Can the tax code cause us to spend too much?

April 15th — Tax day is upon us, so it’s a perfect time to contemplate a few aspects of taxes.

In the past I’ve written about how I used to think that tax day was a wonderful day of civic engagement – a day to think about how much we make and contribute, what taxes we pay and what services we get in return. Of course, over the years, as my taxes have become more complex, this task becomes one that is less about civic engagement and thoughtfulness, and more about annoyance and frustration. But that’s for another time.

Today I want to talk about the fact that the US tax system makes it very difficult for us to understand how much money we make and how this may actually lead us to spend more money than we really have. Think about it for a moment—do you know your net monthly income? I suspect you don’t, and I think that the tax system is to blame.

In many other countries, the tax code does not allow for the same level of deductions we have, and because of that for most people the whole amount of taxes is automatically deducted from their paycheck – and this is it. Now, in this situation when you ask people how much they earn [and yes, in other countries people do actually ask each other what they make] they will tell you their net monthly income – the amount of money that they get to take home at the end of each month. How do they know? Well, it is the number that is printed in bold letters on their paystub.

Contrast this to the US. In the US, we all know the gross amount that we make a year, but it’s not as clear what our net income is. It’s actually very complex because we get our salary, some of which the employer withholds, and we have no idea what we’ll get back when tax day comes around. We can get back some money (depending on our expenses/deductibles), trends in our stock market portfolio, health care, etc. And we don’t figure this out until April 15th (if not later) of the following year!

And what are the consequences of knowing our gross yearly income and not much else? I think it causes us to feel richer than we really are and spend accordingly. Why would this be the case? There’s a phenomenon we call the “illusion of money,” which is the idea that we typically pay attention to nominal amounts of money rather than real amounts. For example, the illusion of money means that if inflation is 8%, and you get a 10% raise, you would feel better than if there was no inflation and you got a 3-4% raise. The basic idea is that we pay attention to the nominal amount rather than the purchasing power, and don’t realize what our money is really worth.

In terms of our tax code, this suggests that in the US we focus on our gross yearly income, feel richer than we really are, and consequently end up spending more money. If this is right, it means that changing the structure of deductions could be one way to help people understand how much money they actually have and how they can save more.

The Rationality of One-Star Reviews

When publisher Hachette Book Group set its price for Michael Connelly’s latest suspense thriller, The Fifth Witness, it decided to charge $14.99 for the Kindle version and $14.28 for the hardback version, a difference of $0.71.

From a utility point of view, charging more for the Kindle version seems quite reasonable considering that Kindle books are delivered instantly and for free, that they take up no additional space or weight, that they can be read on any computer, and that they come with handy bookmarks and highlights of what other readers find interesting.

But how did customers respond to this pricing decision? They were outraged! As you can see on the product page, the book has been overwhelmed with one-star reviews based not on the quality of the book itself but instead on the perception of greed and unfairness on behalf of the publisher. “junk,” writes Amazon reviewer Juan M. “It’s ridiculous that the E-BOOK is as much as the physical copy. Greed indeed.”

Talia S. puts it this way: “I went and check the reviews and notice the many 1 star grading. I read some of them and changed my mind. I did not buy the book. We should not let the publishers hold us hostage because we prefer to read the electronic format.”

While standard rational economics tells us that consumers will be willing to pay more for items they derive more utility (pleasure and usefulness) from — in practice, other factors such as perceived fairness and perceived manufacturing costs play a very large role into our decisions of what to buy and how much we are willing to pay.

As someone who has published two books, and purchased a lot of them over the years, I find books to be one of the most puzzling categories in terms of how much attention people pay to their price. Think about it this way — if you were going to spend 10 hours with a book, do you really care if it costs $3 more? Shouldn’t you happily pay $0.30 more per hour of reading if the quality of the book was slightly higher or the experience was slightly better? Personally my more pressing problem is time, and if someone could assure me a better, even slightly better experience, I would pay a substantial amount more. And for some books, those I really treasure and that have changed my view on life — if I were just thinking about the utility of my experience I would pay hundreds of dollars.

The problem is that it is really hard to think this way. It is not easy to focus on what we really care about (the quality of the time we spend) rather than the salient attribute of price. And on top of that the unfairness of the differences in price can make us mad ….

