Ask Ariely: On Valentine’s Day, (Over)valuing our Things, and Parental Approval

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My friends and I hate Valentine’s Day: It feels arbitrary, contrived and commercial. How can we change our attitude to make the day feel meaningful?

—Frank

What bothers you may not be the arbitrary nature of Valentine’s Day. Lots of celebrations occur on arbitrary dates (New Year’s Day, Thanksgiving and so on), and few people complain. What probably bugs you is the feeling that Valentine’s Day was created as a ploy by the marketing departments of jewelry, chocolate and flower sellers. And it is this adversarial perspective that makes you dislike Valentine’s Day.

Let me suggest a different way to frame Valentine’s Day. In my experience, the vast majority of people aren’t romantic enough, and we often take our significant others for granted. This lack of attention and care translates to conflicts and joint misery. Basically, when we are left to our own devices, we just don’t do enough—as the noted behavioral economist Stevie Wonder put it—to say how much we care.

So since we seem to be romantically challenged, we probably could use some reminders and rules to spur more affectionate behavior. So think of Valentine’s Day as an annual mechanism to help us reflect on our loved ones and pay them a bit of extra attention. The only real question is: Why do we have Valentine’s Day only once a year? Don’t we need it once a week, or at least once a month?

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My job involves helping divorcing couples divide their marital estates—their income, assets and debt. I’ve often noticed that my clients irrationally overvalue what they personally own—from jewelry and furniture to pension plans. How can I get them to think more logically about their property?

—Adam

Sometime I ask the students in my classes to build a simple Lego car. When they finish, I place a large trash bin in the middle of the room and ask them to break their creation apart and deposit the pieces in the bin. I also tell them that I will be taking all the pieces, sorting them into sets and using them again in next year’s class. Each time, I see horror in their faces. What kind of a person would ask them to take their creation, destroy it and give it away?

I let them marinate in their grief for a few seconds as I head to the back of the room to haul in the trash can. Before anyone starts breaking their Lego creations, I stop them, tell them that they can keep their Legos and ask them to reflect on their feelings. The students had only a very brief relationship with their Lego masterpieces, but they got very attached to it—which demonstrates how quickly we get attached to the things we own. Now, imagine how much more attached people get if they own something for a really long time.

So what can you do about this attachment problem in your business? Try taking both parties’ possessions and moving them to a trust for a year. When you back come to distribute the property a year later, they may well feel less ownership—and be more open to a reasonable division.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I don’t know how to tell whether I am in love. Each time I become close to a boy, I start thinking about whether my family would accept him and start seeing him through my parents’ eyes. So I never fully immerse myself in any relationship, and I can’t disentangle my opinion of the guy from my parents’. How can I figure out my own, independent feelings?

—Seema

A hint: If you’re thinking about your parents when you meet a boy, you aren’t in love.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Why Super Bowl Commercials Are So Much Better

On Sunday, the Super Bowl once again served up a batch of funny, cool, and even moving commercials. For decades now, Super Bowl commercials have continued to impress and touch us with a car starting Darth Vader kid, a horse-befriending dog, a 1984 rule breaking Apple user, a Pepsi drinking Cindy Crawford, and on and on.

On Sunday, the Super Bowl once again served up a batch of funny, cool, and even moving commercials. For decades now, Super Bowl commercials have continued to impress and touch us with a car starting Darth Vader kid, a horse-befriending dog, a 1984 rule breaking Apple user, a Pepsi drinking Cindy Crawford, and on and on.

This has left many wondering: why aren’t all commercials as good as the Super Bowl commercials? If business can make such great ads, why don’t they always do so?

To answer these questions, we need to remember the real purpose of any advertisement is: to be effective. Unfortunately for viewers, ads don’t need to be good to to be effective.

The Super Bowl is a rare case where the audience is paying full attention expecting greatness. This environment allows the ads to be complex, nuanced, and entertaining.

However, outside the Super Bowl, ads have to play an entirely different game. Many everyday-ads have to fight to win the attention of highly distracted TV viewers, who are often channel surfing or multitasking. Many viewers don’t even look at the screen as they play on their computers, clean, or get ready for work.

This means the ads cannot tell an extended story about a puppy returning home like the #BestBuds Budweiser ad from this year. These ads only work during times like the Super Bowl when people say, “Be quiet the commercials are on!”

