Easing the Pain This Holiday Season

The image (and jingle) of the bells of Salvation Army volunteers is almost as synonymous with the holiday season as Santa Claus himself. However, the New York Times reported last month that a change may be coming to a street corner near you; the charity has begun testing the use of a digital donation system called Square that would allow passersby to donate via credit card, rather than have to worry about scrambling for loose change.

The image (and jingle) of the bells of Salvation Army volunteers is almost as synonymous with the holiday season as Santa Claus himself. However, the New York Times reported last month that a change may be coming to a street corner near you; the charity has begun testing the use of a digital donation system called Square that would allow passersby to donate via credit card, rather than have to worry about scrambling for loose change.

The article mentions two potential benefits of this kind of system. First, people are less likely to carry cash on them as they were in the past, and so Square’s credit card system provides people with a quick, simple, and convenient way to donate when they don’t have any real money handy (and with 1 in 7 Americans carrying at least 10 credit cards, this shouldn’t be a problem). Second, a credit card system would be safer because donations would not be vulnerable to theft like money in the kettle has always been.

Still, this credit card system may unintentionally have another significant benefit: it may lead people to want to donate more money than they would otherwise. There is a concept in behavioral economics known as the “pain of paying.” Simply put, it hurts us to spend (and part with) our money. And since buying things with a credit card is a less direct, less tangible way to part with money than using cash, it can feel less painful, and therefore lead people to spend more.

Assuming that this effect generalizes from buying products to donating to charities, Square’s credit card system may actually lead to larger total donations for the Salvation Army, whether it is because more people decide to donate, or because more money is donated by each individual. (Not to mention the possibility that people may feel silly choosing “loose change”-style amounts (e.g., 35 cents) to donate via credit card, and so may round up to the whole dollar for that reason alone).

So Square’s credit card system may, through behavioral economics, lead people to be more generous with their donations to the Salvation Army. If the Salvation Army uses this new system and winds up faring well, perhaps other charities should take note and consider implementing such a system as well.

Have a happy holiday season, everyone! And remember that doing the most good may be just a swipe away.

~Jared Wolfe~

Can beggars be choosers?

One day a few years ago I passed a street teeming with panhandlers, begging for change. And it made me wonder what causes people to stop for beggars and what causes them to walk on by. So I hung out for a while, engaging in a bit of discreet peoplewatching. Many people passed the beggars without giving anything, but there were a few who stopped. What was it that separated those who paused and gave money from those who didn’t? And what separated the more successful beggars from those who were less successful? Was it something specific about their situation, or their presentation? Was it the beggar’s strategy?

To look into this question, I called on Daniel Berger Jones, an acting student at Boston University who had just finished hiking around Europe. Not having shaved in months and already looking pretty scruffy, he was ready for the job (plus as part of his training to be an actor I figured it would be good for him to learn how to beg for money – at the time he did not see that particular benefit). So I found a street corner and placed him there to take on the panhandling trade. I asked Daniel to try a few different approaches to begging and to keep track of the approaches that made him more or less money. (Of course, after the experiment was over we donated all the money that he made to charity). The general setup was what we call a 2×2 design: When people walked by, Daniel would either be sitting down (the passive approach) or standing up (the active approach) and he would either look them in the eyes or not. So there were times when he was 1) sitting down and looking people in the eyes, 2) sitting down and not looking people in the eyes, 3) standing up and looking people in the eyes, or 4) standing up and not looking people in the eyes.

Daniel got to work, scrounging for money. He stayed on his corner for a while, trying the different approaches. And it turned out that both his position and his eye contact did, in fact, make a difference. He made more money when he was standing and when he looked people in the eyes. It seemed that the most lucrative strategy was to put in more effort, to get people to notice him, and to look them in the eyes so that they could not pretend to not see him.

Interestingly, while the eye contact approach was working in general, it was clear that some of the passersby had a counterstrategy: they were actively shifting their gaze in what seemed to be an attempt to pretend that he wasn’t there. They simply acted as if there was a dark hole in front of them rather than a person, and they were quite successful at averting their gaze.

