I ______ a dollar?

As part of the PoorQuality: Inequality exhibition that is currently on display at the CAH, we are showing a piece of art by Jody Servon entitled “I ______ a dollar.” This piece started out as one hundred $1 bills stuck flat against the wall. The bills hung there in a simple, uniform shape, Washington after Washington. The money was there for the taking, but only if you needed it. Jody asked viewers to think about the value of a single dollar, to contemplate their “needs” in relation to their “wants.”

“My hope is for people to actively consider whether or not having this single dollar will make a difference in his or her life, or if they feel the dollar is better left for someone else who needs it more. Perhaps the invitation to take free money will eclipse the question of want vs. need.”

A week went by, and one dollar disappeared. Afraid that the piece would dissolve too quickly, one lab member replaced the missing dollar. The art was whole again. More time went by, and another lab member needed change for the vending machine. So she took five singles and left her $5 bill. We treated the piece as if it was our own, moving bills around but preserving its integrity. The wall of money remained, for the most part, intact.

We asked Jody about her expectations for the piece.

“Among the scenarios I considered were one person swiping all of the dollars on the first day, the dollars slowly disappearing one-by-one, someone rearranging the dollars in a different design, or somewhat disappointingly, the piece remaining on the wall untouched.”

But the wall did not remain untouched, and one day it encountered a group of guests who came in on a particularly quiet day and left with most of the money. Sure, we were a little annoyed; our precious wall had been ransacked. But that was its purpose, and we laughed it off. At least we had a good story, right?

Some time later, one of the ransackers returned. This time, the CAH was bustling, full of people and lively conversation. He walked in, saw the commotion, and hesitated for just a moment before telling us that he was hungry. We don’t have any food here, but there are plenty of restaurants down the street, we told him. Of course, he was not asking where he could buy food. We knew that. But none of us jumped up to offer what was left of the money hanging on the wall. It was art, after all.

Here we were, hosting an exhibit on “inequality,” and there was no doubt that this man lay farther down on the distribution of wealth than any of us. And in all of our musings on the exhibit, never did we think that we might find ourselves faced with the perfect case of actual inequality.

Until this moment, we had primarily used and conceived of the wall of bills as a cashier. Yes, we contemplated whether we needed or simply wanted a dollar. But most of us don’t need a dollar. In the end, this experience may be the ultimate experiment of our project. And we stumbled into it unintentionally, or rather, he stumbled into our gallery.

A collaboration between Dan Ariely & Aline Grüneisen

The PoorQuality: Inequality Exhibit will be up until the end of August (and we will see whether there are any dollar bills left).No Longer Gaga for Gaga?

Our very own Troy Campbell presents his research on desensitization via repetition, and (naturally) uses Lady Gaga as his experimental stimuli.

Our very own Troy Campbell presents his research on desensitization via repetition, and (naturally) uses Lady Gaga as his experimental stimuli.

Related articles

- How Shocking Will Others Find Lady Gaga? (psychologicalscience.org)

iPhone 5 or Samsung Galaxy S3?

My 2-year cell phone contract was up last month, and even before the date when I could opt for an upgrade, I began to experience the pain of indecision: which was it going to be – a Samsung Galaxy S3 or an iPhone 5? I was one of the only Android (HTC Evo) users in our Center for Advanced Hindsight team, and swayed by the rest of the group’s dedication to Apple, I was looking forward to switching to the new iPhone as soon as my contract was up. But I was not going to be able to befriend the newest iOS 6-adorned Siri until the iPhone’s release in a couple of months. In today’s impatient tech age, that is an eternity. My longing for an Apple clashed with my itching desire to get a new phone.

My 2-year cell phone contract was up last month, and even before the date when I could opt for an upgrade, I began to experience the pain of indecision: which was it going to be – a Samsung Galaxy S3 or an iPhone 5? I was one of the only Android (HTC Evo) users in our Center for Advanced Hindsight team, and swayed by the rest of the group’s dedication to Apple, I was looking forward to switching to the new iPhone as soon as my contract was up. But I was not going to be able to befriend the newest iOS 6-adorned Siri until the iPhone’s release in a couple of months. In today’s impatient tech age, that is an eternity. My longing for an Apple clashed with my itching desire to get a new phone.

