby to donate via credit card, rather than have to worry about scrambling for loose change.

The article mentions two potential benefits of this kind of system. First, people are less likely to carry cash on them as they were in the past, and so Square’s credit card system provides people with a quick, simple, and convenient way to donate when they don’t have any real money handy (and with 1 in 7 Americans carrying at least 10 credit cards, this shouldn’t be a problem). Second, a credit card system would be safer because donations would not be vulnerable to theft like money in the kettle has always been.

Still, this credit card system may unintentionally have another significant benefit: it may lead people to want to donate more money than they would otherwise. There is a concept in behavioral economics known as the “pain of paying.” Simply put, it hurts us to spend (and part with) our money. And since buying things with a credit card is a less direct, less tangible way to part with money than using cash, it can feel less painful, and therefore lead people to spend more.

Assuming that this effect generalizes from buying products to donating to charities, Square’s credit card system may actually lead to larger total donations for the Salvation Army, whether it is because more people decide to donate, or because more money is donated by each individual. (Not to mention the possibility that people may feel silly choosing “loose change”-style amounts (e.g., 35 cents) to donate via credit card, and so may round up to the whole dollar for that reason alone).

So Square’s credit card system may, through behavioral economics, lead people to be more generous with their donations to the Salvation Army. If the Salvation Army uses this new system and winds up faring well, perhaps other charities should take note and consider implementing such a system as well.

Have a happy holiday season, everyone! And remember that doing the most good may be just a swipe away.

~Jared Wolfe~

Carreker Happens

Did you know that free checking works by exploiting the everyday cash shortages of the poorest in our country? There is a company that dresses it up and sells it to banks.

Did you know that free checking works by exploiting the everyday cash shortages of the poorest in our country? There is a company that dresses it up and sells it to banks.

I recently moved to Durham from Boston, and as it goes I had to set up new accounts to establish services for my loft. Part of this task involved deciding on a bank to take my deposits and facilitate payments. I set up a simple matrix to help me decide on a bank that included two simple categories: proximity and fees. There were plenty of banks within a reasonable distance to me, but where my matrix failed was in the fee category.

Apparently, “free” checking accounts are now ubiquitous. Sounds good, right? Not for me. I work in behavioral economics. Free checking looks to me like Winnie the Pooh walking out of a XXX movie theater. In other words, innocence doesn’t have sweat on its sneaky brow. There is no such thing as free, it’s just hiding. Cost can be intangible, but this is not the case with free checking. So, who pays for free checking for all of us? Consumers with illiquidity issues, and these are the people who need their money the most. There cannot be a worse target. What used to be called a penalty fee for overdrafting an account is now called a convenience fee or value added service. How appealing. These fees add up and happen frequently enough to offer free checking.

I had to ask, from whom are all of these banks getting this bright idea? I found that banks of all sizes offer free checking, so this tells me that there must be a third party facilitator. I searched for B2B bank products under the granddaddy of all bank facilitators, Fiserv, and smiling at me like Miss America with AIDS was none other than Carreker.

Carreker calls it Revenue Enhancement and it is a very attractive service for any bank that puts money before fairness to consumers. Carreker enables a bank to collect on penalty fees and clear transactions in real time, which is how Carreker can boast that the bank will see immediate results. It is not because they have done something truly beneficial for the customer. Most of all, Carreker actually controls the overdraft decisions. They have their hand on the penalty revenue throttle. As a customer’s account goes negative, they can allow the customer to overdraft not once but for several transactions, thus incurring high fees. Senior Vice President and Managing Director of Carreker Revenue Enhancement, Jeff Burton, claims that the “fee income market is fine” provided that you [the bank] position yourself with Carreker to share in the wealth.

Aggressive revenue seeking has changed the manner of normal operations into more of a production model. Banks now call overdraft penalties by a new name: exception revenue. Furthermore, they want you to see it as if they are doing you a favor and that it is okay, in fact perfectly fine as you now know, if you need to overdraft your account. The negative connotation has been replaced by the notion that your bank is forgiving and would never prevent you from making that gratifying purchase. It is not right to allow customers to pay an average of 9 X $30 if they miscalculate their account balance. Alas, Carreker does not stop with their exception revenue system.

Burton states that they have gone as far as to create a special framework for one of their clients to allow them to profit from payday loans. This is what they call their approach to increase overall revenue and customer utilization. I’m not sure about you, but I am not here to be “utilized.” Carreker will continue to innovate new ways to capitalize on the hardships of consumers. Most frighteningly, they are not just an idea firm because they actually provide the framework, algorithms, and integration to allow the bank to carry on these evil deeds.