At some point, something very interesting happened. There was another beggar on the street – a professional beggar – who approached young Daniel and said, “Look kid, you don’t know what you’re doing. Let me teach you.” And so he did. This beggar took our concept of effort and human contact to the next level, walking right up to people and offering his hand up for them to shake. With this dramatic gesture, people had a very hard time refusing him or pretending that they did not seen him. Apparently, the social forces of a handshake are simply too strong and too deeply engrained to resist – and many people gave in and shook his hand. Of course, once they shook his hand, they would also look him in the eyes; the beggar succeeded at breaking the social barrier and was able to get many people to give him money. Once he became a real flesh and blood person with eyes, a smile and needs, people gave in and opened their wallets. When the beggar left his new pupil, he felt so sorry for poor Daniel –and his panhandling ineptitude– that he actually gave him some money. Of course Daniel tried to refuse, but the beggar insisted.

I think there are two main lessons here. The first is to realize how much of our lives are structured by social norms. We do what we think is right, and if someone gives us a hand, there’s a good chance we will shake it, make eye contact, and act very differently than we would otherwise.

The second lesson is to confront the tendency to avert our eyes when we know that someone is in need. We realize that if we face the problem, we’ll feel compelled to do something about it, and so we avoid looking and thereby avoid the temptation to give in and help. We know that if we stop for a beggar on the street, we will have a very hard time refusing his plea for help, so we try hard to ignore the hardship in front of us: we want to see, hear, and speak no evil. And if we can pretend that it isn’t there, we can trick ourselves into believing –at least for that moment– that it doesn’t exist. The good news is that, while it is difficult to stop ignoring the sad things, if we actively chose to pay attention there is a good chance that we will take an action and help a person in need.

Better (and more) Social Bonuses

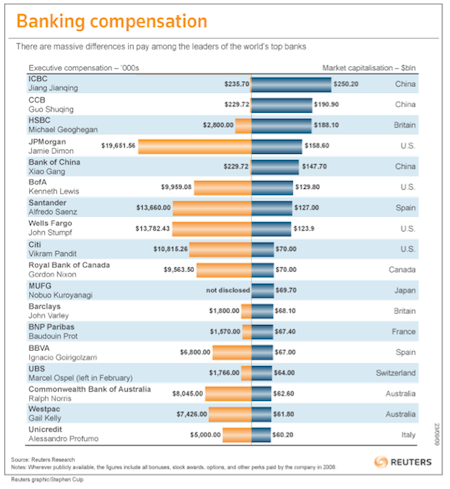

Over the last few years, many individuals (myself included) have been feeling tremendous anger about the level of executive compensation in the US, an anger that is particularly strong against those in the financial sector. As you can see in the chart below, there is an incredible gap between CEO compensation in the US compared to most other countries. Bankers are paying themselves exorbitant wads of cash, seen in both in their salaries and bonuses. And in their defense, the bankers in question claim that such extravagant wages are essential to properly motivate them, and that without such motivation they would just go and find a job somewhere else (they never exactly specify which jobs they will get and who will pay them more, but this is another matter).

Inordinate compensation levels aside, it is important to try and figure out more generally how payment translates into motivation and performance. There is a general assumption that more money is more motivating and that we can improve job performance by simply paying people more either in terms of a base salary, or even better as a performance-based incentive – which are of course bonuses. But, is this an efficient way to compensate people and drive them to be the best that they can be?

A new paper* by Mike Norton and his collaborators sheds a very interesting light on the ways that organizations should use money to motivate their employees, boost morale and improve performance – benefiting both employees and their organizations. The researchers looks at a few ways that money can be spent and how that affects outcomes such as employee wellbeing, job satisfaction and actual job performance. Specifically, they examine the effect of prosocial incentives, where people spend money on others rather than themselves, and they find that there are many benefits to spending money on others (think about the inherent joy of gift-giving).

In the first experiment, the researchers gave charity vouchers worth $25 or $50 to Australian bank employees and asked them to donate the money to a charity of their choice. Compared to people who did not receive the charity vouchers, those who donated $50 (but not $25) claimed to be happier and more satisfied with their jobs.

The second experiment took the concept of prosocial incentives a step further by directly comparing people who were asked to spend money on themselves (a personal incentive) with those who were asked to purchase a gift for a teammate (a prosocial incentive). This experiment took place in two different settings — with sales and sports teams — and looked at a broader range of outcomes. It not only examined employee satisfaction, but also the other side – benefits to the organization in terms of employee performance and return on investment. While neither sales nor sports teams improved when people were given money to spend on themselves, Norton and his colleagues found vast improvements for those who engaged in prosocial spending. While they were purchasing a gift for a teammate, they also became more interested in their teammate and were happier to help them further in multiple other ways.

