Upside of Irrationality: Chapter 7

Here I discuss Chapter 7 from Upside of Irrationality, Hot or Not? Adaptation, Assortative Mating, and the Beauty Market.

Asking the right and wrong questions

From a behavioral economics point of view, the field of financial advice is quite strange and not very useful. For the most part, professional financial services rely on clients’ answers to two questions:

- How much of your current salary will you need in retirement?

- What is your risk attitude on a seven-point scale?

From my perspective, these are remarkably useless questions — but we’ll get to that in a minute. First, let’s think about the financial advisor’s business model. An advisor will optimize your portfolio based on the answers to these two questions. For this service, the advisor typically will take one percent of assets under management – and he will get this every year!

Not to be offensive, but I think that a simple algorithm can do this, and probably with fewer errors. Moving money around from stocks to bonds or vice versa is just not something for which we should pay one percent of assets under management.

Actually, strike that. It’s not something we should do anyway, because making any decisions based on answers to those two questions don’t yield the right answers in the first place.

To this point, we’ve run a number of experiments. In one study, we asked people the same question that financial advisors ask: How much of your final salary will you need in retirement? The common answer was 75 percent. But when we asked how they came up with this figure, the most common refrain turned out to be that that’s what they thought they should answer. And when we probed further and asked where they got this advice, we found that most people heard this from the financial industry. Sort of like two months salary for an engagement ring and one-third of your income for housing, 75 percent was the rule of thumb that they had heard from financial advisors. You see the circularity and the inanity: Financial advisors are asking a question that their customers rely on them for the answer. So what’s the point of the question?!

In our study, we then took a different approach and instead asked people: How do you want to live in retirement? Where do you want to live? What activities you want to engage in? And similar questions geared to assess the quality of life that people expected in retirement. We then took these answers and itemized them, pricing out their retirement based on the things that people said they’d want to do and have in their retirement. Using these calculations, we found that these people (who told us that they will need 75% of their salary) would actually need 135 percent of their final income to live in the way that they want to in retirement. If you think about it, this should not be very surprising: If you add 8 hours (or more) of free time to someone’s day, they will probably not want to spend this extra time by going for long walks on the beach and watching TV – instead they may want to engage in activities that cost money.

You can see why I’m confused about the one-percent-of-assets-under-management business model: Why pay someone to create a portfolio that’s 60 percent too low in its estimation?

And 60% is if you get the risk calculation right. But it turns out the second question is equally problematic. To show this, we also asked people to tell us how much risk they were willing to take with their money, on a ten-point scale. For some people we gave a scale that ranges from 100% in cash on the low end of the risk scale and 85% in stocks and 15% in bonds on the high end of the risk scale. For other people we gave a scale that ranges from 100% in bonds on the low end of the risk scale and buying only derivatives on the high end of the risk scale. And what did we find? People basically looked at the scale and said to themselves “I am a slightly above the mean risk-taker, so let me mark the scale at 6 or 7.” Or they said to themselves “I am a slightly below the mean risk-taker, so let me mark the scale at 4 or 5.” In essence, people have no idea what their risk attitude is, and if they are given different types of scales they end up reporting their risk attitude to be very different.

So we have an industry that asks one question it’s giving the answer to, and a second question that assumes that people can accurately describe their risk attitude (which they can’t). This saddens me because, while I think that financial advisors are overpaid for the service they provide, in principle they could contribute much more, and they could even deserve their salary. But only if they start offering a more useful service, one that they are in the perfect position to provide. Money, it turns out, is incredibly hard to reason about in a systematic and rational way (even for highly educated individuals). Risk is even harder.

Financial advisors should be helping their clients with these tough decisions! Money is about opportunity cost. Every time we think about buying a car or going on vacation we should be asking ourselves what we won’t be able to afford in the future if we go ahead and make this purchase. And that’s where the financial advisor should come in.

It’s possible that the best financial advisors already do help in this way, but the industry as a whole does not. It’s still centered on the rather facile service of balancing portfolios, probably because that’s a lot easier to do than to help someone understand what’s worthwhile and how to use their money to maximize their current and long-term happiness.

The fact is that money is hard to think about and we do need help with making financial decisions. The financial consulting profession has an opportunity to reinvent itself to service this need. And if they do, it will be beneficial for both financial advisors and their clients.

——————–

A shorter version of this appeared at hbr.org

Upside of Irrationality: Chapter 6

Here I discuss Chapter 6 from Upside of Irrationality, On Adaptation: Why We Get Used to Things (but Not All Things, and Not Always).

