Ask Ariely: On Meaningful Meals, Ideal Interviews, and Quick Consequences

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

My retired parents and I usually go out for lunch every other Sunday. We have been taking turns paying the check, but I know that I make more money than they do. Should I start paying for all the meals or at least cover the tip when they are paying?

—Andrew

Since you’ve established a custom of taking turns paying for meals, I think you should continue on that basis. Think of these meals as gifts that you are giving each other: The purpose of gift-giving is to help strengthen relationships rather than a strictly financial exchange. If you are worried about potential strain on your parents, you can offer to pay some of their other bills or give them a yearly cash gift, but I would separate the issue of their finances from the weekly tradition that you have established.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am applying for a CFO role at a public company. I am competing for the job with several other candidates, and the interviews with the board of directors will take place over the course of a week. Should I try to schedule my interview early in the week, late in the week or somewhere in the middle?

—Eric

There are two countervailing forces here. One is the exhaustion of the people interviewing you, which will likely increase over the course of the week. When people get tired, they’re more likely to make negative decisions. There’s a disturbing study on judges’ decisions to grant parole, showing that they are twice as likely to accept a prisoner’s application when they decide in the morning than at the end of the day. From that perspective, it’s better for your interview to take place on Monday.

On the other hand, the “recency effect” says that people are more likely to remember the most recent information. If the board is making its decision after the last interview, it would be to your advantage to be later in the week, so that you’ll still be prominent in their memories. The question is which force is going to be stronger. If you think the process is going to be exhausting for the people interviewing you, go early in the week; if not, try to go late.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

In general, what do you think are the domains where we make our best and worst decisions?

—David

People are generally better at making decisions about the physical world than they are when it comes to the mental world. That’s because when we make physical mistakes we see the consequences right away—think about the consequences of bad driving—while mistakes that we make in the mental world take much longer to appear—such as the consequences of making bad choices in elections.

This difference came home to me on a recent trip to London. The British have been able to create a material environment that is just amazing, from the beauty of the buildings to the quality of public transportation. Yet the political crisis in the U.K. suggests that when it comes to making decisions about the future of their country, they are finding things much tougher to manage.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

The (un-)expected link between the human and the artificial mind

Understanding the human mind is key to the better design of artificial minds.

A short report based on a paper by Darius-Aurel Frank, Polymeros Chrysochou, Panagiotis Mitkidis, and Dan Ariely

Technology around us is becoming smarter. Much smarter. And with this increased smartness come a lot of benefits for individuals and society. Specifically, smarter technology means that we can let technology make better decisions for us and let us enjoy the outcome of good decisions without having to make the effort. All of this sounds amazing – better decisions with less effort. However, one of the challenges is that decisions sometimes include moral tradeoffs and, in these cases, we have to ask ourselves if we are willing to allocate these moral decisions to a non-human system.

One of the clearest cases for such moral decisions involves autonomous vehicles. Autonomous vehicles have to make decisions about what lane to drive in or who to give way at a busy intersection. But they also have to make much more morally complex decisions – such as choosing whether to disregard traffic regulations when asked to rush to the hospital or to select whose safety to prioritize in the event of an inevitable car accident. With these questions in mind it is clear that assigning the ability to make decisions for us is not that easy and that it requires that we have a good model of our own morality, if we want autonomous vehicles to make decisions for us.

This brings us to the main question of this paper: how should we design artificial minds in terms of their underlying ethical principles? What guiding principle should we use for these artificial machines? For example, should the principals guiding these machines be to protect their owners above others? Or should they view all living creatures as equals? Which autonomous vehicles would you like to have and which autonomous vehicles would you like your neighbor to have?

To start examining these kinds of questions, we followed an experimental approach and mapped the decisions of many to uncover the common denominators and potential biases of the human minds. In our experiments, we followed the Moral Machine project and used a variant of the classical trolley dilemma – a thought experiment, in which people are asked to choose between undesirable outcomes under different framing. In our dilemmas, decision-makers were asked to choose who should an autonomous vehicle sacrifice in the case of an inevitable accident: the passengers of the vehicle or pedestrians in the street. The results are published under open-access license and are available for everyone to read for free at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-49411-7.