Instead, everyday ads must be loud, aggressive, and full of brand references. They must grab viewers’ attention and increase awareness.

Businesses want their products to enter into what market researchers call consumers’ “consideration set,” – the few products that come to mind when consumers thinks about a product category. This is often accomplished through annoying ads or unconscious mental processes, and can come at the expense of quality.

This means ads like Coke’s 2015 Super Bowl spot #MakeItHappy, though cool or even inspiring, do not work well during the average commercial break. For instance this 2015 Coke ad features a somewhat complex premise with multiple lines of evolving text that require reading. And there’s no helpful guiding narration. The result: it is a super engaging ad, but only for viewers who are already engaged. This advertisement would not stand a chance during a Good Morning America commercial break, while a parent focuses primarily on prepping a child’s lunch.

Finally, most normal ads get heavy rotation. This means the ads need to be effective over relentless viewings. Many Super Bowl ads rely on a twist, shock factor, or a heartfelt narrative. Excessive viewings of these types of ads can lead to a loss of value and could even cause backfire effects.

For instance, the “edgy” 1984 Apple ad could lose its edge with each viewing. One can think of a Super Bowl ad like an amazing artsy song—great, but not for every moment—and everyday ads like the second radio single from any Maroon 5 album—mundane but infinitely digestible.

The Bigger Lesson

When we contrast Super Bowl ads with normal ads, we learn a powerful business lesson: being effective does not always mean being good. It’s a lesson many of us find hard to swallow, but it’s a bitter pill we all need to take.

Quality has its place in TV advertising and so too does effective mediocrity. Unfortunately, the latter is usually the norm. Yet, we can all be thankful that for one evening each winter, the stars align such that what makes an advertisement effective is also what makes it enjoyable.

By Troy Campbell

@TroyHCampbell studies marketing as it relates to identity, beliefs, and enjoyment here at the Center for Advanced Hindsight and the Duke University Fuqua School of Business. In Fall 2015 he will begin as an assistant professor at the University of Oregon Lundquist College of Business.

Ask Ariely: On Putting off Procrastination, Selling Sherlock, and Feeling the DICE

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

______________________________________________________

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Honoring Housework, BE to Business, and Laundering Linens

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Many women don’t feel recognized for all the work they do at home. When their husbands come home late from the office to something other than total bedlam, the oblivious men often fail to provide any appreciation or recognition. Would it help if women got paid for their housework? And if so, what is the best way to set up those payments?

—Lisa

I can’t think of any context in which one partner in a family should directly pay the other. But we do need to make sure that earning inequality doesn’t turn into power inequality.

One of the best (and worst) things about money is that it is easy to measure. So each partner’s financial contributions to the household are very clear, and differences can be overemphasized.

Consider a couple in which Person A earns much more than Person B, but Person B does everything else for the household. In such a case, A’s contribution to the relationship is easily quantified (bringing home most of the bacon), whereas B’s bit (taking care of the house, raising the children, dealing with paperwork, bills and so on) can’t be measured as precisely.

If the couple focuses on what’s easy to measure, A’s contribution looks more central. So A could feel more deserving, entitled and commanding while contributing less overall.

There is no magical solution to this problem, but one good step is to deal directly with the flow of money. Start by having one joint checking account for all income and ongoing expenses. On top of that, open two separate savings accounts (one for each partner), and split all savings equally into them.

Legally speaking, this type of accounting doesn’t make any difference, but in psychological terms, it makes a key statement about equality in financial contributions. It could weaken the link between financial contribution and power and offer a more holistic view of contributions to family life.

______________________________________________________

What can businesses learn from your academic field of behavioral economics?

—Bella

As with any other scientific endeavor, my field has reached, over time, a better understanding of its domain—human behavior. The process has been slow, but the lessons are accumulating.

We have found, for example, the principle of loss aversion: It turns out that we humans hate losing more than we enjoy gaining. Or the IKEA effect—the finding that, once we take part in making something (like IKEA furniture), we start really liking it, and we assume that other people will like our creation too. These are discoveries that businesses can use in developing their products and services.

For all that we’ve learned, however, I suspect that the most important lesson is how little we know—the lesson of humility. We understand a great deal about human behavior, but we also have a lot of gaps, assumptions and blind spots. By training, social scientists are happy to admit how little we really know and much room there is for improvement.

If businesses adopted this approach, trusting their intuitions less and relying on research more, they would get a very high return on investment. Admitting our shortcomings is an important first step.