After watching a hopeless number of face-off videos, reading about the features and specs of Galaxy S3 compared with the endless mock ups of the rumored iPhone 5, and even throwing the question around at dinner parties, I decided to come to my senses, listen to what research has to say, and make an irrationally rational decision. Though surely evidence from decades of research is not limited to the following considerations, I picked a number of conceptual tools from decision-making research that could help shed light on this quandary of iPhone vs. Samsung:

- Now vs. Later: I should pit my short-term interest in having a new smartphone now against my long-term interest in having an iPhone later. Temporal discounting suggests that we have the tendency to want things now rather than later, and delaying gratification depends on whether we are convinced that what will happen in the future is going to be better than what we can have now. In other words: howmuch better is this nebulous iPhone of the future when I could have this immediately awesome Galaxy S3? Given that the specs of Galaxy S3 are available but those of the iPhone 5 are not, it might be smart to bet for what is certain. (Winner: Galaxy S3)

- Misremembering the past vs. mispredicting the future: I can go with the certain specs of Galaxy S3, or potentially recall my past experiences with iPhones and decide accordingly. Sadly we are bad at remembering past feelings; rather than correctly weighing the positives and negatives we remember the peak moments and selected experiences. Since I am unable to accurately recall my past emotional states, then maybe I can imagine how much pleasure each of these phones could bring me in the future? Unfortunately, we are also notoriously bad at predicting the duration and intensity of future feelings. (Winner: Galaxy S3)

- Want vs. need: Do I want a new phone? Yes. Do I really need a new phone? No, because my old one is still in good shape. With the irresistible discounts of signing up for a new 2-year plan, I am conditioned by the cell phone market to switch to a new phone as soon as possible. This conditioning moves me from casually wanting a new device to absolutely needing it to survive (!). I feel that the longer I wait, the more I am giving up on a perceived opportunity. (Winner: wait until my current phone gives up, and then get an iPhone 5).

- Decoy options iPhone 4s vs. HTC Evo: In my indecision, I can introduce a third option that is asymmetrically dominated either by Galaxy S3 or iPhone 5. If I consider iPhone 4S as a potential option, it would (hopefully) be dominated by iPhone 5 but could still be superior to the Galaxy S3 with the ease of its use, compactness and such. If I am leaning more towards the Android options, then I can consider staying with HTC Evo as a potential third choice, and given that Galaxy S3 surpasses my old Android in nearly every domain, I would lean towards upgrading to Samsung. (Winner: Depends on the decoy option)

- Reactance to unavailability: The brands also complicate the issue as they control supply and increase demand by playing with the availability of their products as well as the timing of their release. This can create several types of responses:

- Since iPhone 5 is currently unavailable, I experience a pressure to select iPhone 4S which is a similar alternative. If I perceive this as a limitation on my freedom to choose, I might react by selecting a dissimilar option. (Winner: Galaxy S3)

- The unavailability of iPhone 5 could also lead me to perceive it as more desirable. (Winner: iPhone 5)

- Or I can just despise what I can’t have. (Winner of the sour grapes story: Galaxy S3)

So, what should I do? Given the considerations above, there is still no clear winner for me. Yes, I have the plague of newism: I run after the genuine, exciting proposition of the emerging trends and products. Yes, I know there is something good now, but possibly something better around the corner.

At the end of the day, I will toss a coin: not because it will settle the question for me, but because in that brief moment when the coin is in the air, I will suddenly know which side I hope to see when it lands in my palm. And besides, whether I purchase my new phone from Apple or from Samsung, I will stick to my commitment, almost immediately forget about the forsaken option, and justify my choice infallibly in retrospect.

~Lalin Anik~

Prada Overnight

After meeting her through a friend from graduate school, the editor of Harper’s Bazaar invited me to give a talk at the magazine headquarters. It was my first experience presenting at a fashion magazine and I suspect it may have been their first experience hosting an academic speaker. They were very gracious and interested (or at least they appeared to be), and they laughed where I hoped they would and asked thoughtful questions.

As a thank-you gift, they gave me a Prada overnight bag. Now, Apple products are the closest I have ever come to owning anything from a highly recognized brand, so acquiring this bit of couture was an interesting experience for me. As I made my way through JFK, I tried to decide whether I should hold the bag so that the triangular Prada logo was visible to other travelers or if I should keep it facing towards me. I quickly decided to keep the logo facing me, and began thinking about the role of brands in people’s lives.

We usually think of brands as signaling something to others. We drive Priuses to show that we are environmentally conscious or wear Nike to show that we’re athletic. In this case I didn’t want to send a signal to the world, but nevertheless I felt different, as if I were signaling something to myself—telling myself something about me and as a result of carrying the Prada bag.

Maybe this is the attraction of branded underwear. They are basically a private consumption experience, but my guess is that if I put on a pair of Ferrari underwear, even if nobody saw them, they would still make me feel differently somehow (Perhaps more masculine? Wealthier? Faster?).