In short, what we find are two biases that influence whether people prefer that the autonomous vehicle sacrifices the pedestrians or the passengers. The first bias is related to the speed with which the moral decision was made. We find that quick, intuitive moral decisions favor killing the passengers – regardless of the specific composition of the dilemma. While in deliberate, thoughtful decisions, people tend to prefer sacrificing the pedestrians more often. The second bias is related to the initial perspective of the person making the judgment. Those who started by caring more about the passengers in the dilemma ended up sacrificing the pedestrians more often, and vice versa. Interestingly overall and across conditions people prefer to save the passengers over the pedestrians.

What we take away from these experiments, and the Moral Machine, is that we have some decisions to make. Do we want our autonomous vehicles to reflect our own morality, biases and all or do we want their moral outlook to be like that of Data from Star Track? And if we want these machines to mimic our own morality, do we want that to be the morality as it is expressed in our immediate gut feelings or the ones that show up after we have considered a moral dilemma for a while?

These questions might seem like academic philosophical debates that almost no one should really care about, but the speed in which autonomous vehicles are approaching suggests that these questions are both important and urgent for designing our joint future with technology.

Ask Ariely: On Craving Companions, Finding Fairness, and Delaying Decisions

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

I started college a couple of weeks ago, and I find myself very preoccupied about whether the people I’m meeting like me. Do you have any advice about how I can relax around people?

—Bronwyn

You will be relieved to know that most of us tend to underestimate how much people enjoy our company. In 2018, Erica J. Boothby and colleagues published a paper about the “liking gap”—the difference between how much we think other people like us and how much they actually like us. In one of their studies, they asked first-year college students to rate how much they liked a given roommate and how much they believed their roommates liked them, starting in September and continuing throughout the school year.

They found that participants systematically underestimated how much they were liked. In fact, it wasn’t until May, after living together for eight months, that people accurately perceived how much they were liked. So try to focus your social energy on spending quality time with friends and don’t worry too much about the outcome.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I work for a nonprofit organization that offers mindfulness retreats for teens. Our tuition model is that we request 1% of a family’s income, up to $2,000, for a week-long retreat. We feel that this model is fair, but some higher-income families object to paying more than others for the same service. Why do they feel this way, when the cost is such a small share of their income?

—Tom

Our perception of what is fair depends to a large degree on what we’re being asked to give up to achieve a fair outcome. In your arrangement, people with more money are being asked to pay more, so they are likely to see a fixed price for tuition as being more fair than a sliding scale—and vice versa for families with less money.

One way to try to overcome this bias is what the political philosopher John Rawls called the “veil of ignorance.” In this approach, people are asked to design an imaginary society they will have to live in, without knowing whether they are going to be rich or poor. This means that they have to decide what is fair before they know how much they will personally stand to gain or lose from any given arrangement—for instance, the tax rate. Maybe you can try an exercise of this sort related to tuition as part of your mindfulness teaching.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

I have an aging but perfectly fine car and waste a lot of time pining for something more modern and comfortable. But I haven’t found a new model I love, and with technological improvements happening so fast, cars are getting better every year. Should I wait for the perfect car to come along or should I compromise and buy something now?

—Alex

My sense is that if you don’t like any of the available options, it means you’re not yet ready to make a change. Happiness isn’t just about what we have and don’t have; it’s also about not constantly looking for something better. Why don’t you decide that you won’t look at new cars for a certain period—say, two years—and then give yourself a three-month window to research a purchase. At the end of that time, you will pick the best option available. This way, you won’t waste time and energy on an open-ended search.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Ask Ariely: On Balancing Birthdays, Valuing Vacations, and Finding Fulfillment

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I am a widow, and my friendships are very important to me. But many of my friends are couples, and each year I end up buying birthday gifts for both the husband and the wife, plus an anniversary gift. While I always get a nice present in exchange on my birthday, the balance of gift-giving seems unfair. Is there a more evenhanded way to exchange gifts?

—Carol

It’s very hard to shift social norms about gift-giving, especially when a pattern is well established. The best approach might be to try to replace the current norm with a new one. For example, what if you told your friends that you are concerned about the environment and want to try to reduce your level of consumption and waste, so you are planning to start giving cards instead of gifts. Ask them to help you with this commitment by giving you cards in exchange. This way, you would be appealing to a moral principle, rather than telling the that all you are trying to do is to save SOME money.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m planning a vacation, and I’m considering a prepaid, all-inclusive resort, so that I won’t have to worry about the cost of every drink and sandwich. But I’m concerned that the all-inclusive package won’t be as good an experience as some of the other, pay-as-you-go options that I’m looking at. Is prepaying always the best choice?