______________________________________________________

We host a lot of overnight guests. Should I change the sheets on the guest bed every time a new guest arrives, even if the last one only stayed with us for one night? —Debbie

I am sure that you don’t want to tell your new guests that they are using “only slightly used linens,” and I am almost sure that you don’t want to hide things from your guests—so yes, change the sheets every time.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Guilt-Free Gift Cards, Business Buddies, and Fading Favors

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

This holiday season had me wondering: Why do people prefer to give and receive gift cards rather than cash, which you can use anywhere for anything?

—Van

Gift cards limit the way we can use money, which means that, from a strictly rational viewpoint, they are inferior to cash. But people prefer gift cards because of an irrational emotion called guilt—or, more accurately, because of our need to alleviate guilt.

When we look around us, we feel guilt over our desire for many different things: fancy chocolates, pens, expensive headsets, electronic gadgets, etc. We want these things, but the guilt caused by our wants is powerful, so it sometimes stops us.

When we get money, we’re likely to feel guilty about spending it on our more self-indulgent desires. But when we get a gift card, the guilt is much reduced and sometimes eliminated.

Interestingly, the particular level of guilt alleviation depends on the type of gift card. For example, if the card is an American Express gift card, it is basically the same thing as money, and it doesn’t ease much guilt. But if the gift card is restricted to Tiffany’s or REI, that money suddenly becomes more valuable. A dollar without guilt is worth more than a regular dollar.

And if you got any gift cards this holiday season, of any type, I suggest using them as if they were meant to be spent only in your favorite store—and enjoy them guilt-free.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I realize that mixing friendship and business isn’t always the best idea, but I’m starting a business with a friend anyway, and I want to know the best way to mix the monetary bits of the business with the social aspects. Is there a single recipe for this?

—Clara

Going into business with people we know and love is indeed tempting. So long as the venture is going well, working with friends and family can be great: The extra trust and commitment that everyone shares can help both the business side and the social relationship.

The problem is that things frequently go awry. Then the damage done is often not just the professional downside plus the social downside; it can be the professional downside multiplied by the social downside.

So I would prepare yourselves by outsourcing any disagreements. Decide upfront that every time you disagree, even on something small, you will both go to somebody external who isn’t personally involved. Each of you will then describe your side of the argument in five minutes or less and let that person decide for you—and no matter what, you will take their advice and never mention the topic again. This way, you not only have a mechanism for resolving disagreements, but you can do so quickly, before any tension can build up and destroy either your friendship or business.

One more thing: Pick a third party whom you both dislike. Some intriguing research shows that when an arbitrator is nasty, both parties feel more camaraderie, work better together to resolve the issue and, of course, want to end the disagreement as soon as possible.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

A while back, a friend did me a favor with the understanding that I would “return the favor” later. At first, I was eager to reciprocate, but after several months, I’ve become less aggressive about offering to find a way to help her out. Do favors have a shelf life?

—Jen

Only in the minds of the people who owe them.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

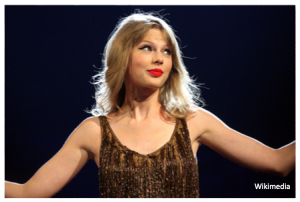

2014 In Review: The Psychology Behind Protests, Ice Buckets, Taylor Swift, and More

From the silly to the serious, Troy Campbell, a Ph.D candidate at the center, explains the psychology behind five highlights of 2014 in no particular order.

#1

The Birth of Modern Charity

It dominated Facebook feeds for weeks—everyone from your high school girlfriend to your college roommate to your extended family seemed to join in. The trend swept the nation, yet the question remains: why was the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge so successful?

The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge shows that with successful charity more than just altruism is involved. Social pressure to donate can be extremely motivating and so can self-serving desires to seem clever, cool, or in some cases even sexy on social media.

This viral phenomenon vividly demonstrated how most charities succeed: through a cocktail of altruism, social pressure, and selfishness. Anonymous donors, donors induced by guilt, and donors wooed by the promise of having their name prominently display on a wall have always existed. For the social media inclined, some donors may be tempted to donate or promote in order to have their face posted on Facebook.

So how should we react to the Ice Bucket Challenge’s success? With praise or backlash?