If the video is not working — www.youtube.com/watch?v=9pzB3NXr7ys

FREE! in Swedish Medicine

I recently learned of an interesting innovation in medical pricing coming from Sweden. This pamphlet from the healthcare authority states (translated): “If you have a respiratory problem and you don’t take antibiotics for it during your first visit to the doctor, you have the right to a second visit within five days free of charge”.

This approach is using the power of FREE! in an attempt to get people to reduce their use of antibiotics. But, I wonder if this approach might be too powerful, such that it will get people who do need antibiotics not to get them. And I also wonder whether this approach will be particularly effective on people who have less money — which might not be ideal.

Better (and more) Social Bonuses

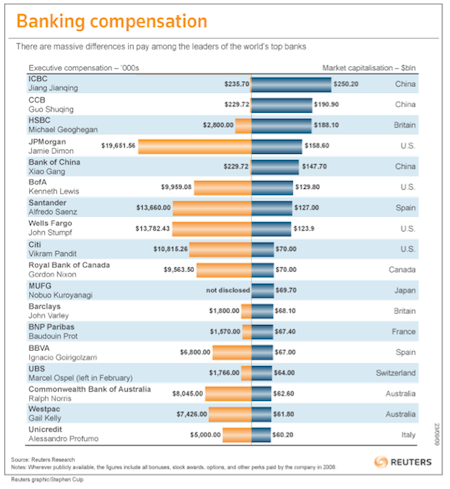

Over the last few years, many individuals (myself included) have been feeling tremendous anger about the level of executive compensation in the US, an anger that is particularly strong against those in the financial sector. As you can see in the chart below, there is an incredible gap between CEO compensation in the US compared to most other countries. Bankers are paying themselves exorbitant wads of cash, seen in both in their salaries and bonuses. And in their defense, the bankers in question claim that such extravagant wages are essential to properly motivate them, and that without such motivation they would just go and find a job somewhere else (they never exactly specify which jobs they will get and who will pay them more, but this is another matter).

Inordinate compensation levels aside, it is important to try and figure out more generally how payment translates into motivation and performance. There is a general assumption that more money is more motivating and that we can improve job performance by simply paying people more either in terms of a base salary, or even better as a performance-based incentive – which are of course bonuses. But, is this an efficient way to compensate people and drive them to be the best that they can be?

A new paper* by Mike Norton and his collaborators sheds a very interesting light on the ways that organizations should use money to motivate their employees, boost morale and improve performance – benefiting both employees and their organizations. The researchers looks at a few ways that money can be spent and how that affects outcomes such as employee wellbeing, job satisfaction and actual job performance. Specifically, they examine the effect of prosocial incentives, where people spend money on others rather than themselves, and they find that there are many benefits to spending money on others (think about the inherent joy of gift-giving).

In the first experiment, the researchers gave charity vouchers worth $25 or $50 to Australian bank employees and asked them to donate the money to a charity of their choice. Compared to people who did not receive the charity vouchers, those who donated $50 (but not $25) claimed to be happier and more satisfied with their jobs.

The second experiment took the concept of prosocial incentives a step further by directly comparing people who were asked to spend money on themselves (a personal incentive) with those who were asked to purchase a gift for a teammate (a prosocial incentive). This experiment took place in two different settings — with sales and sports teams — and looked at a broader range of outcomes. It not only examined employee satisfaction, but also the other side – benefits to the organization in terms of employee performance and return on investment. While neither sales nor sports teams improved when people were given money to spend on themselves, Norton and his colleagues found vast improvements for those who engaged in prosocial spending. While they were purchasing a gift for a teammate, they also became more interested in their teammate and were happier to help them further in multiple other ways.

If we compare these experiments, we can also see that while a gift of $25 did not make a difference when it was donated to a faceless and impersonal charity, a gift of $20 provided numerous positive outcomes when it was given in the form of helping out a teammate. Thus, it appears that we can reap the greatest benefits when we spend money on others, and even more when we spend money on close others.

Taken together, these results also suggest that our intuitions are leading us down the wrong path when we assume that we will be happiest and most motivated when we earn money to spend on ourselves. The findings from this paper can be extended to recommendations for current business practices, particularly in cases where compensation is very high. In fact, Credit Suisse has gotten a head start on adopting the idea of prosocial spending, as it has recently implemented a program requiring its employees to donate at least 2.5% of their bonuses to charity. Now, is this just a PR trick to try and diffuse some of the anger that people feel these days about bankers, or is this a real effort to increase and improve motivation? I don’t know. But what is clear to me is that prosocial incentives, either in the form of charitable donations or team expenditures, can be an effective means of encouraging more positive behavior for the individual, their teammate and for society.