—Saurabh

You’re certainly right that an all-inclusive resort isn’t always the highest-quality option. But you have to remember that what’s most important is whether you’re going to enjoy the experience you have. Constantly having to make decisions about what to buy can detract from your vacation experience, even if the hotels or restaurants you end up patronizing are of better quality.

In general, when you make a decision, it’s better not to ask “Am I choosing the absolute best option?” Instead, you should consider your enjoyment of the experience as a whole, including your ability to relax and your peace of mind.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I grew up in a working-class household, and I’ve been upwardly mobile in my career, but I’ve recently begun to feel that my job is meaningless. Should I think about my work merely as a way to make money to survive? Or would it be better for me to look for a job that I can take pride in as part of my identity?

—Ella

The research is very clear that finding meaning in your job is necessary for happiness. At the same time, if too much of your identity is tied up in your job, it can make you more vulnerable to work-related stress. A study conducted in 1995 by Michael R. Frone, Marcia Russell and M. Lynne Cooper found that people who strongly connected their identities with their jobs were much more sensitive to work stressors than those who thought about their work in a more casual and detached way.

Ideally, you should look for work that gives you a sense of pride and meaning, but you should also remember that a job doesn’t define you, and that there are other, equally important parts of your identity.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Amazing Decisions!

Hello all,

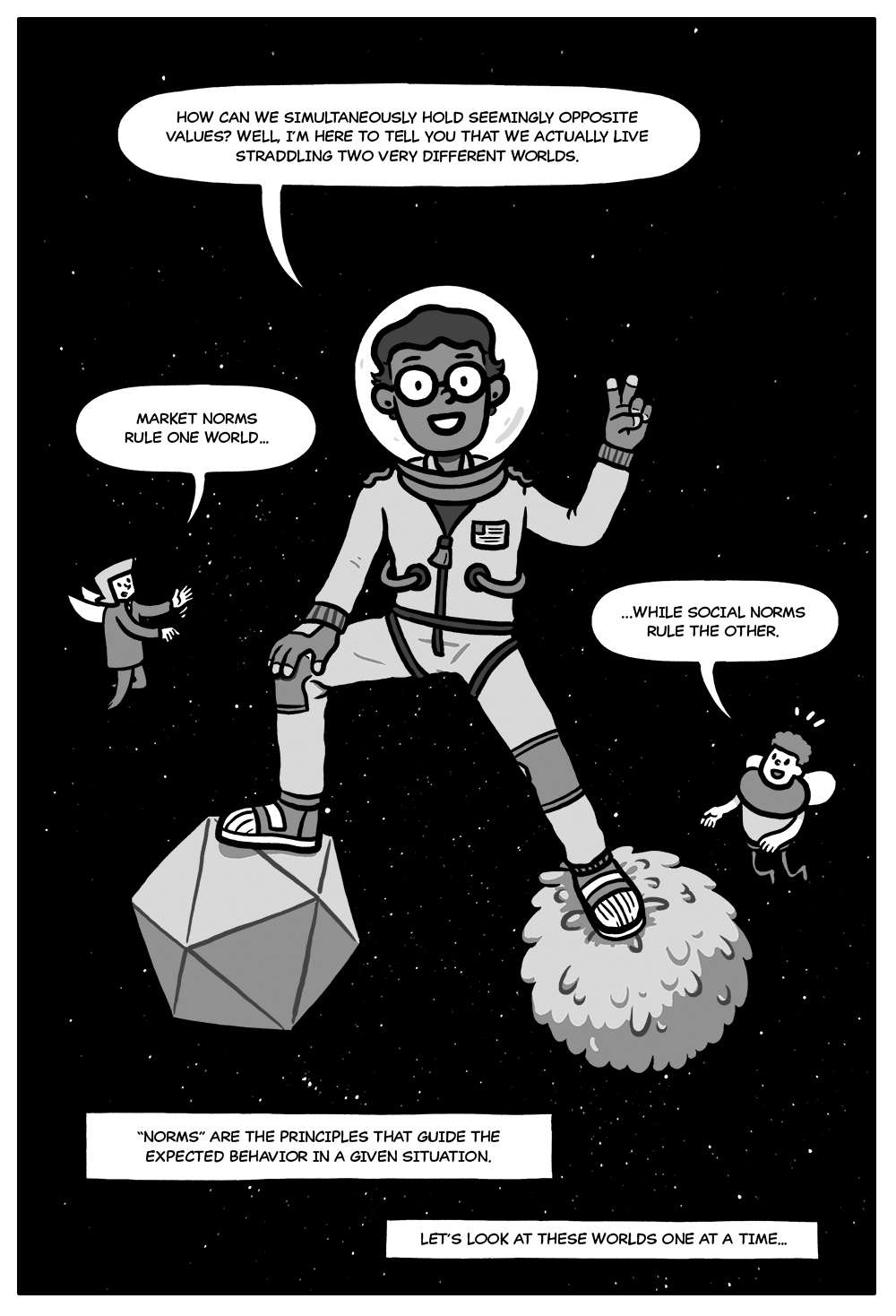

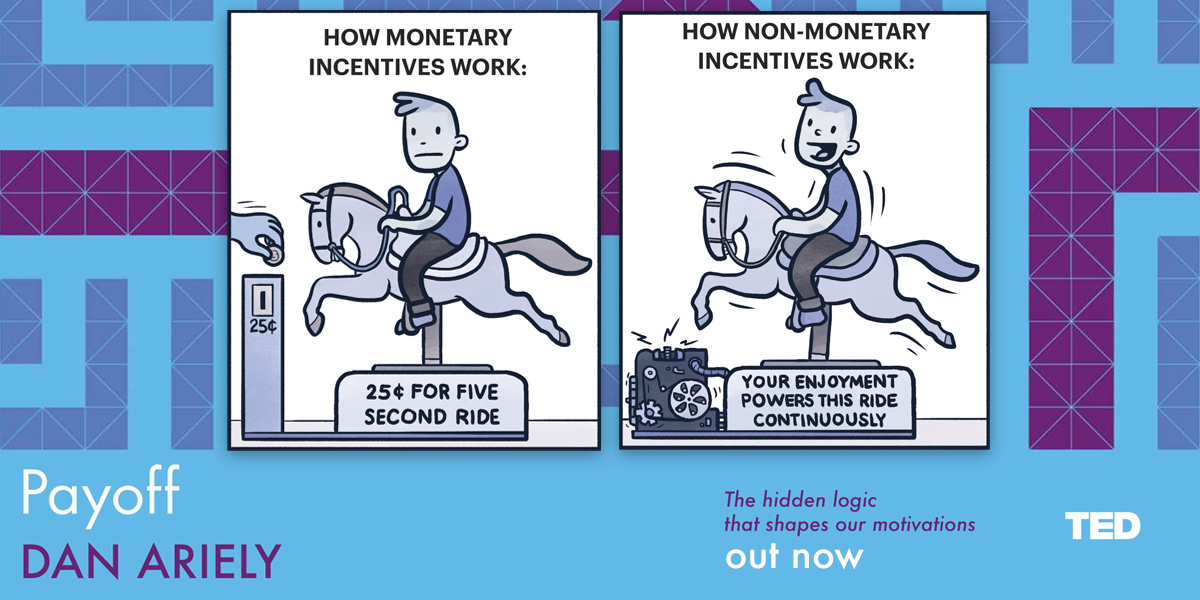

I’m excited to share with you my new graphic novel with illustrator Matt R. Trower, Amazing Decisions: The Illustrated Guide to Improving Business Deals and Family Meals. This book will help you understand how to navigate the complex and curious interaction between social norms and market norms… and make better decisions for it!

