Ask Ariely: On Technology’s Painless Payment, Email Equilibrium, and TP Tribulations

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Apple recently announced Apple Pay, which will allow iPhone and Apple Watch users to simply wave their gadgets to pay for purchases. How might this technology change our spending habits? Could Apple Pay and other such hassle-free payment mechanisms (such as Amazon’s “1-click ordering”) lead us to spend more—particularly on stuff we don’t need?

—Nikki

The essence of payment is opportunity cost. Every time we face a purchasing decision, we should ask ourselves if getting this one thing is worth giving up the ability to purchase something else, now or in the future.

Different ways of paying make us think differently about those opportunity costs. For example, if we have $20 in cash in our pockets, we will have a hard time not thinking about opportunity cost. If we consider buying a sandwich, we realize that we won’t have money for coffee; if we get a cab, we realize that we won’t have money for dinner. But when we use a credit card or gift certificate, our thinking about opportunity cost will be less natural and prevalent—which means we’re likely to spend more without fully thinking about the consequences.

This is why the general answer to your questions is both yes and no. As you suggest, electronic payment mechanisms can easily lead us to think less about opportunity cost and spend more recklessly. But this doesn’t have to be the case. Electronic payment could be designed in ways that get us to more fully understand our opportunity costs and make more reasonable decisions. Apple Pay and the like could be game-changers, helping us think about our spending much more rigorously than we ever could with cash.

So the questions are: Who is designing these electronic wallets, and for what purpose? Will they be designed to get us to spend more money—or to help us make better decisions? Right now, electronic payments seem to be going down the path of less thinking and more spending—but I hope that at some point, some of the payment companies will change their approach, adopt the perspective of their users and offer electronic payment methods that help us make better financial decisions.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

How can I tell people who email me that I simply don’t have the time to respond to everyone?

—Kat

There is a well-known finding that when you ask couples how much each of them contributes to their relationship, the total far exceeds 100%. That is because we see all the things that we do, small and large, but we fail to see all the things that our partner does. The same is true for the people you respond to. They probably see how busy they are, but they have a hard time understanding the demands on your time.

So why don’t you create an automated email response that lists all the demands on your time, including how little time you have for sleep, exercise and your social life? With this kind of information, I hope, the people you email will understand why you can’t help them.

And while you perfect this approach, make sure you also—nicely—make your significant other aware of all the things you’re doing for the household and the relationship.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Do people use twice as much single-ply toilet paper as double-ply?

—Gary

When toothpaste makers started putting a larger hole in the tube’s cap, people started using more toothpaste. That is because we judge the amount of toothpaste we apply largely by the stretch it covers on the toothbrush, not by its thickness or total volume. I suspect that the same principle is at work with toilet paper, which would mean that we judge the amount of toilet paper by its length—and don’t sufficiently adjust our use to take the added thickness into account.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Staying in School, Balancing School with Family, and Two Things about Consultants

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am a senior in high school, and I really dislike doing homework. We get a lot of it, and it adds nothing to my education. Writing countless essays for English and doing numerous labs for biology isn’t making me smarter, let alone better in those subjects. Here’s my quandary: I know that doing homework is valuable because it assesses how hard I work in school, which is what universities fundamentally look for in applicants—but I feel that if I really want to educate myself, I should dedicate all my free time to gulping down many books on a wide range of subjects. Should I dedicate myself primarily to school and homework, or should I read as much as possible and absorb information primarily through books?

—David

I believe deeply in trying to find things at which we can excel. We can all read poetry, and many of us can probably write bad poetry. But to be really good, to be a poet, you need to devote a lot of time, read widely, work hard, study things from different angles and (ideally) learn from the best. This is what school should give you. Not every teacher and topic is going to be enthralling—but it is still worth it for the teachers and topics that are. My advice: Stay in school, and try to pick a subject or two that excite you enough that one day, you could become the world’s expert on them.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

What advice would you—as a university professor who has been teaching for a long time—give to students who are starting the new academic year?

—Peter

Simple: Keep on investing in your relationships with your family—your parents, of course, but particularly your grandparents.

Here’s why: Most professors discover that family members, particularly grandmothers, tend to pass away just before exams. Deciding to look into this question with academic rigor, Mike Adams, a professor of biology at Eastern Connecticut State University, collected years of data and concluded that grandmothers are 10 times more likely to die before a midterm and 19 times more likely to die before a final exam. Grandmothers of students who aren’t doing so well in class are at even higher risk, and the worst news is for students who are failing: Their grandmothers are 50 times as likely to die as the grandmothers of students who are passing.