The thing is, I realized I couldn’t just try to make myself feel better by imagining myself wearing Ferrari underwear. I would have to actually wear them in order to feel differently.

So brands communicate in two directions: they help us tell other people something about ourselves, but they also help us form ideas about who we are.

Why we really are distracted by shiny objects.

Choosing Brighter Instead of Tastier Candies May Be Good For You:

How Visual Properties of Choice Options Influence Our Decisions

by Mili Milosavljevic, Ph.D.

In 2009, Tropicana redesigned the packaging of its orange juice in an attempt “to reinforce the brand and product attributes [and] rejuvenate the category.” The company said that “for the first time, Tropicana… will be branded ‘100% orange’, which will be featured as a bold, new graphic on all packaging… [A] proprietary fresh cap… will be another visual signal of the brand’s natural, health benefits.” Less than 2 months after the redesign, dollar sales of Tropicana orange juice had dropped about 19% or $33 million, with competitors picking up Tropicana’s lost market share. The company’s response was to immediately bring back the previous version of packaging and determine what went wrong. Some of the surveyed consumers complained that they missed the old packaging and Tropicana was quick to attribute the flop to messing with the usual suspect: emotional bond that consumers had with the old packaging. Other consumers, however, noted that the redesign had made it more difficult to spot Tropicana on a store shelf or to differentiate it from other brands. This alternative explanation suggests that replacing the familiar, prominent, dark-green Tropicana brand name on the packaging, with a sleek, bright-green, 90-degree tilted version dwarfed by an enormous glass of orange juice that replaced the orange with a straw coming out of it caused some consumers to miss the brand and simply pick up another instead.

Is it plausible that simple visual features of choice options, such as a package’s color or brightness, influence consumers’ choices? Mili Milosavljevic, together with a team of vision scientists and neuroscientists, recently conducted a series of eye-tracking studies in which consumers made real choices between snack food items whose brightness of packaging was systematically varied. When consumers chose between items they prefer (such as a Snickers bar) and visually enhanced, i.e., brighter, but less preferred options (such as Sour Skittles), a significant portion of their choices was biased toward choosing the brighter, less liked, item. This visual saliency bias, or bias toward brighter-colored items, was even stronger when consumers made choices while being engaged in another cognitively demanding task, akin to talking on a cellphone while shopping in a grocery store. Finally, the bias toward visually brighter items was especially strong when consumers did not have a strong preference for one item over another (i.e., choosing between Snickers and KitKat bars, which consumers stated they like almost equally). The latter two variations of the experiment is highly representative of today’s competitive market place and consumers’ tendency to multitask.

So where does this visual saliency bias come from? The explanation lies in the way that our brain processes information. When making a simple choice, the brain has to process both visual information that allows us to perceive the choice options, and preference information that estimates how much we like these options. The brain must reconcile all these signals (and more: memory, expectations, goals) in order to arrive at a decision. So what this research shows is that sometimes the visual information wins over the preference information – a finding that again shows that choices are driven by many forces aside from actual preference.

So is this visual saliency bias good or bad? More specifically, is it bad for consumers to rely on something as trivial as the brightness of packaging when making a decision? Not necessarily. The visual saliency bias is less likely to occur if you are buying a car or a house, or are engaged in other high-stakes decisions. The bias is more likely to kick in when the decision is less consequential, less costly, you have less time or capacity to fully engage in it, or the options from which you are choosing are liked just the same.

Dr. Milosavljevic and her colleagues showed that when making such simple choices, consumers can spot and choose most of their preferred items in as little as a third of a second. Granted, the visual saliency bias may, in some instances, lead us to make suboptimal choices, but that may be a small price to pay in order to go about our daily lives making rapid, mostly good, decisions. After all, who wants to spend an entire afternoon in front of the store shelf choosing between Snickers and Sour Skittles?