For what’s it’s worth, I changed my decision matrix to seek a bank that had all around low fees, so I can avoid living off of the money of people who desperately need it. I’m still looking.

~Myles Leighton~

Asking the right and wrong questions

From a behavioral economics point of view, the field of financial advice is quite strange and not very useful. For the most part, professional financial services rely on clients’ answers to two questions:

- How much of your current salary will you need in retirement?

- What is your risk attitude on a seven-point scale?

From my perspective, these are remarkably useless questions — but we’ll get to that in a minute. First, let’s think about the financial advisor’s business model. An advisor will optimize your portfolio based on the answers to these two questions. For this service, the advisor typically will take one percent of assets under management – and he will get this every year!

Not to be offensive, but I think that a simple algorithm can do this, and probably with fewer errors. Moving money around from stocks to bonds or vice versa is just not something for which we should pay one percent of assets under management.

Actually, strike that. It’s not something we should do anyway, because making any decisions based on answers to those two questions don’t yield the right answers in the first place.

To this point, we’ve run a number of experiments. In one study, we asked people the same question that financial advisors ask: How much of your final salary will you need in retirement? The common answer was 75 percent. But when we asked how they came up with this figure, the most common refrain turned out to be that that’s what they thought they should answer. And when we probed further and asked where they got this advice, we found that most people heard this from the financial industry. Sort of like two months salary for an engagement ring and one-third of your income for housing, 75 percent was the rule of thumb that they had heard from financial advisors. You see the circularity and the inanity: Financial advisors are asking a question that their customers rely on them for the answer. So what’s the point of the question?!

In our study, we then took a different approach and instead asked people: How do you want to live in retirement? Where do you want to live? What activities you want to engage in? And similar questions geared to assess the quality of life that people expected in retirement. We then took these answers and itemized them, pricing out their retirement based on the things that people said they’d want to do and have in their retirement. Using these calculations, we found that these people (who told us that they will need 75% of their salary) would actually need 135 percent of their final income to live in the way that they want to in retirement. If you think about it, this should not be very surprising: If you add 8 hours (or more) of free time to someone’s day, they will probably not want to spend this extra time by going for long walks on the beach and watching TV – instead they may want to engage in activities that cost money.

You can see why I’m confused about the one-percent-of-assets-under-management business model: Why pay someone to create a portfolio that’s 60 percent too low in its estimation?

And 60% is if you get the risk calculation right. But it turns out the second question is equally problematic. To show this, we also asked people to tell us how much risk they were willing to take with their money, on a ten-point scale. For some people we gave a scale that ranges from 100% in cash on the low end of the risk scale and 85% in stocks and 15% in bonds on the high end of the risk scale. For other people we gave a scale that ranges from 100% in bonds on the low end of the risk scale and buying only derivatives on the high end of the risk scale. And what did we find? People basically looked at the scale and said to themselves “I am a slightly above the mean risk-taker, so let me mark the scale at 6 or 7.” Or they said to themselves “I am a slightly below the mean risk-taker, so let me mark the scale at 4 or 5.” In essence, people have no idea what their risk attitude is, and if they are given different types of scales they end up reporting their risk attitude to be very different.

So we have an industry that asks one question it’s giving the answer to, and a second question that assumes that people can accurately describe their risk attitude (which they can’t). This saddens me because, while I think that financial advisors are overpaid for the service they provide, in principle they could contribute much more, and they could even deserve their salary. But only if they start offering a more useful service, one that they are in the perfect position to provide. Money, it turns out, is incredibly hard to reason about in a systematic and rational way (even for highly educated individuals). Risk is even harder.

Financial advisors should be helping their clients with these tough decisions! Money is about opportunity cost. Every time we think about buying a car or going on vacation we should be asking ourselves what we won’t be able to afford in the future if we go ahead and make this purchase. And that’s where the financial advisor should come in.

It’s possible that the best financial advisors already do help in this way, but the industry as a whole does not. It’s still centered on the rather facile service of balancing portfolios, probably because that’s a lot easier to do than to help someone understand what’s worthwhile and how to use their money to maximize their current and long-term happiness.

The fact is that money is hard to think about and we do need help with making financial decisions. The financial consulting profession has an opportunity to reinvent itself to service this need. And if they do, it will be beneficial for both financial advisors and their clients.

——————–

A shorter version of this appeared at hbr.org

Help Me Today, I'll Help You Tomorrow

In the course of our lives, we come across countless opportunities to help others. The occasional homeless person or charity asks for a donation, or the Red Cross is collecting blood across the street. But most of the time, these opportunities present themselves through our social networks — simply because we interact most often with our friends. One important difference between helping friends and helping strangers is that we know our friends can pay us back in the future, whereas strangers can usually only pay it forward. Of course, all people are not able to help others to the same degree; some people have a lot to spare while others get by on a tighter budget.