The most straightforward explanation for these results? These students share their struggles with their grandmothers, and the poor old ladies prove unable to cope with the difficult news and expire. Based on this sound reasoning, from a public policy perspective, students—particularly indifferent ones—clearly shouldn’t mention the timing of their exams or their academic performance to any relatives. (A less likely interpretation of these results would be that the students are lying, but this is really hard to imagine.)

Kidding aside, social relationships truly are important for our health and happiness, in good times and bad—and fostering them is a wise goal for anyone at any stage of life.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Why do consultants always break problems and solutions into three?

—Alice

When consultants give answers, they often try to strike a delicate balance between making the answer simple (on the one hand) and complete (on the other). I suspect that offering three things to consider strikes this sweet spot.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

The Meaning of Happiness Changes Over Your Lifetime

The following is a scientific and personal article written by CAH member Troy Campbell about happiness.

The following is a scientific and personal article written by CAH member Troy Campbell about happiness.

One lovely afternoon, I began chatting to my grandpa. I was completely unaware he was about to say something that would change my view of happiness forever.

In the middle of our conversation, I felt a lull so I pulled out the classic question. “If you could have dinner with one person, living or dead, who would it be?” I couldn’t wait to talk about my long list of dead presidents, dead Beatles, dead scientists, and a really cute living movie star. But I was also really eager to hear what he’d say.

Then he simply answered, “My wife.”

I immediately assured him it’s not necessary for him to answer like that. We all knew he loves his wife, whom he eats dinner with every night and was currently over in the other room playing cards.

He still insisted, “My wife. I’d have a nice dinner with my wife.”

“Alright,” I said, maybe a little too snappy, “Someone other than your wife.”

“Well okay, it would be my good friend and neighbor, Bill,” He replied.

The I became a little angry and pleaded, “Come on, you wouldn’t pick like John Lennon or Abraham Lincoln or FDR? He was alive when you were, right?”

“No. I’d pick Bill.”

I was just about to explain the point of the game again when it hit me. He already understood the game, and he was not trying to mess with me. What would make him most happy would be to have the same meal he has everyday, with the woman he’s been married to for 50 years.

Happiness to him was ordinary.

***

Over the past years, the interest in happiness has exploded. Everyone seems to want to be happy, read about how to be happy, or listen to Pharrells’ hit song, “Happy.” In response, researchers and gurus have been trying to feed everyone’s interest in happiness by pumping out new studies and New York Times bestsellers.

However, there’s been one factor that’s been missing in all this happiness discussion and in retrospect, it seems ridiculously obvious. That factor is age. As the story of my grandfather vividly displays, at different ages, we are interested in very different kinds of happiness.

Two young psychologists have recently stepped onto the scene and started to explain how happiness varies over the lifetime. Amit Bhattacharjee of Dartmouth University and Cassie Mogilner of the University of Pennsylvania find that the young find happiness and self-definition through extraordinary experiences, like meeting a celebrity. In contrast, older adults find happiness and self-definition through everyday experiences, like dinner with a best friend or wife.

To fully illustrate this concept, consider any family vacation. Think about how difficult it always is to make both the children and parents happy. This is because happiness means something different to younger and older members of the family.

The young crave the extraordinary. They long to bungee jump off a cliff, find a celebrity, and post a stylized Instagram photo that exaggerates the extraordinariness of the moment. Youth culture embraces the concept the of Yolo — “You Only Live Once” — which is just a modern (and arguably more annoying) way to say “carpe diem,” which is just a Latin way to say “seize the day.” Yolo is not something new; it’s just a rebranding of the youth mindset that’s always been around.

In contrast, older people tend to find happiness and define themselves in the ordinary experiences that comprise daily life. So, on vacation, parents often just want to spend time as a family. They want to have a nice family dinner and play card games.

What’s important about Bhattacharjee and Mogilner’s happiness hypothesis is that it is a psychological hypothesis rather than a cultural hypothesis. The scientists argue that with fewer days left in their lives, people start to focus on daily experiences and close-knit friendships. And that’s exactly what the researchers find through a controlled experiment. When they took 20-somethings and made them feel as if their brains would stop optimally functioning at age 40 (as opposed to age 80), the 20-somethings felt like they had less time left and were more interested in everyday happiness activities. They end up acting more like older people.