It’s definitely true that the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge was imperfect, as some people did the challenge for the “wrong reasons,” donated disproportionately to one charity, or simply could have given more. But far too often, we let perfect be the enemy of the good (especially when it comes to charity). Moreover, we often expect charity drives to be perfect when humans, as psychological research has consistently demonstrated, are so far from perfect.

As flawed as this phenomenon was, anyone interested in charity or human behavior would be remiss to ignore the lessons the Ice Bucket Challenge has taught us about how to create a viral and powerful, albeit imperfect, charity movement when donors will always be part altruistic givers, part herd-followers, and part narcissists.

#2

The Year of “Happy”

Pharrell’s summer hit, “Happy,” was the number one song on Spotify this year, and it certainly seems that Americans have started to care more and more about becoming happier.

Pharrell’s summer hit, “Happy,” was the number one song on Spotify this year, and it certainly seems that Americans have started to care more and more about becoming happier.

There were three widely popularized and reported scientific findings this year that helped us understand how to be as happy as Pharrell’s song.

I – Experiences. The mantra of happiness research this year was: If you want to be happy, you shouldn’t spend money on material goods and yourself, but rather, you should spend money on experiences and on those around you. Amit Kumar and others have demonstrated that experiential purchases versus material purchases provide us with more anticipated happiness, higher long term happiness, and better social connections. My own lab mate Lalin Anik, has shown that giving to others not only improves happiness, but also boosts productivity. As recent research has demonstrated, it truly is better to give than to receive.

II – Meaning. Modern research has gone beyond feelings like pleasure or enjoyment to explore deeper issues like finding meaning in life, a sense of purpose, and the values we hold. For instance, having children can be a source of incredible stress, but it has also been shown to make adult life more meaningful. A number of scientific papers this year explored how obtaining happiness and obtaining meaning can sometimes require slightly different paths.

III – Differences. It’s important to remember that what makes you happy does not always make others happy too, something Ed O’Brien, myself, and our colleagues found this year that often people don’t realize. The science community this year poured out examples of how differences vary across people. One vivid example of this came from Amit Bhattacharjee and Cassie Mogilner, who found that younger and older adults crave different types of happiness. Younger adults crave spectacular moments of happiness (e.g. meeting a favorite celebrity) and older adults crave more mundane everyday happiness (e.g. relaxing with relatives). I recently wrote about how I learned this first hand, when my grandpa sweetly explained to me how just mudanely being with his wife made him happier than anything.

#3

The Desire For Authenticity

Today, people want natural ingredients in all aspects of their lives. People want it in their foods, their local products, and even in their favorite televisions shows. Well-developed characters, flaws and all, are becoming a trademark of primetime cable television. We need look no further than the spectacular success of the drama Breaking Bad or new age sitcoms like Louis CK’s Louie and Lena Dunham’s Girls. These shows demonstrate that there is a new currency of authentic self-expression and honest presentations of one’s flaws. From food to entertainment to beauty there’s a real big push to “be real.”

Today, people want natural ingredients in all aspects of their lives. People want it in their foods, their local products, and even in their favorite televisions shows. Well-developed characters, flaws and all, are becoming a trademark of primetime cable television. We need look no further than the spectacular success of the drama Breaking Bad or new age sitcoms like Louis CK’s Louie and Lena Dunham’s Girls. These shows demonstrate that there is a new currency of authentic self-expression and honest presentations of one’s flaws. From food to entertainment to beauty there’s a real big push to “be real.”

At psychology conferences, you can already see authenticity is going to be one of the next big topics in consumer science and is going to prove to be a complicated one. For instance, new research looks at how the desire for “authenticity” can lead to some nasty results, like the exclusion of others. Today, many groups have become quite hostile to people who are not “authentic.” Some controversies like #GamerGate and handwringing about “fake gamer girls” shows one of the perils of the pursuit of authenticity when combined with ugly cultural prejudices.

#4

The Album You Had to Buy

When Taylor Swift removed her music from Spotify, the world responded by purchasing her new album, 1989, en masse. It’s interesting to wonder, though, whether the people who actually bought her album ended up liking it more or less than if they had just streamed it? The answer according to psychological science is almost certainly “yes.”

When Taylor Swift removed her music from Spotify, the world responded by purchasing her new album, 1989, en masse. It’s interesting to wonder, though, whether the people who actually bought her album ended up liking it more or less than if they had just streamed it? The answer according to psychological science is almost certainly “yes.”