Please watch this video to understand more, and find the book here on Amazon or in your local bookstore!

Ask Ariely: On Overwhelming Options, Frustrating Fees, and Valuable Vocations

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Does the fact that so many Democrats are running for President in 2020 make it more difficult for voters to choose among them? I’m especially interested in politics, and even I find it hard to compare each candidate’s positions. I wonder if many Democratic voters will simply give up on paying attention to the primaries.

—Tracy

In behavioral science, we call this phenomenon “the paradox of choice.” While many people report that they like having more choices, having too many choices can end up making it impossible to make a decision at all. For example, when people are given a lot of flavors of jam to choose from, they tend to sample more flavors, but they are less likely to actually buy one of them. In the case of the Democratic primaries, the number of candidates is certainly overwhelming, and I think it is likely to decrease voter turnout.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

During a recent doctor visit, I was asked to sign an agreement saying that if I missed a future appointment I would have to pay a $50 fee. I thought this was excessive and refused to sign. Does this kind of policy really get more people to show up for medical appointments?

—George

Negative incentives—in other words, punishments—are more complex than they seem and can backfire. One of my favorite studies on this topic is by the economists Uri Gneezy and Aldo Rustichini, who showed that when a day-care instituted a fine for late drop-offs, parents became even less likely to arrive on time. Instead of viewing the fine as a punishment, parents saw it as a way to pay for the right to be late, and they took advantage of this service without guilt.