It’s worth noting that these findings greatly contrast the “Bucket List” hypothesis, the idea that as people feel their days are running out, they are motivated to do the extraordinary. For instance, in the film The Bucket List, two aging men strive to have the most extraordinary experiences possible. Though these cases do exist in society, they may be the exception. In general the rule is that as people feel like they are aging, they turn away from the extraordinary and, like my grandfather, focus on the everyday.

***

So if happiness is as important a goal in life as American culture makes it seem, we need to understand how age affects it. Only then can we know how to better treat our families, communities, and citizens of all ages. Only then will we all be happy, even if happy will mean different things to different people at different stages of their lives.

Fashion and Science – The "Matchy Equation"

Here’s a perfect Friday post for you, featuring science on a lighter topic. Credit to Slate.com and author Alina Simone.

Here’s a perfect Friday post for you, featuring science on a lighter topic. Credit to Slate.com and author Alina Simone.

A woman breezes ahead of you on an airport walkway looking like a page out of Vogue. What is it about her, you wonder as you drag your squeaking roller-bag with a hoodie tied around your waist, that makes her so exquisitely fashionable? The classic cut of her blazer? The Mandarin collar on her silk shirt? That vented trench coat with welt pockets? Well, that certain je ne sais quoi has now been sewed up by science. Specifically:

Fashionableness = -.50m2 + .62m + .49 where m = matching z-score.

Or put another way: Don’t be too matchy-matchy.

That’s the conclusion a team of researchers led by psychologist Kurt Gray arrived at after conducting a pioneering study of the sad question confronting the sartorially challenged each morning: What exactly makes an outfit fashionable? Of course, we perceive clothing as chic for many reasons, not the least of which has to do with whatever Maisie Williams or Ryan Gosling wore to the Best People on Earth Awards. But Gray and his team hypothesized that there must be some pattern underlying our aesthetic preferences.

To read the rest of this article about CAH member Nina Strohminger’s new work click here.

Why People Crave Both Freedom and Constraint

The following is an article Troy Campbell and features research by CAH members, non CAH members, and Troy’s dissertation.

The following is an article Troy Campbell and features research by CAH members, non CAH members, and Troy’s dissertation.

Today, consumers desire to interact rather than to just mindlessly consume. Consumers don’t want to just read; they want to comment. They don’t want to just watch TV; they want to live tweet. They don’t want to just dance at a new club; they want to share the whole night on Instagram.

Consumers want to do more than just “enjoy the moment.” Modern consumers crave what consumer scientists Darren Dahl and Page Moreau call “constrained creativity.” Constrained creativity is defined as an activity with two components. First, the activity has enough freedom for consumers to be creative. Second, and importantly, the activity has enough structure to guide consumers and measure their success, such as through norms or goals.

When we look at what modern consumers love, we readily see these two components. On Twitter, people like the freedom of making original comments but also benefit from the structure of twitter’s enforced length and trending hashtags. With modern expansive video games like BioShock, the freedom is to explore and decide, but within the structure of the game.

Modern technology allows products and experiences to tap into people’s most ancient and basic motives. We love to compete, show off and create. These are basic feelings that even babies and animals crave and enjoy. Modern pleasures like the open world video games and Twitter engage modern consumers in a way that other activities of the past just do not. They provide more than basic entertainment; they provide a semi-structured “game” and an opportunity for self-expression.

Consider even the mundane phenomenon of self-serve frozen yogurt. The reason frozen yogurt has become so popular may not be entirely due to its taste, but to the opportunity for constrained creativity. There is joy in self-serving, there is pride in crafting the perfect swirl and there is self-expression in creating a yogurt that is uniquely personal.

From self-serve frozen yogurt, to Twitter, to video games, entertainment is changing. Whether this change is overall “good” or “bad” for people is an open debate. However, one thing is for certain: This change is powerful enough that if any business cares about obtaining and retaining consumers, they’d better feed people’s craving for constrained creativity. They must understand the modern happiness equation: Happiness = freedom + structure .

Of course, this equation has always been true, but today’s consumers are getting more and more tastes of constrained creativity. With each new bite of a “freedom + structure” activity, consumers develop a new consumption appetite that cannot be satisfied by the entertainment of the past. Today they crave more.

Four Examples of the Freedom + Structure Magic Formula

#1 The IKEA EffectA Harvard University led study finds that when people build or assemble things (like an IKEA bookcase or frozen yogurt), they like the things more because of the effort and self-involvement.