* Norton MI, Anik L, Aknin LB, Dunn EW & Quoidbach J (manuscript under review). Prosocial Incentives Increase Employee Satisfaction and Team Performance.

Upside of Irrationality: Chapter 5

Here I discuss Chapter 5 from Upside of Irrationality, The Case for Revenge: What Makes Us Seek Justice?.

Big City, Small Robot

Several years ago, I began to make human-dependent cardboard robots and place them on the streets of New York City. These little robots, which came to be known as Tweenbots (a combination of the words “between” and “robot”), roll at a constant speed, in a straight line, and have a flag that says that they are trying to get to a certain destination (e.g., the southwest corner of Washington Square Park). The flag asks for people to aim the Tweenbot in the right direction to reach its goal.

Several years ago, I began to make human-dependent cardboard robots and place them on the streets of New York City. These little robots, which came to be known as Tweenbots (a combination of the words “between” and “robot”), roll at a constant speed, in a straight line, and have a flag that says that they are trying to get to a certain destination (e.g., the southwest corner of Washington Square Park). The flag asks for people to aim the Tweenbot in the right direction to reach its goal.

New York City is a large and bustling place – and if one ascribes to the stereotypes about New Yorkers’ helpfulness, the outlook did not appear promising for these little cardboard robots.

On the other hand, the Tweenbots are irresistibly cute. They have a cheerful posture and move along at a bumbling pace. As you look down at them, the first thing you see is an iconic smiley face made of two large circles for eyes and a line for a mouth.

Scott McCloud, who writes about the theory of cartoons in his book Understanding Comics, explains the deeply embedded mental processes that compel us to interpret everything in our own image; we can’t help but transform two dots and a line into a face. For McCloud, the less realistic –the more abstract and iconic– a character’s features, the more easily we fill in the details based on our own perspective and imagination, “assigning identities and emotions where none exist.” We project ourselves onto characters so that we not only identify with them, we inhabit and become them.

Over the course of a few months, as I observed people interacting with the Tweenbots, I came to realize just how powerful their anthropomorphic and emotive qualities were. At first, I started to perceive this through people’s use of simple gestures that are commonplace in our everyday social interactions; when a pedestrian looked down at a Tweenbot’s smiling face, they couldn’t resist smiling back. This automatic mimicry is a sort of emotional contagion, and goes beyond unconsciously mirroring another’s expression – it also implies that you can “catch” or feel the emotions of another. I saw this automatic response over and over again, and hoped that by smiling in response to the Tweenbots, people were actually feeling happier. I also came to recognize that people were experiencing deeper emotional connections when, moments after they characterized the Tweenbot as happy and non-threatening, they seemed to consider the Tweenbot’s presence in the context of the big city and respond empathetically to their plight.

Empathy is being able to walk a mile in someone’s shoes, to vicariously experience and understand what another is going through. As I watched some people bend down and gently orient the Tweenbot in the right direction, it occurred to me that the Tweenbots were inviting people to extend beyond themselves to experience the city from the perspective of a tiny and tragically cheerful cardboard robot. With their improbable presence on city streets, Tweenbots are the quintessence of vulnerability, of being lost, and of having intention without the means of achieving their goal alone. We all know –or can imagine– what it feels like to be lost or helpless in the face if the city’s massive network of streets, subways and crowds. But this overwhelming milieu may also be the reason that we ignore others who may need help as we go about our daily routines. The unexpected appearance of the Tweenbot, along with their disarming appearance, disrupted the self-focused navigation of the city, inviting people to stop and interact. New York brought the Tweenbots to life when people projected their own feelings onto the simple forms of the Tweenbots, and in a small way for just an instant, they perhaps saw themselves looking up from the sidewalk as a helpless cardboard form.

It seemed entirely possible that this empathetic connection was what motivated so many people to help the Tweenbots. Every time a Tweenbot got stuck in a pothole or started to grind futilely against a curb, someone would come to its rescue. Strangers, who seconds before would have no reason to talk to one another, came together to help. People talked to the Tweenbots, and asked for directions on the Tweenbot’s behalf when they did not know which direction to aim it. Of all the amazing interactions, my favorite was when one man turned a Tweenbot back in the direction it had just come, saying out loud to it “you can’t go that way, it’s toward the road.”

~Kacie Kinzer~

To learn more about the Tweenbots, you can check out the website here.