In your case, I would expect to see a similar result: Patients might feel more entitled to miss appointments if they know they can pay a fee for it. In addition, the system will probably make patients even more furious when doctors are inevitably late, since it implies that the doctors think their own time is more valuable than that of their patients.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

Do people’s salaries tend to accurately reflect the value they contribute to society? Can we assume that if someone makes a lot of money, they are adding significantly more value than someone who makes only a little?

—Richard

On the contrary, there are many people who create a lot of value and don’t get paid much, as well as many who create very little value and get paid well. One of the best examples of this mismatch is teachers. A paper by Raj Chetty and colleagues in the American Economic Review estimated how much of an impact teachers have on the future of the students in their classes.

They found that students with strong teachers are more likely to attend college, have higher lifetime salaries and are less likely to become pregnant as teenagers. They estimated that replacing a teacher in the bottom 5% with an average teacher would increase their students’ lifetime income by $250,000 per classroom. Yet obviously, teachers don’t make anywhere close to that figure. Maybe one day we will evolve as a society and base people’s salaries on their actual contribution to the common good.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal.

Ask Ariely: On Staying Safe, Cultivating Confidence, and Deciding Deadlines

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

India has one of the highest rates of road-accident mortality in the world. Our Supreme Court in India mandated the use of helmets when riding a motorcycle or scooter, yet many people don’t obey the law. Why is it that people don’t wear helmets? Do they just not understand the risk?

—VN

The problem is that while we know riding a motorcycle without a helmet is risky, our experience can provide us with a false sense of safety. If you decide to ride without a helmet once, the odds are that nothing bad will happen to you, since the probability of getting into an accident on any given ride is low. As a result, your bad behavior is reinforced, and you do it again and again until, eventually, your luck runs out. This is a good example of why it’s a bad idea to rely on intuition about what is safe, instead of trusting the actual data.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I was attacked by a dog when I was 7, and it left me with serious injuries and scars. Now that I’m an adult, I realize that my appearance is holding me back from pursuing things I enjoy. What can I do to overcome this problem?

—Joe

As someone who was badly injured in a fire as a teenager, I have to admit that my own concern with the way I look is still with me—particularly when people shake my injured hand.

But there are two rays of light. The first is something called the spotlight effect, which says that all of us pay a lot more attention to ourselves than other people pay to us. This was elegantly demonstrated in a study in 2000 by Thomas Gilovich and colleagues, who asked some Cornell students to walk into a fraternity party wearing embarrassing Barry Manilow T-shirts. After the party, the researchers asked them how many people noticed their shirts and what the social implications were. The participants believed that everybody noticed and that it hurt their social reputations. When the researchers asked everyone else at the party, it turned out almost nobody noticed the shirts.

The second hopeful fact is that with time and practice, your sensitivity to your appearance will go down, even if it’s never completely eliminated. I hope that this problem won’t prevent you from going out into the world and making the most of your limited time on earth.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

I work in human resources, and I’m trying to motivate our employees to complete a short online training program. The training is very simple, but no one seems to get it done. Should I give them a deadline of a month to finish it, or will that just cause more delay?

—Archie

Deadlines are very important—when we have lots of demands on our time we need deadlines to help us set priorities. However, people also use deadlines as a source of information about the complexity of the task. In a paper published earlier this year in the Journal of Consumer Research, Meng Zhu and colleagues found that giving people longer deadlines led them to believe that the task was much harder, which in turn increased how much they procrastinated. So for an easy task like completing an online training program, set a short-term deadline, so that people will think the task is easy to accomplish and get right to it.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Delaying Decisions, Generating Generosity, and Enhancing Experiences

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I take a lot (and I mean a lot) of time to reach a decision. I keep consulting, thinking, making comparison charts, googling, asking experts. But when the time finally comes to decide, I’m never fully convinced that I’m making the right choice. How can I stop second-guessing myself?

—Ramesh

When people agonize over making a decision, they usually aren’t thinking enough about the opportunity cost of their time. For instance, if you spend months thinking about whether to make a career change, you will have lost time that you could have spent actually building your new career. That’s why it is useful to set a time limit for any decision you face. Tell yourself, “I’m going to decide by Friday,” and if you haven’t decided by then, simply toss a coin.