#2 Imagined Involvement The Tonight Show‘s Jimmy Fallon involves TV audience members directly on Twitter through frequent hashtags. Even if most viewers do not tweet, they may imagine what they would tweet and feel a positive sense of imagined involvement.

#3 Instant Feedback Modern technologies provide immediate feedback. If you take a good selfie, you will get likes. If you outsmart a video game boss, you will level up. This tight connection between effort and immediate reward can make technology-based interactive experiences more desirable than real life effort.

#4 Interactive Art Chicago’s famous Bean (also called the “Cloud Gate” by no one but the Wikipedia entry) is an artistic “mirror fun house.” Adding to its popularity its launch coincided with the iPhone launch and the proliferation of the camera phone. The Bean invites visitors to create their own art via creative photography or to just take a very interesting selfie.

The Power of Matching Donations

In a study conducted with Lalin Anik and Dan Ariely of Duke University, social norms were used to incentivize employees to give money to charity. Results were published in the paper Contingent Match Incentives Increase Donations.

In the study, the researchers told a set of contributors to a charitable giving website that their donations would be matched by the charity, but only if a certain percentage of contributors that day either 25, 50, 75, or 100 percent – “upgraded” to a recurring monthly donation. They found that the contributors in the “75 percent” condition contributed at a much higher rate than the other three groups, with as much as a 40 percent increase in committing to recurring donations.

Norton speculates that the higher number is due to a desire to conform to the social norms of other contributors – and not be the cause for the charity to deny matching funds. “No one wants to be the chump that spoils it for everyone else,” Norton says. In other research, that 70-75 percent threshold seems to be the point that has the biggest effect on on behavior – any higher and people may feel like the result is unattainable. The research also shows that the number doesn’t have to correspond to actual rates of participation. Just setting that goal institutes a standard that other people will strive to match.

To read more visit Forbes.com to read Michael Blanding’s article here.

Ask Ariely: On the Bordeaux Battlefield, Irrationality Impact, and Ruminating while Running

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I love eating out, including some wine with dinner—but I can’t tell much difference between different bottles, and I never know which wine to order or how much to spend. When I ask waiters or sommeliers for advice, they often give some flowery descriptions about soil and accents of apricot, but these never help me figure out which wine pairs best with my meal. The whole wine-ordering business makes me feel incompetent and inadequate. Do you have any simple advice for how to order wine?

—Josh

The first thing to realize when picking from a wine list is that you are in a battlefield. This is a battle for your wallet—a fight between the restaurant, whose interest is to get as much of your money as possible right now, and your savings account. The restaurant’s owners have much more data than you do about how people make their wine decisions, and they also get to set up the menu in a way that gives them the upper hand.

In particular, restaurants know that people make relative decisions: If a place includes some very expensive wines on its list (say, bottles for $200 or more), customers are unlikely to order them, but their mere presence on the list will make a $70 bottle seem much more reasonable.

Restaurants also know that many of us are cheap—but we don’t want to seem cheap, which means that almost no one orders the cheapest wine on the menu. The wine of choice for cheapskates is the second-cheapest wine on the list.

Finally, the restaurants have another weapon in their arsenal: waiters and sommeliers who add to our feelings of inadequacy and confusion and, in the haze of our decision-making, can easily push us toward more expensive wines.

Now that you are starting to think about ordering wine as a battle, or maybe a game of chess, you can think ahead. Perhaps decide in advance to spend up to a certain amount of money on wine. Or tell the waiter that you have a religious rule against spending more than a set sum on wine and ask for a recommendation that would fit within your boundaries.

And if you really want to strike back, inform the waiter that you have allocated a total of $50 for the tip and wine combined—so the more you spend on wine, the less you will leave for a tip. Now let’s see what they recommend.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am convinced that some of our decisions are irrational, but what’s the proportion of irrational decisions?

—Julianne

The right question, I think, isn’t the proportion of irrational decisions but their impact. Think about something like texting and driving—perhaps you do it only 3% of the time, but each of these instances could kill you and other people. So what we really need to ask ourselves isn’t the proportion of our irrational behavior but the extent to which such behavior can harm our lives, the lives of those around us and society in general.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I often hear people say that after they go for a run, their minds are clear, and they can focus better on big questions at work. Can this be so? Do we need to exercise to think clearly?