Tweenbots from kacie kinzer on Vimeo.

The Economics of Sterilization

When it comes to sterilization, Denmark has had a rather turbulent history. In 1929, in the midst of rising social concerns regarding an increase in sex crimes and general “degeneracy,” the Danish government passed legislation bordering on eugenics, requiring sterilization in some men and women. Between 1929 and 1967, while the legislation was active, approximately 11,000 people were sterilized – roughly half of them against their will.

Then, the policy was changed so that sterilization was still available, still free, but not involuntary. And as you might expect, the sterilization rate in Denmark dropped down dramatically – and stayed this way until 2010.

Now we come to 2010. In only a few short months, the sterilization rate increased fivefold. No, this was not a regression to the old legislation; it was a result of free choice…

What happened? Last year, the Danish government announced that sterilization, which had been free, would cost at least 7,000 kroner (~$1,300) for men and 13,000 kroner (~$2,500) for women as of January 1st, 2011. Following the announcement, doctors performing sterilizations found that their patient load suddenly surged. People were scrambling to get sterilized while it was still free.

Now, it could be that the people who were already planning on getting sterilized at some point in the future just made their appointments a bit sooner, and conveniently saved some money. But I can also imagine that (much like our research on free tattoos) there were many people who did not really think much about sterilization before the price change, but were so averse to giving up such a good deal that it pushed them to take the offer and undergo a fairly serious procedure.

And although we usually don’t think about sterilization as an impulse purchase, it might just become one when a free deal is about to be snipped.

Amy Winehouse & responsibility

The recent death of Amy Winehouse should make us pause and consider the question of personal and shared responsibility. Was she solely responsible for her tragic outcome? Or was it somewhat the fault of the people around her? How do we want to think about the state of mind of a drug addict? And what does that say about their ability to make good decisions and hence their responsibility?

I am almost sure that if I were a jury member being presented with a case of a drug addict who committed a crime while in a highly emotional state of drug craving — that I would equate this state of mind to temporary insanity, and would find this to be a mitigating circumstance.

And if being in a state of drug craving can be considered a mitigating circumstance, shouldn’t this tell us that we should not expect too much personal responsibility from people who are in this state of mind? And shouldn’t the people around them (particularly the ones working with / for them) take control? There is a very nice saying that “friends don’t let friends drink and drive,” and I suspect that this rings even truer of drug cravings.

—

P.S. To clarify, my point here is not that Amy Winehouse is not to blame for her decisions, or that her friends are. Rather, I think that we need to back down from our chronic obsession with personal responsibility and realize that there are times when it is necessary to step in to help people who are not in a state to make the right decisions for themselves. Who knows, maybe the next Amy Winehouse’s daddy will try a little harder to keep her in rehab when she won’t go, go, go.

Honest Tea Declares Chicago Most Honest City, New York Least Honest

From the Huffington Post:

Would you still pay a dollar for Honest Tea if you could take it for free? On July 19, the company conducted an Honest Cities social experiment—it placed unmanned beverage kiosks in 12 American cities. There was a box for people to slip a dollar in, but there were no consequences if they did not pay.

Turns out, Americans (or at least Americans who like Honest Tea) are pretty gosh darn honest. Chicago was the most honest city, with 99 percent of people still paying a dollar. New York was the least honest city—only 86 percent coughed up the buck.

The full results:

Chicago: 99%

Boston: 97%

Seattle: 97%

Dallas: 97%

Atlanta: 96%

Philadelphia: 96%

Cincinnati: 95%

San Francisco: 93%

Miami: 92%

Washington, DC: 91%

Los Angeles: 88%

New York: 86%Honest Tea is donating all of the money collected, nearly $5,000, to Share Our Strength, City Year and Rails-to-Trails Conservancy. The company is matching the total, bringing the total donated to $10,000.

What kinds of things might have changed this very honest behavior?

Here are some open questions, or maybe future experiments to try:

1) What if the box for paying was not transparent? If it was opaque, then no one could see if the person in front of the box was really paying and there was no evidence that many people have paid before (based on the number of dollars that were there)

2) What if people approached the booth one by one and without being observed by anyone?

3) What if the experiment was conducted at night? What if people were slightly drunk?

4) What if there was an actor who would go by and take a bottle without paying? Would it make the other people be less honest? (I think so)

5) Who is more likely to be dishonest, people who come as individuals, or people who come in groups?

6) When it is sunny and people are happier, are they also more honest?

What is clear is that there are lots of interesting questions here.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like