I don’t know how the book industry will deal with this problem, and I am looking forward to seeing how this story develops. But, I do know that as readers we should pay a little less attention to minor differences in price and more attention to the quality of the way we spend our time.

Irrationally yours

Dan

Gold

Negotiating at Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar

While recently in Istanbul I took the opportunity to study the city’s market system, trying my hand at some negotiating. What techniques have sellers developed to gain the upper hand against savvy buyers?

Negotiation@Grand Bazaar from serendipity on Vimeo.

Caught between

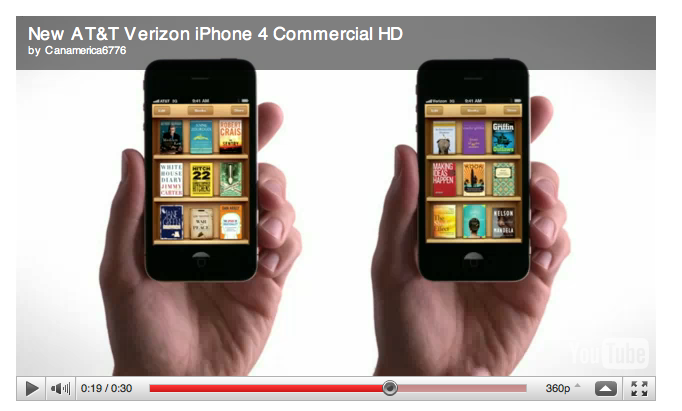

Although I’ve very clearly come down on one side of the debate about rationality in economics, there is another war that I’ve just found out I’m in the middle of. If you look very closely in the picture below from a recent iPhone commercial, Upside of Irrationality is one of the preferred books of the AT&T iPhone user!

While it’s nice that Apple put me in the middle of this war between AT&T and Verizon, In line with their slogan that “two is better than one”; what would have been really nice is to have both of my books featured–one on each shelf.

Rethinking Money for the New Year

In today’s economy, consumers and financial institutions alike are constantly on the lookout for new ways to reduce spending. As you read this article, consider these questions: what cost-cutting habits has your organization developed, and are they rational? Do you recognize irrational or habitual spending tendencies in your own customers and members? If so, how can you help them make better decisions that lead to improved savings?

Money is an integral part of modern life. We constantly make decisions about whether we’re willing to pay for different products and, if so, how much we are willing to pay. In fact, we make decisions about money so often that we consider money to be a natural part of our environment.

However, money is a relatively recent invention, and despite its incredible economic usefulness it does come with its own set of problems. In particular, it turns out that decisions about money are often unintuitive and, in fact, quite difficult. Consider the following situation as an example: you are thirsty, tired, and annoyed and just want a cup of coffee. You see two coffee shops across the street from each other. One is a specialty coffee shop that sells handcrafted, designer coffee and the other is Dunkin’ Donuts, which sells standard, decent coffee. The price difference between the two options is $1.75 for your cup-a-joe. Now, how do you decide if the benefit of the handcrafted coffee drink is worth the additional $1.75?

What you should do (if you wanted to be rational about it) is consider all of the things that you could buy with that $1.75, now as well as in the future, and decide to buy the expensive coffee only if the difference between the two coffees is more valuable than all of those other possibilities.

But of course this computation would take hours, it is incredibly complex, and who even knows all the possible options to consider?

Heuristically Speaking

So what do we do when we need to make decisions but making them “correctly” is too time-consuming and difficult? We adopt simplifying rules, which academics call heuristics, and these heuristics provide us with actionable outcomes that might not be ideal but that help us to reach a decision. One of the heuristics we often use is to look at our own past behaviors, and if we find evidence of relevant past decisions, we simply repeat those.

In the case of coffee, for example, you might search your memory for other instances in which you visited regular or fancy coffee shops. Then you might assess which behavior is more frequent, and tell yourself, “If I’ve done Action X more than Action Y in the past, this must mean that I prefer Action X to Action Y” and as a consequence, you make your decision.

The strategy of looking at our past behaviors and repeating them might seem at first glance to be very reasonable. However, it suffers from at least two potential problems. First, it can turn a few mediocre decisions into a long-term habit. For example, after we have gone to a fancy coffee shop three times in a row and paid a premium for the same coffee we could get elsewhere, we might continue with this strategy for a long time without reconsidering how much we are really willing to pay for coffee.