When people buy things, they experience those products differently due to a process called “effort justification.” People like products and care for them more when they put more effort or money into them.

Taylor Swift also made her album a quasi-symbol of social status, since it became more difficult to acquire. Owning and being able to talk about such a culturally relevant album required actually purchasing it. This way, owners of the album came to feel more like devoted fans or the culturally savvy, since the uninitiated can’t listen for free. As research from this center has previously shown, this feeling of exclusivity and mastery changes (and improves) one’s relationship with the product.

#5

The Role of Science and Protests

For a long-time now, social scientists have shown there are still damaging systematic racial biases at work in America. The protests that marked the end of 2014 have shown the powers and limitations of social science’s ability to create positive social change.

For a long-time now, social scientists have shown there are still damaging systematic racial biases at work in America. The protests that marked the end of 2014 have shown the powers and limitations of social science’s ability to create positive social change.

Social science can be powerful. For instance with the existing social science data, we were able to answer questions like, “Are there racial biases in people’s minds that support the notion that people in power treat people of different races differently?” The unambiguous answer to this question is “yes.” So even if there was ambiguity about the role of race in some of the powder keg incidents behind the protests over the topic of race, the larger data does support the need for systematic changes that address race.

But the protests have also shown the limitations of social science. Science alone rarely leads us to social change. Good science must also be paired with promotion, education, and wide spread communication. Additionally, it depends on social action and the attitudes of the broader culture. It’s not always easy to get people to believe science when the results are inconvenient or cause “solutions aversion.”

#6 (Bonus)

The Problem of Solution Aversion

This year was full of “solution aversion,” a term my colleague, Aaron Kay, and I coined to describe the act of denying a problem when one doesn’t like the solutions. This research received an abnormal level of media buzz, reaching the top of popular news aggregators like Reddit, we think because it neatly and clearly encapsulates the biases in politics that frustrate so many of us these days.

This year was full of “solution aversion,” a term my colleague, Aaron Kay, and I coined to describe the act of denying a problem when one doesn’t like the solutions. This research received an abnormal level of media buzz, reaching the top of popular news aggregators like Reddit, we think because it neatly and clearly encapsulates the biases in politics that frustrate so many of us these days.

Particularly, we find that when solutions to problems conflict with people’s political ideologies, people are more likely to deny the problems exist and the scientific evidence behind the problems. One example we used was the problem of climate change. We found experimentally that the more people dislike the proposed political solutions to climate problems, the more likely they were to deny the existence of the climate change problem.

These findings also received and gained a life of their own via blogger-commenters who used our political findings to highlight how solution aversion can also generally be problematic in today’s personal decisions. For marital, health, and career problems, many pointed out the aversive solutions like therapy and dieting can start to warp views about the actual existence of problems.

I now have pages and pages of potential processes of solution aversion to motivate future research. Medical doctors commented about their patients’ solution aversions, business professionals about their own and their employees’ solution aversions, and political persons about different groups’ solution aversions. The comments went on and on. It’s times like these you remember that certain pockets of the Internet can be truly awesome.

Looking Back and Looking Forward

If you have any thoughts on the psychology of 2014 or the future psychology of 2015, let us know. I believe in the promise of crowd sourcing the scientific enterprise and thought whenever possible.

Here’s to a happy, more rational, and more psychologically sound New Year.

The Psychology of a California Christmas

Our local California native Troy Campbell discusses the reason, rational or not, Californians come to love their sunny type of holidays.

Our local California native Troy Campbell discusses the reason, rational or not, Californians come to love their sunny type of holidays.

As a Southern Californian native, nonnatives always assume I must be sad every time Christmas rolls around and it’s not white. They tell me that I must feel blue because something “essentially Christmas” or “properly winter” is missing.

Yet, nothing could be further from the truth. While the world assumes Californians are sad on Christmas day, many Californians are actually quite happy as we stroll along the beach and enjoy the unique concept of a Southern California Christmas.

As the Southern Californian band Jack’s Mannequin sings: “It’s Christmas in California and it’s hard to ignore that it feels like summer all the time, but I’ll take a West Coast Winter … It’s good to be alive.”

If you moved here you would probably hate this “always summer” vibe. You would probably miss the snow and the cold. But we don’t. We don’t dwell on how we are missing out on the typical winter traditions, because winter does not mean the same things to us that it does to you.