If we compare these experiments, we can also see that while a gift of $25 did not make a difference when it was donated to a faceless and impersonal charity, a gift of $20 provided numerous positive outcomes when it was given in the form of helping out a teammate. Thus, it appears that we can reap the greatest benefits when we spend money on others, and even more when we spend money on close others.

Taken together, these results also suggest that our intuitions are leading us down the wrong path when we assume that we will be happiest and most motivated when we earn money to spend on ourselves. The findings from this paper can be extended to recommendations for current business practices, particularly in cases where compensation is very high. In fact, Credit Suisse has gotten a head start on adopting the idea of prosocial spending, as it has recently implemented a program requiring its employees to donate at least 2.5% of their bonuses to charity. Now, is this just a PR trick to try and diffuse some of the anger that people feel these days about bankers, or is this a real effort to increase and improve motivation? I don’t know. But what is clear to me is that prosocial incentives, either in the form of charitable donations or team expenditures, can be an effective means of encouraging more positive behavior for the individual, their teammate and for society.

* Norton MI, Anik L, Aknin LB, Dunn EW & Quoidbach J (manuscript under review). Prosocial Incentives Increase Employee Satisfaction and Team Performance.

Which Cities Are The Most Generous?

Recently I decided to come up with a rough measure of generosity across different communities. Which communities have a culture of giving away unused items as opposed to trying to sell them? And why?

One of the ideas was to use Craigslist as a rough measure. Looking at the 23 major cities on Craigslist, we took the number of free items being given away in one week and divided it by the number of items being sold in the furniture category, as a quick index of generosity. In a nutshell: for every 100 items of furniture being sold, how many items are being given away for free?

As you can see, Portland, SF Bay, Boston, and Seattle come up on top in terms of this measurement, with Miami, Phoenix, and Houston on the bottom.

Is this a good metric for measuring generosity across communities?

An Irrational Guide to Gifts

I have recently been asking people around me what they think makes a good gift. And I don’t mean specific items like sunglasses or one of my books (which are all excellent ideas); I was looking to find some of the basic principles and characteristics of good gifts. One of the best answers I’ve gotten so far is this: “A good gift is something that someone really wants, but feels guilty buying it for themselves.” What is interesting about this answer is that the ideal gift from this perspective is not about getting the person something that they can’t afford, or something that they have no idea that they want – it is all about alleviating guilt connected with the purchase of a highly desirable (yet guilt invoking) item. So, lets consider two ways in which good gifts can eliminate guilt:

Case 1* Imagine that you are walking by a storefront and you notice a beautiful coat that is just the right cut and color. You walk in to check it out, and up close it is even more beautiful. But then, you look at the price tag and you discover that it is about twice as expensive as you originally guessed, and after 30 seconds of painful deliberation you decide that you can’t possibly justify paying so much for a coat – and you go on your way. When you get home, you find out that your significant other has purchased that same exact coat for you … from your joint checking account. Now, ask yourself how you would feel about this. Would you say a) “Honey, this is very nice of you, but I have weighted the costs and benefits earlier and decided that this coat is not worth the money — so please take it back immediately” or b) “Thank you so much, I love it, and I love you!” I suspect that the answer is b. Why? Because by getting you the expensive coat, your significant other got you what you wanted without making you contemplate the guilt associated with the purchase.

Case 2** Imagine that you have just finished a fantastic meal and have the option to pay with cash or with a credit card. Which one will “hurt” a bit more? You probably think that paying with cash will be a more miserable way of spending your money – but why? Because, as Drazen Prelec and George Loewenstein show, when we couple payment with consumption, the result is a reduction in happiness. When we pay with a credit card the timing of the consumption of the food and the agony of the payment occur at different points in time, and this separation allows us to experience a higher level of enjoyment (at least until we get the bill).

To think some more about this example, imagine that I own a restaurant and I realize that on average people eat 50 bites and pay $50. One day you come to my restaurant and I tell you that because I like you so much I will give you a great price and charge you half price – only 50¢ per bite. In addition, I will also charge you only for the bites you eat, and you will not have to pay for the bits that you don’t eat. What I will do is serve you your food and stand next to you with my notebook open and mark in it each bite you take. At the end of the meal I will charge you 50¢ for every bite you took. I think you will agree that this would be a fantastically cheap meal relative to the regular price, but I also suspect you will agree that the process will not be much fun. Most likely, every time you take a bite you will be thinking “is this worth it?” and in the process not enjoy the meal at all. Woody Allen might have said it best in the Manhattan taxi ride when he turns to his date to say, “You look so beautiful, I can hardly keep my eyes on the meter.”