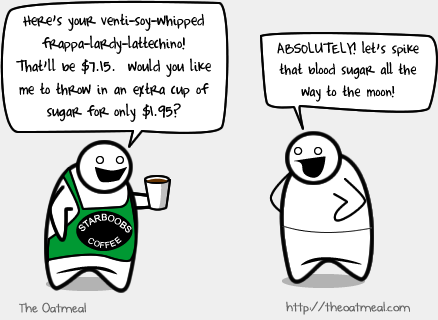

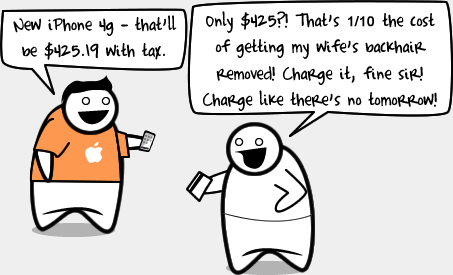

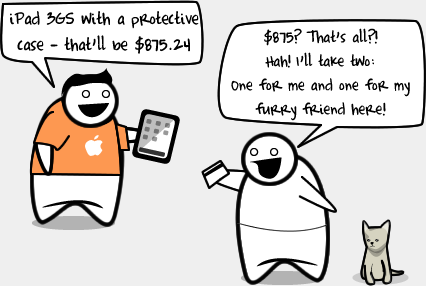

This Is How I Feel About Buying Apps

I came across a funny cartoon the other day that captures an interesting aspect of our purchasing behavior. We are perfectly willing to spend $4 on coffee (for some of us this is a daily purchase), or $500 on devices that you can argue we don’t really need. However, when it comes to buying digital items, such as apps, most of which are priced at $1, we suddenly get really cheap. Why?

http://theoatmeal.com/blog/apps

Here are some reasons. The first is that we are anchored by the price of categories, so when we think about lattes, we compare only across beverages. When we think about apps, we only compare across digital downloads. Thus, when we think about buying a $1 app, it doesn’t occur to us to ask ourselves what the pleasure that we are likely to get from this $1 app — or even what is the relative pleasure that we are likely to get from this app compared with a $4 latte. In our minds, those two decisions are separate.

So now the question becomes, why is the price anchor for apps so low? I think the answer to this is that we have been trained with the expectation that apps should be free. Having lots of free apps on the App Store is clearly advantageous for Apple, because it makes their devices more attractive. However, because FREE! is such a special, exciting price level, it makes the thought of paying even $1 for an app into an agonizing decision.

I think this could have been avoided. Imagine if instead of offering free apps on day one, Apple instead created a really low minimum price–say $0.15. Lots of people would still go for Apps at this price, but instead of being anchored to the idea that apps should be free, we would be anchored to the idea that apps should cost something. Then paying more (maybe even $2) for an app would be a simpler step, maybe one that we could take as easily as paying $4 for a latte.

Can beggars be choosers?

One day a few years ago I passed a street teeming with panhandlers, begging for change. And it made me wonder what causes people to stop for beggars and what causes them to walk on by. So I hung out for a while, engaging in a bit of discreet peoplewatching. Many people passed the beggars without giving anything, but there were a few who stopped. What was it that separated those who paused and gave money from those who didn’t? And what separated the more successful beggars from those who were less successful? Was it something specific about their situation, or their presentation? Was it the beggar’s strategy?

To look into this question, I called on Daniel Berger Jones, an acting student at Boston University who had just finished hiking around Europe. Not having shaved in months and already looking pretty scruffy, he was ready for the job (plus as part of his training to be an actor I figured it would be good for him to learn how to beg for money – at the time he did not see that particular benefit). So I found a street corner and placed him there to take on the panhandling trade. I asked Daniel to try a few different approaches to begging and to keep track of the approaches that made him more or less money. (Of course, after the experiment was over we donated all the money that he made to charity). The general setup was what we call a 2×2 design: When people walked by, Daniel would either be sitting down (the passive approach) or standing up (the active approach) and he would either look them in the eyes or not. So there were times when he was 1) sitting down and looking people in the eyes, 2) sitting down and not looking people in the eyes, 3) standing up and looking people in the eyes, or 4) standing up and not looking people in the eyes.

Daniel got to work, scrounging for money. He stayed on his corner for a while, trying the different approaches. And it turned out that both his position and his eye contact did, in fact, make a difference. He made more money when he was standing and when he looked people in the eyes. It seemed that the most lucrative strategy was to put in more effort, to get people to notice him, and to look them in the eyes so that they could not pretend to not see him.

Interestingly, while the eye contact approach was working in general, it was clear that some of the passersby had a counterstrategy: they were actively shifting their gaze in what seemed to be an attempt to pretend that he wasn’t there. They simply acted as if there was a dark hole in front of them rather than a person, and they were quite successful at averting their gaze.

At some point, something very interesting happened. There was another beggar on the street – a professional beggar – who approached young Daniel and said, “Look kid, you don’t know what you’re doing. Let me teach you.” And so he did. This beggar took our concept of effort and human contact to the next level, walking right up to people and offering his hand up for them to shake. With this dramatic gesture, people had a very hard time refusing him or pretending that they did not seen him. Apparently, the social forces of a handshake are simply too strong and too deeply engrained to resist – and many people gave in and shook his hand. Of course, once they shook his hand, they would also look him in the eyes; the beggar succeeded at breaking the social barrier and was able to get many people to give him money. Once he became a real flesh and blood person with eyes, a smile and needs, people gave in and opened their wallets. When the beggar left his new pupil, he felt so sorry for poor Daniel –and his panhandling ineptitude– that he actually gave him some money. Of course Daniel tried to refuse, but the beggar insisted.