For us, winter means putting on a long-sleeve T-shirt and sharing a peppermint flavored frozen yogurt on a sunny patio; or taking a late-night walk on a decorated pier, possibly after a Christmas Eve service with the people we love; or strolling down Disneyland’s Main Street under the artificial (but quite awesome) snow. Experiences gain value through memories and localized meanings not just global meanings.

If Southern Californians wanted to, we could drive inland and be in the snow in a few hours or less and enjoy the global stereotypes of Christmas. But we don’t all migrate inland for the winter. Why? Because that’s not who we are and that’s not what winter or Christmas means to us.

In the winter season, many Californians often even develop what social scientists call an “oppositional identity.” We choose to swim or surf on Christmas Day and we proudly (and sometimes annoyingly) post photos of how beautiful and completely unmiserable it truly is here. In Southern California and the West Coast at large, we develop traditions in opposition to traditional winter norms.

In general, the world is often jealous of our generally perfect weather. So it is understandable that the world would like to think that for one season or just one Christmas Day, Southern Californians are jealous of others’ weather. But the truth is, were are not jealous. Maybe we’re missing something. Maybe we should be jealous of those enjoying a White Christmas. But because of who we are and the way we have grown up, we will never be convinced that anything is missing from our West Coast Winter.

When West Coasters are on the beach, with a new pair of Rainbow sandals fresh from the San Clemente outlet, a board in their hand, and In-N-Out Burger in their other hand, watching a pelican fly over the Christmas lights on the pier, it doesn’t feel like the moment is missing anything! In fact, for a Southern Californian native, a moment like this could not feel any more complete.

So let me wish everyone everywhere a happy holidays, whether you are somewhere as beautiful as California or as miserable as where you are. Sorry, couldn’t resist. But it is likely that wherever you are, you’ve come to love your type of Christmas or holidays. It’s just how the mind works, and whether that is irrational or not, it is in this case quite fantastic for us all.

By Troy Campbell

Ask Ariely: On Selfies, Saving Strategies, and the Scarcity of Attractive Males

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve noticed more people taking selfies. Some are even walking around with specially designed phone holders that help position their phones a bit farther away for taking better selfies. I’m not part of this selfie age group, and I find it all odd and somewhat annoying. Can you help me understand the fascination? Why can’t the new generation take pictures the good old way?

—Ayelet

The selfies phenomenon is complex, but here are some highlights: Its starting point is those moments we want to capture, for our own memories or to share with others. Now, if we were to stop what we’re doing and ask a stranger to take our picture, we would be stepping out of the moment emotionally: We’d have to stand still while smiling artificially, wait for the picture to be snapped, then try to get back to whatever were doing and feeling.

Selfies solve this problem because we don’t step out of the moment. A selfie can even enhance the moment by getting us to stand closer to one another and look at ourselves together on-screen—a sort of celebration of the shared experience.

Another interesting thing about selfies: We always expect them to produce an awkward, low-quality picture. So those of us who always worry about how we look on camera don’t need to fret as much: Everyone looks bad.

Finally, there is an important interplay between language and decision making at work here: Once we gave a name to the activity of huddling together, looking up at a phone from an uncomfortable angle and taking a picture, it became socially acceptable.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Setting up automatic retirement savings mechanisms (where the default is participation but people can opt out) has been shown to increase savings rates in wealthy countries such as the U.S., Denmark and the Netherlands. But what can be done to raise savings rates in developing countries, where many people work in the informal economy, don’t get regular paychecks and lack access to sophisticated banking services?

—Varun

A recent World Bank report offers some hope. In Kenya, according to the bank, many households report that a lack of cash often holds them back from investing in preventive health products such as insecticide-treated mosquito nets. To help Kenyans save for such needs, researchers provided families with a lockable metal box, a padlock and a place to write the name of the desired item. Simply by making these boxes available, researchers increased the purchase rates of these preventive health products by 66% to 75%, the report said.

The idea behind this approach is that people tend to allocate their funds through a process of “mental accounting” in which they define categories of spending and structure their outlays accordingly. The metal box, the lock and the label all helped people to put money in a separate account dedicated to preventive health products.

More generally, this is an example of the value of labeling for saving and spending—something that each of us can probably use when salting money away for vacations or a rainy-day fund and when grappling with how much to spend on groceries, going out and home renovations.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Broadly speaking, does the advantage of attractiveness differ across gender? Is it better to be attractive as a woman or as a man?