The lesson here is that when the timing of consumption and payment are close together, the experience ends up being much less pleasurable. From this perspective you can think about gift certificates for iTunes, drinks, movies, etc. as gifts that not only get people to experience something new, but also get them to experience something guilt-free, and without the pain of paying.

In summary, I think that the best gifts circumvent guilt in two key ways: by eliminating the guilt that accompanies extravagant purchases, and by reducing the guilt that comes from coupling payment with consumption. The best advice on gift-giving, therefore, is to get something that someone really wants but would feel guilty buying otherwise.

May this be a joyful gift-giving season – and in case you want to get me something, I love gadgets, but feel extremely guilty buying them.

Dan Ariely

A shorter version of this post has appeared at the WSJ

[* This example is based on a paper by Dick Thaler, “Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice,” Marketing Science, 1985]

[** This example is based on a paper by Drazen Prelec and George Loewenstein, “The Red and the Black: Mental Accounting of Savings and Debt,” Marketing Science, 17(1), 4-28, 1998]

Helping kids raise $

Here is a letter I got from Mary Kate Dilworth ….

Dear Dan,

Hello. My name is Mary Kate Dilworth, and I am a junior at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Alexandria, Virginia. Last summer, I read a copy of Predictably Irrational, and now it sits on my bedside table because I reference it so often in my life. I find the chapter on social v. market norms particularly applicable to my life (I am in several volunteer organizations that regularly do fundraising projects).

Today, for example, my school’s Russian Honors Society had an Election Day bake sale. In years past, various goods have had set prices, but this year we chose to make it donation-based. What a difference it made! When one woman bought a cupcake, she reached for a one dollar bill and asked about the price. When I told her there was no set price but donations-only, she put the one back in her wallet and pulled out a ten. Your suggestion to switch to social instead of market norms was a great one-thank you so much!

Sincerely,

Mary Kate Dilworth

————————————————————–

Dear Mary Kate,

This is great, and I am delighted that you are taking lessons from the book and implementing them.

Next time think about trying both versions and measuring more directly the difference. It would be interesting to know if the effect is driven by a few people who give much more, by many people who give a bit more, or perhaps by more people becoming interested in the bake sale (or maybe all of these).

And good luck in your next implementation.

Dan

The Psychology of Gift-Giving

Here it is again: holiday gift-giving season – the best win-win of the year for some, and a time to regret having so many relatives for others.

Whatever your gift philosophy, you may be thinking that you would be happier if you could just spend the money on yourself – but according to a three-part study by Elizabeth Dunn, Lara Aknin, and Michael Norton, givers can get more happiness than people who spend the money on themselves.

Liz, Lara and Mike approached the study from the perspective that happiness is less dependent on stable circumstances (income) and more on the day-to-day activities in which a person chooses to engage (gift-giving vs. personal purchases).

To that end, they surveyed a representative sample of 632 Americans on their spending choices and happiness levels and found that while the amount of personal spending (bills included) was unrelated to reported happiness, prosocial spending was associated with significantly higher happiness.

Next, they took a longitudinal approach to the topic: they gave out work bonuses to employees at a company and later checked who was happier – those who spent the money on themselves, or those who put it toward gifts or charity. Again they found that prosocial spending was the only significant predictor of happiness.

But because correlation doesn’t imply causation, they next took one more, experimental, look at the topic. Here, they randomly assigned participants to “you must spend the money on other people” and “spend the money on yourself” conditions — and gave them either $5 or $20 to spend by the day’s end. They then had participants rate their happiness levels both before and just after the experiment.

The results here were once more in favor of prosocial spending: though the amount of money ($5 vs $20) played no significant role on happiness, the type of spending did.

Surprised by the outcome? You’re not the only one: the researchers later asked other participants to predict the results and learned that 63% of them mistakenly thought that personal spending would bring more job than prosocial purchases.

Happy holidays

Dan

Why Bankers Would Rather Work for $0.00 Than $500K

Sometimes asking someone to do something for nothing is more powerful than paying them.