—Sam

I suspect that running isn’t the best way to clear the mind. In fact, I suspect that running while thinking about work is a recipe for designing products and experiences that enhance agony and misery. Now that I think about it, maybe this was the start of what we know as “customer service” for cable companies.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Reservation Reservations and the Psychology of Parking

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

—Roger

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

—Ian

______________________________________________________

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Why you should watch football until the very end

By Wendy De La Rosa, Dan Ariely, and Kristen Berman

During the last month, the World Cup has captivated the globe, including our team at Irrational Labs. We have watched all 64 games and rejoiced / suffered through each of the 171 goals (not counting penalty kicks). This 2014 FIFA World Cup turned out to be an entrancing tournament: Eight of the “Round of 16” matches went into overtime, four went to penalty kicks, and the final match ended with Germany scoring in the 113th minute!

When we watched the now infamous Germany – Brazil game, we couldn’t help but come up with some interesting behavioral questions. When German midfielder Thomas Mueller scored the first goal against Brazil 11 minutes into the game, many of our Brazilian friends said this is just the start of the game.

And while we all know what happened, we started thinking: Were our Brazilian friends onto something – are there more or less goals and attempts late in the game?

One would stipulate that there is no difference in scoring between the first and the second half. Every goal matters equally, regardless of when it is scored, and players should attempt to score with the same amount of effort and success over time.

Another hypothesis is that fewer goals are scored in the second half as players fatigue Unlike basketball, where players are often substituted in and out, most of the football players are on the field for the full 90 minutes of play (sometimes 120 minutes if it goes to overtime).

Yet another hypothesis is that players score more goals in the second half as they are closer to the end of the game. Motivation research suggests that agents are more motivated as they near the end of their stated objective, whether a marathon or a life altering championship.

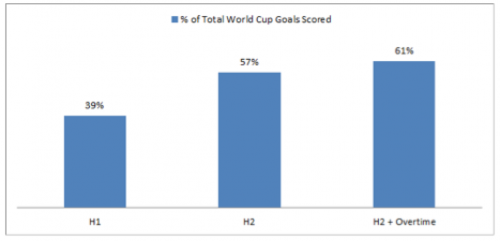

It turns out our Brazilian friends were right; more goals are scored in the second half! Of the 171 goals scored in the World Cup, 39% of the goals were scored in the first half, 57% in the second half, and 61% in the second half when we include overtime.

After learning that players score more goals in the second half, we wanted to know why. There are two ways to increase goals scored: increase attempts or increase skill (measured as goals / attempts). Which one is at play here?

The skill hypothesis stipulates that players are “super humans” who perform best when they are under pressure. Consider German Mario Gotza, a substitute midfielder, scoring the game winning goal against Argentina just seven minutes before the end of the match.

To answer this question, we compared a team’s skill in the entire game to a team’s skill in the last 15 minutes of a game. Our analysis showed that there is no statistical difference in skill when you compare these 15 minutes. This is consistent with an interesting study done by Dan Ariely and Racheli Barkan, where they studied the shooting percentages of “clutch players.” Clutch players are NBA players who are widely regarded as “basketball heroes who sink a basket just as the buzzer sounds.” As it turns out, clutch players do not become better basketball players as the pressure increases in the last few minutes of critical games. Basketball players, like our football players, do not increase in skill towards the end of the game.

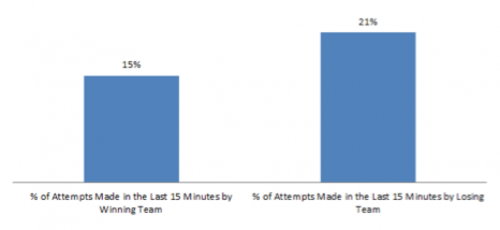

So if it’s not a question of increased skill (% conversion), it must be a question of effort (number of attempts). Given this finding, we decided to analyze the number of attempts made by players, and whether they increase as the game wears on. Which team is attempting the most goals at the end of the game? One hypothesis is that the leading team increases their attempts as they are more confident and have strong momentum behind them. The other hypothesis is that the trailing team would attempt more goals at the end of the game because the cost of losing is more salient to them.