The second downfall is that when market conditions change, we are unlikely to revise our strategy. For example, if the price difference between the regular and fancy coffee used to be $0.25 and over the years has increased to $1.75, we might stay with our original decision even though the conditions that supported it are no longer applicable.

Examine old habits

In light of our current financial situation, many people these days are looking for places to cut financial spending. Once we understand how we use habits as a way to simplify our financial decision making, we can also look more effectively into ways to save money.

If we assume that our past decisions have always been sensible and reasonable then we should not scrutinize our long-term habits. After all, if we’ve done something for five years, it must be a great decision. But if we understand that long-term, repeated behaviors might reflect our habitual decision making in the face of complex financial decisions more than they reflect what is truly best for us, we might first examine our old habits and carefully consider whether they indeed make sense or not. We can examine our subscription to the ESPN Sports Package, our annual subscription to the opera, our yearly Disneyland vacation, or our monthly visit to the hairstylist.

By examining these habits — and quitting them when it makes sense to do so — we might actually discover ways in which we could reduce our spending on a long-term basis.

Yes, money is complex, and it is incredibly difficult for us to carefully examine (and re-examine) every purchasing decision we make. But the advantage of examining our habits is that it might lead us to create better ones that will benefit us for a long time.

May you have a happy and exciting new year,

Dan

This column first appeared at http://www.deluxeknowledgeexchange.com

Locksmiths

I recently had an interesting meeting with a locksmith:

As I mention in the video, what’s really interesting is that this locksmith was penalized for getting better at his profession. He was tipped better when he was an apprentice and it took him longer to pick a lock, even though he would often break the lock! Now that it takes him only a moment, his customers complain that he is overcharging and they don’t tip him. What this reveals is that consumers don’t value goods and services solely by their utility, benefit from the service, but also a sense of fairness relating to how much effort was exerted.

Now imagine how much more people would pay if they knew the effort that goes into all kinds of products and services?

Black pearls

How do we decide how much we are willing to pay for things?

Let’s take black pearls as an example:

The interesting thing about black pearls is that when they were first introduced to the market there was essentially no way to gauge how much they were worth: were they worth more or less than white pearls? Most people instinctually believed that white pearls were still more desirable. But then the black pearl discoverers had an lucrative insight: take these unfamiliar black pearls to a famous jeweler and have them displayed next to the more precious gems: rubies, sapphires, and so on. The result still lives with us today: black pearls are now worth more than white pearls.

An Irrational Guide to Gifts

I have recently been asking people around me what they think makes a good gift. And I don’t mean specific items like sunglasses or one of my books (which are all excellent ideas); I was looking to find some of the basic principles and characteristics of good gifts. One of the best answers I’ve gotten so far is this: “A good gift is something that someone really wants, but feels guilty buying it for themselves.” What is interesting about this answer is that the ideal gift from this perspective is not about getting the person something that they can’t afford, or something that they have no idea that they want – it is all about alleviating guilt connected with the purchase of a highly desirable (yet guilt invoking) item. So, lets consider two ways in which good gifts can eliminate guilt:

Case 1* Imagine that you are walking by a storefront and you notice a beautiful coat that is just the right cut and color. You walk in to check it out, and up close it is even more beautiful. But then, you look at the price tag and you discover that it is about twice as expensive as you originally guessed, and after 30 seconds of painful deliberation you decide that you can’t possibly justify paying so much for a coat – and you go on your way. When you get home, you find out that your significant other has purchased that same exact coat for you … from your joint checking account. Now, ask yourself how you would feel about this. Would you say a) “Honey, this is very nice of you, but I have weighted the costs and benefits earlier and decided that this coat is not worth the money — so please take it back immediately” or b) “Thank you so much, I love it, and I love you!” I suspect that the answer is b. Why? Because by getting you the expensive coat, your significant other got you what you wanted without making you contemplate the guilt associated with the purchase.

Case 2** Imagine that you have just finished a fantastic meal and have the option to pay with cash or with a credit card. Which one will “hurt” a bit more? You probably think that paying with cash will be a more miserable way of spending your money – but why? Because, as Drazen Prelec and George Loewenstein show, when we couple payment with consumption, the result is a reduction in happiness. When we pay with a credit card the timing of the consumption of the food and the agony of the payment occur at different points in time, and this separation allows us to experience a higher level of enjoyment (at least until we get the bill).