Another mistake people often make is mulling over decisions they have already made. Regret and reflection are useful only if they teach us lessons we can use in future decision-making, not when we use them as a form of self-punishment. So try to focus not on the decision you have just made but on what you could do differently in the future.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I was traveling in New York City and was about to board a bus to the airport when I realized that I’d forgotten my MetroCard. To my surprise, a stranger who was watching approached me and gave me her card. I thanked her and tried to pay her for it, but she refused. Are people more generous than we usually give them credit for?

—Yoram

People have a tremendous capacity for generosity, but usually it only emerges under the right conditions. The first condition is that we need to see an individual in need, rather than masses of people suffering: It is easier to empathize with one person than with a large group. Second, we need to be able to identify with the person in need, to put ourselves in their shoes. In your case, both conditions were met: You were one person in need, and the people around you could easily imagine how they would feel if they were in your position since they were also waiting for the bus.

___________________________________________________

Hi, Dan.

Everyone talks about the importance of friendship, but does sharing an important experience with another person actually make it better?

—Alex

It depends on whether the experience in question is a good or bad one, and on whether the person you are sharing it with is close to you or not.

In a 2014 study in the journal Psychological Science, Eric Boothby and colleagues showed that eating chocolate along with another person made the experience more enjoyable, but eating very dark chocolate with another person made it taste even worse. The presence of others seems to make positive experiences more positive and negative experiences more negative.

Other studies have shown that experiencing pain—for instance, sticking your hand in an ice bath—becomes more intense when it is shared with a friend than with a stranger. This suggests that, to enhance good experiences, we should invite friends to participate—but when it comes to unpleasant experiences, it is best to go it alone.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Ask Ariely: On Dramatic Defaults, Traveler Tips, and Restaurant Risks

Here’s my Q&A column from the WSJ this week — and if you have any questions for me, you can tweet them to @danariely with the hashtag #askariely, post a comment on my Ask Ariely Facebook page, or email them to AskAriely@wsj.com.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I know that people are more likely to make smart decisions—about, say, contributing early and often to a retirement savings fund—if they’re nudged into it by default settings. How powerful is this effect? Do defaults push people a bit or change their choices dramatically?

—Tom

You’ve put your finger on one of the key findings of behavioral economics. Shlomo Benartzi and Richard Thaler, among others, produced probably the field’s greatest success by encouraging employers to create retirement benefits packages whose default options are set for savings. Such packages used to require employees to enroll if they wanted to start saving. By switching the default, so that employees were automatically enrolled and had to act if they wanted to stop putting aside money, saving rates increased dramatically.

But what effect does changing the default setting have compared with other incentives to save? Take a recent study by Michael Callen, Joshua Blumenstock and Tarek Ghani. They worked with Roshan, a mobile communications provider in Afghanistan, to create a savings plan for its 1,000-person workforce. Half the participants were given a default of “opt in” (and had to call to leave the plan), and the other half was defaulted to “opt out” (and had to call to start saving).

The researchers wondered how much changing the company’s matching level and the employees’ default settings would increase savings. They found that automatic enrollment had about the same effect on participation as providing the pricey incentive of a 50% matching contribution from the firm. Default settings, they concluded, are powerful indeed—perhaps not enough to make businesses stop matching contributions for their workers, but more than enough to make them sweat the default details.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

On vacation in Mexico, I saw a hardworking server waiting on guests at a resort—who didn’t leave a tip. I can’t imagine they would have behaved this way in our native Canada. Did the fact that they had purchased an “all-inclusive” vacation have anything to do with it?

—Kevin

Several forces were probably at work. First, some all-inclusive vacations aren’t clear about tips, which may incline us to think gratuities are covered. Second, remember the saying: “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.” When we travel, we become slightly different versions of ourselves—and can act more freely without tainting our own reputations, at least in our own eyes. Finally, immorality often stems from our ability to convince ourselves that we’re doing something OK—even if we know that we’d want people to behave better if we were on the receiving end.

___________________________________________________

Dear Dan,

I’m often flummoxed by long restaurant menus, so I’ll pick a familiar dish—and feel that I haven’t gotten the most out of my dining experience. Any dining advice?

—Tom

Trying new things makes life more interesting, but the fear of making mistakes can drive us to play it safe. Restaurants are great places for a risk. The most you can lose is one meal, and you can always ask for something else if you hate your adventurous dish (just tip well). So I often ask the waiter for the most unusual dish on the menu.

See the original article in the Wall Street Journal here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like