We can see loss aversion playing out in golf green. According to researchers, Devin Pope and Maurice Schweitzer, “Golf provides a natural setting to test for loss aversion because golfers are rewarded for the total number of strokes they take during a tournament, yet each individual hole has a salient reference point: par (the typical number of shots professional golfers take to complete a hole).” After analyzing PGA Tour putts (the last shot before a hole), they noticed that golfers are extremely loss averse. Golfers make putts for birdie (one shot less than par) significantly less often than identical-length putts for par (getting to par). The researchers estimate that this loss aversion costs the average pro golfer about one stroke per 72-hole tournament, and the top 20 golfers about $1.2 million in prize money a year.

Does this theory hold true in football? After analyzing the data, we found that during the last 15 minutes of each game, number of attempts made by the trailing team (as a percentage of their total attempts made during the game) increase, while the number of attempts made by the winning team decreases.

Why is this? We believe we can explain this phenomenon with loss aversion. Loss aversion is the behavioral economic concept that states that we value losses more than we value commensurate gains. The other stipulation in loss aversion theory states that we are risk seeking in losses and risk averse in gains. In other words, our risk appetite increases when we are losing. This phenomenon is known as “risk shift.”

The feeling of loss aversion is heightened in football. Think about the cost of a goal in football compared to the cost of a basket in basketball. Because goals are so difficult to make, the cost of giving up a goal is greater than the cost of not making a goal. Thus, teams are naturally more defensive, focused on avoiding “a goal” or a “loss” much less than “scoring” or “gaining” for most of the game.

Loss aversion is a powerful concept, and we are all susceptible; even world class football players. So to go back to our Brazilian fans, expecting more effort as the game continues is a reasonable expectation. Unfortunately, and as the Brazilian fans found out, sometimes effort is not enough.

Sports and Loss Aversion

I got this question about the World Cup and I can’t put it in my WSJ column, but I still think it is worth while answering, and particularly today.

Dear Dan,

You have mentioned many times the principle of loss aversion, where the pain of losing is much higher than the joy of winning. The recent world cup was most likely the largest spectator event in the history of the world, and fans from across the globe were clearly very involved in who would win. If indeed, as suggested by loss aversion, people suffer from losing more than they enjoy winning — why would anyone become a fan of a team? After all, as fans they have about equal chance of losing (which you claim is very painful) and for winning (which you claim does not provide the same extreme emotional impact) – so in total across many game the outcome is not a good deal. Am I missing something in my application of loss aversion? Is loss aversion not relevant to sports?

Fernando

Your description of the problem implies that people have a choice in the matter, and that they carefully consider the benefits vs the costs of becoming a fan of a particular team. Personally, I suspect that the choice of what team to root for is closer to religious convictions than to rational choice — which means that people don’t really make an active choice of what team to root for (at least not a deliberate informed one), and that they are “given” their team-affiliation by their surroundings, family and friends.

Another assumption that is implied in your question is that when people approach the choice of a team, that they consider the possible negative effects of losing relative to the emotional boost of winning. The problem with this part of your argument is that predicting our emotional reactions to losses is something we are not very good at, which means that we are not very likely to accurately take into account the full effect of loss aversion when we make choices.

In your question you also raised the possibility that loss aversion might not apply to sporting events. This is a very interesting possibility, and I would like to speculate why you are (partially) correct. Sporting events are not just about the outcome, and if anything, they are more about the ways in which we experience the games as they unfold over time (yes, even the 7-1 Germany vs Brazil game). Unlike monetary gambles, games take some time, and the time of the game itself is arguably what provide the largest part of the enjoyment. To illustrate this consider two individuals N (Not-caring) and F (Fan). What loss aversion implies is that N will end up with a neutral feeling with any outcome of the game, while F has about equal chance of being somewhat happy or very upset (and the expected value of these two potential outcomes is negative). But, this part of the analysis is taking into account only the outcome of the game. What about the enjoyment during the game itself? Here N is not going to get much emotional value watching the game (by definition he doesn’t care much, and he might even check his phone during the game or flip channels). F on the other hand is going to experience a lot of ups and downs and be emotionally engrossed and invested throughout the game. Now, if we take both the process of the game and the final outcome into account — we could argue that the serious fans are risking a large and painful disappointment at the end of each game, but that they are doing it for the benefit of extracting more enjoyment from the game itself — and this is likely to be a very wise tradeoff that maximizes their overall well-being.

This analysis by the way has another interesting implication — it suggests that the value of being die hard fans is higher for games that take more time, where the fans get to enjoy the process for longer. Maybe this is why so many sports take breaks for time outs and advertisements breaks — they are not only doing it to increase their revenues, but they are also trying to give us, the fans, more time to enjoy the whole experience.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like