To think some more about this example, imagine that I own a restaurant and I realize that on average people eat 50 bites and pay $50. One day you come to my restaurant and I tell you that because I like you so much I will give you a great price and charge you half price – only 50¢ per bite. In addition, I will also charge you only for the bites you eat, and you will not have to pay for the bits that you don’t eat. What I will do is serve you your food and stand next to you with my notebook open and mark in it each bite you take. At the end of the meal I will charge you 50¢ for every bite you took. I think you will agree that this would be a fantastically cheap meal relative to the regular price, but I also suspect you will agree that the process will not be much fun. Most likely, every time you take a bite you will be thinking “is this worth it?” and in the process not enjoy the meal at all. Woody Allen might have said it best in the Manhattan taxi ride when he turns to his date to say, “You look so beautiful, I can hardly keep my eyes on the meter.”

The lesson here is that when the timing of consumption and payment are close together, the experience ends up being much less pleasurable. From this perspective you can think about gift certificates for iTunes, drinks, movies, etc. as gifts that not only get people to experience something new, but also get them to experience something guilt-free, and without the pain of paying.

In summary, I think that the best gifts circumvent guilt in two key ways: by eliminating the guilt that accompanies extravagant purchases, and by reducing the guilt that comes from coupling payment with consumption. The best advice on gift-giving, therefore, is to get something that someone really wants but would feel guilty buying otherwise.

May this be a joyful gift-giving season – and in case you want to get me something, I love gadgets, but feel extremely guilty buying them.

Dan Ariely

A shorter version of this post has appeared at the WSJ

[* This example is based on a paper by Dick Thaler, “Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice,” Marketing Science, 1985]

[** This example is based on a paper by Drazen Prelec and George Loewenstein, “The Red and the Black: Mental Accounting of Savings and Debt,” Marketing Science, 17(1), 4-28, 1998]

Gray Areas in Accounting

Every profession is bound by written and unwritten rules and policies; some of them are set by organizations while others are an integral part of the occupation you choose. For example, doctors have to swear by the Hippocratic Oath, lawyers cannot divulge any privileged attorney-client conversations, and priests cannot reveal what was said to them in the confessional. The same kind of ethical code exists in the profession of accountancy because it is a means of public service. As Robert H. Montgomery put it, “Accountants and the accountancy profession exist as a means of public service; the distinction which separates a profession from a mere means of livelihood is that the profession is accountable to standards of the public interest, and beyond the compensation paid by clients.”

However, accountants are plagued by deep ethical dilemmas – there may be times when their employers ask them to twist and tweak the financial position of the company because they’ve had a bad year. The usual spiel given is that they’re definitely going to rake in the profits in the months that follow and that the deficits that have been covered up this year will more than be taken care of in the years to come. So the accountant is left wondering if he/she should be loyal to their professional ethics or show loyalty to the company that has hired them.

To overcome this type of problems, ethics is taught as a subject when you choose to study accountancy, because you are responsible not just to your employer, but also to the general public who believe in your reports and statements and take important decisions based on your word. An important question here if course is how effective are ethics classes, and even if they are successful how long would their influence last (a week? a month? a year? 2 years?). It is hard to believe that taking one or two classes on ethnics while studying accountancy is going to have a long term effect, and most likely higher standards and more strict definitions of continuing are needed (and maybe also higher frequency of education).

In other cases accountants are torn between reporting misbehaviors that are going on and between minding their own business – should they open up a can of worms and be at the center of a controversy or just take heart in the fact that they were true to the ethics of their profession? This type of cases present the “action inaction bias” where in general people view their own actions as much more important than inactions – which means that accountants are more likely to care about their own actions than about reporting the actions of others. Yet, accountants must remember that they are accountable for not just their actions, but also their non-actions, if either tend to affect the public adversely.

Overall the study of accountancy, and understanding its challenges is not only important in its own right, but it also provide an important case from which to view problems of conflicts of interest

By-line:

This guest post is contributed by Omar Adams, he writes on the topic of online accounting degrees . He welcomes your comments at his email id: omaradams47@gmail.com.

Tweet

Tweet  Like

Like