—Ajit

Some scientists theorize that babies look more like their fathers than their mothers so that nature can prove to the father that the baby is indeed his. Once the father is convinced, the baby can morph to look more like the mother. My own theory is that, since babies are often bald, wrinkled and far from attractive, they tend to look more like their fathers. As for your question: Given the rarity of attractive males, I suspect that the (very) few that fit the bill get a larger advantage.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Erasing Email and Placebo Performance

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Recently, the German auto maker Daimler gave employees the option of automatically deleting all emails that arrive while they’re on vacation. Senders get a note suggesting that they resend their email later or write to other colleagues who are still in the office. This way, employees don’t have to face overflowing inboxes when they return. Is this a good idea?

—Kathleen

Not having to worry about email while you’re on vacation sounds wonderful, and this policy will probably boost employees’ well-being—though, of course, some will still wonder what they might have missed.

That said, the Daimler approach seems pretty extreme, and it deals with the symptoms rather than the root problem. In my experience, email stresses people out constantly, not just during vacations. We get too much email every day of the year; we spend too much time responding to it and worrying about it. Email correspondence in many corporations is so out of hand that it leaves almost no time for any actual work.

If the bosses at Daimler really care about their employees’ welfare, why not tackle the inefficiencies of this communication channel—and work to reduce their overall email load? How about announcing that no email is allowed between 9 and 11 a.m. and again between 1 and 3 p.m.? Or what if they limited people to just 10 emails a day? (Does anyone really have more than 10 important things to say in a day?)

______________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’ve read a lot about the placebo effect. Does that mean it won’t work on me?

—Marco

It turns out that placebos operate to some degree outside of our awareness—which means that even when we know a particular medication is a placebo, we can still benefit from it. So don’t worry about knowing too much. Just take two placebos and call me in the morning.

______________________________________________________

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Why we love to hate Michael Bay

Transformers 4 grossed $1 billion dollars worldwide. Now, it’s out on Blu-Ray to add to that total. This has left many wondering what South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone once famously pondered: “Why does Michael Bay get to keep on making movies” when his movies seem so terrible?

Well, modern consumer scientific research finally has an answer to this puzzle, and the answer isn’t just our poor taste in movies. We love seeing Michael Bay movies, because even if we don’t like the movies, we get to feel the “joy of judging.” This joy explains a lot of the modern entertainment economy, from watching reality TV to live tweeting the MTV Music Video Awards—two other examples where people tune into content they somewhat hate but love to somewhat hate.

With Bay’s movies, we enjoy the process of making snarky comments as we watch, searching for plot holes, and talking about how he is doing wrong by the source material. The movie could be bad, but the time we spend in the theater with the movie is fun.

From Hollywood movies to Harvard research, the idea that consumers crave engagement not just quality in their entertainment is becoming apparent.

The joy of judging and engagement gears into overdrive with Bay movies, as these pleasures are maximized when we feel some mastery and identity in the area. This is what makes Michael Bay’s movies so magnetic even if they also seem sort of repulsive; he consistently chooses topics that we have lots of knowledge of and that relate to our childhood identities (i.e., Transformers, Ninja Turtles).

We want to be a part of the community discussing these movies. So it does not matter whether Transformers 4 is good or not. We have to see it if we want to talk about the topic of Transformers.

Or consider The Amazing Spider-Man 2, a film that borrows heavily from the Michael Bay playbook of huge glossy visual imagery. That movie was not so good, was it? And comic fans knew that ahead of time. But did many of them still go? Absolutely. Why? Because the Spider-Man fans had to know whether the director got Spider-Man’s personality or the classic Gwen Stacy’s “arc” right.

Movies and television do not need to be good. The right type of movies and television are just a springboard for “second-level” enjoyment through Twitter, blogs and conversations.

So why does Michael Bay get to keep on making movies? Because bashing Bay is fun. While it might be tempting to feel bad for Bay, it’s worth remembering that all this Bay bashing means over $5 billion in box office total alone for the director. So good or bad, the movies are profitable and that’s what the movie business is all about.

Troy Campbell is an experimental researcher of consumer enjoyment and identity at Duke University and the Center for Advanced Hindsight.

You may also like “Why Who Plays Batman Matters” and “The Power of Modern Stand Up Comedy” by Troy Campbell.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like