In a research paper entitled “Effort for Payment: A Tale of Two Markets,” James Heyman and I that people are willing to help move a couch or perform an experiment just by being asked. Moreover, these individuals feel good about their “gift”. Most interestingly, the experiments show that contrary to standard economic theory, paying a small incremental incentive does not increase effort, but actually lowers it — because meager compensation profanes the gift effect and disincents the giver.

Bringing money into the relationship takes the giver’s work out of “gift” market, and brings it into the “pay-for-effort” market. When it was done for nothing, the protagonist was a “donor.” When small money was on the table, he or she became an underpaid employee. The easiest way to think about this is to imagine if at the end of Thanksgiving dinner you asked your mother-in-law how much you owed her for cooking such a wonderful meal. Would that increase or decrease her effort the next time you came by? (Assuming, of course, she would still invite back you after such an insult.)

In this financial crisis, there has been much discussion about banker’s pay. We think that if President Obama had asked for a group of bankers to take $0, and paid expenses only, it would have brought the discussion back into the gift economy. $500,000 is just low enough to bruise the banker’s egos (after all, they got used to much higher salaries for a long time, higher salaries we can be pretty certain they feel they deserved), but $0 is something to be proud of! In fact, paying these CEOs nothing might remind them about the responsibility they have to the banks they are leading and to the rest of society. The CEO of AIG Ed Liddy is already only taking a one-dollar salary and donating his time to this worthy effort. But his gift is isolated, a drop in the bucket — not part of an overall “corps” of senior financial executives acting in unison to help fix the mess.

Would the best people be willing to work for free? Not all capable bankers could afford it, but many could. We think there would be many willing to pitch in…if asked in the right way. After all, this gift idea was at the core of John F. Kennedy’s brilliant notion, “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” By eliminating pay altogether, these leaders would be giving the nation the donation of their time and skill, improving their level of motivation. Instead of accusing them of being greedy and self interested, people could see them as important actors playing key roles in the stability of our entire economy. This in turn would probably encourage more bankers to see the power of a collective gift and the joy they could feel in donating something so important.

As it stands now, the many good people who are trying to improve things for little or no pay are isolated, their effort drowned out by the outrage over bonuses and salaries. Hence we have the Congress and President involved in legislating the level of executive compensation all the way down to its structure and timing! Congress should not be mired in the details of compensation design. Not only are they bad at it, but the beleaguered public — whose median household income is less than 1/10th of $500,000 — is watching the pay ping pong with collective disgust. The knee-jerk reaction to create a confiscatory 90% tax on the AIG bonuses makes the conservatives among us think we are killing capitalism itself.

When individuals commit acts of personal generosity, it sparks a gift culture that replenishes a store of trust — a resource as multiplicative as any Keynesian monetary policy. This sharing is not done in a communist, carving-up-the-spoils manner, but rather in the tradition of bravery and sacrifice for our collective benefit. When those in power act within a gift culture guided by a spirit of generosity for common cause, it creates a tangible trust asset that supports the flow of credit, money, and markets. By focusing on limiting executive pay, President Obama did the political equivalent of asking his mother-in-law how much he owed her for Thanksgiving dinner — and moved the discussion away from social responsibility, and into the pay-for-effort market, where the negotiations for spoils now dominate the discourse.

We think our bold young President has to improve his request. A gift culture — created at the top — will benefit all of us; and, strangely, will also help strengthen the rapacious markets where self-interest reigns supreme. The good news is, it’s not too late.

By John Sviokla and Dan Ariely

Gifts: Ridiculous or Useful?

From a standard economic perspective, gifts are a waste of money. Imagine that you invite me over for dinner one day and I decide to spend $50 on a bottle of wine. There are a bunch of problems: To start, I am not sure what wine you would like the most. And besides, maybe you’d prefer something else, like a book, a DVD, or a blender. This means that the bottle of wine that cost me $50 might be worth, at most, $25 to you. (more…)

10 year anniversary

Yesterday was Sumi’s (my lovely wife) and my 10 year wedding anniversary.

It took me a while to figure out what to do for this event and at the end I decided on two things: First, I booked us a night at the same bed & breakfast where we got married 10 years ago. This was a slightly risky move because there was a chance that the place will not be as wonderful or romantic as we remember, and this will spoil the wonderful memories we have from our wedding day. Luckily this was not the case, and the place was just as wonderful and romantic as we remembered. (more…)

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like