In the course of our lives, we come across countless opportunities to help others. The occasional homeless person or charity asks for a donation, or the Red Cross is collecting blood across the street. But most of the time, these opportunities present themselves through our social networks — simply because we interact most often with our friends. One important difference between helping friends and helping strangers is that we know our friends can pay us back in the future, whereas strangers can usually only pay it forward. Of course, all people are not able to help others to the same degree; some people have a lot to spare while others get by on a tighter budget.

My friend Sevgi and I wondered whether people are more generous when others have the opportunity to help them back in the future, and whether people reciprocate based on the value of the gift they received. Our main questions were:

1) Do people give more when they know they may get something in return?

2) Do receivers care whether their gift is more valuable in an absolute or relative sense?

To look at these questions, we had people play a simple game as one of two players: lets call them player A and player B. We give $1 to player A and $100 to player B (they both see how much the other gets). Player A can send any amount (of his $1) to player B, and then player B decides how much (of his $100) to send back. In another version of the game, player B cannot give anything back.

Does player A send more money to player B when he knows that B can send money back? How much money does player B send back when player A sends nothing, some of his money, or even his entire dollar?

Looking at the results, we see that people are a) strategic when they offer money initially and b) reciprocating after they have been given money. On average, player A sends more to player B if he knows that B can send something back. And the more that player A sends to player B, the more he receives.

However, the amount sent back by player B does not depend on the absolute value of player A’s initial offer, but on the proportion of player A’s wealth that was offered. What does this mean? If player A has $50 instead of $1 and sends half of it to B ($25), he gets back almost the same amount of money from B as he gets after sending half of $1 (50 cents!).

So, what is the lesson du jour? It turns out that people with limited resources can gain just as much from acting altrustically as those who are well-endowed. Don’t get discouraged by a thin wallet when given the chance to help others — after all, it is your generosity that counts.

~Merve Akbas~

The Upside of Useless Stuff

There’s been plenty of talk lately –in these pages and elsewhere– about a new kind of capitalism. About creating things because they’re good for society. About understanding, as Michael Porter and Mark Kramer suggest (“Creating Shared Value,” HBR January-February 2011), that not all profits are created equal: Profits derived from making the world better are superior to those derived from the consumption of useless, or even harmful, junk.

At the risk of touching the third rail, I propose that getting people to want things they don’t really need may be far more valuable to society than we think.

Imagine that I started a business selling beautiful bottles of air for $10. I’d call them Respirer (res-pir-AY– it’s French!). My advertisements would laud Respirer’s purity, evoking bracing mountain air. (Fewer than 10 parts per trillion of particulate in every bottle!) Celebrities would endorse Respirer’s rejuvenating effects. (Kate Winslet starts every day with Respirer!) In a matter of months, department stores would be selling out, and spas would brag that their saunas piped in pure Respirer air.

Respirer would be a runaway hit. Of course, it would be just air, and in most places you could get all the reasonably high-quality air you wanted free. So how could this clearly useless product have a beneficial effect on the economy? It would motivate people. By hyping Respirer, I’d give consumers something to want, and in order to be able to afford it, they’d have to work. They’d have to be productive.

We often talk about how marketing’s job is to get us to want things and spend our money, sometimes foolishly. But that reflects only marketing’s output. Marketing also creates input: It spurs us to work to earn the money to buy the things we want.

Consider for a moment a world without marketing hype. One in which there’s nothing you really desire beyond what you need to live. There’s nothing your kids want; they don’t bug you every time you’re in the supermarket. How hard would you work in such a world? What would motivate you to work harder?

Now consider our current consumer environment: Multiply the desire for Respirer by thousands of products of varying levels of utility: iPads, leather couches, crystal martini glasses, cars, garden gnomes. It’s like having thousands of little motivational speakers hovering around us.

Suppose I’m a surgeon. Could it be that my desire for Respirer, and all this other stuff, would spur me to work harder? To innovate new procedures that would save lives and also enrich me personally? I suspect it’s very likely.

Let’s be clear. I don’t mean to say that marketing will save our economy. Or that marketing things we don’t need is the key to a prosperous planet. The line is narrow, indeed, between being motivated to work and mortgaging the future (both your own and society’s) to get stuff like bottled air.

Still, as we continue to redefine capitalism, let’s not discount the role of aspiration and the desire for incremental luxuries–things we want but don’t necessarily need. They can fuel productivity and thus have a valuable function in our economy.

Originally published in Harvard Business Review, May 2011.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like