I think there are two main lessons here. The first is to realize how much of our lives are structured by social norms. We do what we think is right, and if someone gives us a hand, there’s a good chance we will shake it, make eye contact, and act very differently than we would otherwise.

The second lesson is to confront the tendency to avert our eyes when we know that someone is in need. We realize that if we face the problem, we’ll feel compelled to do something about it, and so we avoid looking and thereby avoid the temptation to give in and help. We know that if we stop for a beggar on the street, we will have a very hard time refusing his plea for help, so we try hard to ignore the hardship in front of us: we want to see, hear, and speak no evil. And if we can pretend that it isn’t there, we can trick ourselves into believing –at least for that moment– that it doesn’t exist. The good news is that, while it is difficult to stop ignoring the sad things, if we actively chose to pay attention there is a good chance that we will take an action and help a person in need.

Flying Frustrations

A few days ago I woke up at 5:00am to drive to the airport for a trip to Chicago. I got to the airport on time, went through security and arrived at my gate with time to spare. I went through all the motions of boarding the plane, waiting to take off, and finally leaving the ground. As we were in the air, we were informed of inclement weather in Chicago and told that we would have to land somewhere else (South Bend, Indiana). So we were diverted to wait for the weather in Chicago to clear up. When the weather eventually improved, we refueled and finally took off. I missed an important lecture and felt that I had wasted most of my day.

When I think back to my day of traveling, I can’t help but cringe at the thought that my expected two-hour trip took six hours. And even though I have taken many flights longer than six hours in the past without feeling bitter, this experience was particularly annoying for two reasons.

The first reason has to do with the nagging feeling of idleness that I experienced when I was stuck on the plane on the ground, just waiting. And this reminds me of a lesson on the design of air travel: There once was a clever engineer who noticed that the carousels for luggage are spaced at different distances from different gates – some farther and some closer to where the passengers were deplaning. And this engineer redesigned the allocation of carousels such that they minimized the distance to their gate, and therefore minimized the amount of walking that passengers would have to do to pick up their luggage. A few airports implemented this highly efficient system and patted themselves on the back. They were very pleased with their improvement – that is, until people started complaining.

Of course, everything that the engineer predicted was true. By refining the assignment of carousels to match up with their corresponding gates, people had to walk less and could get to their luggage faster. The problem was that this system worked too well, and passengers were beating their luggage to the carousels. When they arrived, they had to twiddle their thumbs while they waited for their luggage to catch up with them.

Think about these two ways to get your luggage: With the original airport design, you walk ten minutes, but when you finally get to the carousel, your baggage gets there a minute after you (taking 11 minutes). In the other, you walk three minutes, but when you arrive you have to wait five minutes for your luggage (taking 8 minutes). The second scenario is faster, but people become more annoyed with the process because they have more idle time. As Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sr. noted, “I never remember feeling tired by work, though idleness exhausts me completely.”

The “good news” is that airports quickly reverted to their former (inefficient) system, and we now walk farther to our suitcases just to avoid the frustrations of idleness.

Now, it’s one thing to waste time, but it’s particularly bothersome when you feel like you are backtracking. In my case of flying to Chicago, the trip took a detour that sent me in away from my final destination. This is the second reason that my flight experience was so irritating — it included an element of backtracking in the opposite direction of my goal.

Let’s think about this idea with another example. Imagine that you are taking the train from point A to point B. You can choose between two paths, both taking four hours but with one key difference: In Trip 1, you take the slow train from point A to B. In Trip 2, you take the fast train, but the train passes B and continues for another hour until it gets to C, and then you change trains and backtrack for an hour to B. It turns out that the second approach is more irritating, even though we should care only about the time and not the direction of progress.

My flight had both of these annoying principles, idleness and backtracking. We wasted lots of time, and we were diverted in the opposite direction. Now, I am positive that this will not be the last time that I experience these travel elements, so the question is how I will deal with these irritations in the future. To overcome the feeling of idleness, I can try finding something to make me feel that the time is spent productively (maybe I should start making lists of things to do and use idle time to manage these lists on my phone). And what about overcoming the annoyance of backtracking? Maybe ignorance really is bliss — and the only solution is not to think about the route that we are taking.

Upside of Irrationality: Chapter 11

Here I discuss Chapter 11 from Upside of Irrationality, Lessons from Our Irrationalities: Why We Need to Test Everything.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like